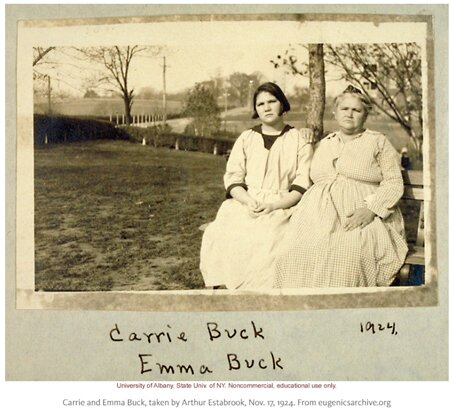

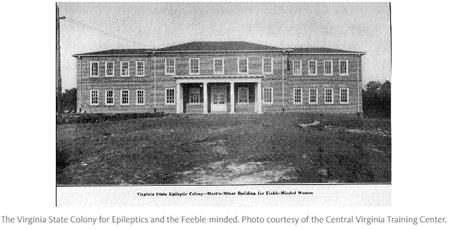

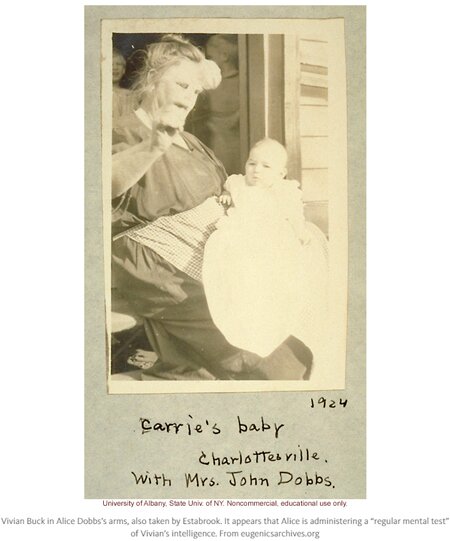

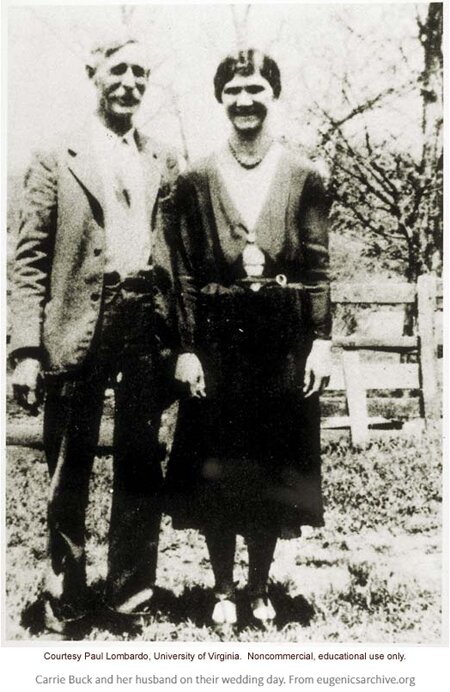

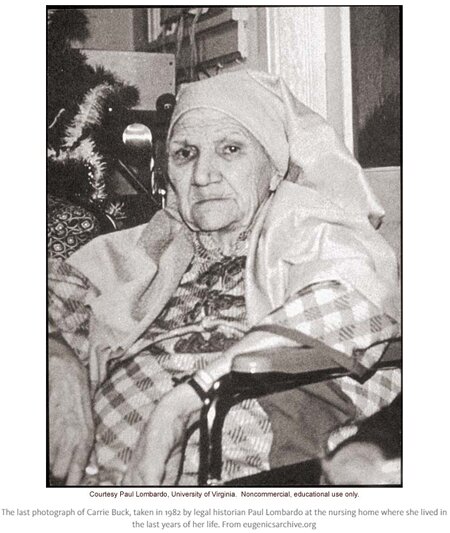

Carrie Buck was an average, unassuming girl who grew up around Charlottesville. She wasn't very smart, but she wasn't dumb either. She didn't come from the best circumstances, but she did the best with what she had. Pictures show a plain young woman with short, dark hair, bobbed in the fashion of the time. In one photo, taken by Arthur Estabrook, an "expert" in eugenics whose testimony would help seal her fate, Carrie sits on a bench with her mother Emma at the Virginia State Colony for Epileptics and Feeble-minded, where both were institutionalized.

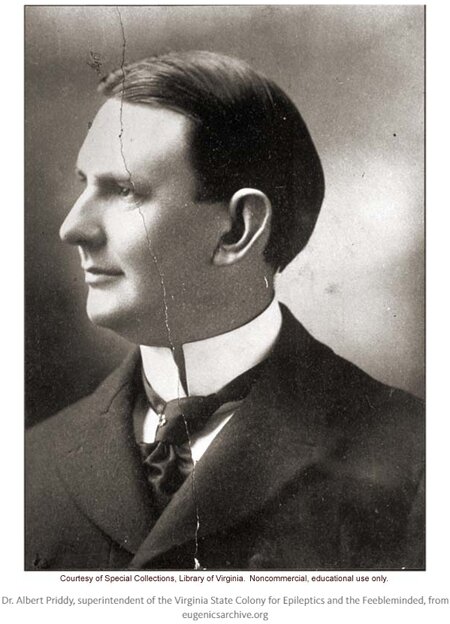

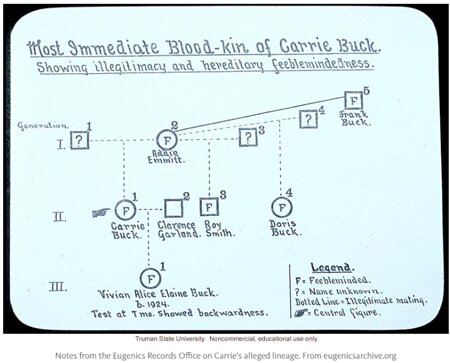

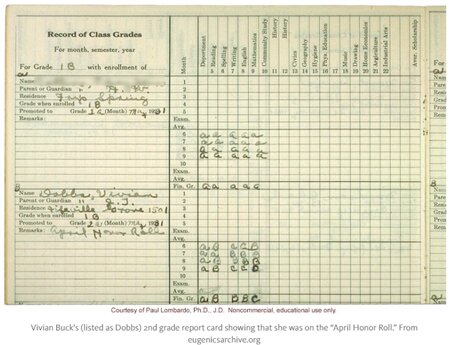

Estabrook's photo of Carrie and Emma was taken on November 17th, 1924, the day before Carrie's trial began. Estabrook had come to visit Carrie and Emma at the urging of Dr. Albert Priddy, the superintendent of the Virginia Colony. Priddy was building a case against Carrie, a case for her forced sterilization, and he needed a purported expert in the "science" of "inferior genetics" a.k.a. eugenics to testify that Carrie, her mother, and Carrie's six-month-old daughter Vivian were all congenitally and irredeemably "feeble-minded."

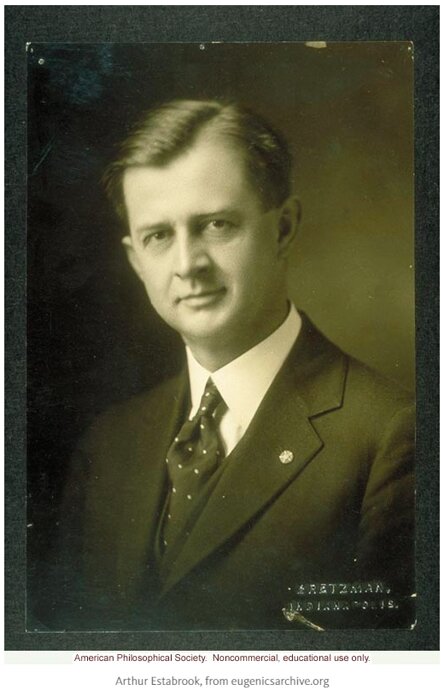

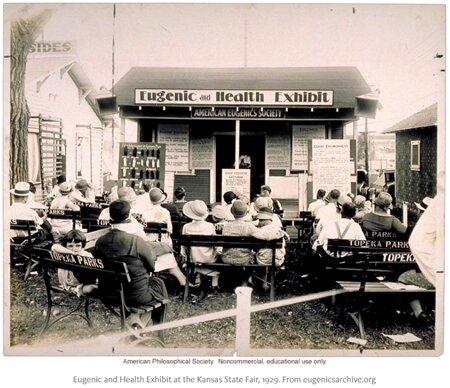

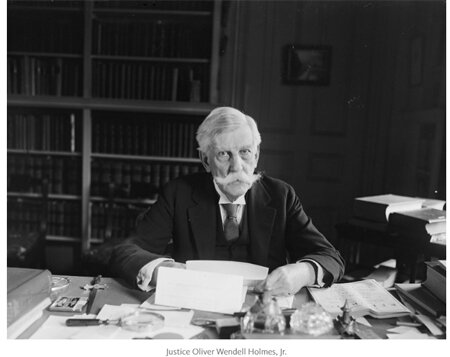

In a different time, Estabrook, with his neatly parted hair and defined features, could have become a well-known character actor, a face "in all those movies." But Estabrook was employee at the Eugenics Record Office in Cold Spring Harbor, New York, and he was more than prepared to testify to the inferiority of Carrie and her bloodline. Most of his life had been devoted to diagnosing and describing "defective bloodlines" that, in his view, held humanity back. At the urging of Aubrey Strode, the lawyer for Dr. Priddy and the Virginia State Colony, Estabrook rushed down to Lynchburg to testify against Carrie. Strode believed that the testimony of a true expert in eugenics would be crucial to developing an unassailable legal record proving that Carrie, Emma, and Vivian all carried defective genes and, therefore, that the state had both the authority and the right to sterilize Carrie to prevent any further "feeble-minded" offspring. He needed such expert testimony if the appellate courts, and possibly even the U.S. Supreme Court, were going to uphold Carrie's sterilization and thus ratify not only Dr. Priddy's plans for the mass sterilization of "genetic defectives," but also the plans of thousands of similar eugenicists around the country. Eugenics was Estabrook's life work, so of course he came as quickly as he could.

It only took Estabrook a short time to be convinced that Carrie and Emma were hereditarily "feeble-minded." In the picture he took, Carrie and Emma stare distantly at Estabrook's camera, seemingly not too happy to have been interrogated by someone who presumed they were imbeciles from the outset.

We know Carrie's story because her case eventually made it to the Supreme Court. But to the Commonwealth of Virginia in the 1920s, Carrie was just another congenitally "feeble-minded" woman who, in the parlance of the times, had a tainted "germ plasm" that would create generations of "socially inadequate defectives" if she were allowed to procreate freely. Carrie is the most famous of the at least 60,000 Americans who were forcibly sterilized in order to "cleanse the race" of undesirable genes.

The United States forcibly sterilized people through the 1970s. Many victims are still living. Virginia has apologized for its sterilization program, and, like North Carolina before it, voted to compensate still-living victims.

Yet, even today, many law professors seem to want to sweep Buck v. Bell under the rug. They'd rather talk about Lochner v. New York when the Court overturned New York's maximum work hour law as a violation of the liberty of contract than Buck v. Bell. Judges are still said to be "Lochnerizing" when they are accused of legislating from the bench, but we don't have a similar adjective form of Buck. Furthermore, because Lochner was overturned during the New Deal, its residual impact on our laws has been minimal. Buck v. Bell's legacy is far bloodier.

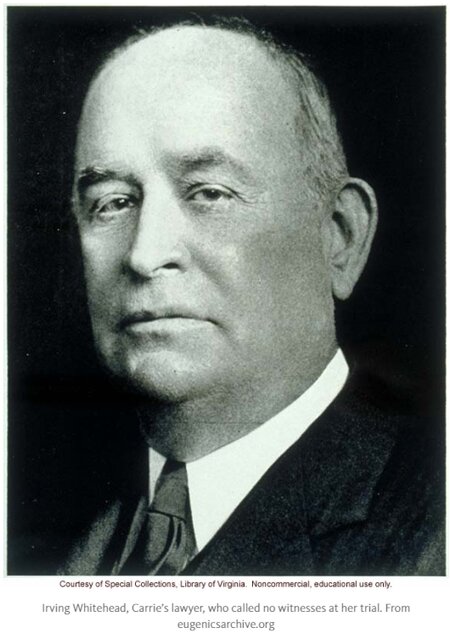

Even for those familiar with the general facts of Buck v. Bell, Carrie's story is worse than they realize. We now know that she was unknowingly a part of a plot to validate Virginia's forced sterilization law, passed in 1924 to rid society of "idiocy, imbecility, feeble-mindedness or epilepsy." Even Carrie's lawyer was a part of the plot, offering essentially no defense to the groundless claim that she was congenitally stupid. The simple but far from stupid girl from Charlottesville found herself at the center of what amounted to a conspiracy against her own reproductive future.

The judges and justices who ratified Carrie's sterilization abdicated their responsibility to protect the weakest among us from the machinations of the powerful and the prejudices of the majority. Carrie needed protection from pseudoscience and groundless assertions, but all she got was an unquestioned seal of approval.