In an ALL CAPS tweet last week, President Trump reassured America’s farmers that their service in the trade war continues to entitle them to federal subsidies “UNTIL SUCH TIME AS THE TRADE DEALS WITH CHINA, MEXICO, CANADA AND OTHERS FULLY KICK IN…” According to Trump, that assistance—provided to help farmers cope with tanking export revenues thanks to foreign retaliation for Trump’s tariffs—will be “PAID FOR OUT OF THE MASSIVE TARIFF MONEY COMING INTO THE USA!”

Well, in one sense, Trump is right. U.S. tariff coffers are overflowing with record amounts of duties collected on imports. However, the money isn’t “coming into” the country. It’s already here. It’s just being transferred from U.S. businesses—mostly manufacturers—to the U.S. government. The implication that the “money coming into the USA” is some windfall courtesy of foreign producers and governments is utterly false. Trump is playing a shell game here, hoping the public will lose sight of the ball. He’s eager to conceal that he is stealing from the manufacturing sector to buy farm state votes.

For many decades, annual U.S. tariff “revenues” (to be clear, they’re revenues to the government, but costs to the private sector) as a percentage of annual U.S. import value was remarkably consistent. Between 2001 and 2016, for example, annual tariff collections amounted to between 1.2 percent and 1.7 percent of the value of total imports. In 2017, the last year unaffected by Trump’s trade policies (tariffs didn’t start until 2018), U.S. import value totaled $2.33 trillion and the $33 billion of duties collected on those imports amounted to a trade-weighted average tariff of 1.4 percent—precisely, the average over the previous 16 years.

In 2018, Trump’s tariffs began to take effect at different points in the year. The duties collected for the year surged from $33 billion to $48 billion, or to 1.9 percent of a still-growing pool of imports. Then, in 2019, it all hit the fan. Tariffs on steel and aluminum from nearly everywhere, and large swaths of products from China were in effect for the whole year. Year-end data show that total import value declined, but duties collected skyrocketed to a whopping $71 billion—a 123 percent increase over 2017.

The trade-weighted average tariff of 1.4 percent that had prevailed from 2001 to 2017 doubled to 2.8 percent in 2019. If the historical rate of 1.4 percent had applied to 2018 and 2019 imports, U.S. Customs would have collected duties of $71 billion over two years. Instead, over those two years, Customs collected $129 billion in tariffs for a “windfall” of $58 billion. Except it’s not a windfall. Those tariffs were paid to U.S. Customs by U.S. importers and those importers aren’t volunteering to dive on grenades to save the rest of us from this massive tax burden. The $58 billion is a tax that has been imposed on U.S. producers, logistics providers, wholesalers, retailers, and consumers.

A closer look at the import statistics provides a better picture of exactly whom is bearing the burden of Trump’s tariffs or—to be honest—who is financing Trump’s effort to placate farmers with lump sums that are nothing more than efforts to buy their votes.

Between 2017 (pre-tariff base year) and 2019 (tariffs fully implemented), duty collections increased from $33 billion to $71 billion. That $38 billion increase was generated from new taxes imposed on U.S. importers of a broad array of goods. Most (almost three-quarters) of that $38 billion increase was generated from taxes imposed on the material inputs and finished goods of eight manufacturing industries listed in the table below. (These “industries” correspond to what is known as the “Chapter” level or the “2‑digit” level of the Harmonized Tariff Schedule, which really captures multiple industries within the broad category descriptions in the table below.)

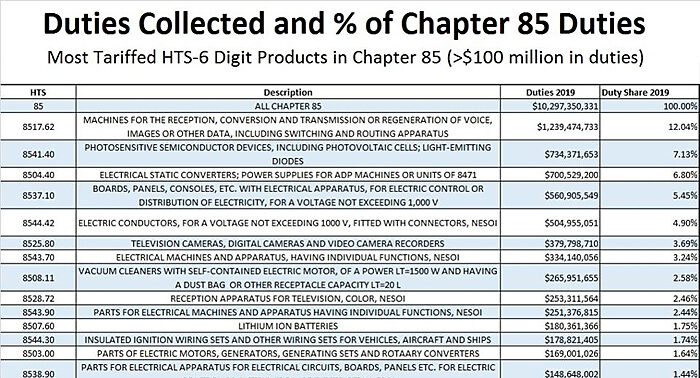

So, among the facts and trends the table reveals is that duties collected on imports of electrical machinery and equipment, etc. (HTS Chapter 85) exceeded $10.2 billion in 2019, which was an $8.3 billion increase over the duties collected on them in 2017. That increase accounts for 21.7 percent of the increase in all duties collected between 2017 and 2019, which renders producers of “electrical machinery and equipment parts thereof” the U.S. industry most burdened by the tariff increases. More than one in every five dollars of that $38 billion “windfall,” which Trump plans to wire to the bank accounts of farmers in Iowa, Illinois, and Nebraska, will come from the wallets of producers and consumers (and retailers, distributors, etc.) of electrical machinery, equipment, and their parts.

The following table provides a clearer idea of exactly which kinds of firms in the electrical machinery industries are flipping the bill for farmers. Importers of this list of 6‑digit HTS products, which include manufacturers who rely on these inputs to produce their machinery, are paying a sizable chunk of Trump’s tariffs (almost 22% of the increase in all tariffs, as noted in the table above). They include firms that use electrical plugs, sockets, processors, printed circuits, motors, semiconductors, and other parts. They paid $8.3 billion more tariffs in 2019 than they did in 2017.

The second most burdened set of industries import components and final goods that fall under Chapter 84. As noted in the first table, importers of these products paid $6.6 billion more in tariffs in 2019 than they did in 2017. The most tariffed products in Chapter 84 are listed in the table below.

The bottom line is that Trump’s tariffs have raised the costs of production for goods throughout the manufacturing sector. That has had adverse effects across the manufacturing spectrum with particularly acute problems in industries that have also seen their revenues squeezed by foreign competitors who now have access to cheaper inputs and can offer their products at lower prices than can U.S. firms. Meanwhile, U.S. farmers have been the primary targets of retaliatory tariffs because agriculture is presumed to carry disproportionate political weight in Washington, which might be leveraged to end the madness of the trade war. Instead, Trump is doubling down on his plan to buy their quiescence. But the tab is falling on manufacturing. And their disquiet could spell big trouble for Trump’s reelection bid.

The answer is to rescind all the tariffs imposed since 2018 and begin the process of digging industry and agriculture out of holes that never should have been dug.