Dear Capitolisters,

Later today, I’ll have the privilege of testifying before the Senate Judiciary Committee’s Subcommittee on Competition Policy, Antitrust, and Consumer Rights on the topic of “Baby Formula and Beyond: The Impact of Consolidation on Families and Consumers.” Antitrust and baby formula are issues we’ve discussed here (repeatedly), but not in the same column. So I'm sharing with you today a lightly edited (now with charts!) version of my opening statement below. Some of this will definitely sound familiar to avid readers, but I nevertheless hope you all enjoy it.

Chair Klobuchar, Ranking Member Lee, and distinguished Senators:

Thank you for inviting me to testify today. My name is Scott Lincicome, and I am the director of general economics and trade at the Cato Institute, where I work on various economic issues, including international trade, subsidies and industrial policy, manufacturing and global supply chains, competition, and economic dynamism.

Today, I will discuss the current problems in the U.S. infant formula market and how we got here, with particular emphasis on market concentration and antitrust policy. As has been widely reported, the domestic infant formula market is concentrated and stagnant: prior to this year, two domestic brands accounted for almost 80 percent of U.S. formula sales, and there had not been a single new manufacturer registered with the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 15 years. This has undoubtedly contributed to the current crisis: when the largest U.S. formula producer, Abbott Laboratories, initiated a voluntary recall and shut down a major factory in Michigan, there were no easy or immediate replacements to fill a gaping hole in the U.S. market. We’ve been scrambling ever since.

This troubling situation, however, does not justify new U.S. antitrust actions or expanded government powers to police anticompetitive practices in the United States. The main justification for antitrust action has traditionally been the existence of a “market failure”—natural imperfections in a relatively free, private marketplace, involving things like time lags, search or startup costs, information asymmetries, or other factors, that give a monopoly or oligopoly market power to keep prices elevated or competitors out. As the Supreme Court wrote in 1992, “The purpose of the [Sherman] Act is not to protect businesses from the working of the market; it is to protect the public from the failure of the market.” In such cases, so the theory goes, government intervention in the market is needed to correct for the failure and restore consumer-friendly competition.

In the case of infant formula, however, today’s producer concentration and any resulting problems therefrom are primarily the result of federal government policy, not any sort of natural, private market failure. In particular, U.S. policies in both the international and domestic market work together to all-but-ensure that the infant formula market here is stagnant and dominated by a small handful of large, domestic corporations.

U.S. Trade Barriers Fuel Market Concentration

First, federal policies effectively block almost all foreign-made infant formula from the U.S. market—contributing to market concentration. For starters, the United States maintains high tariff barriers to formula from major producing regions, such as the European Union. Imports are subject to a complex system of tariff rate quotas, under which tariffs from 14.9 percent to 17.5 percent increase even further once certain quantity thresholds are met, and further again in some cases. The United States also restricts imports of formula from most “free trade” agreement partners, including major dairy producing nations like Canada and Australia. In fact, a key provision of the U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA)—supported by trade associations representing American dairy farmers and formula producers—tightened restrictions on Canadian baby formula to discourage additional investment there.

Overall, the Congressional Research Service estimates that less than 20 percent of the small amount of infant formula imported between 2012 and 2021 entered the United States duty-free, while the remainder faced an average effective calculated duty rate of 25.1 percent.

The United States also imposes significant non‐tariff barriers on all imports of infant formula. Most notable are strict FDA labeling and nutritional standards that any formula producer wishing to sell here must meet. Aspiring manufacturers also must register with the agency at least 90 days in advance and undergo an initial FDA inspection and then annual inspections thereafter. And the FDA maintains a long “Red List” of non‐compliant products that are subject to immediate detention upon arriving on our shores, including formula made by two of the most popular European brands among American consumers—HiPP and Holle—which arrive here only via unofficial, third-party channels. Despite strong domestic demand for these and other formulas—formulas all approved by unquestionably competent regulators abroad—shipments have been routinely seized and destroyed by U.S. Customs and Border Patrol because they did not comply with FDA labeling and other rules.

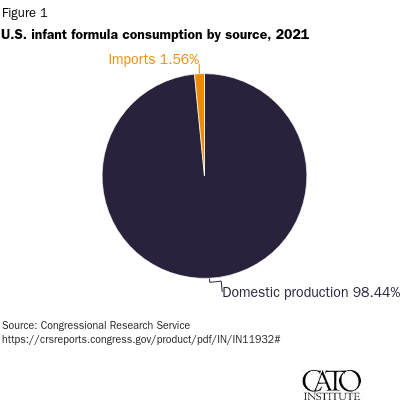

As a result of these tariff and non-tariff barriers, the U.S. market is dominated by domestic producers: the White House estimates, for example, that 98 percent of the U.S. infant formula market is annually serviced by domestic production, while the CRS calculates even smaller import shares in 2021 and previous years. Formula’s domestic share of the market is among the highest of any major food product.

These high walls around the United States in turn fuel concentration in the American infant formula market. According to a recent study from economists at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, for example, import competition serves as a significant check on the market power and domestic concentration of large U.S. manufacturers across a wide range of industries. In fact, they find that concentration falls in most industries that experienced high growth in import penetration between 1992 and 2012, while “the industries with low initial import penetration continued to have a low share of foreign firms, and showed the largest growth in market concentration.”

Such findings are obviously relevant for a concentrated U.S. infant formula market with essentially no imports (until, of course, President Biden ordered them airlifted here to ease current shortages).

U.S. Welfare and Regulatory Policy Exacerbate Market Concentration

Next, federal government policy exacerbates domestic market concentration and restricts market entry in two key ways. Most importantly, the expansion and design of a U.S. food assistance program, the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children (“WIC”), effectively ensures that the U.S. market remains dominated by a handful of large producers. WIC provides vouchers for low‐income Americans to buy pre-determined brands of formula at approved retailers for discounted prices. Since the program’s inception in 1974, WIC participation has grown dramatically from around a hundred thousand participants in 1974 to more than 6.2 million in 2021. Today, WIC is the dominant buyer of infant formula in the U.S. market, estimated to account for more than half of all domestic sales each year.

This buying power allows the government to demand that producers bid against each other and offer steep discounts—on average, 92 percent below wholesale value. To induce producers to participate, state WIC agencies since 1989 have offered sole-source contracts to winning bidders, giving them additional shelf space at participating retailers and greater credibility in the state at issue.

This system undoubtedly saves U.S. taxpayer dollars, but—when combined with WIC’s sheer size—creates serious problems in terms of market concentration and competition. For starters, only large, established producers have the production capacity, capital, and regulatory expertise to navigate the WIC contracting process across numerous states and to offer steep, up-front discounts on large-volume government contracts. Indeed, the three largest producers in the United States hold all state, territory, and tribe WIC contracts, and the largest producer—Abbott—was awarded 49 of them (including 34 of 50 state WIC contracts) for 2022. Smaller players simply cannot play on WIC’s field.

Furthermore, WIC’s exclusive contracts help winning bidders gain market share and raise prices in the non-WIC market—effectively becoming the dominant supplier in the state at issue. Research shows, in fact, that a WIC-winning manufacturer’s market share increases by an average of 84 percent after securing a WIC contract, due to increased sales of WIC-eligible and non-WIC eligible formula. In California, a 2007 WIC contract change from Abbott to Mead Johnson caused the former’s market share to drop from 90 percent to 5 percent, while the latter’s share did just the opposite—rising from 5 percent to 95 percent.

In sum, the size and design of the WIC program has greatly contributed to the U.S. market being served almost entirely by a few large companies. As one industry expert recently told the Wall Street Journal, “If the government doesn’t change [the WIC] system, things will go back to the way they were—a forced duopoly. It might take a year or two years or three years, but it will happen.”

Finally, stringent FDA regulations specific to infant formula are also likely amplifying domestic market concentration. Ever since Congress passed the Infant Formula Act of 1980, the United States has tightly regulated the contents and manufacture of infant formula—regulations that Congress tightened even further in 1986. As a result, infant formula is regulated more strictly than other foods in the United States and more strictly than formula in most other countries.

Regardless of whether one believes this level of regulation to be justified, it likely contributes to concentration in the infant formula market. Recent research finds, for example, that increases in industry-specific regulation are associated with statistically significant decreases in the number of firms in a market, and that higher regulatory growth rates are associated with lower startup rates and other indicia of economic dynamism. Put simply, more regulation means more concentration.

Anecdotal evidence supports these findings for the highly regulated infant formula market. Until a few weeks ago, there had not been a new formula manufacturer in the United States since 2007, and it took the new player, ByHeart, more than $190 million and five years “to get its manufacturing facility opened, supply chain in place, clinical trial completed and regulatory approval secured.” The company’s CEO told the Journal this week that “he understands why more new brands haven’t tried to break into the industry”—in particular, “We spent years trying to study and understand FDA regulations.” The CEO of Bobbie—another startup that relies on an existing U.S. manufacturer—said much the same, noting that “the market remains largely impenetrable to newcomers.”

The FDA also has reportedly struggled with a backlog of submissions for new formulas and delayed final approvals. The agency’s 2021 budget estimates that it reviewed only 22 of 31 applications received last year, with the final outcome in each case unclear. Such delays are an additional barrier to entry.

What to Do

The U.S. infant formula market is indeed concentrated, and this situation has surely contributed to the current crisis—exacerbating product shortages and preventing quick market adjustment in response to economic shocks. However, these problems are not the natural result of a relatively free market in desperate need of new antitrust regulation. Instead, they have been caused in no small part by government policies that restricted competition from abroad, bolstered the dominance of a handful of large domestic corporations, and stifled new market entrants. Policymakers looking to improve the U.S. infant formula market should therefore reform these policies, not add another layer of government regulation atop the numerous ones we already have. Reforms could include:

-

Eliminating all tariffs and tariff rate quotas on imported infant formula;

-

Revising the USMCA to allow for the free movement of infant formula between the United States, Canada, and Mexico;

-

Requiring the FDA to permit the importation, marketing, and domestic sale of any infant formula approved by a competent regulator abroad, such as those in Australia, Canada, the European Union, the European Economic Area, Japan, New Zealand, and Switzerland;

-

Reducing the size (and thus influence) of the WIC program, while also eliminating the sole source contracting model so that participants may purchase any infant formula lawfully sold in the U.S. market; and

-

Streamlining the FDA approval process for new market entrants and reconsidering whether Congress has struck the proper balance between public health and market competition under the Infant Formula Act of 1980 and its amendments.

Creating a freer market for baby formula will not immediately resolve the current crisis, but doing so would ensure that our domestic market is more competitive and more resilient when the next crisis hits.

Thank you, and I look forward to answering your questions.