New Panic Over “Upflation”

Look out, there’s a new pricing panic in town. “Upflation,” as Bloomberg defines it, is supposedly “an attempt to create new applications for things consumers have decided they no longer need as much of — and upcharging for them” [my emphasis].

This includes products like full-body deodorant, specialty razors that reach “tricky areas,” and revamped food items such as ice cream marketed as snack bites, cereal as dinner, and Doritos as a side dish.

Bloomberg’s article suggests that this is a consequence of inflation. Rising prices and price-sensitive customers have seen certain industries struggle in sales terms, particularly in products like razors, deodorant, bread, milk, and salty snacks. In others, certain manufacturers are seeing customers shift to no-frills, cheaper options as prices rise. Having sweat “shrinkflation” as hard as they can, some businesses are thus looking for other ways to boosts profits — including revamping products to find new uses or types of output. And for some firms, it is working:

Companies say these new products are performing better than forecast, but won’t share specific sales figures. P&G’s most recent earnings report highlighted an almost two-year trend where revenue growth came from people buying fewer things at higher prices.

“So what?” you might say. Well, various policymakers have implied that firms changing product sizes or types or the way they charge is somehow illegitimate or even driving inflation. The Bloomberg article itself has a bit of that tone too. We could thus easily imagine “upflation” soon joining “shrinkflation,” “skimpflation” and “junk fees” as scare terms used by politicians to imply that greedy corporations are covertly driving high prices and so inflation.

But the truth is that upflation is just another case of companies trying to adjust to a new macroeconomic reality through entrepreneurial endeavors. If customers value the new uses and types of products, they will buy them and firms will profit. If not, the products will fail. We shouldn’t muddle this conception with that of inflation — which is a macroeconomic phenomenon driven by an imbalance between the growth of spending and production.

Stiglitz on Economists and Price Gouging

On page 126 of his new book, The Road to Freedom: Economics and the Good Society, Nobel prize-winning economist Joe Stiglitz writes:

There is common agreement, though a few economists dissent, that price gouging should be discouraged or simply not allowed, especially when it comes to essentials like life-saving drugs, home heating, or fuels.

This is simply a misrepresentation of economists’ views. Numerous Clark Center for Global Markets polls, for starters, show that economists overwhelmingly oppose regulations that constrain firms’ ability to raise prices during a publicly declared emergency.

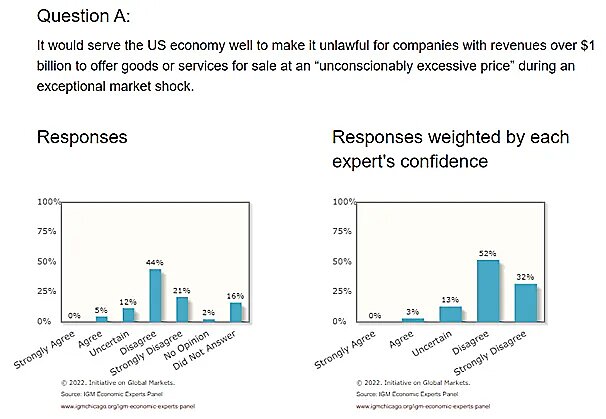

In response to a 2022 poll prompt, “It would serve the US economy well to make it unlawful for companies with revenues over $1 billion to offer goods or services for sale at an ‘unconscionably excessive price’ during an exceptional market shock,” 65 percent of economists polled disagreed or strongly disagreed, while only 5 percent agreed, with no one in strong agreement. The margin grew larger still when weighted by each expert’s confidence, with 84 percent disagreeing, as the results below show.

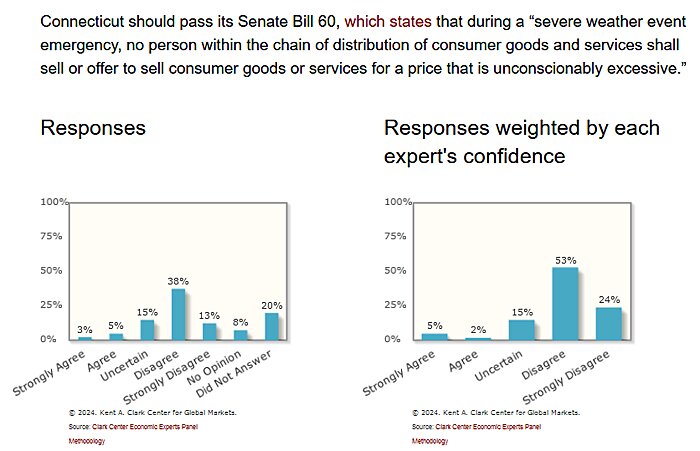

This was no anomaly. When asked about voting for a bill that would prohibit charging “unconscionably excessive” prices during a severe weather event, economists from a 2012 Clark Center poll also widely objected. Fifty one percent disagreed or strongly disagreed with the proposal, and when weighted for confidence, that figure rose to 77 percent.

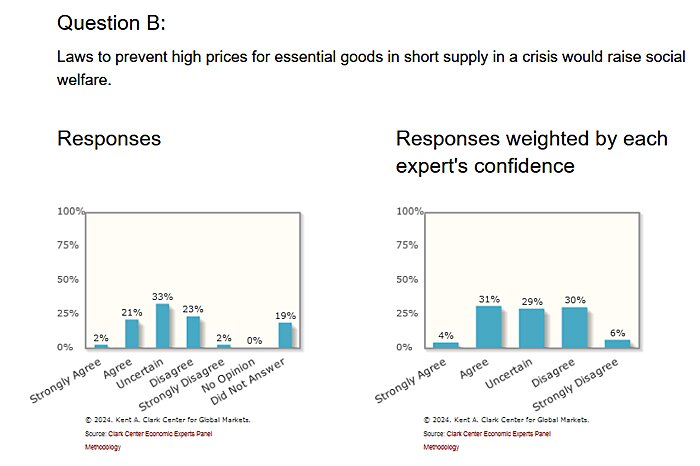

Even during the height of the pandemic, in fact, more economists than not thought that “laws to prevent high prices for essential goods in short supply in a crisis” wouldn’t raise social welfare.

Stiglitz is thus wrong in his assessment of where economists are at on “price gouging.” For more on anti-price gouging laws, see Chapter 13 of The War on Prices.

Shrinkflation Labels in France

Senator Bob Casey and President Biden want federal legislation to discourage shrinkflation. In France, it’s now a reality. Starting this month, large supermarkets must label packaged products that are resized downwards. Non-compliance can result in fines of €3,000 for individuals (such as store managers) and up to €15,000 for corporations. Finance Minister Bruno Le Maire stated that the measure aims to rebuild consumer trust through transparency. Yet store owners are livid that they, rather than the manufacturers, are being held responsible for disclosing changes to product sizes.

We’ve written before that government attempts to prevent shrinkflation are misguided. Competition disciplines businesses on pricing, and firms are constrained by customers’ willingness and ability to pay. The recent shrinkflation was part symptom of the high inflation we’ve seen and part a return to a pre-pandemic trend of resizing.

Certain businesses just judge that their customers are more price-sensitive than quantity-sensitive. Trying to ban or deter adjusting by quantity rather than price thus means firms are more likely to adjust by price, which can hurt lower income customers in particular — it doesn’t change the macroeconomic fundamentals. In the longer term, of course, anti-shrinkflation legislation is likely to see firms simply introduce new resized and slightly rebranded versions of products over time and adjust their contracts for volumes with stores.

Housing Market Policy Mistakes in California

This week, Judge Glock had a good piece on housing woes in California. He explains how, beyond rent control, California has placed numerous other regulatory constraints on landlords which are worsening the availability of rentable housing by restricting its supply.

Landlords must have “just causes” for evictions for certain units and face potential lawsuits for up to three times any “damages” and attorneys’ fees when they improperly terminate a lease. Recent laws against housing voucher discrimination and the capping of security deposits further raise tenant and financial risks for landlords. Eviction delays are compounded by jury trials, and oftentimes landlords have to actually remove squatters on their own.

These factors combined have tilted the scales towards tenants and disincentivized landlords by raising the risks of renting their properties, thus contributing to fewer rental properties being available and unaffordable rents throughout the state.

Chapter 8 of The War on Prices has more on the pitfalls of rental regulations.