I’m talking about digital trade—and, from the looks of it in Washington, I’m just about the only one.

The Explosion in Digital Trade—Especially Gaming

Let’s talk about digital trade.

When Joe Biden and Donald Trump face off in tomorrow’s inaugural Mandelbaum Memorial Presidential Debate, the issue of international trade will almost certainly come up. Assuming it does, you can bet good money that the candidates and/or debate moderators will mention China and tariffs and the trade deficit and maybe Nippon Steel or electric vehicles or supply chain resiliency. An even safer bet, however, is that they’ll all ignore an area of trade that not only is important (for the economy and security) and booming (thanks to minimal government interference), but also one that the United States totally dominates. An area of trade that likely affects our daily lives more than all those container ships and steel imports and other things lamented daily by our current crop of politicians and pundits. (In fact, there’s a decent chance you’re using it right now.)

I’m talking about digital trade—and, from the looks of it in Washington, I’m just about the only one.

The Explosion in Digital Trade—Especially Gaming

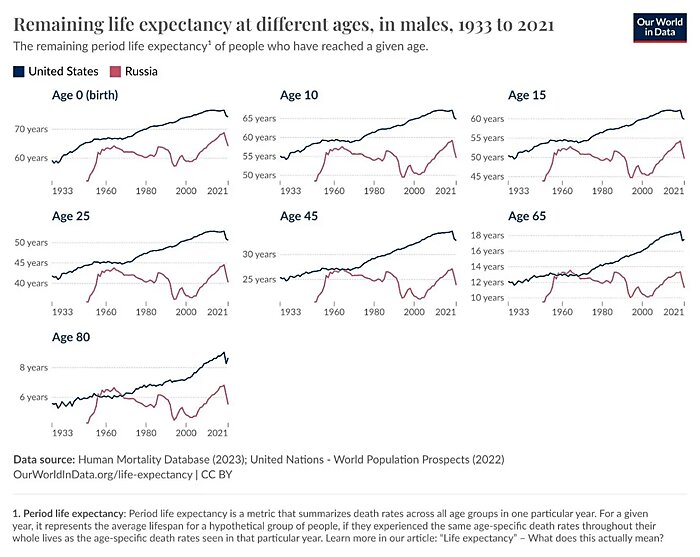

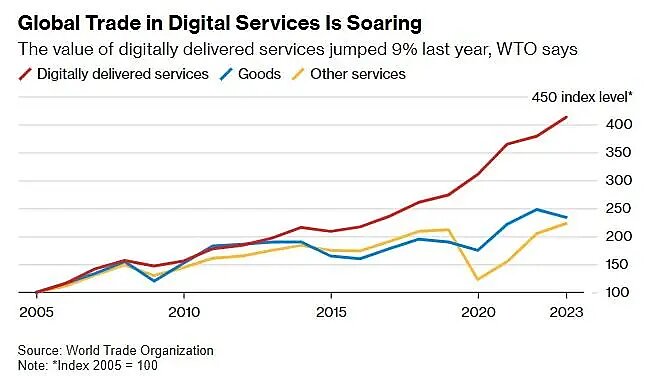

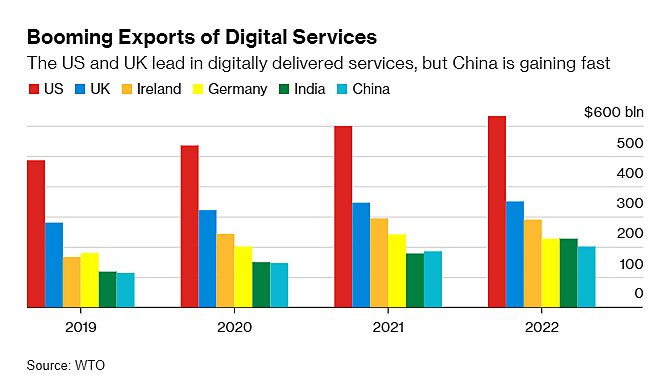

As I briefly discussed two years ago when everyone was predicting the “Death of Globalization” (LOL in retrospect), global trade in goods has slowed but trade in services—especially digital services—has exploded. Between 2005 and 2023, in fact, the value of digitally delivered services has more than quadrupled (and that’s surely a major understatement because digital trade is so difficult to measure):

As Middlebury College’s Gary Winslett explained last year in an essay for Cato’s globalization project, this rapid growth is owed to three big things: First, governments have lightly regulated digital trade and, in fact, have maintained a global moratorium on e‑commerce duties (tariffs) since 1995, thanks to a longstanding World Trade Organization agreement. Lessons abound.

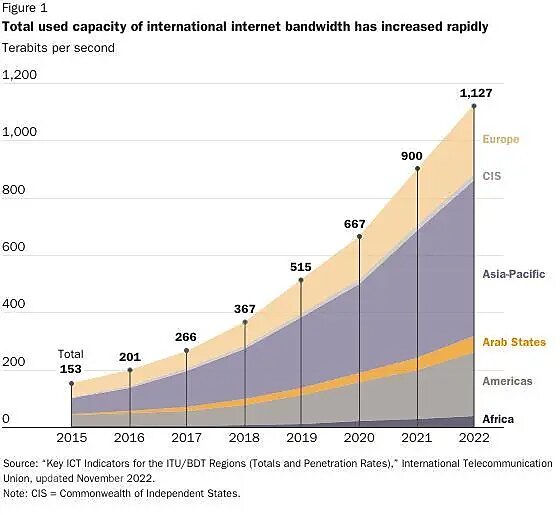

Second, incredible technological improvements—faster internet, better laptops and smartphones, etc.—have made it increasingly easy to send vast amounts of digital content around the world in milliseconds. Consider, for example, the exponential growth in international internet bandwidth—the infrastructure needed to carry our Zoom calls, shared docs, streaming media, and other digitally delivered services.

Third and most recently have been pandemic-related changes, many of which have since morphed into a new normal (see, e.g., remote work). Put all three together, and you get substantial increases in worldwide trade of not only stuff we typically think of as “digital services” (e.g., software and e‑commerce), but also many things that we don’t—at least not until very recently: lawyers in New York, Zoom tutors in Pakistan, fitness instructors in London, and countless others. Here’s Winslett explaining:

Digitalization has reduced what political economists call the “proximity burden.” With goods, the seller and the buyer do not normally need to be near each other. A pair of shoes can be made in Vietnam and purchased in Spain. Traditionally, that has not been the case with services. To provide a service, the seller and the buyer needed to be in the same room. Some services still work that way. If you want a haircut, you must physically go to a barber or stylist, and traveling too far to get that service easily overwhelms the value of the service, which means that the service has to be provided locally. Granted, many services continue to operate this way, but as the Zoom tutor and Peloton examples suggest, an increasing number of services do not, thanks to digitalization.

A variety of services—including content creation, engineering, legal assistance, and customer service—can now be traded internationally. This will continue to grow over time as technology progresses. Advances in augmented and virtual reality could make delivering services internationally even easier and more effective. Imagine being able to take an immersive, virtual cooking class from someone in Thailand or violin lessons from a musician in Poland, who could use augmented or virtual reality to help you better understand how to position your arms.

As AI and robotics proliferate, demographic challenges motivate, and immigration restrictions stubbornly persist, more physical tasks might similarly be digitized and traded across borders—what economist Richard Baldwin has deemed “globotics.”

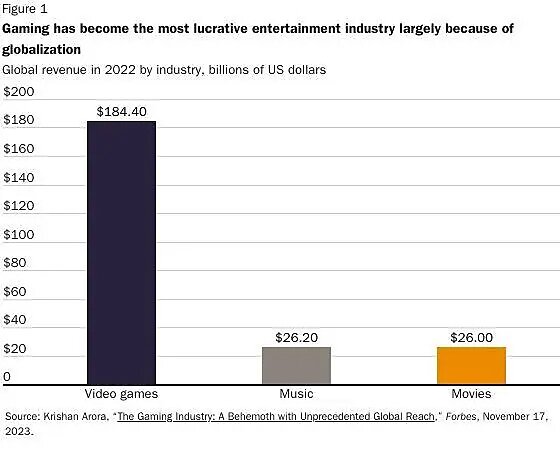

Right now, however, one of the boomiest areas of digital trade is—as Juan Londoño explains in a separate Cato essay—is online gaming (“esports”), which is big, big business these days. Before you boomers laugh at that last thought, please note that global revenue directly generated by video games is now three times larger than revenue generated by music and movies combined.

As Londoño details, the internet and globalization have driven this spectacular growth. Today, gamers can not only play games with and against other gamers from all over the world, but also watch others do the same—itself a huge, global business. Professional esports players and online streamers can make millions in winnings and endorsements, while many others have turned online gaming—playing/streaming, coaching, commenting, selling “virtual goods,” etc.—into a lucrative side hustle. The 2023 “League of Legends” world championship had a peak viewership of 6.4 million people, sold out a 16,000-seat venue in minutes, and generated $143 million in direct and indirect sponsorship revenue. That’s not (yet) Super Bowl numbers, but it’s still incredibly impressive: The just-completed 2024 NHL Stanley Cup finals, for example, averaged just 4.2 million viewers (and that was with a thrilling Game 7), while the amazing 2023 World Series—won by the amazing Texas Rangers (woot!)—averaged 9.1 million.

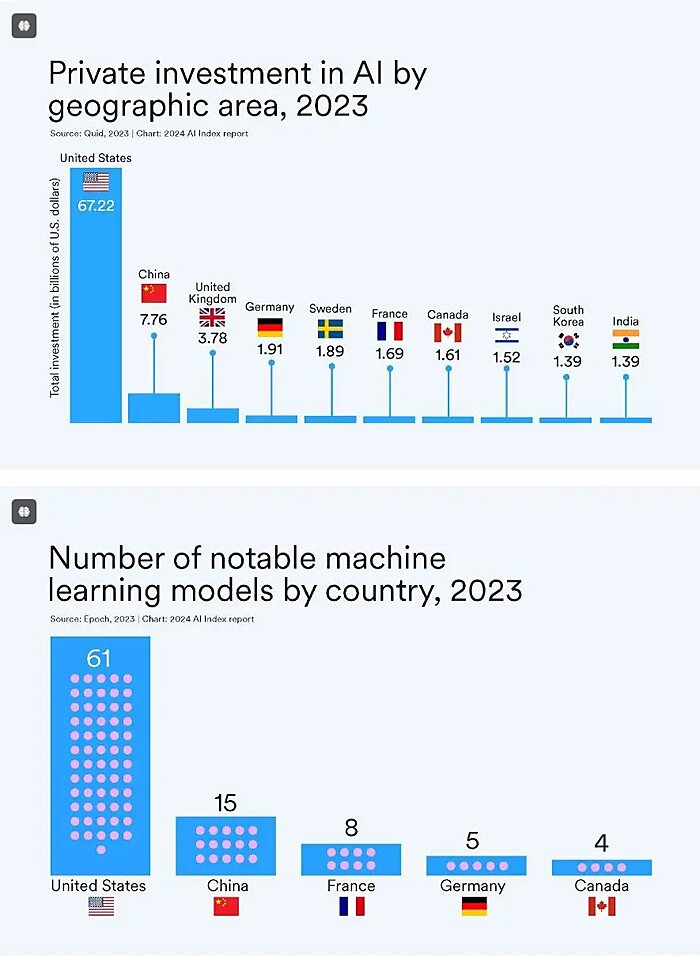

The globalization of gaming has generated immense benefits for not only American consumers (aka gamers), but also the American software, hardware, marketing, and related companies that facilitate it. Per Londoño, “the US gaming industry brought in approximately $68.3 billion in revenue in 2023… directly employs 104,080 people and sustains a workforce of 350,015 people when accounting for indirect jobs and other economic impacts.” (For reference, the U.S. iron and steel industry dominates U.S. trade policy today yet directly employed only 83,600 Americans last year.)

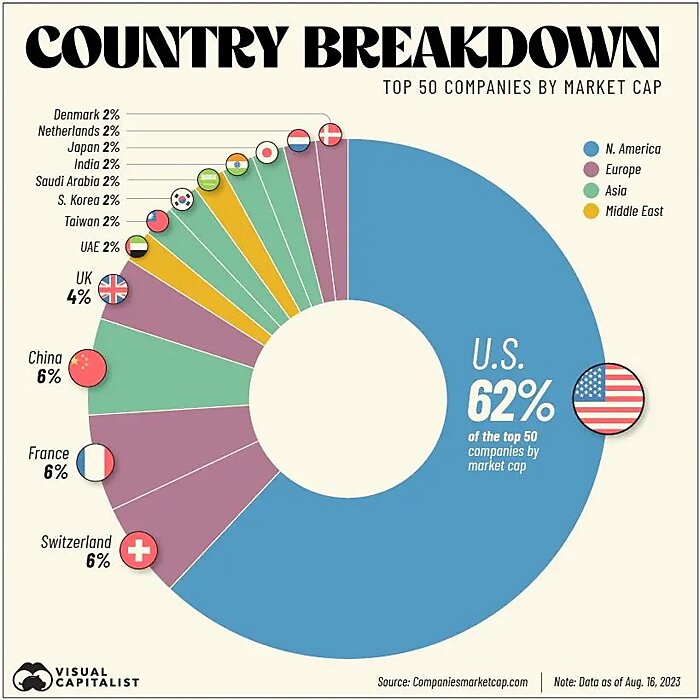

Overall, the United States is—by far—the world’s leading digital services provider:

Given the relatively low government barriers to online commerce and the United States’ impressive position, this is a modern free-trade success story—and a very big and promising one, at that. Yet, though trade and globalization are now constant political topics, we never hear a peep about any of this stuff. It’s all container ships and steel and soybeans and blah blah blah.

Gee, I wonder why?

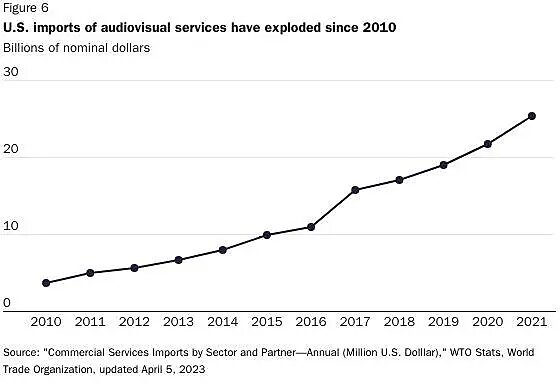

Trade Really Is Technology

There are surely many reasons for this glaring omission, beyond simply the age of our political candidates and the sclerosis that infects much of our policy. Among those reasons is that digital trade challenges the conventional wisdom about globalization in several important ways that today’s politicians might not appreciate. Americans, so we’re told, have embraced protectionism, yet—as Kevin Williamson noted last week—we all joyfully and regularly consume loads of digital “content” from all over the world and do so with little concern for its origins or means of delivery. Kevin is also surely correct that Americans would “riot” (figuratively, I think) if the U.S. government suddenly started interfering in our content consumption habits to protect, say, some random pundits or gamers or Victorian cosplayers in Milwaukee. We really like this stuff, as the eight-fold increase in “audiovisual services imports” (aka stuff like Squid Game and The Great British Bake Off) between 2010 and 2021 demonstrates. It’s undoubtedly increased even more since then.

Perhaps more importantly, digital trade uniquely demonstrates that, as economists have tried (and mostly failed) to explain, trade is just another form of technology, like cars or robots or computers. Professor Steven E. Landsburg famously explained this concept in the “Iowa Car Crop”:

There are two technologies for producing automobiles in America. One is to manufacture them in Detroit, and the other is to grow them in Iowa. Everybody knows about the first technology; let me tell you about the second. First you plant seeds, which are the raw material from which automobiles are constructed. You wait a few months until wheat appears. Then you harvest the wheat, load it onto ships, and sail the ships eastward into the Pacific Ocean. After a few months, the ships reappear with Toyotas on them.

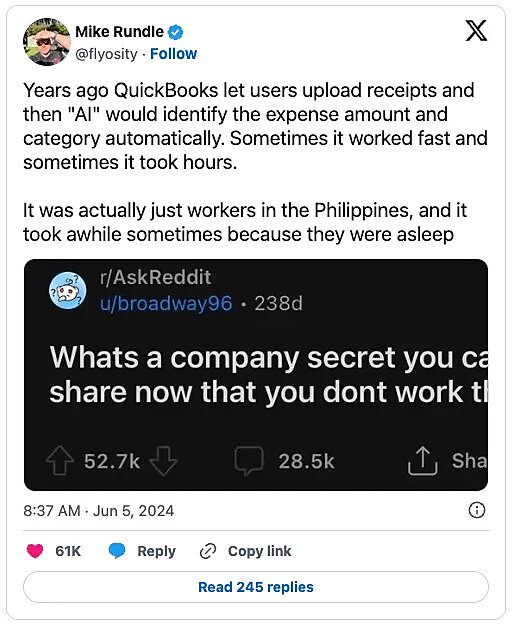

To other wonks and economists, this example is brilliant, but normies probably aren’t buying it. Digital trade and AI, however, have made the lesson much clearer and more tangible. For example, fast-food ordering kiosks have recently proliferated due to the high cost of labor in many U.S. cities. In California, the voice inside the kiosk is a “bot” (artificial intelligence) in the machine itself. In New York, on the other hand, the voice is an actual person living in the Philippines.

Here’s another, perhaps apocryphal but certainly funny, example of this blurring of economic lines that recently went viral:

We can surely argue about which approach, AI or “digital outsourcing,” is better for business or which is more humanitarian, but their local economic effects—on American workers, employers, competitors, consumers, the economy, and so on—are essentially identical. And, to the extent these changes are market-driven, the effects are mostly good: Businesses get needed support and can potentially expand other operations; consumers get needed services, often at lower prices or with more variety; competitors are pushed to keep up; and resources (labor, raw materials, capital, etc.) once dedicated to outsourced operations can be deployed elsewhere in more productive and viable U.S. businesses. Overall, the “winners” far outnumber “losers,” living standards rise, and the national economy is better off on net—a result repeatedly found in the economics literature on trade, including on the much-derided “China Shock.”

It’s thus unsurprising that studies find it difficult to distinguish the effects of trade from those of technology, including when it comes to jobs. After documenting the post-China Shock evolution of American manufacturers in a 2018 paper, for example, economists Teresa Fort, Justin Pierce, and Peter Schott acknowledge that the “data provide support for both trade- and technology-based explanations of the overall decline of [manufacturing] employment over this period, while also highlighting the difficulties of estimating an overall contribution for each mechanism.” Other papers have—contra the protectionist narrative—found that technology is actually more disruptive and “costly” for local workers than is trade. For example, a 2019 International Monetary Fund cross-country analysis of trade and technology shocks found that while both can raise regional unemployment and lower labor force participation, only automation has long-lasting harms. Regions hit by trade shocks, by contrast, actually ended up better off a couple years later.

Economists also understand, of course, that these shocks do have some downsides. Competition is difficult for incumbents whether it comes from a person across the street or in another state or from an alternative product or new technology. That pressure can, in turn, generate layoffs or bankruptcies, none of which are easy. But in these cases, too, economists know that the disruptions’ benefits far outweigh their costs, and that the risk of facing new competition—of being disrupted—is the “price” we all must pay to live in a dynamic, modern, and prosperous economy. Just as we wouldn’t want to live in a world of horse-drawn carriages, abacuses, and phlebotomy, we wouldn’t want to live in a world without trade—over short or long distances.

And our modern digital habits make this clear.

Summing It All Up

Thanks to new technologies and modest government meddling, digital trade has exploded in recent years, to Americans’ great benefit. Given the rapid acceleration of AI and robotics, as well as new and wildly popular forms of entertainment, we should expect more growth—and more benefits—in the years ahead, unless governments kill the “golden goose” with new taxes, regulations, and other types of interference. That risk, unfortunately, is today very real. Countries around the world have started proposing “digital services taxes,” demanding that certain data be “localized,” and pushing a “precautionary principle” approach to AI and other new digital technologies. The WTO’s important moratorium on e‑commerce duties was just extended, but only for two years—and further extensions are in doubt. Perhaps worst of all, the United States government has aligned with various left-wing critics and stopped leading on digital trade at the WTO and in other international forums, despite its many economic benefits and U.S. companies’ global dominance.

That’s a heckuva lot more important than steel (or whatever). Maybe someone should talk about it?

Note: Capitolism will be off next week.

Chart(s) of the Week