Every national election concludes with an avalanche of thought leadership explaining how the results obviously demonstrate that the author’s pet economic issue was critical to the outcome and, of course, that he or she has been right along. If only candidate X had trumpeted economic policy Y and hewed closer to the author’s own worldview, so these things always go, she could have prevailed over candidate Z, who clearly tapped into the voters demands for said economic policy/worldview.

It’s a biannual tradition, and it’s almost always rather silly.

Capitolism will not indulge in such fantasies. Even in normal years, it’s unwise to assume that a single economic policy or a coherent policy framework—conservative, progressive, libertarian, post-neoliberal, whatever—propelled a national candidate to victory. Voters are complicated, don’t think deeply about most policies (especially things like tariffs!), and cast their votes for lots of personal or noneconomic reasons. Drawing strong economic policy lessons from this election is especially unwise, given each candidate’s historically unique situation and our historically unique pandemic/post-pandemic landscape.

Nevertheless, it is a good time to look back on the Biden years and consider whether and to what extent economic policy actually did play a role in last week’s outcome. Based on the early analyses, at least, there does appear to be one glaring economic issue that motivated many voters to pull the lever for Donald Trump—inflation—and several glaring errors from the Biden administration. Though these errors might not have driven Kamala Harris’ defeat, in hindsight they probably made things even harder than they already were.

It’s (Well, Was) the Inflation, Stupid

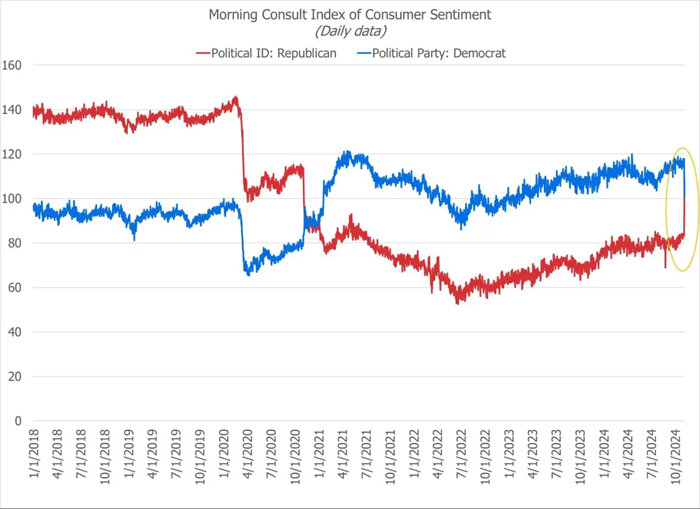

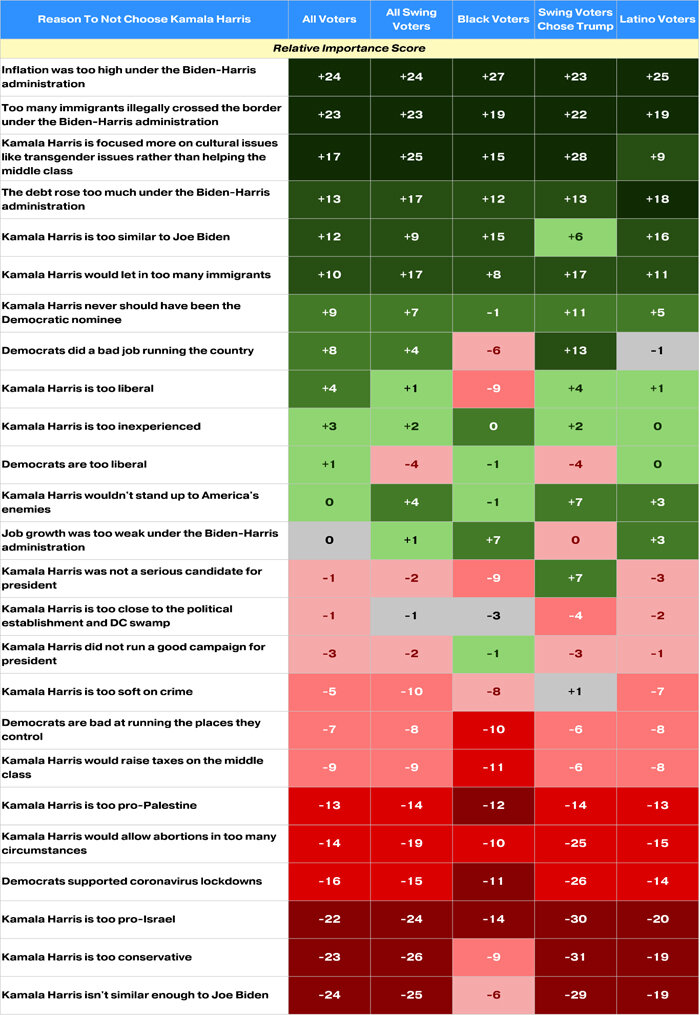

Other things played a big role last week, but, among the economic issues at play, inflation stands alone. Here, for example, is the postmortem polling by Blueprint 2024, which shows that inflation topped the list for why voters didn’t choose Kamala Harris:

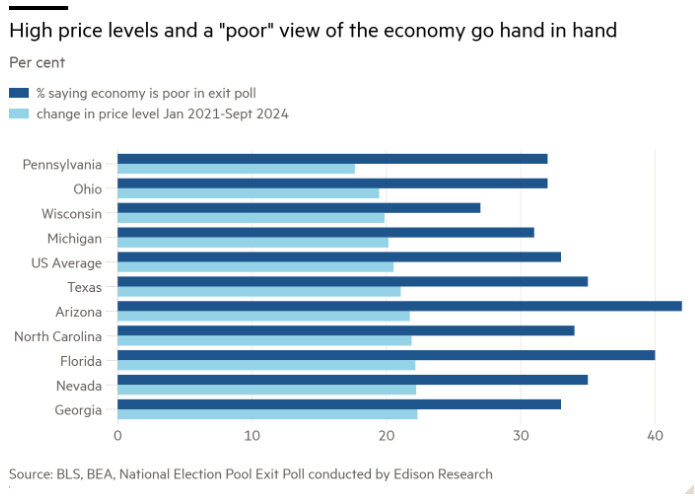

In the Financial Times, meanwhile, we see that inflation since 2021 was closely connected with swing state voters’ views of the economy:

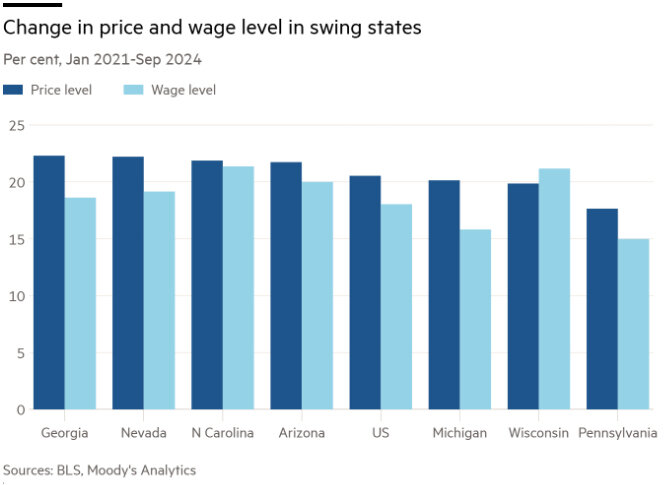

And we see that price increases generally exceeded wage increases in these critical places over the same period:

Plenty of other data points and anecdotes all come to the same conclusion: Even though inflation has moderated a lot in recent months, and even though the U.S. economy was (is) generally humming along, the dramatic, generational price increases we all experienced in 2021–23 left a deep scar on most voters’ minds. Elections expert Sean Trende sums it up well in his immediate post-mortem:

Inflation is bad. This issue has been covered deeply, but it bears repeating: When unemployment is 10%, that means 90% of people are employed. Those with jobs might be nervous, they might not get raises, they might feel for those who are unemployed – but the brunt of the problem falls on a small subset of the population. It’s also usually resolved fairly quickly, as unemployment typically reverts to healthy levels in a year or so.

Inflation is different. It affects everyone. It affects them every day in everything they do. And its impact is cumulative: When the inflation rate flattens out, prices are still high. It takes a long time for expectations to reset. It’s among the worst things that can happen to an incumbent president, and Harris refused to distance herself from the administration that oversaw the worst inflation in 50 years.

At the risk of injuring my shoulder from all the back-patting, this parallels what I said a year ago when explaining that, despite recent improvements in the U.S. economy, it was perfectly understandable that normal Americans were still fuming about high prices and, relatedly, high interest rates. Research shows, in fact, that most people don’t think about inflation like economists (i.e., examining the current rate of price changes) and instead simply consider whether prices are higher today than they were within recent memory. They want outright deflation, which few (if any) economists want; it can take months or longer for disinflation to take hold in normies’ minds; and they will viciously punish incumbents if they still think it’s bad.

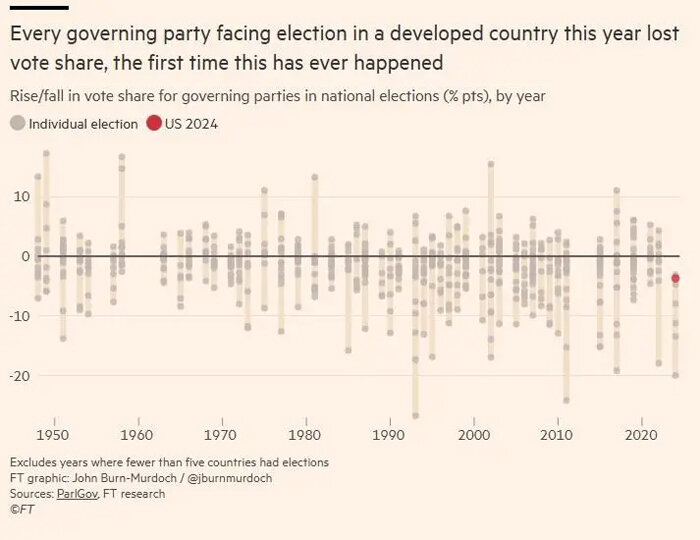

Thus, as the FT’s John Burn Murdoch shows, voters sanctioned every incumbent in the world this year—the first time in history that’s happened:

As Murdoch puts it, “Voters don’t like high prices, so they punished the Democrats for being in charge when inflation hit.” Maybe those same Democrats could never have escaped such a beating, but they certainly didn’t need to encourage it.

Yet that’s just what they did—and then they bragged about it.

They Went Big—Repeatedly—and Then Called It All ‘Bidenomics’

Probably the biggest mistake was the Biden administration’s and congressional Democrats’ repeated decision to “go big” on government spending, starting with the $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan and then continuing with several massive “industrial policy” laws—the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, CHIPS Act, and Inflation Reduction Act—potentially spending trillions more.

Specifics of the ARP aside, it was broadly ill-conceived in two big ways. First, its timing was off. As we discussed way back in February 2021, the ARP’s general outline was first crafted when the U.S. economy was in a much more perilous position—before vaccines began to proliferate widely and economies began to reopen—than it was when the bill finally became law in March of that same year. By that time, it was abundantly clear that the ARP would be adding rocket fuel to an economy that had already started taking off—thanks in part to previous rounds of government stimulus.

Second, the ARP erroneously assumed that the pandemic recession was much like the Great Recession, which supposedly taught us that fiscal stimulus should always “Go Big” to avoid a prolonged labor market funk. As I noted in 2021, this assumption suffered from several flaws:

This ignores (1) that the pandemic recession is likely different—in cause, effect, and duration—than the deeper, more systemic Great Recession (see, e.g., this new paper from Michael Strain and Jay Shambaugh on the latter); (2) that the $4.1 trillion in authorized pandemic recession fiscal support has already doubled the fiscal policy responses (about $1.8 trillion) to the Great Recession; (3) that Federal Reserve actions during the pandemic recession have also been, in the words of Chairman Jerome Powell, “unprecedented”; and (4) that overshooting the output gap by two- or three-fold carries its own risks.

One of those risks I mentioned was the ARP’s potential to spark a “serious bout of inflation”— something many left-leaning economists were also worried about. Since then, of course, we did suffer such inflation, and wonks have vigorously debated how much the ARP—along with monetary policy and supply-side shocks—contributed to the rapid run-up in prices that we experienced in 2021–23. AEI’s Michael Strain estimates that the ARP was responsible for around 3 percentage points of peak inflation; Hoover’s John Cochrane finds a strong connection between a country’s inflation and its fiscal expansion; both the San Francisco Fed and St. Louis Fed came to similar conclusions; and a group of academic economists did too (“aggregate demand shocks explain roughly two-thirds of total model-based inflation, and … fiscal stimulus contributed half or more of the total aggregate demand effect”). Other academic research finds similar effects, which were both larger than and different from the inflation being felt in Europe and elsewhere.

Granted, most of this fiscal stimulus occurred under Donald Trump’s watch, and other academics think supply chain problems were a bigger driver of inflation in the United States. On the latter point, however, even most of the supply chain-focused analyses acknowledge “massive fiscal stimulus” playing a role. “In retrospect, fiscal policy overdid it,” the Wall Street Journal’s Greg Ip concluded in 2023, and, as Axios’ Neil Irwin just wrote, this meant more pain for voters than would’ve otherwise been the case: “If more restrained fiscal policy had resulted in inflation peaking even a couple of percentage points lower, the Fed would not have seen the need to raise rates by as much as it did, lessening another vector of recent economic pain.”

On the former point, meanwhile, the administration’s vocal championing of the ARP, along with good ol’ recency bias, likely moved many American voters to associate stimulus-fueled inflation with Biden, not Trump—something Republicans were naturally thrilled to encourage. Adding insult to injury, Biden and congressional Democrats followed up all that spending with … even more spending. The CHIPS Act cost a mere $60 billion on paper, but open-ended tax credits will take the bill much higher. The Inflation Reduction Act was alleged to be deficit neutral, but that claim was almost immediately called into question because of a similar underestimate of tax credit uptake. Now, it might cost more than $1 trillion. Those bills had identifiable benefits too, of course, but—as we discussed previously—the occasional press conference on a new factory in some random place was simply no match for the daily reminder of economic pain and uncertainty that inflation brings. Put it all together and then cheerfully call the whole thing “Bidenomics,” and you had even many Democrats second-guessing the “Go Big” strategy in early 2024.

Now we know they were right to worry.

Then Came the Inflation Denial

Those worries were further compounded by the repeated insistence by the White House and its progressive allies in 2021 and early 2022 that the inflation we were all clearly experiencing was both “transitory” and isolated to a few random categories like—and I kid you not—food, energy, shelter (housing/rents), and transportation (automobiles). As I showed in November 2021, moreover, public projections of the inflationary period’s depth and duration kept being far too optimistic, fueling further public doubt and anger about prices. It was only in mid-2022 that the White House moved to tackle inflation head on, as the Washington Post reported at the time:

The White House has grappled unevenly with how to respond to this threat since it emerged last summer. The administration initially downplayed the extent of the problem, inaccurately saying it would prove “temporary.” When price increases persisted, the administration pivoted last fall to acknowledging that inflation was real but arguing that the Democrats’ Build Back Better legislative agenda was best suited to respond to families’ cost pressures.

After that, we got clumsy and widely panned efforts to claim victory over inflation because things like turkey, gas or hot dog prices had dropped a few cents (never mind the many extra dollars everyone was still paying). As Harvard’s Jason Furman detailed last week, we also got endless cherrypicking and flat-out misdirection about all sorts of inflation-related measures of Americans’ well-being. And, when consumer sentiment and Biden’s approval ratings still hadn’t budged, the inflation denialists moved to blaming it all on “greedy corporations” (including Capitolism’s favorite economic villain, Big Egg).

Maybe some of this stuff swayed some voters in the end, but it was all cleanup for larger past mistakes. And it pales in comparison to a hypothetical world in which President Biden leveled with voters in mid-2021 that, because of (in his view) essential fiscal and monetary stimulus and pandemic-related supply chain problems, painful inflation was here and might stick around for a while, but—mark his words—he’ll spend every waking moment laser-focused on fighting it with every tool he’s got.

Instead, the president celebrated the ill-named “Inflation Reduction Act” and took a premature victory lap.

And Then Came More Tariffs and Protectionism

There were, in fact, several tools that Biden could have used to ease some of the price pain yet remained firmly in an Oval Office drawer. As we discussed in 2022 when inflation was at its peak, chief among them was tariffs and other U.S. trade restrictions. In particular, economic analyses showed that, while lowering trade barriers wouldn’t solve inflation, it would provide a significant, one-off reduction in the prices of many goods.

Most fixes are out of the president’s hands, and every little bit helps—especially for a White House supposedly putting “all tools on the table to beat inflation.” Thus, as [economist] Furman told Axios recently, “Removing the China tariffs is the single-largest policy lever to bring down inflation that President Biden has.” This solution should come as no surprise to the president. His own treasury secretary (and former Fed chair), Janet Yellen has, for example, repeatedly acknowledged that lifting U.S. tariffs might help cool prices a bit. Deputy National Security Adviser Daleep Singh recently said the same thing. Indeed, in targeting our ports for anti-inflation action, the “blame the supply side” president has himself (tacitly) admitted that easing U.S. trade restrictions could ease inflation. New import competition might also push American corporations to lower their markups and accept lower profits—another target of Democrats’ economic ire. So you’d think, then, that a Biden administration laser-focused on inflation (and with limited options for congressional action) would be eager to use the ample discretion afforded to it under U.S. trade law to roll back any and all restrictions on imports.

Admittedly, nixing all the Trump-era tariffs was a political non-starter, but they didn’t cut a single one and then added even more, along with other forms of price-inflating protectionism, such as enhanced “Buy America” restrictions for infrastructure and IRA-funded green energy projects—restrictions that not only increased prices but also delayed the projects’ rollout. The union-soaked politics of all this “worker-centric” protectionism are obvious, but, as left(ish) Matt Yglesias warned in May of this year, it came at a huge price (no pun intended): additional fuel—financially and rhetorically—to the White House’s biggest economic fire, inflation.

The move proved doubly problematic once Trump won the GOP nomination and went all-in on tariffs (sigh). Indeed, one of Harris’ most frequent and economically literate lines of attack against Trump was that he was recklessly proposing a global tariff that would further increase U.S. prices and potentially cost American households, already struggling from years of inflation, additional thousands of dollars per year. Her commercials and text messages repeatedly warned of this “national sales tax,” which experts on the left, right, and center loudly agreed was misguided (to put it nicely). Yet because of the Biden administration’s own protectionist trade policies (which they vocally championed, of course), the immediate counter from Trump and his supporters was simple: If tariffs are so bad, then why did Biden keep all of them in place? This also could have been a key area where Harris’ could’ve separated herself from Biden too, but she didn’t.

It was all, as the FT’s Alan Beattie just brilliantly detailed, a big mistake:

Whatever else the “worker-centred trade policy” achieved — it was almost certainly a net negative for the economy and jobs — getting blue-collar workers to vote Democrat wasn’t it. If working-class voters think the Democrats have abandoned them then that’s a messaging problem, or it’s because of other issues such as immigration, not trade. Inflation seems to have been a big issue with lower-income voters. And whatever else Biden’s trade policy achieved, it didn’t bring down prices.

A lot has been sacrificed in terms of economic efficiency, relations with allies and the international rule of law to no apparent end. If the Democrats ever get into power again, maybe they could have a shot at setting trade policy according to whether it will generate growth rather than being in thrall to an ideological and electoral calculus, which failed even on its own terms.

Amen.

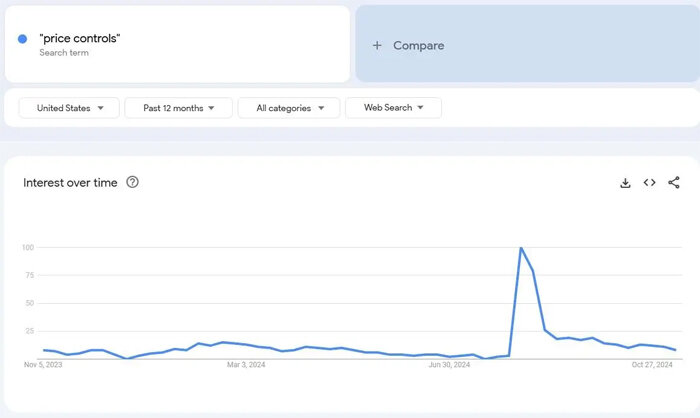

And Finally a ‘Price Controls’ Distraction

The Biden-Harris embrace of price controls was similarly misguided—not because voters didn’t like it (they sadly maybe kinda did?), but for three other reasons. First, it repulsed a lot of influential folks on the right and left who were most definitely not Trump supporters but also couldn’t help but loudly criticize the campaign for embracing a discredited policy that would make things even worse. This not only took Harris down a notch in the public eye but also led to days (weeks?) of confusion and debate about the perils of price controls and whether Harris actually did intend to implement them if elected.

Second and relatedly, the proposal fed right into the Republicans’ economic and cultural criticism of Harris—aka “Komrade Kamala” (sigh)—as a far-left California radical who’d both destroy the U.S. economy (and force us all to have taxpayer-funded gender reassignment surgery or something). Both problems were concisely summarized by the hilarious title to center-left Washington Post columnist Catherine Rampell’s column on the subject:

Finally, the candidate’s embrace of price controls distracted from other, better policies buried in her playbook that actually would help moderate food and housing prices. On the latter, for example, Harris was firmly in the mainstream when she proposed boosting housing construction and supply by tying federal subsidies to state and local deregulation (which is the biggest driver of supply and prices). Other Harris housing proposals weren’t nearly that solid, of course, but they were all lightyears better than federal price controls for the aforementioned reasons. Yet nobody talked about any of those things—they talked about price controls for weeks.

Even though the Harris campaign quickly walked back the proposal’s worst elements once the aforementioned influencers trashed it, the damage here had been done.

Summing It All Up

Inflation wasn’t the only thing that drove last week’s election results, but it was nonetheless a big driver—more so than even I, acutely aware of how much voters hate high prices, expected. And while inflation had cooled and Kamala Harris didn’t deserve all or even most of the blame for the previous run-up in prices, she and her colleagues in the Biden administration undoubtedly made things worse in several important ways. They spent too much, ignored too much, and instead of seriously taking our obvious inflation problem head-on, they and their progressive friends threw a “post-neoliberal” parade. Correcting for those mistakes might not have won Harris the election, but it probably would’ve helped. And when you’re already swimming upstream, it’s best not to wear an anchor.

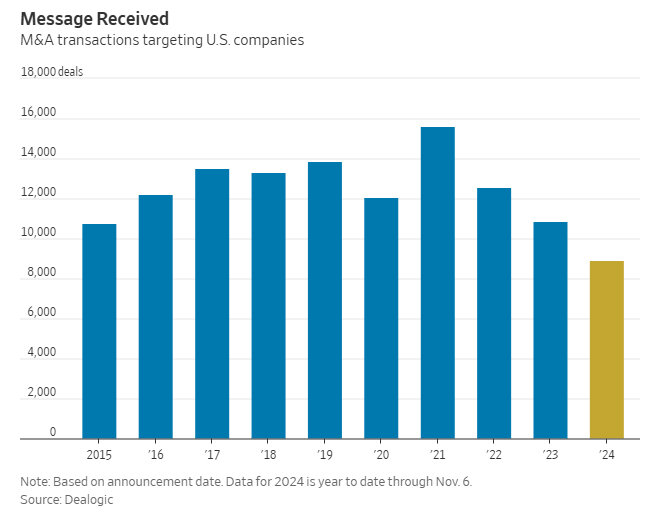

Chart(s) of the Week