Is the American Dream in peril? Collectivists say yes and point to rising inequality of income. But they don’t understand the question. A commitment to equality of outcomes in life is totally alien to the American ethos. In the words of Abraham Lincoln, America is committed to “an open field and a fair chance for your industry, enterprise and intelligence.” Recognizing that, in the words of Will Durant, “freedom and equality are sworn and everlasting enemies and when one prevails the other dies,” America has always chosen freedom.

The American Dream is of individual upward mobility, not social progress toward uniformity. Analysts for the Pew Charitable Trusts in 2012 quantified the economic advancement of American families. They compared the inflation-adjusted income of parents with that of their children some 30 years later. (The parents in the study were 41 years old on average and the children 45 when their incomes were measured.)

Measured by inflation-adjusted household income, 93% of children who grew up the bottom income quintile were better off than their parents. Of children in the middle three-fifths, 86% grew up to live in families with higher incomes than their parents. Even among those in the top income quintile, 70% were better off.

This upward mobility across all income classifications was possible because of the growth of the American economy. Over the 35 years of the study, real median family income rose by 89%. This American cornucopia was spread across the entire income distribution—with the exception of the prime work-age adults in the bottom quintile who dropped out of the workforce as government transfer payments exploded beginning in the mid-1960s. They benefited from the growth in transfer payments, but their ability to rise further was stunted by the incentive not to work.

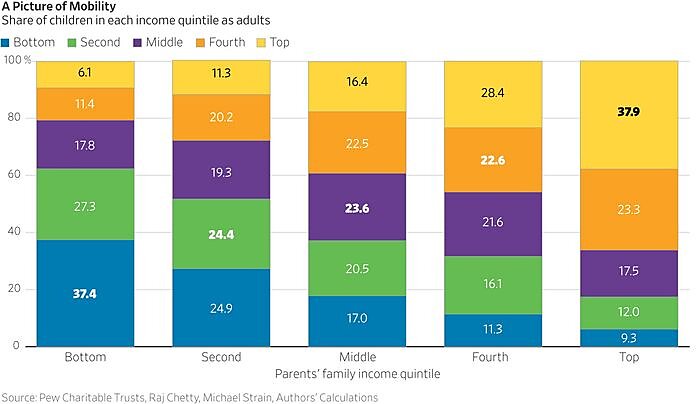

Without accounting for this overall income growth, three independent research efforts have measured relative mobility—the extent to which children reared in families in one income quintile stayed in the same income quintile, rose to a higher quintile, or fell to a lower quintile. The first, an extension of the Pew Charitable Trusts study cited above, looked at parental income from 1967–71, when the children were younger than 18, and 2000-08 when the children were 32 to 58.

The second study, by Raj Chetty of Harvard, looked at parental income from 1996–2000, when children were 15 to 20, and adult children’s income in 2011-12, when the children were in their early 30s. The final study, by Michael Strain of the American Enterprise Institute, compared the income of children who were in their 40s in 2013–17 with that of their parents in their 40s.

Since the findings of these three studies covering the past half-century were extraordinarily similar, we have averaged them in the nearby chart. For each parental income quintile, the chart shows the percentage of adult children from those families who grew up to live in each income quintile.

You might expect that children would tend to end up in the same income quintile as their parents. Parents impart their genes and values to their children. Those with high incomes are generally highly educated and give their children every advantage, such as private schools, tutors and counselors. Poor families often lack the knowledge and resources to provide those advantages.

Yet the share of adult children who grow up to live in a household in the same income quintile as their parents is surprisingly small. The chart shows that for the middle three quintiles, only 22.6% to 24.4% of children remain in their parents’ quintile—barely more than the 20% that would result if income quintiles were assigned at random. On average, 39% of those children as adults rose to a higher quintile and 37% fell to a lower one. The harshest critics of mobility in America can find little to fault in the income mobility of the three central quintiles.

They focus instead on the top and bottom quintiles—but miss substantial mobility there too. Of children reared in the top quintile, 62% fell to one of the lower quintiles, including more than 9% to the bottom quintile. A significant number of the children reared in the top quintile who stayed in the top quintile as adults had incomes far greater than their parents, but statistically they could not rise out of the top quintile.

With few advantages and often trapped in failing public schools, 63% of children who grew up in bottom quintile families rose to a higher quintile, 6.1% rising all the way to the top quintile. A significant number of those who failed to rise would have been the adult children who didn’t work as public assistance soared. The share of the bottom quintile who worked fell from 68% in the parents’ generation to 36% in the children’s generation.

But even these impressive numbers understate real income mobility in America. These studies measure relative mobility by comparing the children’s income quintile then and now. Relative mobility is a zero-sum game—by definition, 20% of households are in the lowest quintile and only 20% in the highest—but income growth isn’t. The vast majority of adult children had higher real incomes than their parents. To rise out of the bottom quintile, children’s inflation-adjusted income had to increase by more than the growth of the income ceiling for the bottom quintile during the years between generations—35% in Mr. Strain’s study. Children reared in any other quintile had to see their real income as adults rise on average by roughly 50% above their parents’ income simply to avoid falling into a lower quintile than their parents. The climb to a higher quintile is steeper still.

Fortunately, data from the Strain study can be used to measure mobility in a way that takes into account the extraordinary income growth in America between the parents’ generation and the adult children’s generation. When the income of the children is compared with the inflation-adjusted income of their parents using the real income quintiles of their childhood in 1982–86 rather than the income quintiles of 2013–17, measured mobility is dramatically greater. Only 28% of children reared in the bottom quintile had adult incomes that would put them in the bottom childhood quintile, and 26% rose all the way to the childhood top quintile, which required a minimum income of only $111,416 (in 2016 dollars) for a family of four in 1982–86. A family of four with that income in 2013–17 would have been in the middle quintile based on 2013–17 income distribution.

During the 35 years of the study, adult children who worked rode up the American economic escalator as average incomes rose dramatically. Those who climbed as the escalator rose moved up faster. Those who stood still or stumbled down rose more slowly, and those who stayed off the escalator by not working missed the ride. The mobility studies shown in the chart capture the effect of climbing, stumbling and choosing not to ride, but they miss the escalator effect, which came from the growth of the American economy. Many of today’s middle-income adults have a real standard of living that would have put them in the top quintile in their parents’ era.

This incredible income mobility is measured only over one generation. Parents struggle and sacrifice to provide their children with education and opportunities they themselves lacked. Millions of parents have lived out their dreams through the achievements of their children, generation after generation. As a result, America’s real mobility is most visible over multiple generations. Many historians believe George Washington’s grandmother came to America as an indentured worker. Washington became one of the richest men in colonial America and, in the words of King George III, “the greatest man in the world.”

It is better to be born rich, brilliant and beautiful, but poor, ordinary and homely people succeed in America every day. The American dream is alive and well.