Dear Capitolisters,

While we were away, President Joe Biden was in Asia announcing his new “Indo-Pacific Economic Framework for Prosperity” (IPEF) with 12 other countries (Australia, Brunei, India, Indonesia, Japan, South Korea, Malaysia, New Zealand, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam). The IPEF’s goal, per the White House, is to “strengthen our ties in this critical region to define the coming decades for technological innovation and the global economy” and to counter China’s economic and geopolitical influence in the region. The IPEF’s details remain fuzzy—it has four general (vague) pillars (connected economy, resilient economy, clean economy, and fair economy), and members haven’t even committed to undertake all of them—but what is clear is what the IPEF won’t be: a trade agreement. That’s a big missed opportunity for the United States and these other nations, but also a great opportunity for us to discuss perhaps the single most boneheaded U.S. policy move of the last decade: abandoning the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) free trade agreement.

That Was Then …

Originally started during the waning days of the Bush administration, the TPP was expanded in the Obama years to cover 12 nations: Australia, Brunei, Canada, Chile, Japan, Malaysia, Mexico, New Zealand, Peru, Singapore, Vietnam, and the United States. After a lot of foot-dragging on the U.S. side, the comprehensive agreement—covering the usual FTA issue areas (goods, services, agriculture, investment, intellectual property, digital trade, etc.)—was concluded in October 2015 and signed in February 2016. The TPP had several core objectives:

-

Economic benefits. Most obviously, reducing trade barriers among the TPP parties was expected to do what trade liberalization/expansion typically does: increase efficiency, productivity, and economic growth among participating countries. As my Cato colleague Clark Packard noted a few weeks ago, these gains were estimated to be small but significant for the United States, raising real incomes by tens of billions of dollars per year (or more, depending on which estimate you use). Consumers, of course, were also going to be big winners, as were American farmers who’d break into then-closed export markets. And similar gains were expected for other TPP parties.

-

Trade rules benefits. TPP was also expected to advance new trade disciplines on “modern” issue areas like digital trade, industrial subsidies, and state-owned enterprises—issues that weren’t covered in older agreements like mid-1990s NAFTA or the World Trade Organization. Ideally, these rules would be handled at the latter (and thus applicable to more than 160 nations), but a decade-plus of WTO stasis pushed the United States and others to seek alternative venues to write the rules and eventually “multilateralize” them at the WTO after enough nations accepted the disciplines in smaller agreements like TPP. China, again, loomed large: The new rules targeted a lot of China’s problematic “state capitalist” trade practices, so Beijing—and a few other state-led economies—would naturally oppose such changes at the WTO (where consensus reigns). Thus, TPP allowed signatories to avoid this problem and set a high, “American-made” bar for any eventual Chinese accession to the agreement or for getting WTO members to pressure China into accepting the disciplines on the multilateral level.

-

Geopolitical benefits. Most everyone understood, however, that TPP was about more than just trade rules and economics (indeed, several TPP partners already had FTAs with the United States). Instead, it was a major foreign policy initiative designed to counter China’s growing influence in the Asia-Pacific region in at least three ways: First, it would provide TPP parties with an alternative market (the United States) as large and influential as China’s. Per the “gravity model,” countries tend to trade with large, nearby economies, and TPP’s elimination of trade restrictions among the participants was intended to offset (though probably not entirely) China’s massive “gravitational pull” in the region. It’d also help to reorient Asia-Pacific supply chains away from China and toward the TPP parties (including the U.S.). Second, the TPP was intended to serve as a peaceful forum for regional cooperation, consultation, and dispute settlement—again an alternative to the slower, bigger WTO. Finally, TPP was intended to be a platform for more nations to join on—especially close U.S. allies and trading partners like South Korea, Thailand, and others. Doing so would not only bring additional economic benefits for the United States, but increase the attractiveness and impact of the “TPP supply chain.”

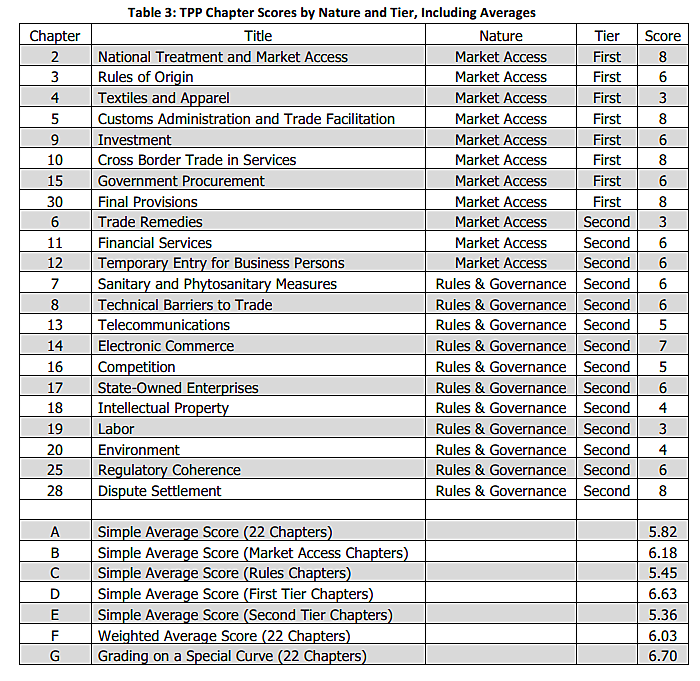

Of course, TPP wasn’t perfect. For starters, regional trade agreements are a “third best” option for liberalizing trade (the order: unilateral, then multilateral, then regional, then bilateral). They’re also negotiated on economically ignorant, mercantilist terms (exports good and imports bad) that can undermine longer-term support for “real” free trade, and—because all trade agreements must be approved by Congress—they’re sure to have a few porky, even protectionist terms. TPP, as documented in Cato’s intensive, chapter-by-chapter review of the agreement, certainly had some of these terms but wasn’t nearly as terrible as critics claimed: 15 chapters liberalized trade (a score above 5 in the table below); five were protectionist (below 5); and the most important (“Tier One”) chapters were net liberalizing on average (6.63).

Criticism of certain TPP terms—especially on textiles and intellectual property, in my opinion—was surely warranted. However, as we documented in the chapter reviews, much of it was overblown, and some was just tinfoil-hat-level nuts. Furthermore, holding out for “true free trade” would throw the liberalizing baby out with the protectionist bath water—all while waiting for a “pure” victory that was almost certain to never materialize. We thus decided that the agreement, while flawed, warranted support and ratification: “Considered as a whole, the terms of the TPP are net liberalizing—it would, on par, increase our economic freedoms.”

And this, it should be noted, didn’t even get into the geopolitical issues (which Cato scholars frequently noted elsewhere).

… This Is Now

President Trump, of course, didn’t listen to us—or the numerous other folks on the left and right with similar views (and reservations)—and instead abandoned the TPP on his first day in office. As we’ll discuss in a sec, this was a colossal mistake in retrospect, but it’s important to note at the outset that the blame for TPP’s failure shouldn’t fall to Trump alone. For starters, the Obama administration slow-walked negotiations for years, pushing the deal’s completion into the always contentious 2016 presidential election season, and President Obama rarely used his bully pulpit to champion the deal once it was completed. Meanwhile, congressional Republicans and their allies—motivated by partisanship, kooky theories, and Donald Trump’s meteoric rise in 2015—abandoned their traditionally strong support for FTAs and the “trade promotion authority” procedural rules needed to get them through Congress. This sudden shift made TPP a heavier lift for Democrats, who were already trade-skeptical (thanks, unions!) and were made more so by protectionist Bernie Sanders’ presidential run—a run that pushed Hillary Clinton to renounce her own support for TPP (after fierce internal debate by her advisers). Thus, by late 2016 the agreement was on life support—Trump just pulled the plug a few months later.

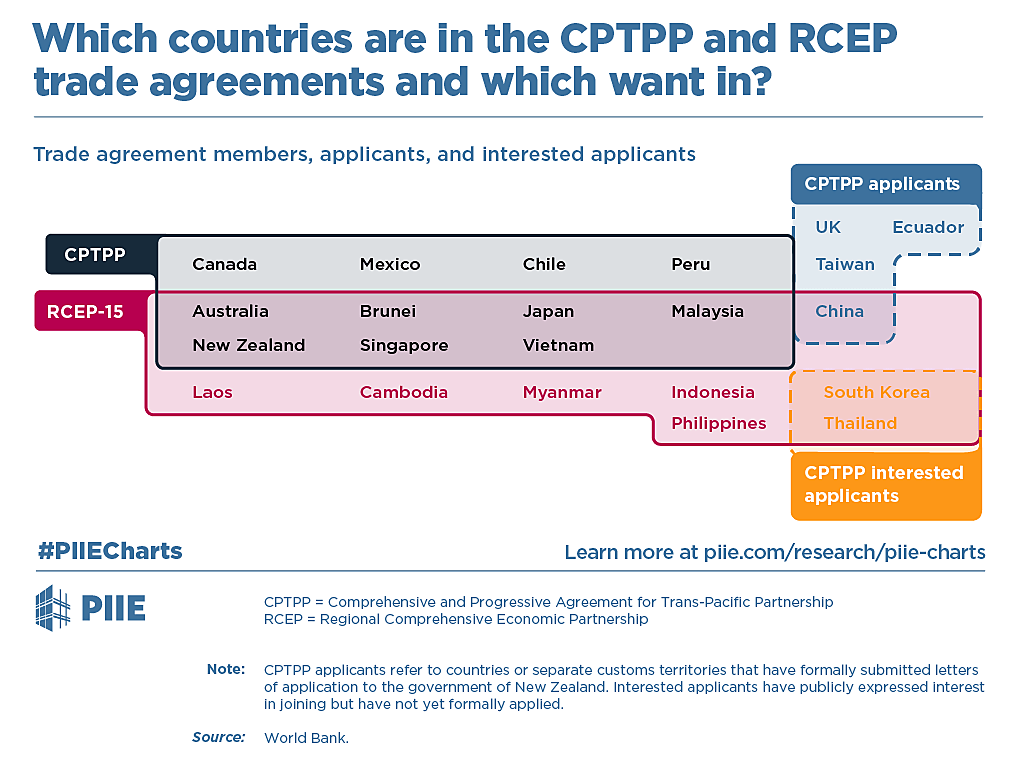

Since then, we’ve unfortunately re-learned why people supported TPP in the first place. On the economics, the United States not only lost out on new liberalization but was actually made less competitive when the rest of the TPP parties moved on without us and inked the (terribly named) Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP). That deal, it should be noted, actually nixed some of the TPP terms that American critics (including us at Cato) found to be problematic—such as overly protectionist intellectual property restrictions and rules that let private investors effectively sue governments for infringing on their investments. And its ratification, as Packard notes, left the United States on the outside looking in:

American consumers, including domestic firms relying on imported inputs, face higher prices and fewer choices than their peers in CPTPP/TPP countries, while exporters face higher barriers in reaching new consumers than their competitors in the trade bloc. Indeed, a study from the Canada West Foundation found that U.S. withdrawal from TPP likely cost American exporters $3.1 billion per year in lost sales.

As Cato’s Colin Grabow recently noted, a separate analysis “calculated that the TPP/CPTPP’s net impact on the United States had swung from a $131 billion gain to a $2 billion loss.” Another found U.S. farmers might lose almost $2 billion in annual export sales—a prediction unfortunately backed up by subsequent experience.

Making economic matters even worse, China subsequently inked its own regional trade deal—the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP)—with many of the TPP parties and several others in the region. That agreement is less comprehensive than CPTPP but still liberalizes trade somewhat (especially for goods), thus helping China increase its economic growth and already-strong “gravity” in the region.

This means not only closer integration among RCEP economies, but also diverting transactions away from the United States and toward China and RCEP’s other members. Thus, as Grabow notes, a recent U.N. Conference on Trade and Development report “found that RCEP will shrink U.S. exports by over $5 billion as trade is diverted away from U.S. firms and toward foreign competitors subject to lower tariff rates under the agreement.”

It’s thus no surprise, then, that the Trump administration spent its entire tenure trying to “humpty-dumpty” the TPP via smaller trade agreements, such as Trump’s NAFTA remake (which cut-and-pasted a lot of TPP’s terms and was more protectionist in several key areas like autos trade) and the “mini-deal” with Japan, which covered only goods. On the latter deal, Grabow explains that it was “presented as the prelude to a more comprehensive agreement (which never happened), and that “the market access improvements realized from the agreement—mostly on agriculture and industrial goods—were still inferior to what would have been gained via the TPP.” And, of course, the Trump team missed out on increasing trade with other TPP parties, such as the large, up-and-coming Vietnam and Malaysia or other nations seeking to join CPTPP, such as Thailand and the Philippines.

Losing out on those economic gains also has geopolitical importance. In particular, souring U.S.-China relations and China’s own internal problems have motivated many companies to look to alternative markets like Vietnam—a shift that could have been encouraged by TPP.

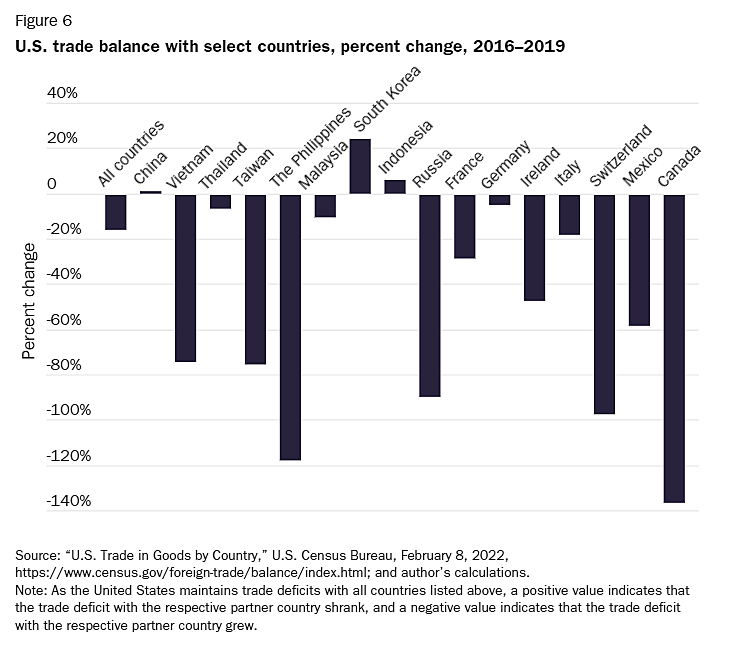

Indeed, as I documented in a recent paper, changes in various bilateral trade balances since Trump’s China tariffs were enacted show how many TPP parties stepped into the breach left by declining U.S.-China trade—a strong indication that TPP could have motivated an even bigger shift away from China (for us and the TPP nations) without the pain and uncertainty of those tariffs.

Instead of encouraging these moves through TPP, the Trump administration actively fought them—such as when it opened new “Section 301” and currency investigations of Vietnam (and, of course, the president’s constant tariff threats against Canada, Mexico, and the European Union).

Dumb, dumb, dumb.

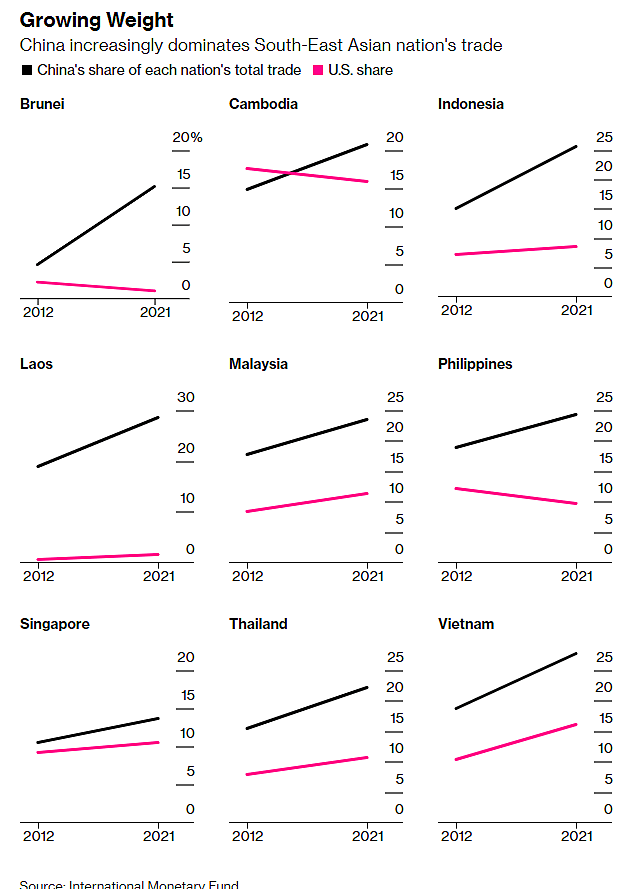

Meanwhile, China’s ties with Asian nations are—fueled by RCEP and that pesky gravity—growing relatively more important as compared to the United States:

The Wall Street Journal adds that “Trade between China and countries in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations… has more than doubled in the past decade.” The United States still matters for these countries, but we’re losing ground—especially as a source of imports in some of these less-open Asian economies.

It’s thus no surprise, then, that IPEF parties (including many in the CPTPP) have stated in private and in public that all those “pillars” and stuff are fine but will do little without a real, comprehensive trade agreement backing them up. And, as Politico explained earlier this week, the CPTPP is the obvious play:

[New Zealand Prime Minister Jacinda] Ardern has also been a vocal proponent of Biden making a return to the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership….

“If the United States is looking to engage in our region economically, then that is the place to do it,” Ardern told reporters last week after meetings on Capitol Hill. She called CPTPP the “gold standard” just two days after Biden’s big economic framework kickoff. That’s a message she may well carry into her meetings today with Biden and Vice President Kamala Harris.

Ardern is not alone in her advocacy. Other key U.S. allies in the Indo-Pacific, including Australia, Singapore and Japan, have also expressed a desire for the U.S. to rejoin CPTPP. And at the recent US-ASEAN Summit in Washington, some Southeast Asian leaders also expressed a desire for Biden to do more to increase trade.

Many of those same Southeast Asian leaders are seeking to join the CPTPP (just as it was originally intended), as is the United Kingdom and even China. That last bit is more of a troll than reality, but—regardless—all of this is precisely what the TPP was intended to do: grow to cover most of the region and push China to adopt and conform to tougher, modernized trade rules.

As it currently stands, however, China’s increasingly influencing the rules with the help of the weaker RCEP—and, as Packard notes, the United States’ own retreat from global trade:

CPTPP/TPP withdrawal also signaled a dramatic shift in U.S. international economic leadership and damaged its credibility. It was the first trade agreement that the United States negotiated to completion and then failed to ratify and implement. That decision, coupled with the Trump Administration’s reckless trade wars with longstanding allies, sent a distinct message to the rest of the world that the United States was turning inward and could not be trusted to defend the rules and norms it carefully cultivated over the last 70 years. Few could be happier with this outcome than Xi Jinping.

Thus, as Grabow explains, American companies are seriously concerned that China is taking over not only economically but also legally:

[A] recent Wall Street Journal piece points out that U.S. inaction on trade liberalization has handed a possible opportunity to China: “Beijing’s pro‐trade steps have fueled concerns among American businesses and close allies. They worry that the U.S.’s absence in regional trade agreements gives Beijing an opening to establish its leadership in setting rules and standards for trade and economy, particularly in emerging technologies such as artificial intelligence and digital trade.”

Without an actual trade agreement (and new access to the U.S. market), “the United States will be competing for influence with China with one hand effectively tied behind its back. While Beijing offers improved access to its vast market through its participation in RCEP—and possibly the CPTPP—Washington will have few obvious enticements with which to sway other countries toward adopting its preferred set of trading rules and standards.”

Alas, what could’ve been.

The Politics of Inaction

IPEF, unfortunately, won’t change this troubling situation—nor will a separate initiative announced today with Taiwan. The reason, as Politico notes, isn’t economics or foreign policy but simple politics:

Biden’s top trade officials are still haunted by voters’ rebuke of trade deals in the 2016 election cycle. They have turned their thumbs down to the idea of joining the CPTPP, especially in its current form, and cited political backlash as a key reason their economic framework does not include much-desired market access provisions.

Policy aside, this strikes me as politically wrongheaded for numerous reasons. First, because the vast majority of voters have short memories, don’t care much about trade policy and instead take their cues from whoever’s president, and certainly don’t sweat trade agreement details, making a few superficial changes to CPTPP text—beyond those already made—could make rejoining the agreement more politically palatable, even for some of the people who were justified in their original TPP criticisms. Indeed, this is precisely what President Obama did when he superficially renegotiated the once-controversial U.S.-Korea FTA before getting Congress to approve it by wide margins in the House and Senate. The bully pulpit can be effective—if the president is willing to use it.

Second, the last few years of failed tariff wars, CPTPP/RCEP developments, and China’s continued regional rise have made the economic and geopolitical impetus for CPTPP far clearer than what it was in 2016. Barely a week goes by these days without another concrete example of why it’s so important for the United States to increase economic engagement with Japan, Vietnam, New Zealand, and others in the AsiaPac region. And these nations are basically begging us to do so! President Biden thus has plenty of new ammunition to push CPTPP support (and criticize CPTPP opponents) that President Obama never had—and it all clearly fits with pre-existing White House/national priorities like “countering China” and “fixing supply chains.”

Finally, there is increasing bipartisan recognition that TPP withdrawal was a foolish move, and that re-engagement is needed to achieve key U.S. economic and geopolitical objectives:

Even former Trump staffers see [CPTPP avoidance] as a mistake. “I still don’t understand why they didn’t put market access on the table,” said Kelly Ann Shaw, a former Trump senior trade adviser who is now a partner at law firm Hogan Lovells. “It diminishes the credibility in the eyes of our trading partners about how serious the administration really is about negotiating new rules that result in binding commitments.”

Though Trump pulled out of what was then the Trans-Pacific Partners, Shaw said it would be a “huge mistake” for Biden not to try to get back in. “TPP was a flawed agreement, and the politics weren’t there to pass it in Congress at the time,” Shaw said. “So, clearly the agreement would have to be renegotiated. But I think that that is possible. And I think that other CPTPP countries want us to come back to the negotiating table.”

Republicans on the House Ways and Means Committee also just called for deeper economic engagement than that offered in the IPEF, and senators like John Cornyn (along with Democrat Tom Carper) have been banging the “rejoin CPTPP” drum for a while now. Outside the Capitol, conservative scholars are also speaking up:

One can and should ding these folks for quieting down during the Trump years, but a lot of them seem to be back on board now. It’s a start.

None of this matters, of course, if the White House doesn’t believe it—or it Biden is simply unwilling to expend the political capital needed to prioritize CPTPP above other domestic priorities (and confront the inevitable congressional skeptics in the process). Given IPEF, that definitely seems to be the case right now, regardless of the painful lessons that TPP keeps teaching us.