Readers of Capitolism surely know by now that I’m a fan of immigration and believe the United States’ illegal immigration problem starts with its legal immigration problem (i.e., that our broken system makes it too darn difficult to move, work, and stay here). Nevertheless, it’s also objectively correct that illegal immigration is, well, illegal, and not even a bleeding-heart squish like me would vigorously object to the federal government deporting violent criminals who snuck into the country.

It’s a more open question, however, as to whether the widescale deportations promised (and seemingly begun) by the new Trump administration are worth the massive amount of government and private resources—years of work, billions of dollars, thousands of people, etc. —needed to deport even a fraction of the 11 million illegal immigrants, most of whom are not violent criminals, that the Trump administration has promised to remove. (And that’s even leaving aside the moral, civil liberties, and efficacy concerns that the government’s efforts raise.)

Many who vigorously shout “YES IT IS” to that question often point to not just “the law” but the economic benefits that deportations would supposedly bring to the U.S. economy, particularly for U.S. workers (native-born and legal immigrants) that would—again, supposedly—get better jobs and higher wages if they didn’t have to compete with undocumented workers in the U.S. labor market. Yet decades of research on several different periods of U.S. history—both distant and recent—show that the overall labor market effects of the Trump administration’s deportation promises should be counted as another cost, not benefit, to any such actions—for not just illegal immigrants and their families but most American workers, too.

The Long History of U.S. Deportations

Indeed, the history of large-scale U.S. government immigration actions gives us plenty to worry about when it comes to the economic effects of the new Trump deportations. Let’s start in the 19th century, when concerns about immigrants stealing Americans’ jobs in Western states resulted in the first big crackdown on immigration in U.S. history—the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which banned Chinese laborers from immigrating to the United States and pushed out many Chinese laborers already here. According to a recent paper examining the Act’s effects on eight Western states, the law unsurprisingly reduced the Chinese labor supply—both skilled and unskilled workers—by 64 percent in the region. More surprisingly, however, was that the act:

- Reduced the white male labor supply by 28 percent and reduced these workers’ lifetime earnings, too.

- Reduced total manufacturing output in the region by 62 percent, the number of manufacturing establishments in the region 54 to 69 percent, and manufacturing labor productivity by an imprecise amount. (The damage was so substantial because Western factories back then “were small and mostly relied on labor-intensive production.”)

- Generally acted as a drag on economic growth in the Western U.S. (which was otherwise growing rapidly during the late 19th and early 20th centuries).

The authors thus conclude that “the Chinese Exclusion Act led to negative economic effects for most non-Chinese workers and likely slowed the economic development of the western United States for many decades.” Their main lesson: “productive immigrant labor may be hard to replace.”

Indeed.

Of course, the Chinese Exclusion Act’s damage back then was likely greater than it’d be today because we’ve (thankfully!) improved on 19th-century mobility, technology, amenities (AC, especially), and social integration—things that would’ve amplified the act’s economic shock by limiting labor adjustment and something the study’s authors readily acknowledge.

Fortunately, there’s plenty of research on subsequent periods of U.S. history that show similar (though smaller) effects—during economic downturns as well as booms—for similar reasons.

Between 1929 and 1934, the United States government deported—some by force and others by persuasion—at least 400,000 Mexicans (many of whom were U.S.-born!) to boost native-born employment during the Great Depression. As a result of this policy, the Mexican population in the United States declined dramatically in the 1930s, but, as economists Jongkwan Lee and colleagues have found, American workers didn’t benefit. Instead, “Mexican repatriations resulted in reduced employment and occupational downgrading for U.S. natives,” particularly for low-skilled workers and workers in urban areas. They cite three likely reasons for the disappointing results: 1) companies in immigrant-dependent industries like agriculture and construction suffered, reducing their demand for native workers; 2) Mexicans’ departures reduced urban populations and, in turn, demand for local goods and services, as well as overall economic growth in these areas; and 3) firms that survived the policy’s initial economic shocks restructured to utilize more labor-saving technologies instead of hiring native-born workers.

In the mid-1960s, the United States ceased its successful Bracero Program that provided Mexican nationals with expanded access to guest worker visas (thus dramatically reducing illegal immigration, by the way). The goal of the program’s cancellation—which “caused the exclusion of roughly half a million seasonally-employed Mexican farm workers from the labor force”—was to increase the wages and employment of American farm workers. Yet, in reviewing novel state-level employment and migration data, economist Michael Clemens and his co-authors found no such effects in the most exposed states. Instead, wages in states with high or moderate levels of Mexican migrant workers (and thus higher levels of bracero effects) “rose more slowly after bracero exclusion than wages in states with no exposure to exclusion.” Employment levels, meanwhile, showed no significant effects across states. The authors conclude that “bracero exclusion failed as active labor market policy,” theorizing that—instead of raising wages and hiring more American workers—U.S. farmers turned to harvesting machines or, where rapid mechanization wasn’t possible (e.g., for delicate fruits), simply produced less.

Most recently, the United States during the Obama years ramped up immigration enforcement and deportations via the “Secure Communities” (SC) program, which sought to detect and remove illegal immigrants by increasing information-sharing between the federal government and local law enforcement agencies and was revived during the first Trump term. As economist Chloe East recently documented for the Brookings Institution, SC between 2008 and 2014 resulted in the deportation of about 400,000 people, mostly men, and had a broader “chilling effect” on illegal and legal migrants’ willingness to engage in the formal economy. As she documents, “even people not targeted for deportation became fearful of leaving their house to do routine things like go to work…” because the program—like what Trump’s promising today—didn’t just target serious, violent criminals but instead deported lots of migrants with minor, nonviolent convictions (or none at all).

Once again, however, the removal of several hundred thousand workers from the U.S. labor market was not a boon for the U.S. economy or most native-born workers. Instead, East and her colleagues found that, while SC “decreased the employment of likely undocumented immigrants” via deportations and the aforementioned chilling effects, the program also slightly decreased U.S.-born workers’ employment and hourly wages on average. They posit that these negative effects were driven by two factors: First, firms with increased labor costs decreased their overall output and job creation, meaning that the modest gains experienced by low-wage native workers were more than offset by losses among everyone else; second, fewer people meant less local consumption, which in turn meant less economic activity (and demand for labor) in the localities at issue.

Other studies of SC have expanded on these findings in specific industries. In a separate paper, East and others found that SC “reduced the labor supply of college-educated U.S.-born mothers with young children,” with many working moms unemployed or underemployed for years after their kids were born, because the policy made household services more expensive (by reducing the available workforce) and thus discouraged educated moms from working outside of the home. Relatedly, research shows that SC reduced the wages at formal childcare centers for immigrants and native workers (both low- and high-education), as well as the overall number of childcare facilities, due to a lack of workers and fewer people seeking childcare. SC has also been found to have disproportionately harmed the U.S. construction workforce (immigrant and U.S.-born, across all wage- and skill-levels), thus decreasing residential homebuilding and increasing home prices, with minimal offsetting downward price pressures due to reduced demand for housing. Finally, SC has been found to have harmed entrepreneurship, modestly deterring individuals from undertaking self-employment and significantly reducing the earnings of those who still took the plunge, especially for white, male, U.S.-born entrepreneurs. (And, to top it all off, SC might not have even reduced crime!)

Lessons Abound

In case after case and regardless of period, past U.S. efforts to remove illegal immigrants have proven economically costly—for immigrants, certain industries and localities, and even native-born workers and the economy overall. This raises the obvious question of why, and East provides much of the answer in her piece for Brookings:

The prevailing view used to be that foreign-born and U.S.-born workers are substitutes, meaning that when one foreign-born worker takes a job, there is one less job for a U.S.-born worker. But economists have now shown several reasons why the economy is not a zero-sum game: because unauthorized immigrants work in different occupations from the U.S.-born, because they create demand for goods and services, and because they contribute to the long-run fiscal health of the country.

We see the first two dynamics repeatedly in the research outlined above. In general, government reductions in illegal immigrants’ labor supply didn’t draw many American workers into the occupations in which the immigrants mainly worked—occupations that often supported other American workers—but did reduce overall local demand for goods and services. And the relatively few American workers who did fill some of these new vacancies ended up in jobs that were worse than what these workers otherwise would’ve done. As a result, deportations and related restrictions caused local economic activity to be depressed, while harming many U.S. businesses and workers along the way. (These dynamics also explain why various studies have found new immigrant labor supply, legal or illegal, to have little to no negative wage effects on native U.S. workers, including other immigrants, even though most illegal immigrants are likely coming here for work.)

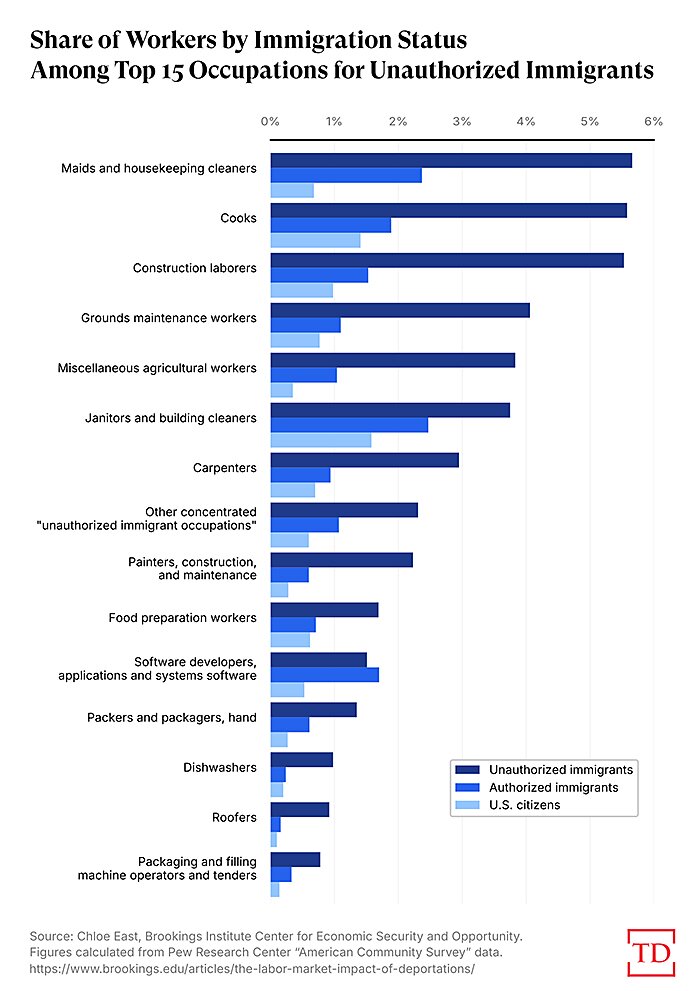

We should expect similar effects this time around—if not more so. For starters, East shows that today illegal immigrants generally work in “low-paying, dangerous and otherwise less attractive jobs” that U.S.-born workers and legal immigrants tend to shy away from:

As we’ve discussed, moreover, the U.S. labor market—now and likely in the future—remains tight (thanks to demographics and other factors), and there are simply not millions and millions of idle American workers sitting on the sidelines just itching to take these newly open jobs. To the extent Trump’s broad deportation promises come to fruition, we can expect many immigrant-dependent industries to suffer, few American workers to gain, many other Americans to lose, and plenty of headlines like this along the way:

The California Farm Bureau says fears in the Central Valley have led to migrant farmworkers not showing up for work, which has virtually halted the area’s citrus harvest.https://t.co/fDsSWZSfV1

— NBC Los Angeles (@NBCLA) January 27, 2025

Summing It All Up

Maybe you think these costs and others are worth the price, and that no amount of illegal immigrant labor is acceptable in today’s United States. Being a devoted cost-benefit guy obsessed with scarcity and opportunity cost and fearful of a big, intrusive state (and being a soft-hearted lib, to boot), I disagree. Regardless, we should all have our eyes wide open about the trade-offs that any big, broad deportation policy entails, beyond simply the ample resources required to (maybe) pull it off. In this particular case, the tradeoffs are real and significant, and they include costs borne by the very people that the policy is supposedly intended to help.

Chart(s) of the Week

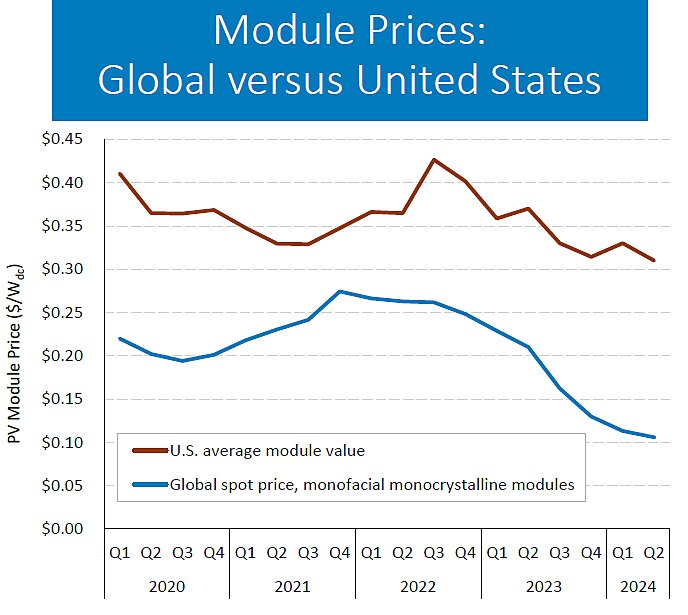

Massive (190 percent!) U.S. solar panel price premium, thanks in part to tariffs: