Dear Capitolisters,

A couple months ago, I briefly discussed two analytical techniques, “stated preference” (what people say they’ll do in certain situations) and “revealed preference” (what they actually do), used to measure people’s willingness to wait in line. (You probably missed that part because you were too busy resisting my wisdom in the comment section.) In politics and policy, it’s smart to examine people’s stated and revealed priorities, because they often differ—and sometimes dramatically. People say, for example, that they really care about buying American (or whatever), but put an actual price on doing so—and make it anonymous—and Economic PatriotismTM turns out to be not much of a priority at all. Politicians’ differentials are often even wider: They say they deeply care about all sorts of stuff, but—put that stuff to a vote in actual legislation—and their priorities can shift.

Boy, can they shift.

I bring this up because Congress and President Biden have been really busy these past two weeks addressing all sorts of existential “crises”—American deindustrialization, China’s tech ambitions, climate change, etc., that they say they care deeply about. Yet dig into the actual legislation they’re championing, and you find a different set of priorities—priorities that often undermine the very things that supposedly demand urgent legislative action and, of course, mind-numbing amounts of taxpayer dollars.

Spot the Priority

Let’s start the just-passed CHIPS and Science Act, which provides, among other things, almost $80 billion in new federal grants, tax credits, and other subsidies (and maybe more, depending on uptake) to encourage the domestic production of semiconductors and related technologies. As faithful readers here know, I’m no fan of these subsidies, but my mainly economic arguments lost out to mainly geopolitical ones. In particular, the case was made that China—from both its own industrial subsidies or a potential invasion of chipmaking heavyweight Taiwan—is an existential threat to the global semiconductor market, which is essential for both national defense and the basic functioning of our modern economy. Thus, while economics might argue that we shouldn’t care where chips are made and that U.S. subsidies could generate distortions, in reality there’s a desperate need to incentivize the immediate onshore construction of additional chipmaking capacity by any means necessary—including an $80 billion taxpayer slush-fund with no serious domestic guardrails.

But just how much of an urgent priority is American semiconductor construction and production, really? Well, not enough to keeplanguage in previous versions of the CHIPS bill that would’ve expanded access to the foreign talent on which high-tech industries (here and abroad) today rely. Now, Politico reports, these and other U.S. immigration restrictions—according to not only semiconductor manufacturers like Intel and TSMC but also (quietly) members of both parties in Congress and various independent national security experts—imperil the whole semiconductor industrial policy effort:

[A] bewildering and anachronistic immigration system, historic backlogs in visa processing and rising anti-immigrant sentiment have combined to choke off the flow of foreign STEM talent precisely when a fresh surge is needed.

Powerful members of both parties have diagnosed the problem and floated potential fixes. But they have so far been stymied by the politics of immigration, where a handful of lawmakers stand in the way of reforms few are willing to risk their careers to achieve. With a short window to attract global chip companies already starting to close, a growing chorus is warning Congress they’re running out of time. …

“These semiconductor investments won’t pay off if Congress doesn’t fix the talent bottleneck,” said Jeremy Neufeld, a senior immigration fellow at the Institute for Progress think tank.…

“We are seeing greater and greater numbers of our employees waiting longer and longer for green cards,” said David Shahoulian, Intel’s head of workforce policy. “At some point it will become even more difficult to attract and retain folks. That will be a problem for us; it will be a problem for the rest of the tech industry.”

“At some point, you’ll just see more offshoring of these types of positions,” Shahoulian said.…

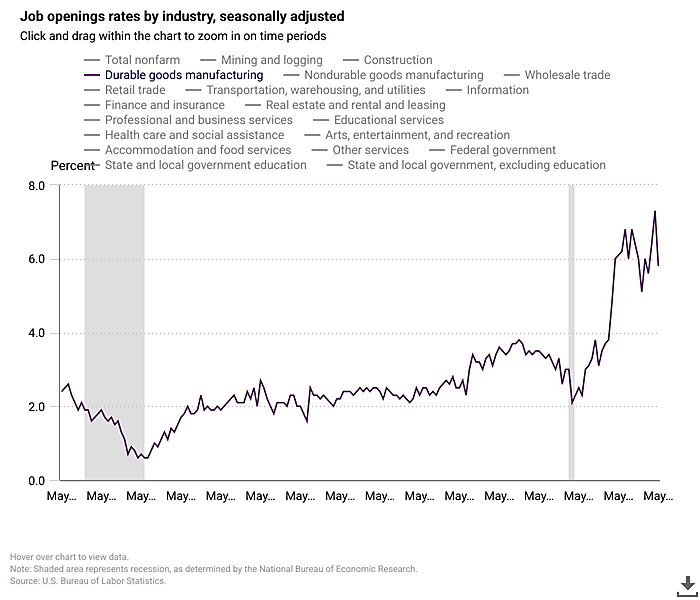

The article goes on to note that “Across the country, particularly in regions where the chip industry is planning to relocate, officials are fretting over a perceived lack of skilled technicians.” Those concerns shouldn’t be the least bit surprising. Most obviously, we’re in the hottest labor market in a generation, with about 800,000 job openings in manufacturing (500,000 for durable goods like semiconductors) and a tech unemployment rate of less than 2 percent.

And a lack of high-skill immigration has, as I’ve explained for the last two-plus years, been a major long-term concern for a U.S. semiconductor industry (which, contra the subsidy fans, remains a global powerhouse) highly dependent on STEM immigration. And Intel’s veiled offshoring threat has academic support: Past U.S. immigration restrictions have been found to encourage R&D‑intensive producers (like chipmakers) to offshore production to other countries, including China. Indeed, even the immigration-skeptical Trump administration quietly granted TSMC an unlimited number of visas to build its new fab in Arizona. Thus, as Politico notes, a new Government Accountability Office report on policies to boost domestic chipmaking found expert consensus on one issue: “a high-skilled STEM workforce was a barrier to new microchip projects in the U.S.—and most said some type of immigration reform would be needed.” Yet Congress dropped the immigration language from the CHIPS Act, and the semiconductor industry didn’t push for it (because they didn’t want to risk their sweet, sweet subsidies).

Congress also did nothing to ease tariff burdens on semiconductor manufacturers, even though—as I wrote late last year—chipmakers have repeatedly told the government that these taxes, which target not just materials needed to build fabs (steel, etc.) but also key chipmaking inputs, are a significant expense. In fact, the CHIPS Act, which was sold as necessary to offset higher chipmaker construction costs in the United States, actually raises those costs a bit because it expressly requires that funds for semiconductor facilities comply with “Davis-Bacon” prevailing wage requirements that are typically attached to federal infrastructure projects. That’s not only an unprecedented expansion of Davis-Bacon to private construction, but it’s also bad for the very projects the CHIPS Act is pushing, as these rules have been found to increase labor costs and reduce the supply of available workers (because they effectively exclude non‐union construction workers/firms, which represent more than 85 percent of the U.S. construction workforce). That’s great for Democrats’ union buddies, but it’s most definitely not great for expediting supposedly urgent “national security” projects across the United States during a national “construction labor shortage.” No surprise, then, that the main industry group representing U.S. builders and contractors vocally opposed this provision, warning it will increase costs, delay projects, and embroil small businesses in “red tape.”

Priorities!

A similar set of preferences has been revealed in the just-passed “Inflation Reduction Act,” which—misnomer aside—has been hailed by President Biden as “mak[ing] the largest investment ever in combatting the existential crisis of climate change.” Yet, as documented in a series of primers from the law firm White & Case (disclaimer: They’re my former employer, but I had nothing to do with these), major provisions attacking this “existential threat” are bogged down in protectionist restrictions that will inevitably increase costs, delay projects, reduce dissemination of “green” technologies, and (maybe) cause new trade disputes with major U.S. trading partners (not China). In particular—

-

Expanded tax credits for electric vehicles (EVs) include unsurprising China-related restrictions but go a lot further than that. In particular, subsidies are available for only “clean vehicles” whose “final assembly” is in North America—meaning that EVs assembled in Europe, India, Japan, Korea, and plenty of other non-China countries wouldn’t qualify. Furthermore, the full $7,500 credit is available only for vehicles in which (1) a substantial (and increasing) share of battery “critical minerals” come from the U.S. or a free trade agreement country (again excluding Europe, Japan, India, China, and others) and (2) a substantial (and increasing) share of “battery components” are manufactured or assembled in North America.

-

The IRA also provides new subsidies for “critical minerals” produced in only the United States, including through advanced manufacturing tax credits ($30 billion), “enhanced use” of Defense Production Act contracts ($500 million), and “innovative technology” loan guarantees. Again, this leaves out major non-China producers of these minerals, such as Australia or Canada.

-

Finally, the IRA bolsters tax credits for the production of zero carbon energy (wind, solar, geothermal, hydropower, etc.) in the United States. Once again, however, the biggest subsidies are limited to projects that meet two “Buy America” requirements: (1) all of a project’s iron and steel products must be produced in the United States; and (2) all of a projects’ manufactured products must contain set amounts of U.S. content. Furthermore, projects that do not satisfy these local content requirements would be disqualified certain subsidies, in whole or in part. As with the EV credits, these subsidies not only omit some of the biggest producing nations in the world, but might again raise new disputes with key allies like Canada, Japan, or the European Union.

But wait, there’s more! My Cato colleague Colin Grabow notes, for example, that—instead of waiving Jones Act restrictions that hamper the construction of offshore wind facilities in the United States (because Jones Act ships are insanely expensive and extremely limited)—the IRA simply throws subsidies at U.S. shipbuilders who already benefit from the Jones Act and oodles of other subsidies (yet remain terribly costly and uncompetitive).

Oh hey look, yet another subsidy for U.S. shipbuilding. I’m sure international competitiveness is just around the corner. https://t.co/WpOk78svRN pic.twitter.com/nxhLMYIbJw

— Colin Grabow (@cpgrabow) August 9, 2022

In all of these cases (and probably others we haven’t uncovered yet), protectionist conditions will ensure less consumption and production of clean energy goods that IRA advocates say are so urgently needed to battle a destructive climate change menace. According to Politico, for example, the EV rules are “so tough that no electric vehicle on the market would qualify.” CBO estimates, in fact, only 237,000 qualifying EVs through 2026—a tiny share of projected U.S. sales. As we’ve discussed, moreover, domestic content restrictions (e.g., “Buy America” rules) have a long history of confounding federally funded projects and are all-but-certain to do similar things here.

Other harms are also likely. As George Mason University’s Tyler Cowen notes, for example, protectionist limitations on U.S. consumer subsidies will mean less production and innovation in other countries (because they’ll lose out on U.S. sales)—even ones that might have a strong comparative advantage in producing these technologies or whose companies might invent something even better than what we have here. That’s not good for a global climate challenge. Finally, local content restrictions and subsidies like these are—as the U.S. government well knows—blatantly inconsistent with various U.S. trade agreement commitments and might spark disputes with and retaliation from other countries—actions that could further undermine global production and dissemination of these (supposedly) critical climate-change-fighting technologies.

The IRA also, again, ignores other major impediments to increased domestic production of clean energy goods. Along with trade and immigration impediments similar to those for semiconductors, for example, White & Case notes that “the IRA would not address impediments arising from the complex system of US federal and state environmental laws, regulations, and permitting processes applicable to mining operations,” which experts “consider …to be the single largest impediment to expanding domestic production of critical minerals at a scale needed to support the energy transition.” Indeed, as R Street’s Devin Hartman detailed this week, “private markets are brimming with clean energy and carbon reduction appetite but cannot satisfy their hunger because of pervasive flaws in regulatory architecture.” A recent Wall Street Journal piece detailed some of this private activity:

“Despite the lack of progress by governments, businesses have continued to invest in green energy, often spurred on by demands from customers”

— Scott Lincicome (@scottlincicome) July 1, 2022

“Capital markets increasingly don’t care that governments are broken”

“It’s going to be the private sector that’s…going to drive this” pic.twitter.com/F3gGvdFU2p

Thus, our clean energy problems aren’t mainly on the demand-side (which IRA subsidies would target), they’re on the supply-side. Hartman notes, in fact, that “there are individual regulatory reforms with more emissions impact than the core energy subsidies of Build Back Better, which are largely replicated in the IRA.” Yet the IRA ignores these regulatory reforms and instead pushes subsidies — subsidies that, per Hartman, might create new problems in U.S. clean energy markets when they run into existing regulatory barriers: “Clean energy deployment is a kinked regulatory hose, and subsidies increase the pressure.”

Connecting the Dots

Subsidizing companies while also hamstringing them makes no sense until you factor in the obvious politics: Sure, these provisions might slow or even thwart supporters’ stated policy priorities of boosting U.S. tech ambitions or battling climate change, and, sure, there may be better ways to attack these very real issues; but the legislation as drafted rewards key members of Congress (especially Sen.r Joe Manchin) and core constituencies (especially labor unions), while also helping Democrats look “tough-on-China” and deliver “political victories” (and subsidy goodies) before the midterm elections. “Existential crises” are therefore subordinated to more pressing political priorities.

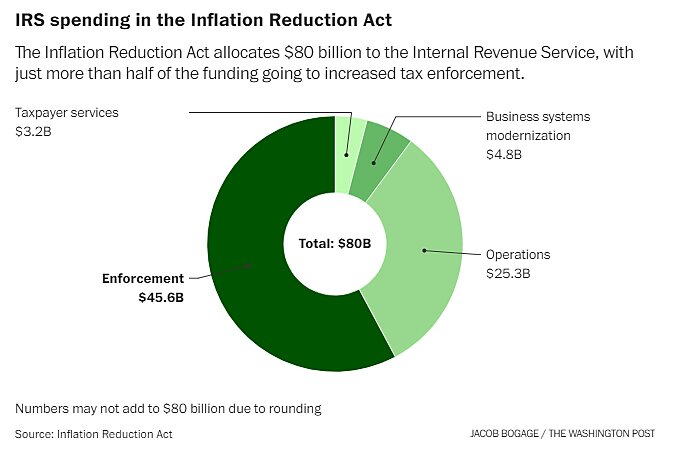

These two areas certainly aren’t the only ones suffering from this political malady: Everyone is worried these days about rising prices of food, fuel, housing, and other necessities, yet trade and immigration restrictions, ethanol mandates, agriculture programs, labor and environmental regulations (e.g., the National Environmental Policy Act), and many other bad policies—policies that nobody seems to like beyond the specific groups enriched by them—are untouched or even expanded. (For more on U.S. construction woes, I recommend this recent and frustrating piece that I included in last week’s links.) We fret about climate change and its growing costs, yet not only block certain types of renewable energy (especially if it’s made by foreigners!), but also do things like subsidize insurance for wealthy Americans in the most flood-prone areas of the country. We openly worry about China invading Taiwan and thereby destroying the global technology market, yet our speaker of the House’s recent trip there—quite obviously with November and her legacy in mind (and against the Biden administration’s wishes)—may have actually made conflict more likely (e.g., by encouraging U.S. and other foreign companies to abandon Taiwan, bolstering China’s efforts to become self-sufficient—including in semiconductors!— and giving the CCP an excuse to get even more adventurous in the Taiwan Strait. We rightly worry about tax cheats, but just throw more money at the IRS while doing nothing to actually modify its behavior or, even better, to simplify the tax code to ease compliance and enforcement (the IRA, of course, makes taxes even more complex).

Politics Corrupts

The obvious counterargument to my concerns here is that these political compromises, while admittedly ugly and inefficient, are the necessary price to get anything done in Washington these days. However, this argument fails for several reasons. First, it ignores how these political compromises can not only reduce the policies’ efficacy but actually do more long-run harm than the admittedly-messy status quo. Take the EV credits, for example: Supporters now claim that, thanks to vigorous industry lobbying, the strict origin rules will eventually be watered down in subsequent executive branch regulations, similar to how current Buy American rules allow for waivers under certain conditions. Yet, leaving aside that the planet’s supposed hopes are now in K Street’s hands (LOL), this approach to policymaking ensures further politicization, bureaucratization, uncertainty, and delay—precisely what you don’t want if you’re trying to encourage long-term investment in cutting-edge industries.

New and uncertain injections of public funds also risk crowding out or, at least, delaying private investments in targeted clean energy sectors (which, again, were already booming) or new market entrants that lack lobbying cash and regulatory expertise. The threat of new trade conflicts could do the same (especially given how loose and discretionary U.S. trade law is when it comes to imposing new tariffs). And paying for these subsidies via new taxes risks slowing growth and development elsewhere in the U.S. economy. In fact, the Tax Foundation estimates that the IRA’s new corporate taxes will slightly reduce economic growth and raise taxes on, among others, U.S. manufacturing companies (around $66 billion) that aren’t lucky enough to get subsidized.

Second, embracing politicized half-measures risks undermining future consensus on better, more lasting reforms—in the same or different areas. Large majorities seem to (quietly) agree, for example, that immigration and STEM education are essential to future U.S. technological competitiveness — not just in semiconductors or clean energy. Yet picking the low-hanging semiconductor subsidy fruit without any education or immigration reforms could eliminate what might very well have been the most potent motivation for making those needed changes. And if the omission of key reforms like these or the inclusion of political sweeteners undermines a policy’s efficacy or results in high profile failures, it’s sure to undermine public confidence in government generally and support for future (more worthwhile) proposals. Indeed, that’s precisely why the Biden administration quietly waived Buy American restrictions for last year’s infrastructure bill through this November (obviously, November):

[American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials rep Jim] Tymon said the temporary waiver DOT put into place allowed infrastructure projects that were in the planning process for years to proceed this summer. Without it, some projects faced delays. “We understand there’s kind of a chicken or egg situation here,” Tymon said. “If we’re not able to prove to America and Congress that we can get dollars out there in the community, that doesn’t bode well for us when we have to go back to Congress and push for a similar level of investment.

Yes, you read that right: We had to pause implementing the policies so we could pass more of them. Only in Washington.

If these risks sound familiar, they should. As I detailed in a paper (and summarized in this space) last year, many of these exact economic and practical problems arose the last time we embraced “green industrial policy” a decade ago in the Obama-era American Recovery and Reinvestment Act. And, as AEI’s Matt Weidinger documented earlier this week the IRA in many cases simply “revives and expands many of the same supposedly ‘transformational’ green energy initiatives in the Obama stimulus law—at far greater taxpayer expense.” So we get to enjoy that whole mess all over again—only bigger this time. Great.

(Guess I’ll have to eventually write a new paper.)

To be clear: None of this argues for simply doing nothing—about climate, China, or anything else. (Though China seems to be handling things themselves just fine these days.) But it most certainly does argue for acknowledging the limits of, and having more humility about, “transformative” federal policy: the grandiose, perfect schemes concocted in our finest planners’ minds are most certainly not what end up getting passed by Congress because actual members have competing, often overwhelming non-economic (political) priorities. These proposals also usually run smack-dab into other, pre-existing and also-politicized policies that can turn potential policy victories into big, widely-publicized losses. As a result, supposed “second-best” policies can end up doing more harm than good, wasting finite resources, and undermining political support for better policy reforms in the future. This kind of policy humility argues for government doing less, sure, but it also would help to ensure that the policies government does enact are actually effective in achieving the priorities elected officials claim to champion.

But, hey, who can think of stuff like that when they have another election to win?

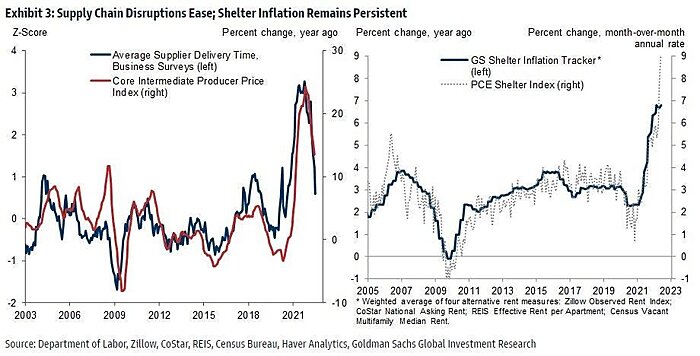

Chart(s) of the Week

Via Goldman-Sachs (no link, sorry):

The Links

The messed-up U.S. insulin market is a massive government failure

EV interest falls with gas prices

“China can’t afford to invade Taiwan”

Why is the FDA harassing distilleries that made pandemic hand sanitizer?

New England governors worried about energy prices ask Biden for Jones Act waiver

Conservatives for higher prices (no, literally, that’s what he said)

Tyson resists NY “price gouging” investigation

HHS botched U.S. monkeypox vaccine order

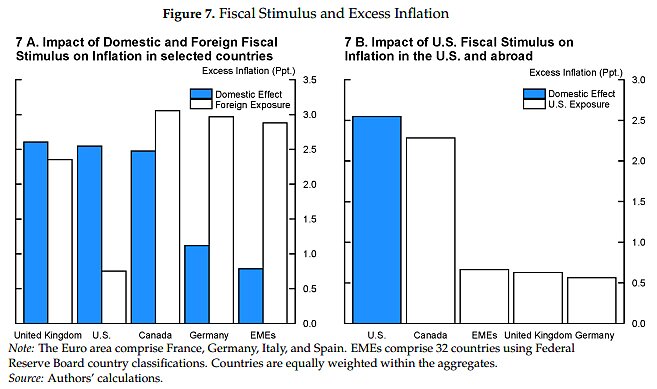

Fed paper: “generous” fiscal policy (spending) boosted inflation, especially in the USA

Legal immigrants face “sizable” barriers in U.S. labor markets, costing them and us

How Edmund Burke learned to love free markets

Home sellers are cutting prices (and iBuyers are struggling)

Photographers are abandoning Instagram and heading to rival platforms

Corruption rocks China’s industrial policy-fueled semiconductor industry (more)

On the cost of nuclear power (especially versus natural gas)

Nationalist clothing company fined for replacing Made-in-China labels with Made-in-USA ones

Food labeling confusion caused $161 billion in food waste per year