Dear Capitolisters,

Two Saturdays ago, right after my daughter’s school year began, we learned that one of her classmates tested positive for COVID-19. (Fortunately, the student was not seriously ill.) The initial informal notice was followed by a more formal one Sunday afternoon about the school’s COVID-19 protocols for this situation, in particular whether our daughter was—per the CDC guidelines and internal school procedures—in sufficiently close contact with the infected student to require testing or quarantine. Turns out, we were in the clear, and nothing more was required at that time. However, being a diligent (read: Type‑A) parent—and not feeling super-hot myself after a lot of August travel—I started looking online Sunday morning for how to get tested quickly. The search results weren’t exactly reassuring: appointments for either a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test or antigen test within a 10-mile radius of home were extremely limited. So I next started Googling for an at-home “rapid” test; luckily, I found some in stock at a nearby CVS and rushed out to grab them. Since there were only a handful on the mostly bare shelves, I grabbed a couple two-packs, paid almost $60, and went home to run the tests.

The good news is that both my daughter and I tested negative and have remained asymptomatic. She went to school all last week, and life at the homestead has been pretty normal. Crisis averted.

The bad news, however, is just how difficult this all was at this stage of the pandemic—more than 18 months after it began in earnest here. And it says a lot about not only our still-weak testing regime but also the systemic regulatory problems that all but ensure it.

America’s Dearth of At-Home COVID-19 Tests

Since mid-2020, several companies have produced rapid self-tests to detect a COVID-19 infection, but the FDA refused to approve them last year because—as my colleague Ryan Bourne explained in his recent book, Economics in One Virus—the agency’s “regulations … demanded similarly high accuracy for these tests to standard [PCR] tests,” which were highly accurate but took several days (and a lab) to complete. At that time, the antigen tests’ sensitivity and accuracy was relatively low compared to the PCR tests, so the FDA wouldn’t approve them out of concern for “false negatives” (people with COVID-19 getting a negative test result and then going out and potentially infecting others). None of this ever made any sense from a statistical and theoretical level, as George Mason’s Alex Tabarrok explained last year:

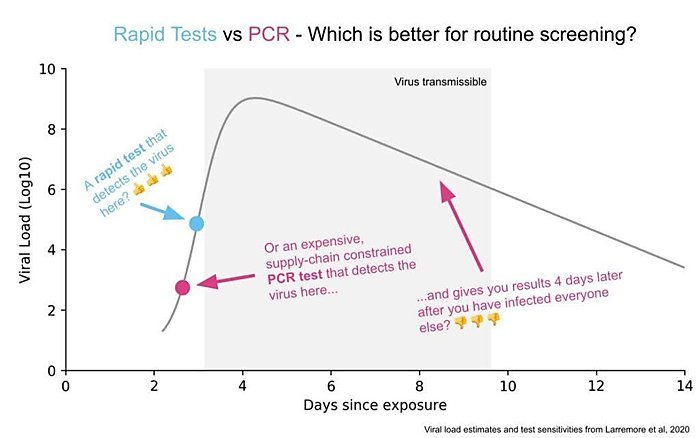

The PCR tests can discover virus at significantly lower concentration levels than the cheap tests but that extra sensitivity doesn’t matter much in practice. Why not? First, at the lowest levels that the PCR test can detect, the person tested probably isn’t infectious. The cheap test is better at telling whether you are infectious than whether you are infected but the former is what we need to know to open schools and workplaces. Second, the virus grows so quickly that the time period in which the PCR tests outperforms the cheap test is as little as a day or two. Third, the PCR tests are taking days or even a week or more to report which means the results are significantly outdated and less actionable by the time they are reported.

Tabarrok went on to explain that the proper comparison wasn’t a single antigen versus a single PCR test but comparing “test regimes” (e.g., seven strip tests at $5 each taken over a week versus one $35 PCR test). In this framework, subsequently provided in chart form below, “it’s hard to come up with a scenario in which infrequent, slow, and expensive but very sensitive is better than frequent, fast, and cheap but less sensitive.”

Tabarrok and Bourne surely weren’t alone in championing rapid tests back then: They were joined by numerous other economists (such as Nobel laureate Paul Romer in March 2020!) and public health experts (such as Harvard’s Michael Mina), all of whom understood—and wrote constantly!—that quick home testing was a critical way to control COVID-19 and let people get back to relative normalcy.

And they’ve all been proven right. We now have plenty of research and real-world examples showing rapid antigen testing, if performed regularly, is just as effective as the theorists claimed more than a year ago—and, importantly—just as effective as the PCR tests approved early on by the FDA. The tests have also evolved to be more sensitive and accurate: Mina’s team estimates, for example, that the new tests’ specificity—confirmed in multiple tests of thousands of cases—is more than 99 percent.

Yet, despite all of this, the FDA didn’t first issue an emergency approval for an over-the-counter, at-home rapid test until mid-December 2020—and that Australian-made Ellume test was available only in extremely limited quantities (and required a smartphone app to use!). Since then, the FDA has approved only five more, bringing the grand total of approved at-home antigen tests in the United States to a whopping six: Ellume; Abbott Labs’ BinaxNOW; Quidel’s QuickVue; OraSure’s Intelliswab; Access Bio’s CareStart; and Becton Dickinson’s BD Veritor. Really, though, we have just three at-home antigen tests right now because, as the Wall Street Journal reported, the last three listed above were approved only recently and thus aren’t yet on the market here. (The final two were approved last week!)

This dearth of home tests is not for lack of companies trying: Public health expert Dr. Eric Topol stated in February of this year that there were more than 30 different rapid home tests sitting at the FDA awaiting approval—some since April 2020! Furthermore, other jurisdictions have approved dozens of tests: Germany, for example, has authorized more than 60 self-tests from producers all over the world—including several made in the United States and approved for export only.

The FDA’s restrictions on the domestic supply of at-home rapid tests has had unsurprising (albeit still depressing) results—home test kits are not ubiquitous; prices are relatively high (at least $20 for a two-pack); and, given the first and second issues, they’re not very widely used. Back in Germany, by contrast, they’re available basically everywhere and cost less than a buck per test:

Talk to people in Israel, the U.K. or elsewhere in Europe, and you’ll find many places practically giving away strip tests—often subsidized by the government as part of its broader public health efforts. (As Bourne calculates in his book, the budgetary cost is low compared to the economic benefit.)

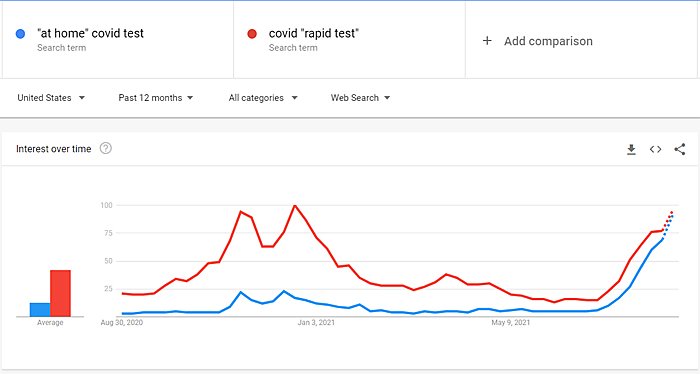

Here, not so much. And the United States’ clear lack of “testing abundance” may now be moving from regulatory embarrassment to real problem. In particular, the combination of the Delta variant’s heightened transmissibility, the start of the school year, and many workplaces ending full-time remote work has spiked interest in and demand for rapid tests that people—vaccinated or not—can use to check themselves and their kids to meet private or public protocols like the ones at my daughter’s school:

And that demand may be outstripping the supply of approved rapid tests. Last week, for example, CVS began to limit in-store purchases, and the Journal reported that approved suppliers and are struggling to keep up:

Abbott Laboratories said it expects supplies of its at-home test to be limited in the next few weeks as it hires workers and reboots factory lines that were slowed or idled earlier this summer. Availability on Amazon.com of Abbott’s BinaxNOW test and a similar test made by Quidel Corp. has been spotty, and an at-home test made by Ellume USA LLC was out of stock as of Wednesday. …

An at-home molecular test made by Lucira Health Inc. LHDX ‑2.82% is out of stock on the company’s website. A company spokesman said Lucira is boosting production.

Shortly thereafter, both Amazon and Walmart (online) went from low inventory to out of stock entirely, though they have since replenished their supplies and offer delivery in a few days. (Not exactly a “rapid” test, but better than nothing.) Many other online retailers are in a similar boat. And there various anecdotal reports of local drugstore shelves being bare:

Wanted to get some at-home rapid tests before school starts on Monday, but everyone is out (including Amazon) while my understanding is that in Europe they have multiple approved vendors and they sell for less than $1 a pop.

— Matthew Yglesias (@mattyglesias) August 28, 2021

Update: local Walgreens in Arkansas is out of tests too

— Jeremy Horpedahl 🍞🔕 (@jmhorp) August 15, 2021

(No personal need for us, just reporting from the field) https://t.co/aFJnYq3KGz pic.twitter.com/klTLHUAfFt

The good news is that, as of this writing, it appears that most people can still get a rapid self-test if they really need it, but doing so will probably come at some expense (time, money, travel, etc.)—precisely what you don’t want when the need arises.

And schools and workplaces are just now reopening.

Hopefully, we’ll avoid a serious crunch here because production is increasing or Delta is starting to wane. But it’s ridiculous that we should’ve ever been put in this situation—one that testing advocates were warning about earlier this year, even as vaccines became abundant and the virus looked to be behind us. Mina, for example, wrote in late May that “we still need widespread rapid testing even with vaccines” because of the potential for new, more potent variants, waning vaccine immunity, and potential outbreaks as fall arrives and people resume their normal lives (traveling more, masking less, going back to work or school, etc.). Tabarrok said pretty much the same thing a week later—long before Delta was raging here and in plenty of time for the FDA to get moving.

Yet here we are (and may be again in a few months).

It’s Not Just Rapid Tests

If the FDA’s longstanding (at this point) resistance to COVID-19 rapid tests were its only significant mistake during the pandemic, then perhaps we could cut them and the rest of the United States’ public health bureaucracy some slack. Unfortunately, that’s not the case—far from it. Instead, the last 18 months are littered with examples of how the bureaucracy has thwarted reasonable efforts to put the pandemic behind us. This includes:

-

The FDA’s and CDC’s initial bungling of laboratory testing protocols, which, as Bourne details at length in his book, actually inhibited the proliferation of widespread testing based on a bizarre FDA demand for a higher level of efficacy than in non-emergency times. (“Unbelievably, working diagnostic tests developed in the United States were being used in Sierra Leone before the FDA allowed them to be used here.”)

-

The FDA’s slow-walking the vaccines’ early trials, emergency use authorizations (for adults and children), and eventual “full” approvals, with the first two substantially delaying the U.S. vaccine rollouts and the latter fueling vaccine skepticism and delaying private mandates (in the face of the most robust real-world dataset ever assembled and the delta variant gaining steam).

-

The many issues with the initial, overly bureaucratic vaccine rollout last December, which I detailed at length in an earlier post.

-

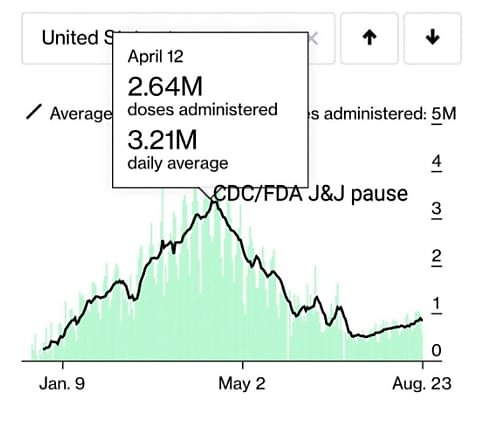

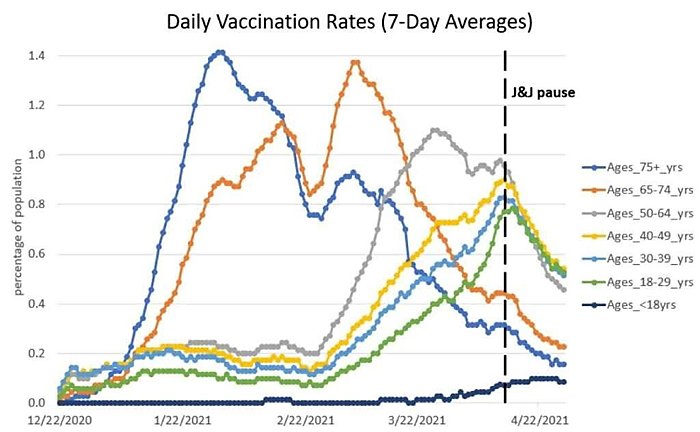

The CDC’s kneejerk pause of the Johnson & Johnson vaccine because of a very remote health risk (one far less risky than actually getting COVID-19!), which—based on the charts below and numerous anecdotes—may have stifled vaccine uptake in the United States (though survey data are admittedly mixed).

Maybe instead of trying to heroically interpret ambiguous survey data, we should look directly at the variable of interest: how many people are getting vaccinated. It underwent a huge nonlinear plunge timed *exactly* to the J&J pause and has never recovered (see below). https://t.co/1udbR60z21 pic.twitter.com/pC7OhdVq1h

— Nate Silver (@NateSilver538) May 7, 2021

And these are just the biggest (in my opinion) mistakes; as the Progressive Policy Institute’s Alec Stapp and others noted on Twitter last week, there are plenty of others across essentially the entire range of U.S. pandemic response.

While these problems vary, however, most of them stem from the same systemic failures within the American public health bureaucracy. Doctor and writer Scott Alexander dug deep into these issues in a recent (and well worth your time) piece, focused primarily on the FDA and chock-full of depressing anecdotal support. His diagnosis (ha), like so many others, really boils down to one thing: The agencies are—by their very mandates—far too unwilling to take a risky action even though the risks of inaction are clearly far higher. (Alexander describes the FDA’s mandate as “approve drugs that definitely work, reject ones that are unsafe/ineffective, expect people to freak out and demand your head if any unsafe/ineffective drug gets through, nobody will care no matter how many lifesaving treatments you delay or stifle outright.”)

This is a classic “trolley problem” scenario, in which an individual faces the tough choice of letting a trolley stay its current course and run over many people or pulling a switch and saving those folks but definitely running over (and thus being directly responsible for harming) one other person. Except in the case of the American bureaucracy, the switch is basically hardwired to stay unpulled in the absence of a ton of time, money, and paperwork (and even then, maybe not).

Thus, we have a public health system full of insanely technocratic rules, mainly developed for non-pandemic times, that demand near-perfection in times of crisis instead of maximizing overall benefits based on real-world needs, constraints, and tradeoffs. Throw some John Nestors into the mix, and it’s a system effectively designed to generate the problems above (and many others).

So What Can Be Done?

As Alexander then notes, the U.S. public health bureaucracy’s systemic problems are really problems with the United States more broadly:

And it’s hard to even blame the people who set the FDA’s mandate. They’re also doing the best they can given what kind of country/what kind of people we are. If some politician ever stopped fighting the Global War On Terror, then eventually some Saudi with a fertilizer bomb would slip through and kill ~5 people. And then everyone would tar and feather the politician who dared relax our vigilance, and we would all restart the Global War On Terror twice as hard, and drone strike twice as many weddings. This is true even if the War on Terror itself has an arbitrary cost in people killed / money spent / freedoms lost. The FDA mandate is set the same way — we’re open to paying limitless costs, as long as it lets us avoid a very specific kind of scandal which the media will turn into 24–7 humiliation of whoever let it happen. If I were a politician operating under these constraints, I’m not sure I could do any better.

This is precisely what I meant back in January when I lamented that American citizens, politicians, and media would likely have freaked out at a “market-based approach that simply auctioned off doses to the highest bidders and let anyone get an untested jab,” even though that system may have been “theoretically more effective in encouraging production and distribution (and thus in eliminating the virus).” As my Cato colleague Dr. Jeff Singer convincingly argued back in April, there are plenty of good reasons for root-and-branch reform of the current system, but I do doubt whether most of the polity would go along—at least not quickly.

Given these practical considerations, Alexander—and then economist John Cochrane responding to him—suggests a few “small” fixes to the current system to produce better outcomes while acknowledging our current societal limitations, including: (1) rewiring (“unbundling”) the FDA approval process to distinguish between doctors’ being allowed to prescribe a drug and insurance (public or private) being required to cover it; (2) the FDA only providing information about safety and efficacy instead of making a “yes/no” ruling on those issues (and trying to divine and manage public psychology in the process); and (3) changing the FDA’s incentive structure by linking its budget to drug approvals. All interesting and worth considering.

For my money, however, the easiest fix to the current system is one they didn’t mention: reciprocity. In particular, the United States government should immediately approve (and allow the importation of) any medical good—drugs, tests, medical devices, PPE, etc.—that has been approved by the regulatory body of another major, developed country like Germany. Doing so wouldn’t require a major rewiring of the bureaucracy (via complex and lengthy rulemaking) but would achieve at least three benefits over the current system. Most obviously, it would accelerate Americans’ ability to access critical, often life-saving drugs and other goods that, for whatever reason, our public health bureaucracy won’t timely approve. Second, it would let globalization do its thing: encouraging more production of essential medical goods to meet latent U.S. demand and easing domestic production bottlenecks during national emergencies. It’d sure be nice, for example, if we could import a bunch of those deeply discounted strip tests from Germany while U.S. factories crank up again. Finally, reciprocity might accelerate U.S. regulatory action, either by giving risk-averse bureaucrats political cover or just embarrassing them into moving more quickly. For these and other reasons, a wide range of economists and health experts support medical reciprocity, and, as Singer noted back in April, there’s even legislation in Congress—the Reciprocity Ensures Streamlined Use of Lifesaving Treatments (RESULT) Act—to get the ball rolling.

In the meantime, however, you might want to stock up on a few rapid tests.

Postscript

Amazingly enough, just as I was finishing off this column, we learned that two top FDA officials will leave their positions this fall because they were upset that the White House was moving too fast on announcing vaccine booster shots. As one report put it, “[t]he Biden administration has made clear that its priority, when it comes to boosters, is to stay ahead of the virus. But in doing so, it’s also getting ahead of the process by which such decisions are usually made.”

That “process” is very much the problem.

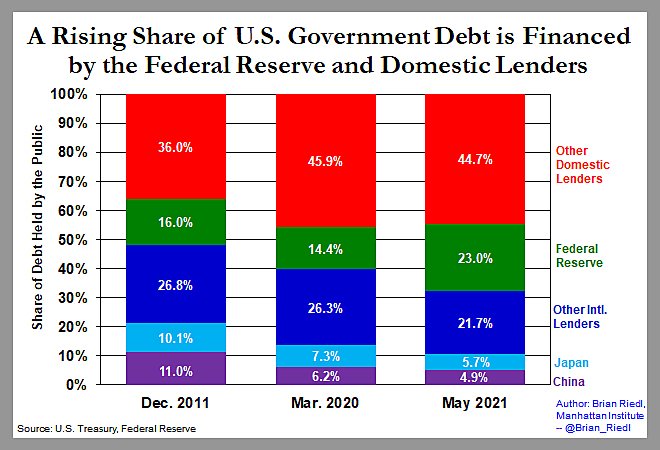

Chart(s) of the Week

(Source)

The Links

Alfredo Obregon and I talk about tariffs and the “shipping crisis”

How state regulations (“certificate of need”) laws limit ICU beds and worsen the pandemic

Can libertarians support vaccine mandates?

Dollar General getting into rural health care

Colorado Gov. (D) Jared Polis: the state’s income tax “should be zero”

The legacy of 9/11 for U.S. immigration policy

“How a federal agency is blocking America’s largest wind farm”

“Lack of a Vaccine Mandate Becomes Competitive Advantage in Hospital Staffing Wars”

China limiting kids’ screentime

“There’s just not enough metal inside of North America”

Swedish rent control still not working