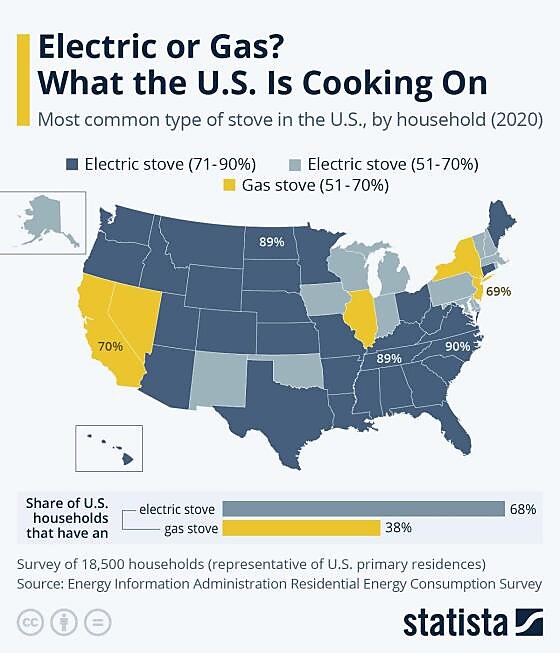

Judging from the widespread reaction to each proposal online, you’d be forgiven for thinking that both bans were total no-brainers and that opposition came from only cranks and cronies. Non-competes, we were told, do serious and widespread damage to all American workers’ wages and mobility, are never entered into legitimately, and provide absolutely no economic benefits. Anyone skeptical of a total ban thus is just a bootlicking conservative shill for Big Employer. Gas stoves, on the other hand, give millions of American children asthma, promote dirty, rotten fossil fuel consumption, and are totally inferior to new electric induction ranges. Skeptics are just baby-hating, foodie-poseurs and right-wing culture warriors who… as Jonah documented a few days ago, totally made the whole thing up anyway?

And both bans are clearly and obviously justified by reams of academic literature and current federal law. Obviously.

Yet even a cursory dig into both cases reveals problems with these narratives and provides a handy framework, I think, about how to think about any prohibitionist proposal in the future—whether you’re a zany libertarian like me or just a regular reader of (ahem) really long, chart-filled newsletters.

Prohibitionist Weaknesses Abound …

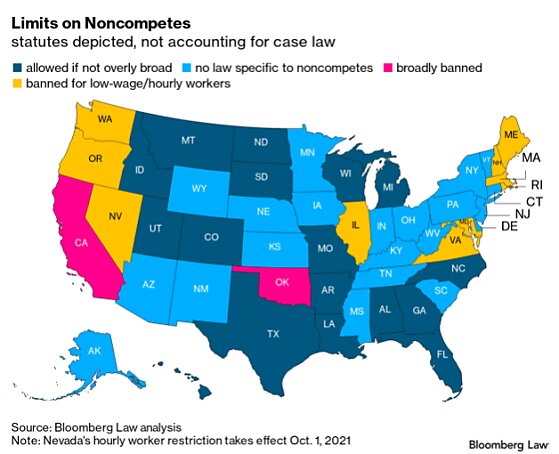

There are, of course, significant differences between non-compete agreements and gas stoves, their effects, the agencies regulating them, the underlying laws at issue, and so on. But in both proposals to ban them, we see a lot of the same warning signs—signs that argue strongly against a quick ban and for just a smidge more humility about the proper federal policy response.

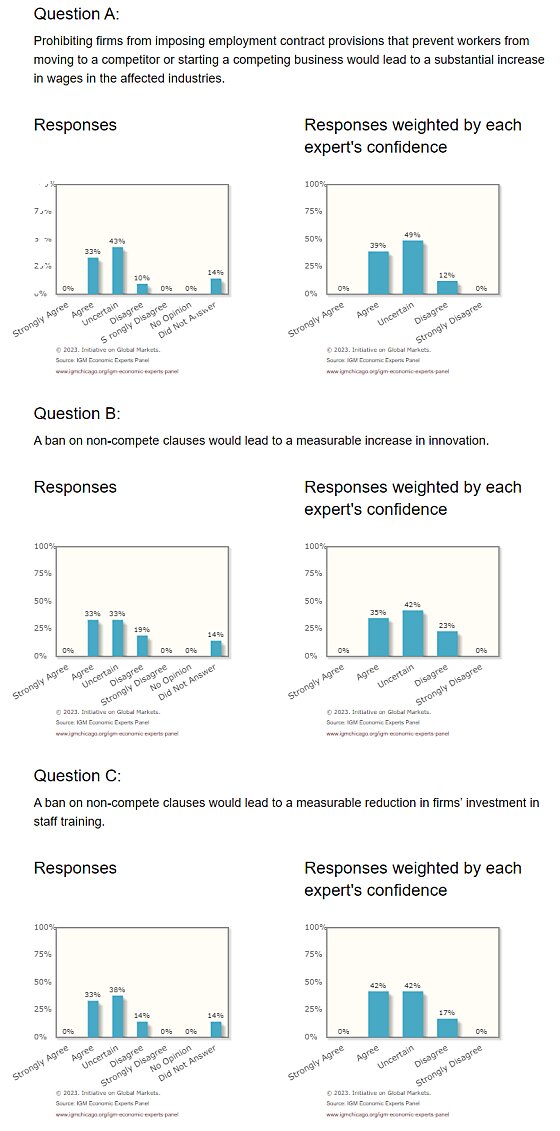

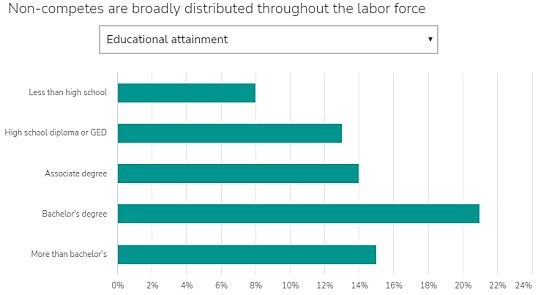

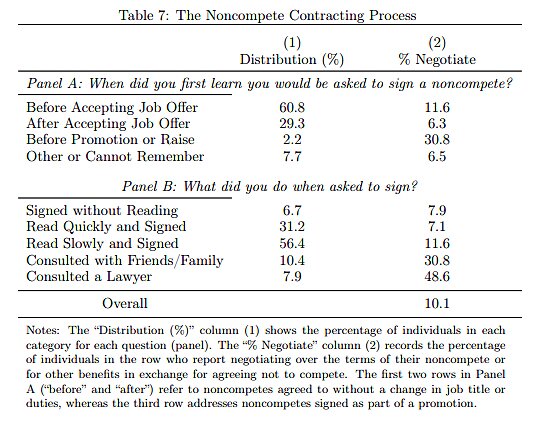

First, the literature on non-competes and gas stoves is not nearly as clear-cut and ironclad than what you probably heard online. For example, economist Brian Albrecht went through various studies showing the harms of non-competes and found the research to be of good quality but new, thin, and nuanced—not definitive. It looked at only specific states (Oregon and Hawaii, for example), found correlation (not causation), and applied only to certain classes of workers (e.g., those earning hourly wages or CEOs) or types of companies (e.g., publicly traded ones). He cautions that, hey, maybe a near-total-and-retroactive national ban isn’t in order when you have a grand total of one paper doing a broader “welfare” analysis of non-competes (i.e., assessing net costs/benefits after all tradeoffs are considered), especially when it too has some of the aforementioned limitations. Other wonks—though they’re certainly in the public minority here—have raised similar concerns, and Albrecht points us to a brand new poll of leading economists showing significant disagreement and uncertainty about non-competes and how banning them would affect wages, innovation, and job training.