Among the more frustrating parts of my job are the seemingly endless proposals for government intervention in the economy on the thinnest of “market failure” grounds. Whether it’s trade or manufacturing or housing or child care or the environment, our virtual pages are full of claims that a perceived problem—Rents are too high! We don’t make enough EVs!—is clearly the fault of unfettered market forces and, by extension, thus in need of new (usually “smart” or “targeted”) government intervention that will improve the situation. As economist Maxwell Tabarrok put it earlier this year, “market failure” in econ classes and public policy “is never taught without using it to study and justify government intervention in markets, implicitly or explicitly defining the government as a ‘social welfare maximizer.’” Once you realize this omission, you see it everywhere—including in this brand new think piece in the New York Times on how a Harris administration would magically solve the nation’s economic problems.

As we discussed at length several years ago, a common flaw in such assertions is that problems in a particular market have been caused not by unbridled capitalism and a lack of government intervention but by other forces, often other government policies. In the case of U.S. Steel, I explained back then, the company had benefited from decades of government support—protectionism, subsidies, bailouts, regulatory exemptions, procurement mandates, etc.—and, far from being a claimed market failure, its recent abandonment of a Pennsylvania steel mill project was “precisely what the economics literature anticipates” from a sputtering, state-sponsored oligopolist. Dig through past editions of Capitolism and you’ll find many other examples of fake “market failures” justifying even more government intervention. As The Atlantic’s Jerusalem Demsas and others have pointed out, that NYT piece was similarly misguided:

But perhaps the best example of this mistake is baby formula, which interventionist types bizarrely keep citing as a market failure when anyone actually examining the issue—including the uber-interventionist Federal Trade Commission and this brand new report from the National Academy of Sciences—acknowledges that pervasive government regulation both contributed greatly to the supply chain crisis of 2022 and thwarted the U.S. market’s recovery.

(Toldja.)

As Compared to What?

There is, however, another big, lesser-discussed flaw in the market failure thesis: Even when a real market failure has been identified, we can’t assume that a chosen government fix will actually be effective—or, in fact, an improvement over the admittedly suboptimal market situation. And several recent examples show just how big a problem this is, across multiple fronts.

First, the government fix might be poorly designed. Consider, for example, a landmark new study of 1,500 climate-related policies implemented by 41 countries between 1998 and 2022, which found that only 63 of them—a piddling 4.2 percent!—successfully reduced greenhouse gas emissions. (Researchers used AI to find 69 episodes of rapid and significant emissions reductions but could connect those breaks to only 63 national policies.) As the Wall Street Journal helpfully summarized, one big reason for the lack of success is that policymakers have relied on the wrong policy mix:

Subsidies and regulations—policy types often favored by governments—rarely worked to reduce emissions, the study found, unless they were combined with price-based strategies aimed at changing consumer and corporate behavior. …

In 2015, more than 190 nations signed the Paris agreement, pledging to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius above preindustrial levels to avoid the worst effects of climate change. As part of the treaty, nations are required to document how they will achieve emissions reductions. By searching through the OECD database, which identifies 46 types of policy interventions, the study’s authors found government policymakers prefer subsidies and regulations, according to [study co-author Nicolas Koch].

“We see a lot of policy packages built around these two policy types, and we find that it’s very rare that they really work in reducing emissions,” Koch said. The study found the nations’ overall climate emissions will exceed the Paris target by 23 billion metric tons of CO2 by 2030.

In the United States, the authors found just one successful emissions reduction intervention, in the transportation sector. Everything else we’ve done did little to nothing—at least not quickly. And, it should be noted, the Inflation Reduction Act and related U.S. EV policy also heavily leans on subsidies and regulations, while carbon pricing and/or taxes remain unused.

Second, government fixes can be (and often are) poorly implemented. Here, popular state price gouging laws—supposedly needed to stop big businesses with market power from hurting helpless consumers during emergencies—provide a good and timely case study. As economist Michael Giberson reviewed over the weekend, even if you assume these laws have a sound theoretical basis (you shouldn’t), their implementation strays a long way from the supposed intent. Some of them, for example, don’t precisely define “gouging” and instead “use vague prohibitions against unconscionable price increases and leave it to judges to decide whether a price increase was, in retrospect, too much.” And they often apply in times other than declared emergencies: In New York, the law is triggered by “abnormal disruptions of the market,” but in practice this means judges ultimately decide when disruptions begin and end.

Thus, you have cases in which one judge says a company is guilty/innocent and then another disagrees on appeal. And New York businesses can “only guess” whether they’re breaking the law—an outcome that’s not merely unfair but also will have inevitable economic harms (e.g., businesses simply closing down during emergencies to avoid running afoul of the law).

Giberson also reviews how New York’s enforcement of its price gouging law is also a problem, as it’s “almost entirely devoted to penalizing small businesses,” like hardware stores, motorcycle dealers, independent gasoline stations, and convenience stores—not big corporations. In one terrible example, the state sued a small hardware store in Chazy, New York, that had only one generator in stock when an ice storm knocked the region’s power out, bought 54 generators from other states, sent a truck to get pick them up (“increasing supply” in an area that really needed it!), and sold them at higher prices to cover their costs. The kicker: “The judge commended the hardware store for its community service, but said the law compelled a judgment against it.” In other examples, the state (see, e.g., this case in Tennessee) uses the threat of lengthy litigation to force small retailers into settling and paying fines, just “to avoid the time and expense associated with litigation.”

Giberson covers other examples here, and economist Peter Klein has even more. As Giberson put it, “The question isn’t whether ‘markets are not working well’ but rather whether additional government involvement can reasonably be expected to work better than the way things are going without them.” And time and again, anti-gouging laws make things worse.

Some implementation failures, on the other hand, are less about selective or nauseating enforcement and more about plain ol’ bureaucratic incompetence:

To pick a particular example that people would be able to Google, there was a Free Application for Federal Student Aid—FAFSA. It’s a United States institution that is involved in helping people pay for college. There was a particular procedure that needed to get done for the FAFSA where there was an edge case and they said, “ah, for this edge case, you need to write into a help center for FAFSA and then the help center will make a determination and tell you how to proceed”—and 70,000 emails ended up in an inbox that went to nowhere and stuck there for a year and no one noticed that they weren’t getting the emails because the inbox was to nobody.

As AEI’s Brent Orrell noted earlier this year, U.S. broadband and charging station subsidies could be headed the same unfortunate way.

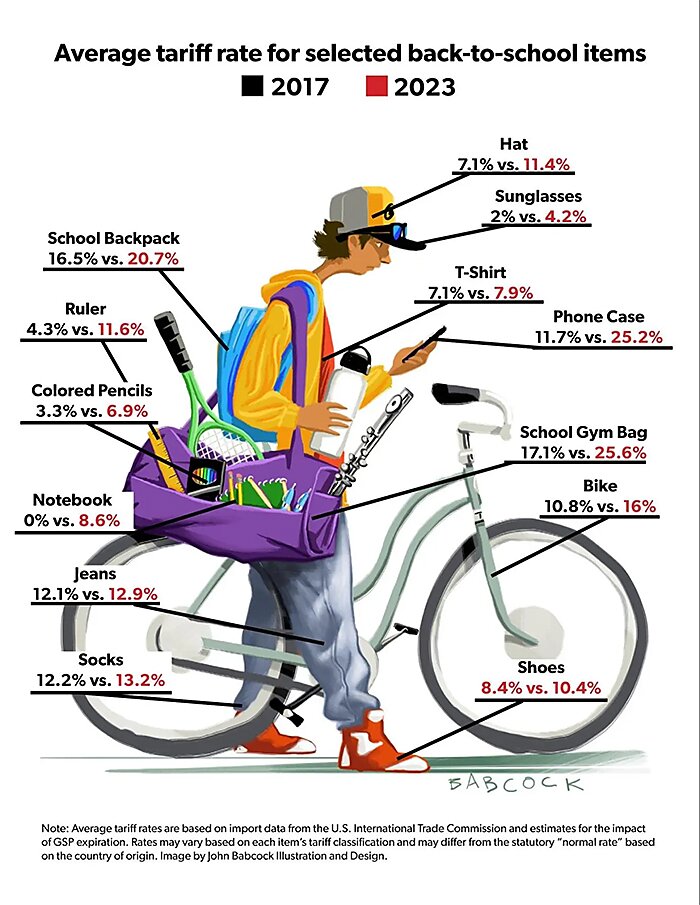

Third, government fixes to alleged market problems are often distorted by politics, and here again baby formula gives us an unfortunate example—a very unfortunate example. As noted above (and in previous editions of Capitolism), it was quickly evident when the supply crisis hit in 2022 that several regulatory impediments—tariffs, FDA regulations, and welfare programs—not only set the stage for the crisis, but also impeded market adjustment and recovery when the disaster struck. The White House, to its credit, quickly began exploring ways to relieve some of these regulatory burdens, including by issuing a presidential proclamation in mid-May that would temporarily waive U.S. tariffs on formula (which average around 25 percent). As ProPublica just reported, however, internal emails reveal that officials in the Office of the United States Trade Representative—yes, the office supposedly tasked with expanding U.S. trade—was cool to the plan (emphasis mine):

With supplies of baby formula falling precipitously across the country after a major production plant shut down, staffers from the USTR repeatedly argued against lifting the tariff on imports, citing, in part, a concern that it would raise “lots of questions from domestic dairy producers,” according to documents obtained by ProPublica. Cow’s milk is a primary ingredient for most baby formula, and the dairy industry has long supported protections for U.S. manufacturers.

USTR officials also suggested that U.S. dairy groups, which have long benefited from protectionism and are well mobilized politically, be given a “heads-up” before any tariff-related press release went out, “so that they don’t feel blindsided.” And they were upset with colleagues at the Department of Health and Human Services who “appeared to be criticizing the formula tariffs in conversations with congressional leaders.” (Heaven forbid!) It was only months later that Congress finally suspended formula tariffs through the end of the year.

Given all the other regulations (including FDA import barriers) at play here, it’s admittedly unclear just how much an earlier tariff suspension would’ve helped the U.S. market recover in mid-2022, but for our purposes that’s beside the point. Instead, the situation shows that government regulators—even in a legitimate crisis affecting some of the most sympathetic Americans there are!—are human and part of an organization that is inherently political, as opposed to some idealized “social welfare maximizer” (see Tabarrok again for more). As a result, government officials will draft and implement almost any economic regulation with an eye toward not just the economics and law, but the politics, too. And whether it’s baby formula or foreign investment or space exploration or energy or groceries, any other number of issues in which “the market” has supposedly failed, politics often wins out.

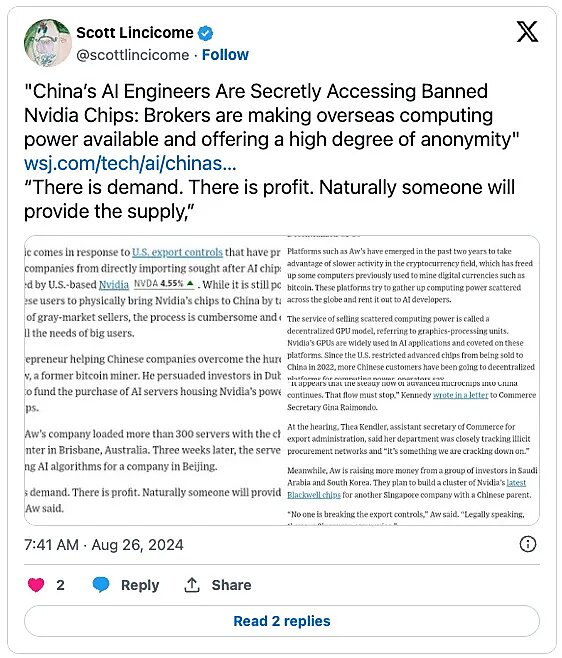

Finally, government fixes can have substantial unintended consequences that result in even bigger problems than the ones the regulation was designed to solve. New research shows, for example, that clean energy subsidies can actually increase emissions, while new U.S. subsidies might be crowding out other, better technologies that aren’t eligible. Or consider current U.S. restrictions on high-end semiconductor products to China, which the Trump administration started and the Biden administration amplified to prevent Beijing from achieving the technological frontier in both chips and other “strategic” technologies like artificial intelligence. Given the connection between China’s tech and military sectors and Western companies’ strong financial incentives to sell to China, restrictions make superficial sense. However, they also came with big costs—not only kneecapping American tech companies (including some “strategic” ones we’re now subsidizing) but also encouraging the government and Chinese chipmakers to focus on lower-end “legacy” chips that are less advanced but still used in many products (e.g., cars and appliances).

Today, even amid clear signs of China having too much capacity in this segment of the chip market, Chinese companies have been adding even more—and U.S. policymakers are freaking out about it, most recently applying new 50 percent tariffs to Chinese legacy chips to stave off additional financial problems for (subsidized) U.S.-based chipmakers.

The problem here, however, is that semiconductors are inputs into other manufactured goods, including ones the federal government has also deemed “strategic,” like EVs or even AI. Thus, the high U.S. tariffs might protect American chipmakers from import competition (competition fueled at least in part by U.S. sanctions!), but they’ll also put American automakers and other chip-consuming manufacturers at a competitive disadvantage vis-à-vis both Chinese and other foreign manufacturers—companies that can and will buy loads of cheap, tariff-free chips from China and, in the case of non-China companies, freely export their finished goods to the United States. Such competition could, in turn, push “strategic” American manufacturers offshore—similar to what happened to American PC companies in the 1990s when the U.S. slapped tariffs on Japanese semiconductors. In that case, domestic chip and computer prices were higher, and “the computer manufacturing industry shed one job for every U.S. semiconductor job supposedly gained” from the tariffs.

Thus, as Fortune recently concluded, “China is poised to dominate the market for legacy chips, and the U.S. may only have itself to blame.” Perhaps those unintended consequences would be worth it if U.S. export controls were truly thwarting China’s semiconductor and AI ambitions, but news reports indicate that chipmakers—while still behind the frontier—and AI researchers are catching up and they and other companies are finding creative ways to circumvent U.S. controls:

Thus far, at least, it seems we’ve ordered up a lot of pain for little gain.

Summing It All Up

Government solutions to “market failures” face their own set of challenges—in design, implementation, and effect—that can not only fail to achieve market-beating objectives but actually make things worse than if nothing had been done at all.

This reality doesn’t mean we should never address legitimate market failures with government regulation. Those failures can and do exist, with pollution being the most common example. But that alone doesn’t automatically warrant any and all government action. Instead, we must consider not just whether government should do something but whether it can and will implement a regulatory solution that beats the admittedly suboptimal outcomes the market is providing—and implement it in the real world, not on a computer screen or something some random country once pulled off decades ago in a global economy that no longer exists. As the examples above show, the answer is often “no, it can’t/won’t,” and that reality argues for fewer and better-designed regulatory actions (e.g., narrow ones with more transparency and less subjectivity), more humility about the government’s ability to pull off “moonshot” successes in non-moonshot times, and—yes—more tolerance for the messy, frustrating results that less-regulated markets produce. All too often, the cure is worse than the disease.

Chart of the Week

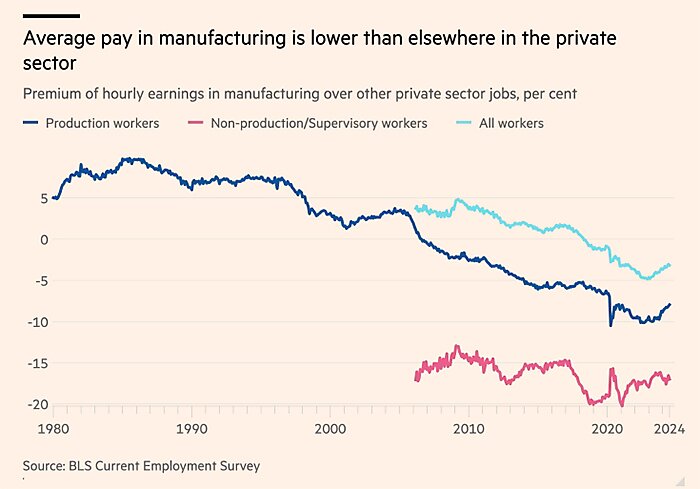

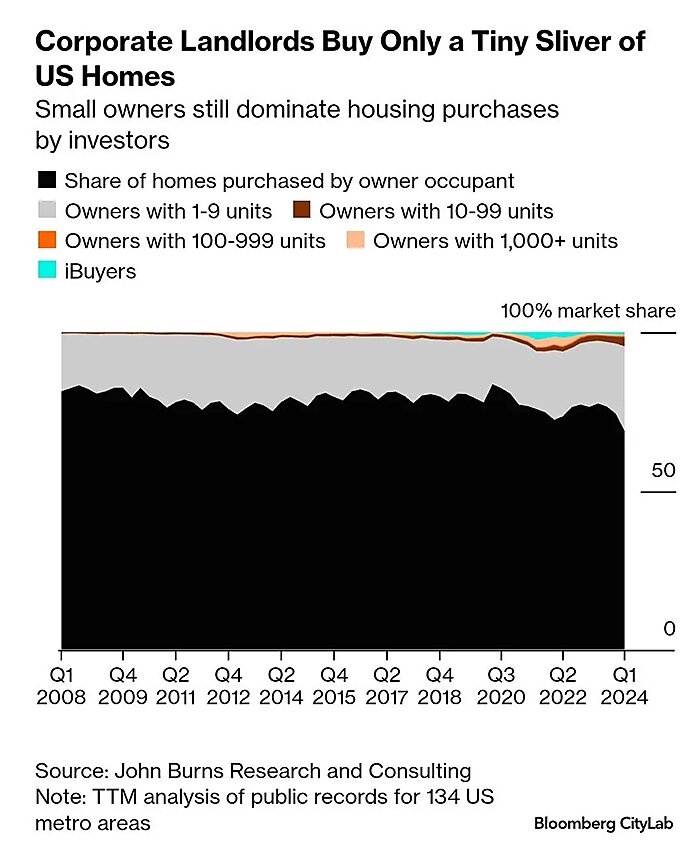

Manufacturing job myths (more)