Dear Capitolisters,

What’s Conservative about the New Conservatism?

Many conservatives have defended the new law as not only lawful and smart “red meat” politics, but also an exercise in good policy because it eliminated “corporate welfare.”

As I’ve mentioned here before, I hail from the right side of the libertarian spectrum and have long worked with conservatives, center-right media, and Republican politicians on various policy issues. Back then, we’d surely disagree on specific line items—Iraq or the drug war, for example—but we always shared a core belief in certain fundamental principles about government, public policy, and life. These principles, not necessarily shared by the left (for better or worse), ensured that we’d remain close allies in the political arena, regardless of our disagreements on discrete issues. (I even recall one time scoffing at a former colleague’s “liberaltarian” project in the early 2000s, because the left and libertarians had far more fundamental disagreements about natural rights, limited government, the rule of law, and related issues.)

As readers of The Dispatch are surely aware, this “fusionist” alliance has, in recent years, frayed, with many self-identified conservatives today accusing us libertarians of not only being turtleneck-wearing, election-losing chart jockeys but actually causing many of the right’s (and America’s) problems. But I think the Florida-Disney saga—particularly many mainstream conservatives’ reactions thereto—may take the schism to a whole new (and bad) level and reveal in the process that, if this is the “new conservatism” it’s not very “conservative” at all.

Before we get to that, however, let’s quickly go over the basic facts. As summarized in yesterday’s Morning Dispatch and elsewhere, shortly after Florida passed its controversial “parental rights” (aka “Don’t Say Gay”) education law, Disney bowed to internal and external pressure and announced in late March that it opposed the law and would lobby for its repeal. Almost immediately thereafter, Florida Republicans announced their intention to reexamine the “special district” encompassing Disney World—the Reedy Creek Improvement District (RCID)—that’s been in place since the theme park broke ground in 1967. A few weeks after that, Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis, whom most politicos believe is prepping a 2024 presidential run, instructed Florida’s legislature to expand its special session to consider the “termination of all special districts that were enacted in Florida prior to 1968,” including (coincidentally!) the RCID and five other, less significant districts: Bradford County Development Authority; Sunshine Water Control District (Broward County); Eastpoint Water and Sewer District (Franklin County); Hamilton County Development Authority; and the Marion County Law Library. Florida’s “special district” law passed the legislature and was signed by DeSantis a few days later. It will take effect on June 1, 2023, unless renegotiated before then.

Is This Conservative Policy?

Many conservatives have defended the new law as not only lawful and smart “red meat” politics, but also an exercise in good policy because it eliminated “corporate welfare.” Now, look, I bow to no man in my disdain for American corporatism (as longtime Capitolism readers surely know by now) and I defer to the experts on the state law and politics, but that policy part is a stretch, to put it kindly. First, as Charles Cooke explains at National Review, the RCID was created pursuant to a general Florida law allowing for special districts in unique circumstances, and Disney World is undeniably unique:

Walt Disney World’s setup in Florida is, indeed, unusual, but it doesn’t quite make sense to call it a “carve-out.” Properly understood, a “carve-out” is a rule that is applied differently to entities of a similar or identical nature: The Walt Disney Company, for example, enjoys a brazen carve-out in Florida’s tech-regulation bill: an exemption for Disney+ that was not granted to Netflix, Hulu, or HBO Max. By contrast, the rules that apply to Walt Disney World could be better described as “tailored,” for, despite the insinuations of many Florida Republicans, Walt Disney World’s accommodation is unique not in its type but only in its particulars. As it happens, Florida has 1,844 special districts, of which 1,288 are, like Walt Disney World, “independent.” The Villages — where Governor DeSantis made his announcement about the review of Walt Disney World’s status — is “independent,” as are Orlando International Airport and the Daytona International Speedway. Clearly, Walt Disney World is a weird place: It is the size of San Francisco, it straddles two counties (Orange and Osceola), and, by necessity, it relies on an infrastructure cache that has been custom-built to its peculiar needs. To claim that the laws that enable this oddity to work represent a “special break” is akin to claiming that the laws that facilitate special installations such as Cape Canaveral or the World Trade Center are “special breaks”: true, in the narrowest sense, but false when examined more closely.

Overall, there are around 38,000 of these “special districts” nationwide.

As indicated at the link above, there is a legitimate policy argument for reforming these districts (though I’m not sure I necessarily agree), but the RCID is hardly an example of the system’s drawbacks or corporatist abuse. As reported by NBC News and many others, the RCID has surely benefited Disney in some ways, but it’s also benefited surrounding areas and the state of Florida more broadly—a lot. In general, this is how it works: Disney gets to avoid many of the problems associated with local bureaucracy (permitting, infrastructure, debt, etc.) and gets to keep ugly or competitive businesses away from its pristine Florida compound—a key problem that Walt Disney wanted to avoid after such entities popped up all around Disneyland in California (thus making the RCID a key motivator for Disney’s location decision in the ‘60s). The RCID—and, by extension, Disney World—also gets some benefits in debt markets, as the area’s “municipal” bonds are untaxed and backed by Disney’s stellar credit, and Disney/RCID benefits from certain “free” municipal services (e.g., police) that the district doesn’t provide itself.

The RCID does, however, provide and fund many other services—water, fire, roads, etc. This is a big win for local governments, as they get to avoid the massive hassle of servicing a sprawling theme park (which was originally a swamp in the middle of nowhere). And, of course, they get all the economic activity that Disney World generates—activity that numerous studies have found to be massive. The district also appears to be a wash on the fiscal side, as native Orlandoan Sarah Rumpf explains:

Disney collects and remits sales taxes to the state (including the small percentage that goes to each county), as well as collecting Tourist Development Taxes from hotel guests, and Disney pays county property taxes (nearl y $300 million from 2015 to 2020) as well as RCID levying taxes on Disney’s properties to cover needed expenditures for local government type functions like building permitting, fire and emergency medical services, a power plant, water and waste treatment, trash and recycling, and construction and maintenance of roadways and waterways. RCID demands a higher standard than the neighboring counties, resulting in immaculately maintained roadways (locals frequently joke about trying to get Disney to seize control of the unending I‑4 construction), building codes that are state-of-the-art for hurricane protection, and significant resources devoted to environmental protection.

Your TMD crew notes that Disney does save millions on certain county building fees, but—again—that’s because the RCID handles such things and does so incredibly well: “Reedy Creek is probably the most efficient local government in Florida, because it’s not a typical bureaucracy. It’s run like a business.” Overall, the setup is—as Disney expert Rick Foglesong told the TMD—exactly “how those special taxing districts are supposed to work: Instead of relying on general taxation to produce public services that benefit everyone, you can use these taxing districts to raise money from yourself and to produce the kind of public services that are precisely tailored to what you need.” Or, as a local real estate lawyer told NBC, “Disney pays its way when it comes to government services. … It pays the two counties, and two county school boards — and gets very little services in return. It doesn’t get any exemptions there.”

Regardless of what one thinks about “company towns” in general, this company town seems to be doing pretty darn well, especially from a fiscally conservative (lower taxes, less bureaucracy, etc.) perspective.

Given these facts, some—including Orange County’s tax collector—have speculated that eliminating the special district might actually cost Florida taxpayers money if localities have to assume the RCID’s debt obligations or raise taxes to service the sprawling RCID area. However, it’s probably more accurate at this stage to simply say that nobody really knows. Open questions include not only what do with RCID’s $1 billion-plus in outstanding debt, which the counties would assume (if said reassignment is even legal), but also whether new county tax revenues (from entities that used to pay the RCID) would cover the district’s annual $100 million-plus operating budget. (The RCID can levy higher taxes than other Florida jurisdictions but runs an annual deficit of a few million dollars.) As one analysis put it, “Without a thorough audit of Reedy Creek’s financials, it’s impossible to say how much of what Disney is paying to the district could be collected by the counties.” And, per yesterday’s TMD, the DeSantis administration seems to agree (“I will let you know [about the fiscal impact] when we have more to share regarding the specifics of the plan.”)

So here we have an arrangement implemented pursuant to a generally applicable law, which allows a private entity to govern itself and in so governing (really, really well) provides clear practical and economic (and maybe even fiscal) benefits to the surrounding jurisdictions. That is hardly “corporate welfare” in any traditional sense (see, e.g., my old paper on subsidies for a generally accepted definition), and eliminating it—Disney/DeSantis battle aside—might leave almost everyone, including local taxpayers and RCID bondholders, worse off.

Furthermore, the anti-corporatist spin here rings especially hollow when you consider that similar self-governing districts in Florida (e.g., The Villages and other retirement communities) are untouched, that tens of millions in other, actual subsidies (e.g., tax breaks for corporate relocations or theme park travel packages) remain in place, that—as Cooke notes—Florida lawmakers “showed zero interest” in nixing the RCID whey they had the opportunity to do so in 2012, 2002, 1992, 1982, or 1972, and that Florida lawmakers seem uninterested in broader, systemic reforms (e.g., school choice) that would achieve undeniably conservative ends without all of the economic, legal, and other concerns.

So spare me the policy stuff, okay?

Are These ‘Conservative’ Principles?

If this were just about a narrow policy fight in Florida (over a law that might never even be implemented), I probably wouldn’t have even written about it. But, given the online discourse and DeSantis’ political aspirations, it sure seems like it’s about more than just the RCID or even “corporate welfare” more broadly—it’s about the direction of modern conservatism and the Republican Party away from numerous core principles that, until quite recently at least, most conservatives held (and shared with us libertarians).

First, the Florida law further erodes the longstanding distinctions between state action and private action, and between state power and corporate power. As I explained last year, regardless of however “big” some corporations may be (and some are certainly big), “the populist view of corporate bigness ignores the true and unique power of the state” to impose violence upon private individuals consistent with—and authorized by—domestic law. As a result, states big and small can, and routinely do, use or threaten violence to deny people and companies of their freedoms, their homes, their businesses, or even their lives. Google, Apple, and Disney can do a lot of stuff, but they can’t do that.

This distinction, however, seems lost in conservatives’ fight with Disney, which was routinely treated as equal to (or somehow even more powerful) than the state of Florida—an unaccountable global behemoth able to corrupt minds and change law. Ironically, as National Review’s Jason Lee Stoerts explained last week, the new Florida law shows quite clearly that, for however powerful Disney is, it ain’t government:

The rightist-populist attitude toward corporations has tended to blur the distinction between cultural pressure and formal state power; corporations are seen as quasi–state actors requiring a state response. But this episode puts the lie to that conflation. So — in a much more spectacular form — does the Chinese Communist Party’s persecution of Jack Ma. There is a hard distinction between formal legal power and even very strong forms of economic influence or cultural pressure. Private associations, even the wealthiest and most influential, can be destroyed in a day if the makers of the law decide to destroy them. When we endorse the idea that the state may take retaliatory measures against individual or collective actors whose speech it dislikes, we start down an intellectual road whose end point is tyranny.

That Disney can get singled out and punished in Florida of all places shows that preeminence of state power remains fully intact—no matter how much many of today’s conservatives try to deny it.

Second, the Florida law shows blatant disregard for fundamental rights, in this case political expression. As David French explained in The Atlantic, “[t]he First Amendment affirmatively protects the right of private institutions to engage in political speech, and that protection extends to safeguarding them from government reprisal for their speech”—a principle not only upheld by the courts but also strongly defended by conservative Republicans until very, very recently. In this case, however, there is little doubt that the law is intended to retaliate against Disney’s political speech and to discourage future public expression by Disney or by any other corporation that dares to defy Republican policy. According to the sponsor of the Florida legislation, for example, Gov. DeSantis expanded the legislature’s special session for one reason and one reason only:

BREAKING: Disney is a guest in Florida. Today, we remind them. @GovDeSantis just expanded the Special Session so I could file HB3C which eliminates Reedy Creek Improvement District, a 50 yr-old special statute that makes Disney to exempt from laws faced by regular Floridians.

— Rep. Randy Fine (@VoteRandyFine) April 19, 2022

DeSantis himself said as much after signing the law, singling out Disney’s lobbying efforts. And, in case there was any doubt left, Florida’s lieutenant governor not only said back in March that Disney had “no right to criticize legislation by duly elected legislators” (and that she and DeSantis “won’t stand for it”), but also went back on TV after the bill passed to agree with her host that Disney could get its special status back … if it changed its position.

Other movement conservatives have been similarly unsubtle about the law’s effect on future (“woke”) political speech that they don’t like. A few indicative quotes:

And these aren’t even the Natcons! Anyway, the law’s message to the rest of us is similarly clear: fundamental rights are disposable when politics or the culture war demand it.

Third, the law—particularly the timeline laid out above and the lack of any serious efforts to nix the RCID before Disney spoke out—makes a mockery of the “rule of law” that conservatives once (rightly) held so dear. As Steorts explains (emphasis mine):

Florida is far from Russia or China or Iran or North Korea. But there is a precise equivalence as to the temporal sequences. First, those who made the law had obvious personal interests. Second, they made laws that served those interests. Whenever and wherever this happens, to whatever degree, great or small, it is no longer clear that the law restrains lawmakers’ self-interested whims rather than being determined by those whims.

That is what puts the “Gangster” in “Gangster Government.” It is also what makes the consequences Phil [Klein] warns of, should they come, objectionable. Any citizen justly prosecuted for murder, any corporation justly prosecuted for fraud, has in a certain sense become an enemy of the state. But for the state to declare its private-sector enemies in advance and then endow itself with means of punishing them destroys the guarantee of impartiality and disinterest that we wanted to get from the rule of law in the first place.

Indeed.

Finally, we are left to question conservatives’ longstanding support for a limited government of enumerated powers—support based on the aforementioned principles, as well as proven concerns about the corrupting influence of government power, narrow laws’ frequent expansion (“creep”) into other areas, or the obvious threat of turnabout actions when political adversaries take power (as they always do). Here, again, the Florida kerfuffle is instructive. For one thing, the law undermines speculation that, the new right might return to its principled roots after achieving political power by any means necessary: As Cooke notes in the piece linked above, “Governor DeSantis has already fought Disney, and he has already won”; subsequent political action is salting the earth.

Similarly telling is the common conservative defense of the Florida law—that “the left” has been using government power to smite conservative enemies of the state for years now. But progressives, by definition, harbor far fewer ideological reservations about using the state in (ahem)novel and heretofore-constitutionally-suspect ways to achieve “urgent” priorities, real or imagined. Fears of government power or respect for longstanding fundamental rights are supposed to prevent conservatives from doing the same.

Or, at least, they were.

To be perfectly clear, certainly not all of my former fellow travelers have (at least momentarily) abandoned these principles. Indeed, several folks linked above are still card-carrying members of Conservative Inc. And, yes, this is only one episode—one perhaps cynically pushed by politicians who knew the courts—or a subsequent renegotiation—would ensure that this punishment never actually happened. Nevertheless, the speed with which many of the right’s keyboard warriors ditched their principles is breathtaking. And it’s further proof of, as Matthew Continetti details over at Commentary, the American right’s decades-long evolution from a principled, intellectual, incremental movement to an aggressive and radicalized one steeped in “religion, nationalism, and populism”—the Trumpian id supplanting the Reaganite ego.

The right’s division here, per Klein, is significant but in his view “more tactical than ideological”: the old guard “see[s] conservatism as a set of clear and timeless principles that should be consistently adhered to, regardless of whether they lead to preferred short-term outcomes in every circumstance,” while the other side “may be sympathetic to many of the same principles, but they believe that any principle that gets in the way of achieving their preferred outcomes should be discarded without remorse.”

But jettisoning all of these principles to smite political enemies is ideological, and obviously so. It’s why, as Continetti quotes (repeatedly), the most committed—and honest—members of the New Right are clear that their path to power involves “shed[ding] conservatism altogether.”

Will their new conservative allies do the same?

Chart(s) of the Week

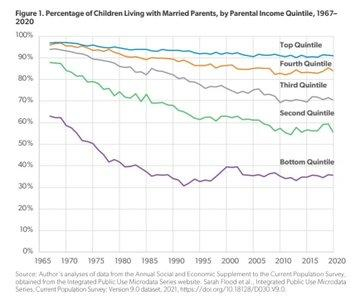

“A Half-Century Decline in Marriage… That Ended 30 Years Ago for Disadvantaged Kids”

The Links

Me, on Biden’s protectionism and skyrocketing construction costs

The long history of free trade

Why Covid Did Not Spell the End of Globalisation

Land rush: Rust Belt towns turning into e‑commerce hubs

Those Texas truck inspections appear to have been a very costly political stunt

America’s top labor markets aren’t in big cities

Community input is Bad, actually

“Covid Lockdowns Revive the Ghosts of a Planned Economy”

Furman, Sumner mind-meld on inflation and NGDP targeting

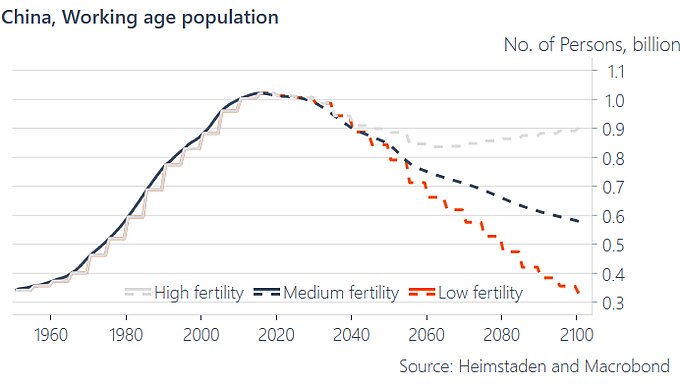

“Foreign investors are ditching China. Russia’s war is the latest trigger” https://cnn.com/2022/04/25/investing/china-capital-outflows-covid-ukraine-war-intl-mic-hnk/index.html

China can’t (or won’t) quit the Dollar-led global financial order

Uber, but for global logistics

Amazon’s effect on the American workplace

Public schools and the culture wars