The Trade Deal China Wants Isn’t Just Bad, It May Be Illegal

In talks earlier this month, Chinese negotiators reportedly offered to eliminate their country’s bilateral trade surplus with the U.S. by buying $1 trillion in American goods over the next few years. It’s unclear whether they were serious, or whether U.S. producers could even meet the additional demand. The biggest problem with such a transactional deal, though, is one no one’s talking about: It would most likely be illegal.

Because China and the U.S. are members of the World Trade Organization, they each have a legal obligation under the WTO treaty not to favor imported products from one WTO member over like imports from any other WTO member. This is the most-favored-nation rule of nondiscrimination — one of the foundations of the rule-based world trading system. Any trade advantage granted to a particular country must be extended immediately and unconditionally to all other WTO members.

The U.S.-China talks reportedly remain stuck on more difficult issues: restructuring the Chinese economy to make it more market-oriented and preventing the theft and forced transfer of intellectual property. A deal that tackled those challenges most likely wouldn't present any WTO-related problems. Presumably, any restructuring by China of its subsidies, trade licensing requirements and other market-access restrictions would be done in ways that would benefit all WTO members alike, not just the U.S.

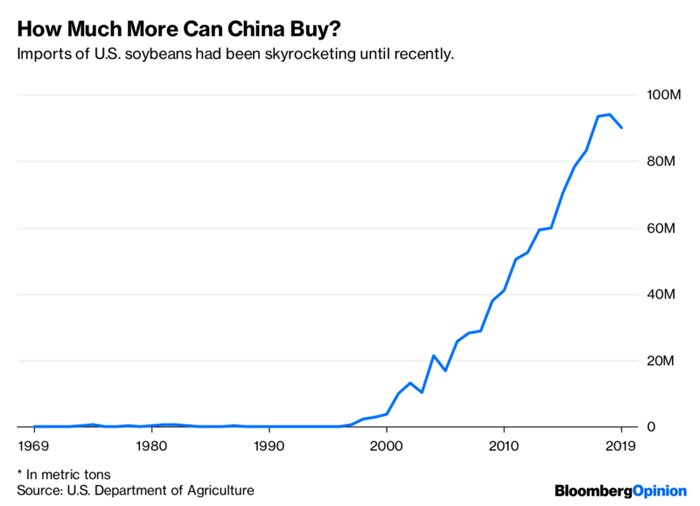

But, any deal that solely benefits American products and producers through certain transactions in certain specific sectors of trade could well violate the WTO treaty. For example, a pledge by China to increase its imports of soybeans from the U.S. by some stated annual amount most likely wouldn't involve increasing the total amount of Chinese soybean imports or forcing Chinese to consume more soybeans. Instead, importers would simply shift their purchases from other countries — say, Brazil — to the U.S.

Such a deal would give U.S. soybeans a trade advantage over Brazilian soybeans and would thus be a violation by China of its most-favored-nation obligation to Brazil. The Brazilians, probably in concert with other soybean-exporting countries, would surely take legal action against China in the WTO — and win. An adverse judgment would confront China with the choice of either reneging on its deal with the U.S. or facing lawful trade sanctions authorized by the WTO.

Under such sanctions, China would lose economic benefits that Brazil and any other complaining countries had previously granted to it under the WTO treaty, in other sectors of their trade with China. Such sanctions have been levied often in the WTO-based trading system and could add up to billions of dollars in lost trade annually.

Are the Chinese truly willing to invite such consequences in order to try to placate U.S. President Donald Trump? It would be far better for leaders in both Beijing and Washington, D.C. to focus less on a transactional and temporary payoff to the U.S. and more on the longstanding concern at the heart of their confrontation: the many ways in which both countries discriminate unfairly against the imports of the other in a trading relationship that is vital not just to them but to the whole world.