The White House can’t fathom why President Joe Biden is polling so poorly on the economy.

America’s macroeconomic indicators look pretty strong. Unemployment is still low at 3.9 percent. Consumer price inflation has come down to just over 3 percent. Grocery prices are no longer rising overall. So why is consumer sentiment weaker than in the depths of the pandemic (see Figure 1)? And why is Biden trailing former President Donald Trump by 20 percentage points on who would better handle the economy?

Some Democrats had consoled themselves that sentiment is a lagging indicator. The public is still angry that their grocery bills have gone up 21 percent in three years, having only risen by 18 percent in the previous 11. But give it eight more months of rising real pay and falling inflation and that sentiment will turn, or so the party hoped. Indeed, as Figure 1 shows above, sentiment has improved significantly since November 2023. Perhaps that’s a precursor for an improving polling performance.

Larry Summer’s new paper provides a more uncomfortable explanation for voters’ angst. American consumer sentiment is lower-than-expected, he and coauthors conclude, because of higher interest rates driving higher costs of new mortgages, car finance, and credit card purchases. This is worrying for Democrats, because interest rates are unlikely to fall as dramatically by the time of November’s election.

What Summers’ paper gets at is the distinction between “inflation” and the “cost of living,” which I touch on in my forthcoming book, The War on Prices. When economists worry about inflation, they mean the rise in the general level of prices, or a decline in the purchasing power of a money unit. When the public worries about inflation, they tend to think about their living costs. And that includes the cost of borrowing. “Consumers, unlike modern economists, consider the cost of money [i.e. interest rates] part of their cost of living,” as the paper puts it.

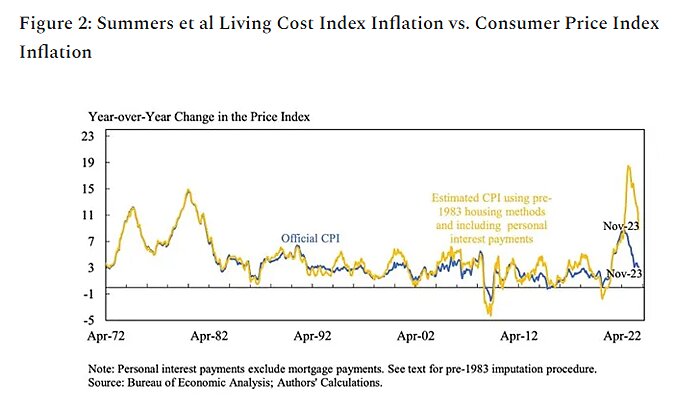

Official “inflation” indices seek to estimate changes in the general level of prices by tracking a basket of goods that consumers tend to buy. As such, these official price indices don’t factor in certain household costs that go up due to higher interest rates. New car loan interest payments, for example, have nearly doubled in America since 2021. Interest payments on a new 30-year mortgage have tripled. Summers and co therefore devise an alternative cost-of-living index that measures housing costs as they were accounted for before 1983, and also includes personal interest payments for cars and credit cards, to test whether these factors account for Americans being down on the economy.

In the “great moderation” from the early 1980s, unemployment and inflation did a reasonable job in explaining economic sentiment. Today, there’s a sharp disconnect between these macroeconomic metrics and sentiment. Modest inflation and low unemployment predict that the University of Michigan’s consumer sentiment index should today be above its 86.5 average since 1979. Instead, it’s lagging at 79 (and 69.7 when the paper was written).

Summers and co suggest that the sharp growth of interest payments for new mortgages and fewer banks making consumer installment loans accounts for most of the difference. Almost a third of Americans say it’s a bad time to buy a car because interest rates are high (the highest negative sentiment ever) and around two-thirds say it’s a bad time to buy a house for the same reason (the highest since 1982).

Applying the relationship between consumer sentiment and their new index from the pre-pandemic period to afterwards allows them to estimate that more than 70 percent of America’s unexpected pessimism can be explained by higher interest rates. Indeed, look at Figure 2: by their new metric the recent spike in living costs is worse than anything seen in the 1970s.

Is this the final word on why voters are miserable about the economy? Surely not. There does appear to be a high degree of partisanship on economic sentiment. And there are not many people paying 7 percent rates on their mortgage, after all.

Yet it’s surely the case that the interest costs of marginal loans are affecting voters’ perceptions about the economy. Some people are paying higher rates, others will be forgoing loans because of high rates. Even people not directly affected will know others giving up the dream of home or car ownership because of interest rates, or see people struggling with rolling over debts.

Summers’ paper shouldn’t be interpreted as saying that improving macroeconomic fundamentals aren’t helping Biden, or that the way economists measure inflation now is “wrong.” It’s still plausible that Biden will get a big polling bounce if inflation keeps falling, and especially if the Fed starts easing up on interest rates significantly before the election.

The key point is: Democrats thought that the economic fundamentals were solid for Biden and, if only people understood them, they would help him secure victory. If Summers is right and it turns out the White House is just ignoring a fundamental that voters care highly about – the sharp rise in interest rates — then November could be very painful for the President.