Dear Capitolisters,

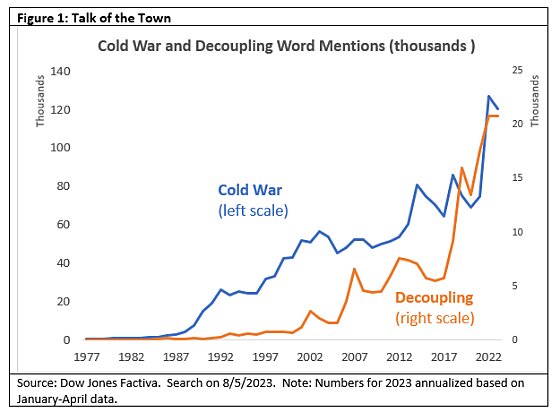

One of the trendier topics among econ journalists and wonks these days is the “decoupling” of the U.S. and Chinese economies. Seemingly not a day goes by without someone citing the heated political rhetoric, the confrontational policy moves (tariffs, export controls, sanctions, etc.), and recent changes in bilateral trade flows to argue that we’re witnessing “the end of multilateralism” (or whatever) and a return to the pre-World War II system of fragmented trade and regional trading blocs. Others go even further, arguing that we’re now in a “New Cold War” (or whatever), that hawkish Biden administration policy is actually too dovish, or that only a complete decoupling of the two economies—fueled by high tariffs, investment restrictions, and other government barriers—is needed both to safeguard national security and ensure U.S. economic dominance in the decades ahead. The news hits have predictably skyrocketed:

Yet, as popular as the decoupling narrative is, many such discussions suffer from a troubling lack of nuance about both the current state of bilateral trade and investmentandwhat the data actually show—and, by extension, the real-world implications of a “hard decoupling” of the U.S. and Chinese economies.

Our ‘Soft Decoupling’ Reality

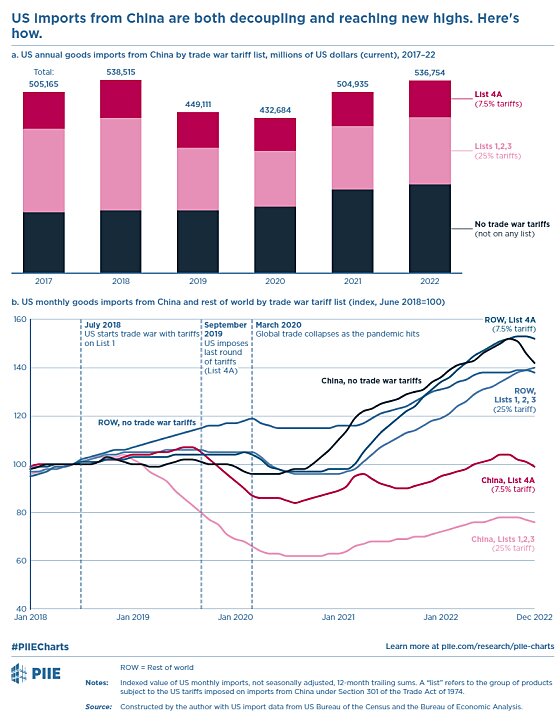

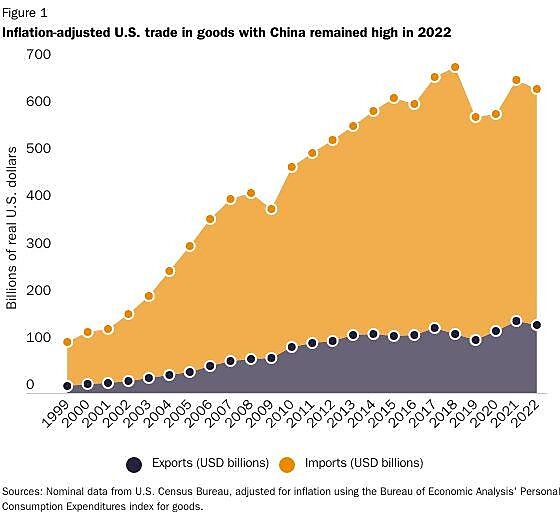

Despite all the tariffs and the heated rhetoric, there’s been little real sign of a major break from the pre-Trump status quo—at least so far. Most notably, trade in goods targeted by U.S. and Chinese policy measures has declined, but that’s been accompanied by an increase in trade in other goods and services that haven’t been caught up in the trade war:

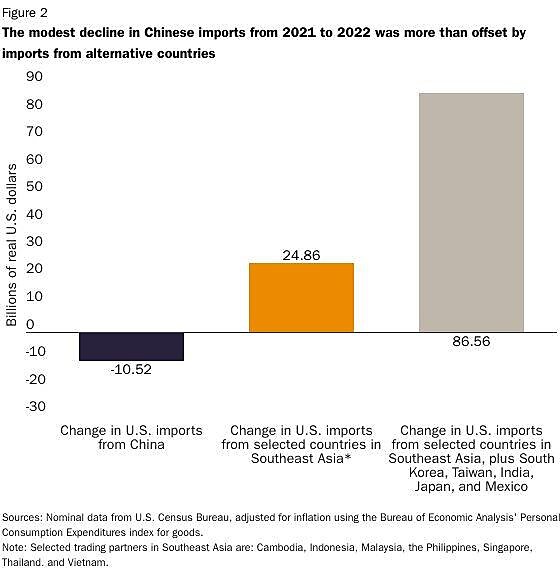

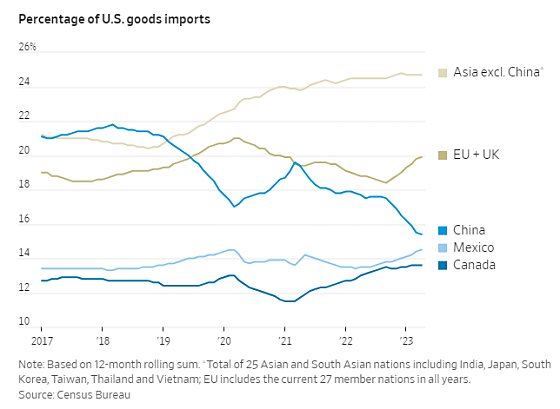

Meanwhile, U.S. trade with the rest of the world—particularly Mexico and other China “surrogates” in Asia—increased even faster than trade with China last year:

This is not a major decoupling, nor is it—as we’ve discussed—strong evidence of a fundamental U.S. retreat from the global economy, despite all the protectionist rhetoric and policy coming from the Trump and Biden administrations. That stuff is bad, of course, but it’s not “deglobalization.”

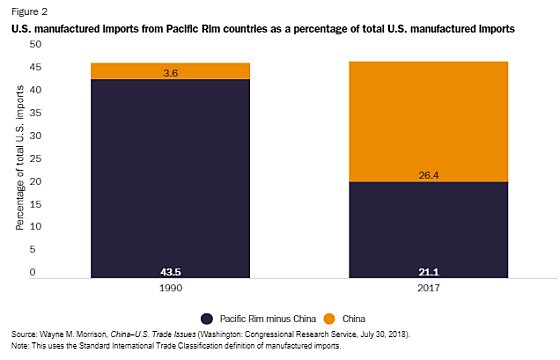

(As an aside, it’s useful to note here that the chart above basically shows a reversal of what happened during the 1990s and 2000s when Chinese imports displaced imports from other Asia-Pacific economies. Combined with lackluster U.S. manufacturing data, the trend serves as more evidence that Chinese manufacturers—contra the widespread “China Shock” narrative—compete with Asia-Pacific producers in the U.S. market as much or (probably) more than they do with American ones, though surely there’s some direct competition there too. But I digress.)

The general takeaways from these data are that some U.S‑China “decoupling” is indeed happening at the margins and that the bilateral relationship certainly isn’t expanding like it did two decades ago, but there’s little recent sign of a new and sudden “hard decoupling” (so far, at least).

‘Made in Not-China’ (Sorta)

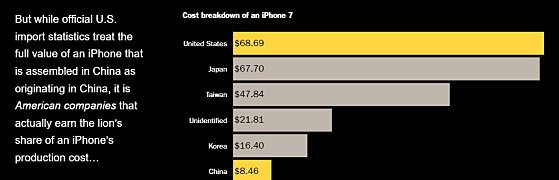

Just as important, if not moreso, is the rarely mentioned fact that the trade data are probably underestimating—by a significant amount—the extent to which U.S.-China goods trade remains intertwined. That’s because all the usual data simplistically assign imports’ and exports’ total (gross) value to a single country, when in reality most of these products—thanks to the proliferation of global supply chains—contain value-added from other countries, including the United States and China. Thus, for example, the full value of an imported automobile will show up in standard trade stats as coming from Japan, even though it has parts from numerous other countries. The “made in China” iPhone 7 reflects the same issues:;

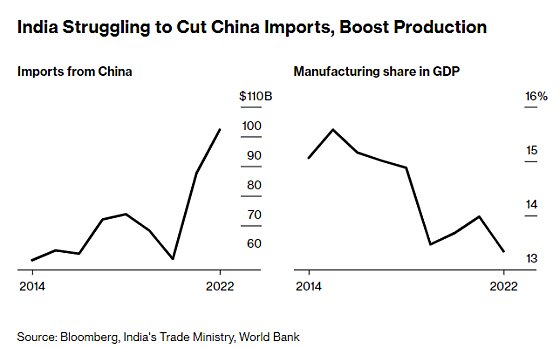

Trade economists have grappled with the gross-versus-value-added distinction for years now, but it takes on added significance in any discussion of U.S.-China “decoupling” because of China’s sheer size and Chinese manufacturers’ participation in so many Asia-Pacific manufacturing supply chains. Thus, for example, we read about how India and Vietnam are replacing China as both a destination for manufacturing investment and a platform for exporting to the United States, but such stories usually ignore that both of these countries are also receiving investment and inputs from companies that still have operations in China. Thus, Bloomberg reports, Indian manufacturers have found themselves in a “Catch-22 … the more they try to ramp up production in competition with China, the more dependent they become on their northern neighbor for components and raw materials.”

As Vietnam develops, it remains highly dependent on ties to China’s crucible of manufacturing around the Pearl River delta, which— marketing material from Deep C at Haiphong points out— is just “12 trucking hours” away.

That proximity allows for easy transfer of materials but leaves Vietnam’s supply chain more vulnerable, according to Brian Lee Shun Rong, an economist at Maybank in Singapore. “What happens if there are any disruptions to the flow of imports from China?” he said.

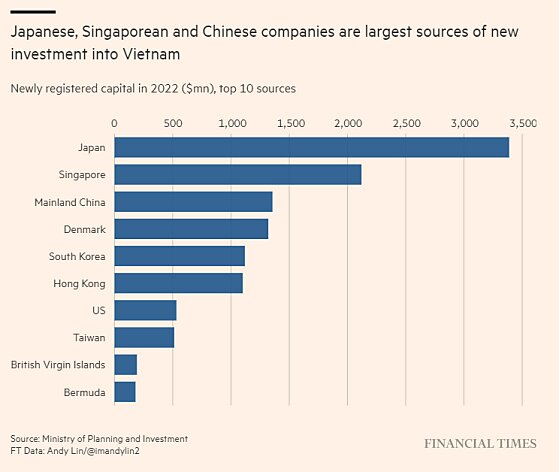

Indeed, Chinese companies are some of the biggest investors in Vietnam:

The reshaping of US imports away from China may not have reduced dependence on China as much as import numbers suggest because countries that were more deeply engaged in Chinese supply chains experienced the most rapid export growth to the US. In particular, we find evidence that countries that saw faster export growth to the US in certain sectors also had more intense intra-industry trade with China in those same sectors. Specifically, our estimated coefficients imply that an increase in the bilateral intra-industry trade index with China from the 25th to the 75th percentile is associated with higher export growth to the US market of around 3 percentage points for all tariffed products and 4.5 percentage points for strategic goods.

Thus, they conclude that “to displace China on the export side, countries must have embraced industry-wide supply chains with China.” Data from the OECD, which are only through 2018, draw similar conclusions: Both U.S. exports to and imports from China are higher in terms of value-added (i.e., actual content) than they are in gross terms (i.e., what the standard trade stats say).

So much for that decoupling, eh?

This outcome may surprise laypeople (and is certainly missed by many journalists and wonks talking about “decoupling” today), but it’s unsurprising to folks who understand global supply chains and U.S. customs law. The latter classifies a manufactured good from countries like India and Vietnam, with which we don’t have free trade agreements (FTAs), as “originating” in that country when the product’s imported inputs undergo a “substantial transformation” (i.e., the inputs, as a result of further manufacturing, become a different product having “a new name, character, and use”). This “rule of origin” is complicated, subjective, and fact-specific, but it can actually be easier to meet than many U.S. free trade agreement rules of origin, which often dictate that a good can “originate” in an FTA country (and thus benefit from lower tariffs and other FTA terms) only where a majority of its value comes from one or more FTA countries. Thus, for example, a product with more than 50 percent Chinese content might be found to “originate” in Vietnam (and thus avoid U.S. tariffs) but might stay “Chinese” (and face tariffs) if it undergoes the same manufacturing process in Mexico, a U.S. FTA partner subject to often-stricter rules of origin. (Yes, this makes little sense, but … here we are.)

As a scan of the internet readily demonstrates, U.S. trade lawyers are well aware of this situation and have been working with multinational clients to shift just enough manufacturing—including final assembly and some inputs—out of China to qualify as “originating” in a non-China country and to thus avoid the trade war. To safeguard their clients’ investments, these lawyers often seek official rulings from Customs and Border Protection to confirm that their new “non-China” manufacturing processes constitute a “substantial transformation” of Chinese inputs. And a quick review of those rulings indicates that business has been booming: In the five years before the trade war (2013 to 2017), about 152 customs rulings mentioned “substantial transformation” and China; in the five years since, that number has risen to 1,039. (Note: These numbers have been updated.)

This is admittedly a simplistic analysis—some of the increase, for example, probably isn’t trade war-related—but the trend is still clear. And literally any trade lawyer in Washington can confirm it.

Most “decoupling” discussions, on the other hand, miss the issue (and its implications) entirely.

‘China Plus One’

This doesn’t mean, of course, that multinationals aren’t diversifying away from China—whether because of geopolitics, the CCP’s bad behavior, or economics (e.g., slower growth or higher costs in China). But it does argue for more nuance than is being applied today when talking about “decoupling.” In particular, diversification is often less about abandoning the mainland than it is about adopting a “China plus one” strategy in which companies essentially develop two supply chains—one for China and one for the West (emphasis mine):

As rivalries grow between China and the US over technology and security, more companies fear curbs on what and where they can manufacture. As a result, many are supplementing production in China, still the world’s biggest manufacturing hub, with expansion to other countries.

“Koreans, Taiwanese, Chinese— there seems to be an unstoppable transfer or at least relocation from mainland China into other countries,” said Koen Soenens, Deep C’s sales and marketing director. “Foreign companies currently in China, ask them what’s next. [They say] ‘For the Chinese market, we stay in China; to serve our overseas clients, we are looking for a new location’.”

This necessarily involves some diversion of investment away from China, but it’s not the wholesale divestment that “decoupling” discussions often mention and China hawks dream about. For many firms, the massive Chinese market, for all its warts and for better or worse, remains too attractive for that—especially for companies not based in or dependent upon the United States (another thing the “decoupling” discussions rarely mention).

Summing It All Up

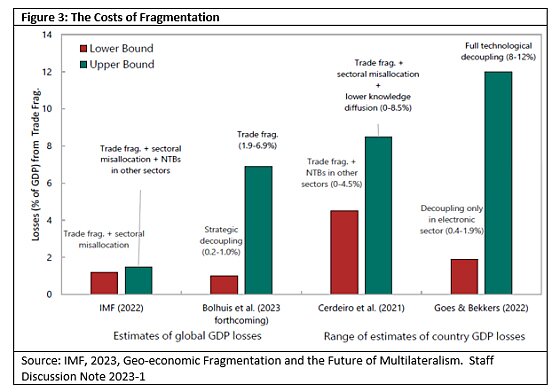

As Packard notes, perhaps these enormous costs would be worth enduring if there were a strong likelihood that even more global trade and investment restrictions would cause the CCP to abandon its economic, foreign policy, and human rights transgressions. But, after five-plus years of tariffs, sanctions, and worsening CCP behavior and U.S.-China relations (not to mention creative supply chain reconfigurations and lawyering), such an outcome is fanciful at best.

https://t.co/u1MVg8wmSD pic.twitter.com/3N0cf2WLaI

— Scott Lincicome (@scottlincicome) June 29, 2023

These “hard decoupling” fantasies also suffer from practical deficiencies. Most obviously, they ignore whether such an outcome is even possible, given the complexity and fluidity of the 21st century global economy and the central positioning of the U.S. and China therein. “New Cold War” nonsense aside, the points above hopefully show that this isn’t the Soviet Union in 1950, and we can’t just turn this stuff on and off like a lightswitch, regardless of whether we should. Policy–and the folks who write about it–should act accordingly.

Similarly, decoupling dreams ignore the vast amount of staffing and resources that the United States and allied governments, as well as private individuals and companies, would need to devote to implementing and enforcing a hard break from the Chinese economy. Federal law already enacts some restrictions and screens on a limited scale (e.g., with respect to slave labor and national security-related investments). But, as the Peterson Institute’s Adam Posen recently noted, the economic coercion needed to block almost all bilateral trade, investment, and migration (including inputs and investment funneled through third countries) would—costs notwithstanding—require the United States “to become a commercial police state on an unprecedented scale” and “to monitor and prevent its own headquartered companies from moving activities abroad.”

You’d think.

Chart of the Week