Dear Capitolisters,

The U.S. labor market is a conundrum right now—and it’s slowing the economic recovery. The most recent U.S. jobs report, like the August one before it, significantly undershot economists’ forecasts. Even though we’re still far short of pre-pandemic employment levels and supplemental unemployment benefits have ended nationwide, job openings in the United States remained near record highs. Workers are also quitting at a rapid clip, and union strikes are popping up across the country—despite a still-sagging labor-force participation rate (the percentage of American adults working or actively looking for work). Now, instead of several reports showing millions of new jobs like the Federal Reserve and others expected, U.S. companies and economists are increasingly warning that the “labor shortage” could be a major drag on economic growth.

Surely, some of this is just the pandemic doing pandemic things: the Delta variant, school and daycare challenges, continued government restrictions, and closed businesses surely affect the job market, especially at the local level. On the other hand, it feels like something else is going on here, beyond just the pandemic stuff. And it has me wondering whether the U.S. labor market has changed in more fundamental ways than we currently think.

Things Aren’t That Bad

Before we get to that, however, here’s a quick reminder not to overreact to one jobs report (or even the last two). Indeed, as Harvard’s Jason Furman noted in a recent blog post, there were some signs of life in the labor market last month:

Much of the other data in the report was considerably more positive than the headline including: private sector jobs were up 317,000 with some indication that seasonal adjustment issues were behind the large fall in public education jobs, hours were up sharply, the unemployment rate fell by 0.4 percentage point (the second largest decline of any month this year) and the Black unemployment rate fell by 0.9 percentage point, nominal wages were up 0.6 percent (even faster than the very fast pace in the first eight months of the year and continuing the fastest growth for production and nonsupervisory workers since the early 1980s), and the data showed positive revisions for previous months.

He helpfully adds that the data for the September employment report largely came before Delta variant concerns started to wane, and it could take at least a month for any effects from September’s unemployment insurance expiration to show up in the national data. The New York Times’ Neil Irwin echoes these points, which do (I think) rebut the sky-is-falling rhetoric you may have heard from various partisans when the jobs report came out. It’s certainly possible that things will be much better in the next few months.

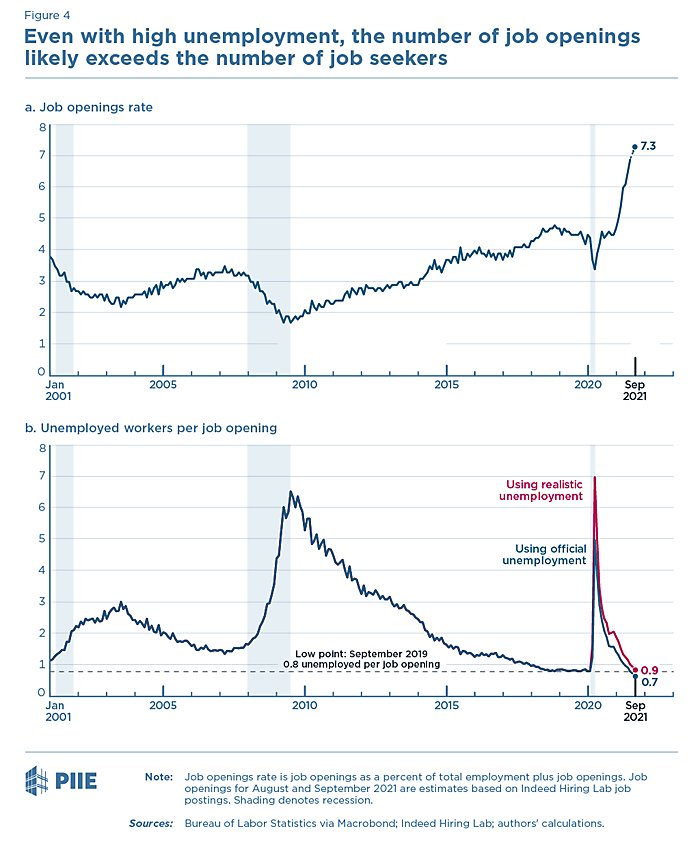

That said, even the sanguine Furman notes some reasons for longer-term concern about the U.S. labor market situation. In particular, the United States remains about 7 million jobs short of pre-pandemic trends, even with about 11.7 million job openings and significant upward pressure on wages that should be pulling people back to work:

Furman expects several million more jobs to be added to the rolls in the coming months given current market dynamics but also warns that we could still end up millions of jobs below pre-pandemic projections “if people have left the labor force for good (e.g., due to early retirement) or if other changes have permanently reduced labor demand (e.g., employers hiring fewer workers who are higher skill and higher paid).” His hope is that “all the jobs can be regained”—eventually.

There are already some signs, however, that this just isn’t the same labor market that existed in early 2020—and these signs seem to be growing by the day. If that’s right, it has some serious implications for not only the U.S. labor market, but also all sorts of economic policies in place or under consideration.

So What’s Driving the “Labor Shortage”?

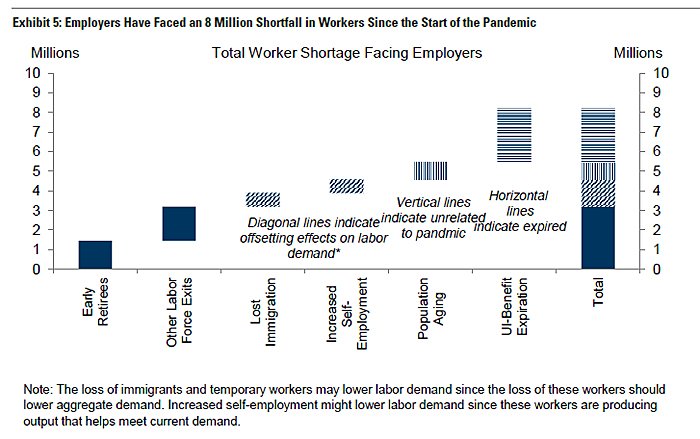

In an excellent report that preceded the September jobs report (no link—sorry), Goldman Sachs analysts saw a “perfect storm of factors that have significantly reduced the supply of workers who are currently looking for jobs at the same time that labor demand—as measured by job openings—has risen to an all-time high.” This includes, as shown in the chart below, state and federal benefits, early retirements, severely restricted immigration, a switch to self-employment, fear of COVID, and a geographic mismatch between unemployed workers and available jobs. Combined, these factors account for most of the missing workers out there.

Many of them, Goldman asserts, are temporary and will “ease considerably this fall—especially following the expiration of federal UI benefits programs in September,” but they “still project an over 1mn hit to the labor force from early retirees and other labor force exits at end-2022.” Thus, wage pressures and other issues could persist for quite a while.

However, there is already some evidence that even the short-term factors might not be as short-term as Goldman and others think. And the permanent ones could also be a lot larger.

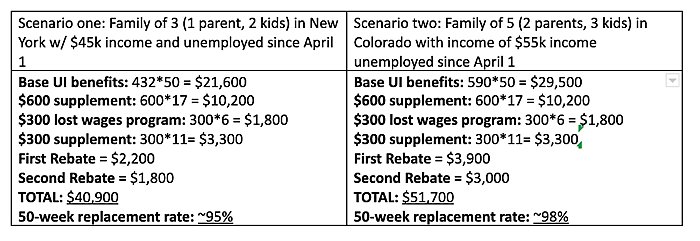

For starters, many workers’ financial position has changed, due in part (but not entirely) to past and current government assistance, and this may be helping them stay on the sidelines for longer than economists expect. While almost all the academic debate has focused on the effects of supplemental unemployment benefits on labor supply, there’s been far more government assistance provided to workers than just UI—assistance that’s been mostly ignored. (In this regard, I also plead guilty—at least early on.) Recall this chart from back in February to get an idea of the range of federal assistance that has been made available to American families during the pandemic:

Since then, there’s been even more support: Most notably, the American Rescue Plan sent out tens of millions of additional “Economic Impact Payment” checks to most Americans (up to $1,400 per adult and $1,400 for each dependent) and started monthly disbursements of larger, refundable child tax credits (up to $3,000 to $3,600 per child, depending on his age). Other assistance, such as food aid or rent relief, was also provided.

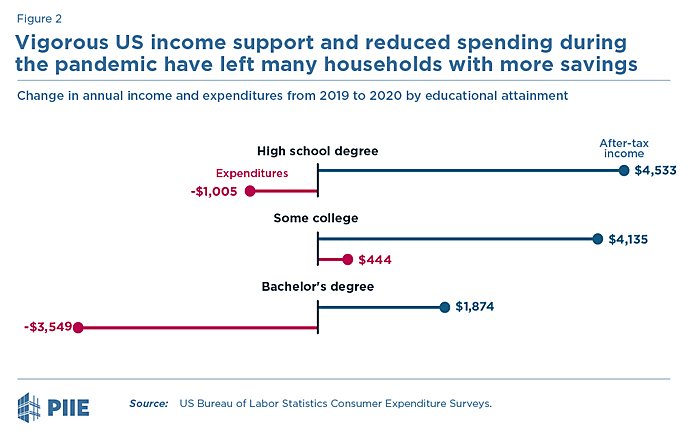

Americans have also been spending less—for policy and non-policy reasons. Most obviously, pandemic-related closures caused Americans to do without big-ticket things like vacations and smaller things like movies or car repairs. And the historic collapse in mortgage rates over the last year let many homeowners reduce monthly mortgage payments by a substantial amount (myself included). Other Americans saw their monthly expenditures decline even further where they benefited from government student loan or rent relief programs—several of which remain in place through the end of the year. (The federal rent moratorium expired but many state-level moratoria remain in force.)

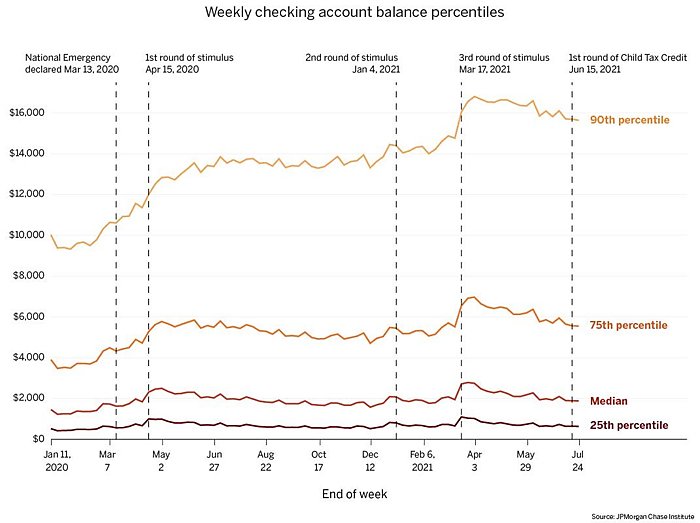

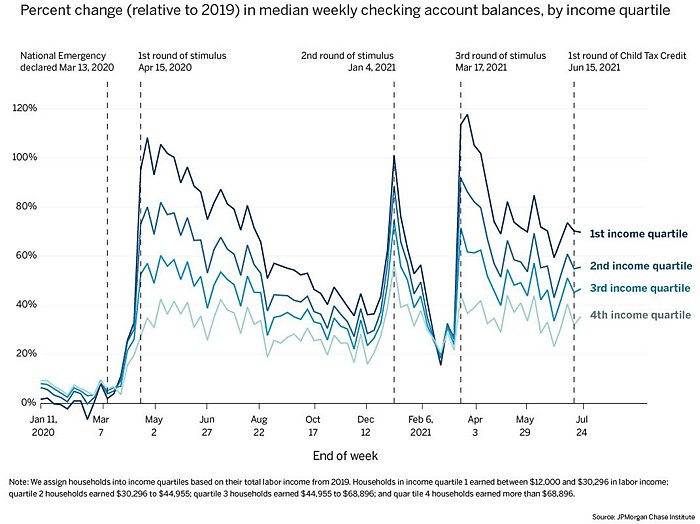

Combined, this means that a lot of unemployed workers could have a lot more cash socked away than we currently think:

A recent analysis from JP Morgan adds that “[m]edian cash balances are more than 50 percent higher as of the end of July 2021 compared to the same period in 2019”—thanks in large part to government payments.

The academic debate over supplemental UI and labor supply continues to rage—Goldman’s economists see a big effect (more than 1 million jobs), others see smaller ones (or say it’s too soon to say), and others still see little to none. (I recommend reading the links here before yelling about UI in the comments!) Most of that debate, however, ignores other forms of government assistance and Americans’ overall financial cushion—factors that, when combined with psychological or emotional changes brought on by the pandemic, could let many workers remain out of the labor market for far longer than most economists expect, maybe even permanently.

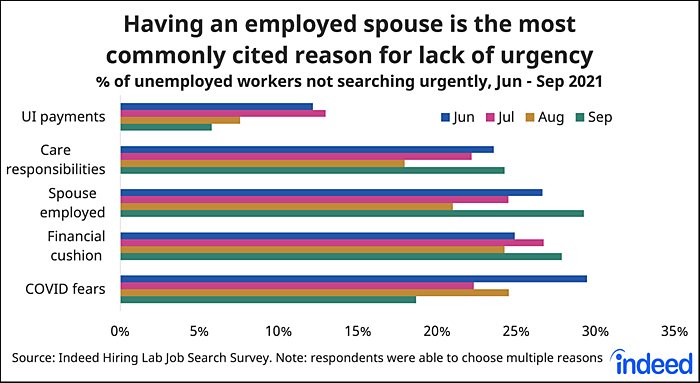

A recent New York Times piece and a separate one from the Wall Street Journal provide several anecdotes along these very lines—anecdotes that also coincide with the latest survey data from job search company Indeed:

All of these points (and plenty of other stories) relay a similar message: After spending a few months out of the labor market thanks in no small part to government assistance, some Americans are—for whatever reason—deciding to stay out (at least for now). Whether this is a “good” or “bad” thing is another matter entirely (I think it’s probably a mix of both), but for today it’s just important that we acknowledge the trend.

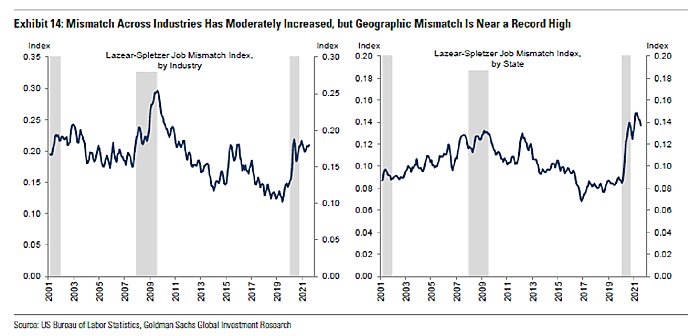

Second, the geographic mismatch between job openings and available workers, which Goldman sees at record highs (see chart below), could also persist for longer than forecast.

Through August, workers were looking for jobs in places—especially urban centers still subdued by the pandemic and by the broader shift to remote or hybrid work—where they lived but jobs just weren’t available. Some of this mismatch is sure to continue for a while longer: For example, many cities will rebound once Delta is behind us, but some might not. And economic activity in all of them could be subdued by post-pandemic changes to office culture and could move out to the suburbs and exurbs where many now-remote workers live. Of course, unemployed workers can move to new job opportunities, but geographic mobility in the United States has been declining for decades (thanks in part to bad government policies, by the way). The current geographic mismatch could therefore persist for longer than we currently expect, putting further downward pressure on the jobs numbers.

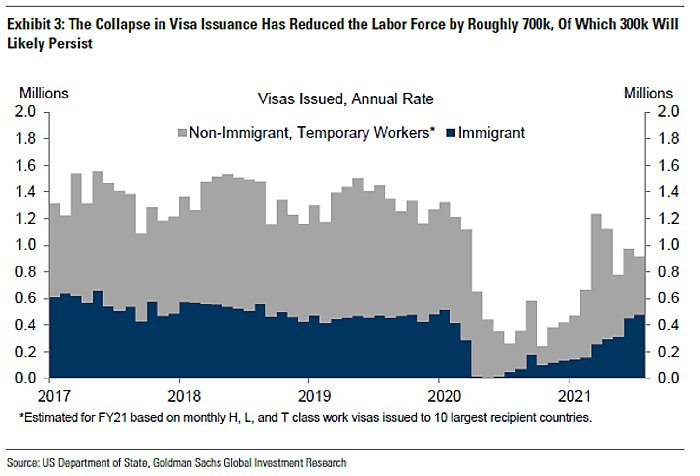

Third, immigration restrictions could ease in the coming months, but that could still keep the U.S. labor market short by hundreds of thousands of immigrant workers. Goldman estimates, for example, that the collapse in U.S. visa issuance has reduced the labor force by 700,000 workers, and will still be short by 300,000 once normal operations resume:

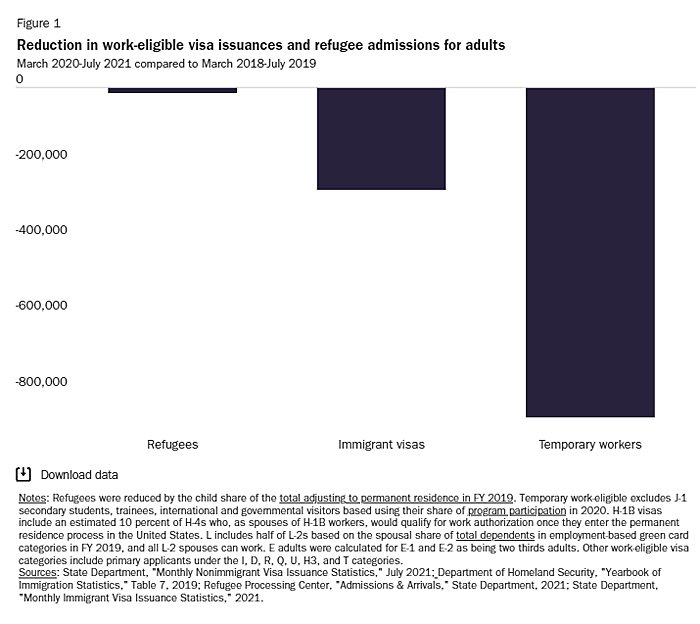

My Cato colleague David Bier says that the situation is actually even worse than Goldman estimates:

[T]he U.S. government has issued about 1.2 million fewer visas to adult immigrants, refugees, and temporary foreign workers abroad since consulates were closed in March 2020 through July 2021 compared to the period from March 2018 to July 2019 before the pandemic.

In the 2018–19 period, 2.2 million work-eligible visas were issued to adults, and there were only about 1 million issued in the 2020–21 pandemic period. The 1.2 million fewer visas include about 14,000 adult refugees, 270,000 adult immigrants (permanent residents), and 872,000 adult temporary workers and their spouses eligible for work authorization (Figure 1).

Even more maddening, the United States can’t simply make up the difference going forward, as a recent Bloomberg editorial explains:

Each year, the U.S. issues a maximum of 140,000 green cards to immigrants sponsored by employers and approved for permanent residence — a number frozen since 1990. Another 226,000 “family preference” green cards are reserved for family members of U.S. citizens and permanent residents. In years when the ceiling for family preference visas is not reached, due to low demand or processing delays or both, the unused visas move to the employment-based category, but have to be awarded by the end of the next fiscal year.

The closure of immigration offices during the pandemic, along with restrictions imposed by the Trump administration, caused the number of family-preference green cards to plunge in 2020. As a result, 122,000 additional employment-based green cards became available. That should have been good news for workers in the green-card queue, some of whom have lived in the U.S. legally for decades. But U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services was unprepared to handle the surge in demand. Despite a late push by the Biden administration, the agency fell well short of awarding the full quota by the Sept. 30 deadline. If Congress doesn’t act, those unused green cards will be lost for good.

Bier notes that, as of mid-October, “60 percent of consulates remained fully or partially closed to anything other than emergency nonimmigrant visa appointments, and 40 percent are completely closed to non‐emergency nonimmigrant visa appointments” for temporary foreign workers and other visitors to the United States. So don’t expect immigrants to be filling our job gaps anytime soon—especially given Washington’s frustrating gridlock on the issue.

Fourth (and as morbid and depressing as it is), we must account for the impact that COVID-related death and illness has had on the U.S. labor market. Economist David Kotok hit on this in a provocative essay this past April, examining potential “years of life lost” (YLL) from all excess deaths directly and indirectly caused by the virus, as well as long-term illness and caretaking (e.g., a family member):

By the end of this calendar year, we project a COVID shock of about 10 million YLL in the United States. That is a huge reduction in projected aggregate demand, because consumption by those million people over their projected average 9 lost years disappears. That is an addition to the baseline projection from the mortality tables. And I haven’t even touched the issue of the skills lost. The 100-year-old person who died of COVID in a nursing home counts as a COVID death but makes only a small contribution to this economic estimate. The 30-year-old nurse who died of COVID while caring for COVID patients in a hospital, on the other hand, makes large contribution to YLL and will be sorely missed, as will the 50-year-old engineer or computer scientist. So, too, the truck driver or teacher. COVID has killed many who are highly skilled, and it has killed many who had years yet to contribute to the labor force.

So we think this large gap will take years to fill. For example, we have recently seen job growth of nearly one million in a month. And we see a plunging unemployment rate. But we also see an increasing number of long-term unemployed. And we see that the total number of nonfarm employed is back up to 143 million. But do we remember that the figure was 153 million in the month before the COVID shock? In other words, instead of growing from 153 million to 155 million, we are now back up to only 143 million, not to where we were before.

Kotok’s estimate may end up being high (excess deaths are projected to be lower than his estimate), and most of the affected individuals were old and probably out of the labor market already. But, even with those caveats, we’re still probably talking about at least 200,000 working-age Americans, given that almost 170,000 Americans between 18 and 64 had died from COVID-19 as of last week. Up the age to 74, and it’s another 160,000 potential workers. These lost lives’ contributions to the labor market are of course of secondary concern, but they still must be noted when noodling the current situation.

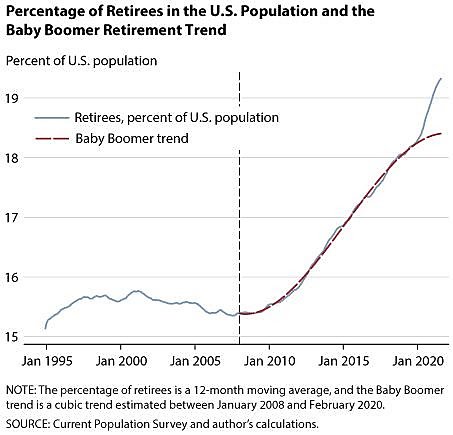

Finally, and most importantly, there appear to have been millions of early retirements that are probably permanent. Comparing actual retirements during the pandemic to previous trends for aging baby boomers, for example, the St. Louis Federal Reserve finds that “as of August 2021, there were slightly over 3 million excess retirements due to COVID-19, which is more than half of the 5.25 million people who left the labor force from the beginning of the pandemic to the second quarter of 2021.”

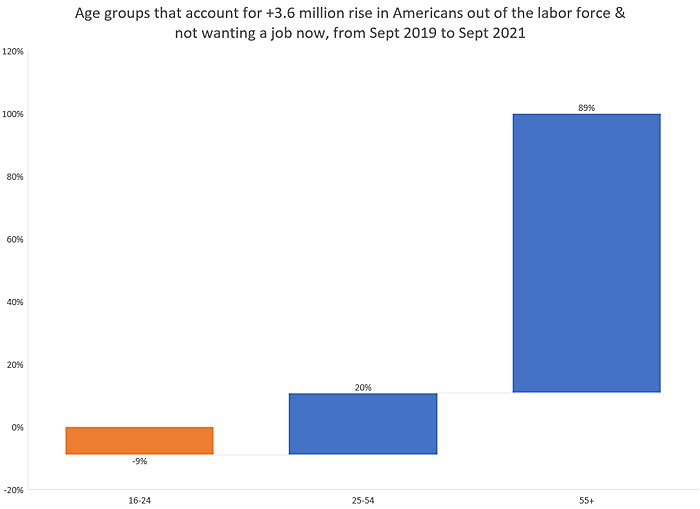

They then speculate that these retirements were likely caused by several factors, including COVID’s potential dangers to older people’s health or rising asset values (stocks, home values, etc.) that made retirement possible years sooner than retiree’s expected. Economist Aaron Sojourner finds evidence of the same: 89 percent of the 3.6 million Americans now out of the labor force but not wanting a job were above the age of 55.

Anecdotal evidence again backs this: The aforementioned WSJ piece, for example, cites two women—both in their early 60s—who decided to hang it up early instead of rejoining the labor force. Will they and millions of other retirees come back once the pandemic’s behind us?

Summing It All Up

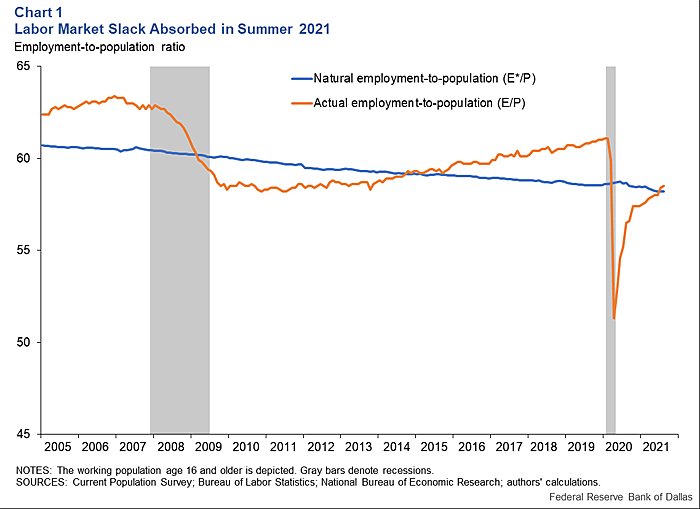

Several factors are affecting the current labor market, and many of those point to the current labor shortages persisting well into next year—if not longer. Indeed, earlier this month, St. Louis Fed economists projected that 3.6 million more workers will return to employment by June 2022, but that’s only about half of the 7.1 million jobs still missing when compared to pre-pandemic levels. Economists at the Dallas Fed, by contrast, say that the slack in the U.S. labor market has already been taken up.

Regardless of the labor market’s exact positioning at the moment, it seems pretty clear that it will remain really tight for the foreseeable future—driven by the aforementioned factors (and surely others). This matters not only for U.S. companies desperate to hire and U.S. consumers annoyed by sub-par service, but also plenty of other aspects of U.S. economic policy. Those ubiquitous supply chain problems, for example, are caused in part by a lack of workers for U.S. ports, importers, and freighters. Labor market slack or tightness also affects inflation and thus U.S. monetary and fiscal policy (as well as eroding recent wage gains). As a new JP Morgan analysis put it, returning workers “might not be enough to restore the pre-COVID balance of supply and demand in the labor market, which was already pretty tight. As a result, wage pressures and labor shortages may be an endemic feature of the post-COVID US economy and put pressure on the Fed by the middle of next year.” Labor shortages—in daycare, for example—also can breed other labor shortages, and can weigh on Democrats’ current social spending plans, which raise multiple concerns about pushing even more Americans out of the labor force.

And then, of course, there’s immigration: a persistent lack of workers and related economic challenges would—in a sane world—argue for a significant increase in U.S. immigration levels and a broader overhaul of our visa systems. As Bier explains, for example, we have not only a 1 million-plus backlog in pandemic-related visas, but about 9 million more people waiting in line! He adds that some liberalization could be done by Biden alone—alleviating some pressures (on both the economy and Biden’s economic agenda) and assuaging a top business concern right now—but that Bloomberg editorial shows that legislative action is needed too, for both the short and long term:

[The expiring visa situation] compounds the failure of a system that, even when running as intended, leaves hundreds of thousands of skilled and legally employed workers in limbo. On average, highly educated immigrants who’ve qualified for green cards can expect to wait 16 years before actually receiving them. Because of limits on the number issued to any single country, many immigrants from India who’ve been approved for permanent residence in the U.S. won’t ever get a card.

Legislation introduced by two Republicans, Senator Thom Tillis and Representative Mariannette Miller-Meeks, would authorize the government to “recapture” the expired visas and roll them into next year.

Given the factors outlined above and the potential for persistent labor shortages through 2022 (at least), legislation addressing both immediate and broader immigration reform needs would be economic no-brainers. Unfortunately, brains seem to be another thing in serious shortage these days.

Chart(s) of the Week

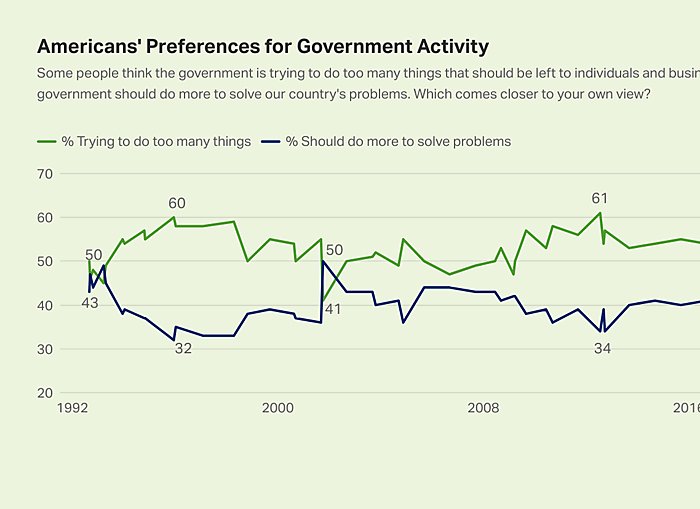

A blip or a trend? (link)

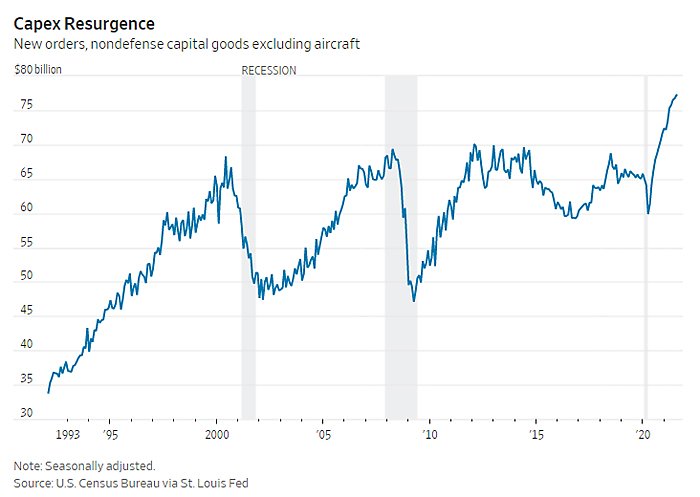

Ditto (link)

The Links

My long read on the supply chain mess, plus a short blog post on manufacturing, mercantilism, and economic resilience.

Truckers rail against “lazy” longshoremen

Trade and immigration restrictions are also contributing to the supply chain mess

Venture capital investment is booming

The State of the U.S. Rental Market

“School Choice’s Antiracist History”

California is scrambling for energy as it scuttles energy plants

Public pensions are loading up on risky investments

Yet another study showing that increasing inequality has been overstated

Speaking of U.S. inequality, it’s mostly an urban thing

What’s middle class in your state?

Zillow’s iBuying program falters

China growth falters and might not bounce back