When news broke last week that Donald Trump had offhandedly proposed to replace the income tax with tariffs, my immediate reaction was similar to The Dispatch’s own Kevin Williamson, albeit with less rhetorical flair. Yet, Trump’s idea received enough credulous reporting and curious—even supportive—online commentary that it warrants elaborating on why Kevin’s instincts are indeed correct. So, even though no one could possibly prefer I write about things other than tariffs more than me, we’ll dig into Trump’s latest idea today.

Fortunately, we at Cato expected that tariffs would be a prominent political talking point this year and just published an accessible primer on everything tariffs—who pays them, their economic effects, and so on—by the Tax Foundation’s Erica York. Capitolism has already covered much of the essay’s substance at (considerable) length, but we’ve never really addressed whether tariffs are a good way for governments to raise revenue.

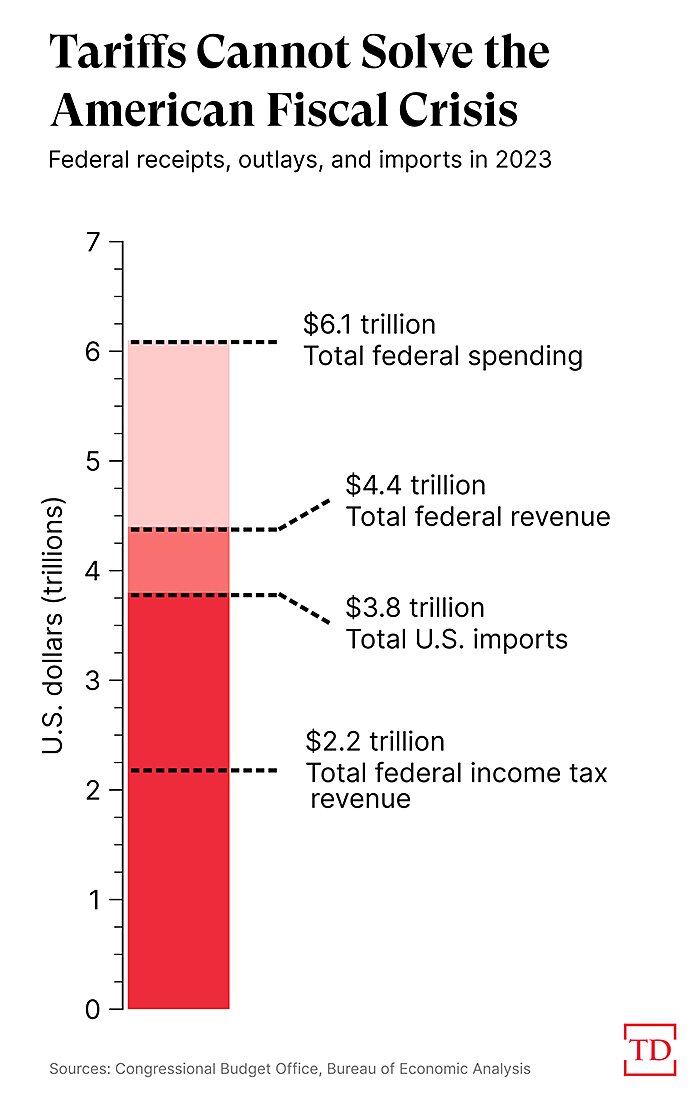

Spoiler: no. Even setting aside the many economic problems that tariffs create, trying to use them to fund the U.S. government is not only mathematically implausible even with radical spending cuts, it also raises all sorts of practical problems and economic uncertainties that render the plan even more problematic than Kevin (humorously) leads on.

The Basic Math Problem

The first big problem is basic math. The United States imported around $3.8 trillion total last year ($3.1 trillion in goods; $714 billion in services), but the federal government spent $6.1 trillion while raising just $4.4 trillion (libertarian sigh). So, in a situation where nothing changed in response to higher tariffs (more on that in a second), the federal government would need to impose a tariff on all imports of goods and services of around 160 percent to cover current spending and 116 percent to replace just revenues. The math’s a little less challenging if you just want to replace income taxes with tariffs: Total income tax revenue in 2023 was almost $2.2 trillion, so we’d need a mere (sarcasm) 58 percent global tariff to cover that amount.

Various nips and tucks to the topline data don’t change the conclusion. Apply tariffs to just goods and you shrink the tax base, meaning you’d need even higher tariff rates to cover whatever revenues you’re trying to replace. Nix only income taxes for the bottom 50 percent of American taxpayers, and you can apply much lower tariff rates (maybe just a few percentage points). However, that’s only because those folks pay almost no income tax (accounting for just 2.3 percent of all income taxes paid in 2021). In that case, you’d be adding a lower global tariff but providing almost no actual tax relief and keeping the current, messy income tax system for tens of millions of workers. Since the tariffs would be paid by all Americans while income taxes are today mainly paid by high earners, the new tariff regime would—as this recent Peterson Institute analysis shows—probably increase taxes on the poor even if it canceled out their income taxes entirely. (York further explains that U.S. tariffs today are doubly regressive. They “create a larger burden on poorer households because poorer households generally spend more money on traded goods as a share of their income than wealthier households,” and the design of existing tariffs exacerbates the regressivity because they “are systematically higher for lower‐end versions of goods than higher‐end versions.”)

But wait, it gets worse.

The bad math above is actually much better than what would happen in the real world because Americans would change their behavior in response to high tariffs. They’d import less because imports cost more. That result might be good for certain U.S. manufacturers who have new (captive) customers and can charge higher prices, but it’s a big problem for those wanting to use tariffs as major revenue-raisers because the taxes are only paid on imports that enter the country. Fewer imports would mean a smaller tax base, which in turn would mean you’d need even higher tariffs to raise the same amount of revenue. But if you raise tariffs too high, you get no imports at all—and thus no revenue. Oops!

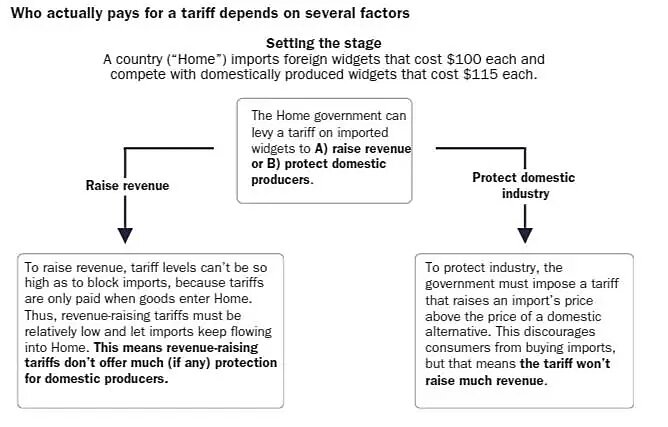

This tension is one of the many contradictions in the promises of today’s tariff advocates: Protectionist tariffs discourage imports but don’t raise much revenue, while revenue-raising tariffs don’t do much protecting because they have to be low enough to allow lots of imports. The snazzy flowchart in York’s essay lays this out nicely:

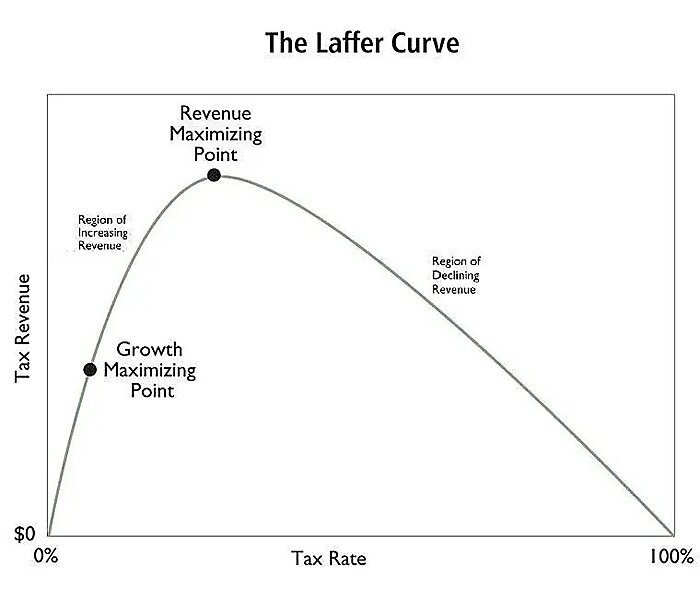

This iron law of economics is one that, as Dartmouth economic historian Doug Irwin explains, even protectionist heroes like Alexander Hamilton understood. Congress adopted tariffs that the founding father (and author of the famous/infamous Report on Manufactures) recommended, but these tariffs “were not highly protectionist because Hamilton feared discouraging imports, which were the critical tax base on which he planned to fund the public debt.” This dynamic is also something that today’s Republicans understand—at least when it comes to income taxes: the oft-cited “Laffer curve” posits that a tax on a certain economic activity (usually labor) won’t raise any revenue when it’s set at zero or 100 percent, with a hump (curve) in between:

As you can see, tax revenue generally rises with the rate until its costs get so onerous that the taxed activity declines and revenue begins to fall. Economists disagree about the exact “revenue-maximizing” tax rate and about the taxes’ growth effects, but they all agree that the Laffer Curve exists—including for tariffs.

In practice, this means that there’s a hard limit to how high tariffs can go and how much revenue they can effectively raise, a limit that depends on the extent to which consumers shift away from imports as tariffs increase their price (aka the “elasticity”). That shift, in turn, depends on the product at issue: If consumers have no choice but to keep buying a certain imported good or service, you can raise tariffs pretty high. If they have lots of alternatives, on the other hand, tariffs have to stay low. Setting aside whether maximizing tariff revenue is a good idea economically, implementing one would depend on finding the sweet spot for each good or service—a rate high enough to raise lots of money but low enough to keep imports flowing.

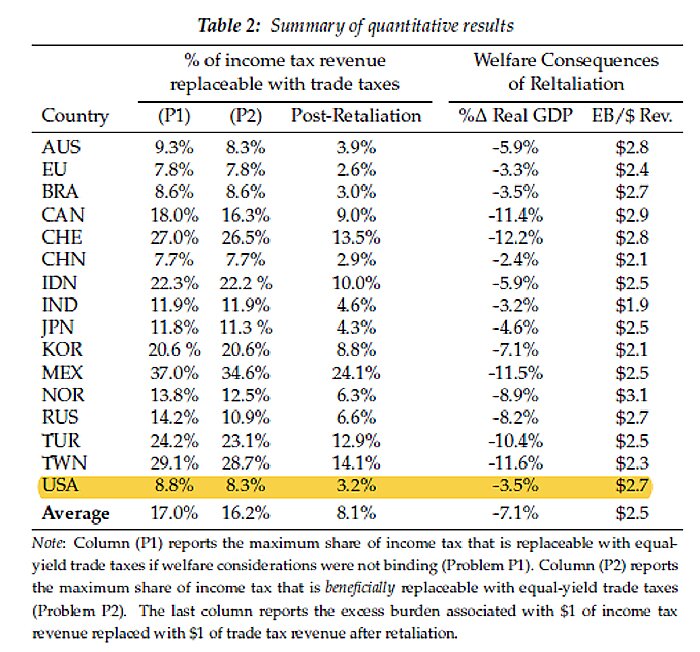

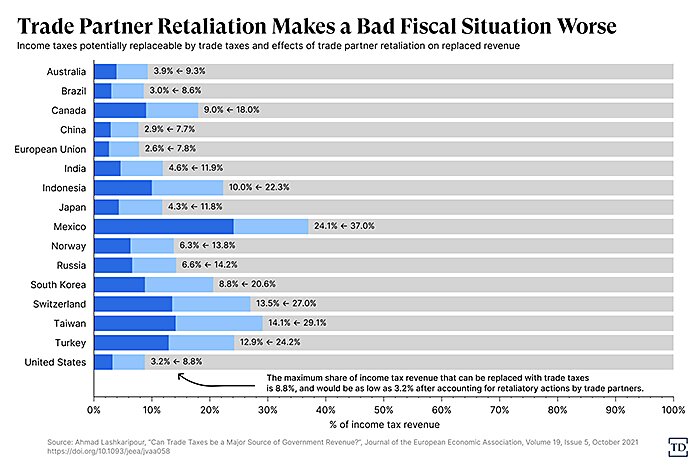

Common sense suggests that this tariff-maximizing rate would be much lower than one needed to replace most or all of the U.S. income tax, an intuitive conclusion confirmed via rigorous economic analysis. In a 2020 paper, Indiana University economist Ahmad Lashkaripour calculated industry-specific elasticities (based on data from 43 major economies and 56 traded and service-related industries) to model how just much government (non-trade) revenue could be replaced by a system of revenue-maximizing tariffs on imports and exports. As shown in the table below, Lashkaripour finds that trade taxes could replace at most 8.8 percent of current income tax revenues:

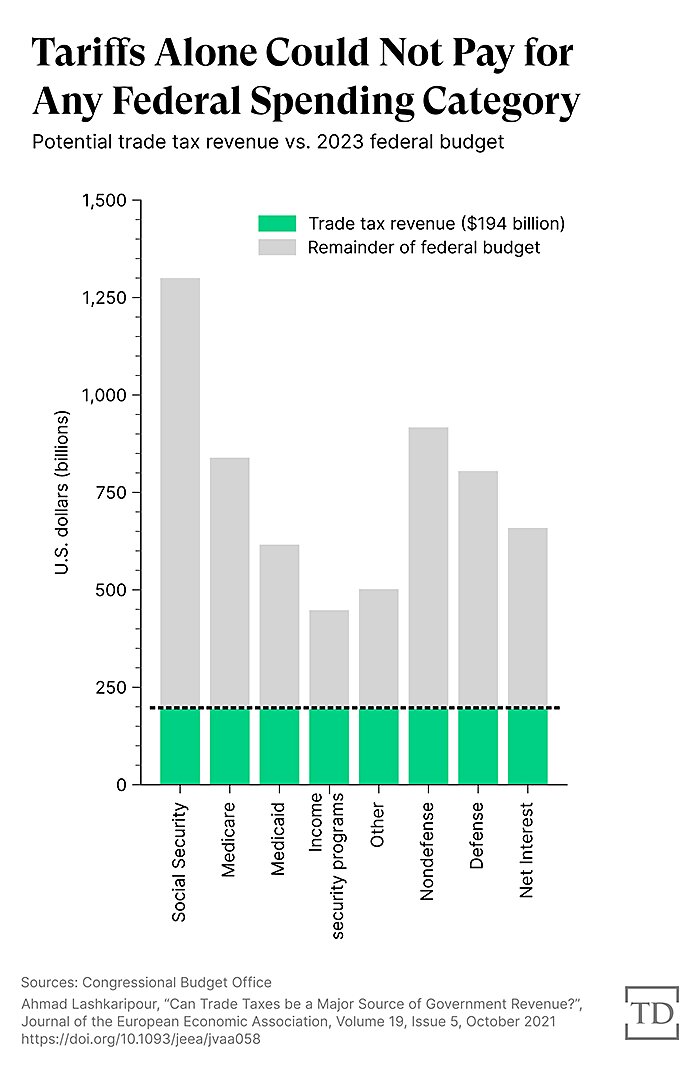

If applied to 2023, that’d mean a system of U.S. trade taxes could replace just $194 billion of the $2.2 trillion in income taxes raised that year. That’s not even one-fourth of U.S. defense spending or one-third of the federal government’s interest payments last year ($805 billion and 659 billion, respectively).

Lashkaripour’s calculations are just one estimate, of course, but they’re overly generous in at least one way: They include export taxes that Trump isn’t proposing and that are unconstitutional. Regardless, even if you double or triple his figures, you’re still not getting anywhere in terms of paying for even a sliver of current U.S. government operations.

That point is worth reiterating, as some have argued for Trump’s idea because it would necessarily mean less spending—something I, being a libertarian and all, also strongly support. But c’mon, folks, let’s get real. Forget for a second the small fact that Trump was a big spender when in office and isn’t promising any serious spending cuts—especially not to entitlements, which drive our long-term spending problem. There is no remotely plausible situation in which the numbers here work.

By contrast, consider my Cato colleague Adam Michel’s brand new and intellectually serious plan to radically improve the tax code. He recommends steep tax cuts that would reduce tax revenues if implemented. The tax cuts could/should be best paired with spending cuts, but he also offers offsetting changes to the income tax that would raise trillions of dollars (closing loopholes, repealing tax credits, etc.) and make the plan roughly revenue-neutral in the off chance (sarcasm, again) that Congress is not ready to make dramatic spending reforms. All scenarios generate trillions of dollars more revenue than tariffs ever could.

So, yes, we need to enact bold tax and spending reforms. But relying on tariffs? It’s unicorn math all the way down.

The Practical Problems

The tariff plan would also be plagued with practical problems. In just coverage alone, would Trump’s tariffs apply to all imported necessities like food and beverages (almost $200 billion last year); clothing ($51 billion); shoes ($18 billion); and medicines ($203 billion)? Would it apply to the almost half of all imported goods that are industrial inputs used by American manufacturers to produce (and often export) other stuff? Would it apply to that $700-plus billion in services, including the ever-increasing share transmitted digitally or the $149 billion that Americans spent traveling abroad last year (considered a “travel services import”)? Would it apply to Americans’ personal, small-dollar purchases of retail items, whether made as tourists abroad or via direct mail?

The list goes on and on.

Indeed, as York reminded us Monday, these kinds of sensitivities pushed Trump in 2019 to balk at applying tariffs on many consumer-facing goods from China (he supposedly didn’t want them to spoil Americans’ Christmas season—LOL). Now we’re to expect tariffs on everything from everywhere, including stuff like tropical fruit or trips to Paris that you just can’t get here, American consumers be damned? Seems unlikely.

And this brings us to the next practical problem: administrability and evasion. Exceptions and exemptions mean not only a narrower, opaque tax base and less tariff revenue but also more difficulty determining what to tax and collecting any taxes that ultimately apply. Tariff rates would also need to vary by product to maximize revenue (see “elasticities” discussion above). For goods alone, however, there are more than 17,000 unique items listed in the current U.S. tariff code, and even with that level of detail there are constant legal disputes about what line applies to some random product.

New and variable tariffs would increase these disputes and efforts to game the new system. Small-dollar personal purchases from abroad, for example, are now controversial in part because these “de minimis” imports exploded after Trump’s last rounds of tariffs. More tariffs would lead to more searches for loopholes and even more creative “tariff engineering,” not to mention good ol’ smuggling. (In a new blog post, York estimates that as much as 15 percent of tariff revenue would be lost to this kind of “noncompliance.”) Global supply chains would similarly adapt. Markets never stand still.

Services could be even messier, especially when embedded in manufactured goods or delivered digitally. For example, a U.S.-based person or company (e.g., Netflix) could import a single digital item (e.g., Squid Game), and then resell copies of it in the U.S. for billions of dollars. Software and other digital goods, meanwhile, can also be classified as a “service.” The opportunity for evasion is endless, and enforcement would require an army of tax collectors stationed at U.S. borders and in Washington to monitor our every email, zoom call, and invoice. (Bring on the new U.S. Pirate Force!)

As I wrote years ago, “We live in a strikingly different world today than the one inhabited by supposed protectionist champions such as Alexander Hamilton and Abraham Lincoln.” Theirs was a world with less global trade (especially in services), few transnational supply chains, national economies reliant on agriculture and a few basic manufacturers, and people who would’ve (rightly!) considered digital trade to be witchcraft. For these and other reasons, looking to the 1800s for trade policy inspiration isn’t just economically wrongheaded; it’s foolish.

Yet here we are.

The ‘And Then What Happens?’ Problem

Finally, there’s what happens after these tariffs are imposed, both here and abroad. On the latter, many countries would surely respond to new U.S. tariffs with tariffs of their own on American goods and services. That retaliation would hurt U.S. exporters (farmers, sure, but also in tech and other important, world-beating services) and the economy, just as retaliation to Trump’s previous tariffs did years ago. However, as Lashkaripour shows in his paper, it’d also hurt government revenues.

In particular, he finds that a revenue-maximizing tariff regime and the full-fledged trade war that follows would generate significant distortions (as compared to a low-tariff regime with an income tax) that reduce U.S. real GDP, shrink the U.S. tax base, and in turn force the federal government to impose other domestic taxes to make up for the revenue shortfall. Thus, per his calculations, tariffs in a trade war scenario not only make us all poorer but also would end up raising just 3.3 percent (dark blue bar) of the revenue that our current income tax generates:

One can certainly question whether all governments would retaliate and whether the U.S. government would raise other taxes if/when they did. Nevertheless, given how Trump’s other tariffs played out in 2018–19—China, the European Union, India and others did retaliate, and U.S. GDP did shrink (see, again, York’s essay for the receipts)—we should expect Lashkaripour’s conclusions to be at least directionally correct. In other words, we’d see even less tariff revenue than the pittance a non-retaliation scenario would generate.

The tariff regime would surely raise other big questions, such as how the U.S. dollar and the Federal Reserve would respond. As York explains, both theory and practice show that tariff increases are often accompanied by increases in the value of a country’s local currency, which in turn reduces exports regardless of retaliation. (Trump’s advisers, meanwhile, say they want a weaker dollar. Oops!) On the other hand, a tariff on a product typically means a higher price overall in the importing market, not just for imports—another common mistake about tariffs. (This is not only backed up by research but also just common sense: Non-tariffed alternatives are usually more expensive than the tariffed ones; if they weren’t, we’d already be buying them without any tariffs.) So, a big global tariff would likely generate a significant, one-time increase in the general price level in the United States. How would the Fed respond to that?

Summing It All Up

Tax wonks on the right stick to a few basic principles when dreaming up grand plans to fix our broken U.S. tax code and boost American living standards. As Michel lays out, a tax system should feature relatively low rates and simple, transparent rules; a broad tax base with few (if any) loopholes and economic distortions (e.g., by treating income from labor and capital equally); and permanence. It should prioritize growth and fairness, while not adding to the deficit. The Tax Foundation offers similar principles on its list: simplicity (easy for taxpayers to comply and governments to administer and enforce), transparency (clearly and plainly define what taxpayers must pay and when), neutrality (neither encouraging nor discouraging personal or business decisions), and stability (maintaining consistency and predictability). Both cite broad-based consumption taxes, such as a retail sales tax or value-added tax (VAT), as prominent examples of systems that adhere to the aforementioned principles. (“Consumed‐income taxes,” which are income taxes with a deduction for savings, are another.)

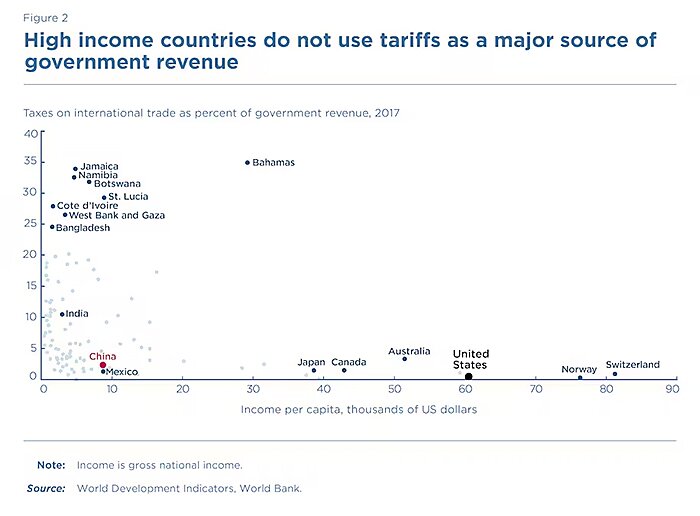

Tariffs, on the other hand, achieve none of these objectives. Rates would be high, complicated, and opaque; the tax base would be small (imports are around 15 percent of GDP and 11 percent of U.S. consumption) and almost certainly rife with exceptions and loopholes; distortions would be significant; gaming and evasion would be rampant; enforcement would be onerous, unpredictable, and difficult (at best). We’d get lower economic growth and worsened foreign relations, and, to top it all off, we wouldn’t even raise much revenue. Tariffs are a 19th-century tool for a 21st-century economy, and there’s a reason only poor countries rely on them to fund government operations: They have no other choice.

As Michel notes in a new blog post, the run-up to the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act’s expiration next year has seen many serious plans from the left, right, and center for reforming U.S. tax policy in a sane and fiscally responsible manner. There are sure to be more in the months ahead—but tariffs ain’t one of ‘em.

Charts of the Week