Most economists and commentators now agree: a big reason for Vice President Kamala Harris’s defeat in Tuesday’s presidential election was high inflation delivering higher prices.

I’ve written extensively on why the public hates inflation so much. But the election result is producing disagreement about what the policy implications should be for Democrats. Three responses being pushed, in particular, would be exactly the wrong lessons for them to learn, at least from an economic perspective.

Macroeconomic Policy Was Fine, It Was The Microeconomic Policy That Was Faulty (Liberalizing Version)

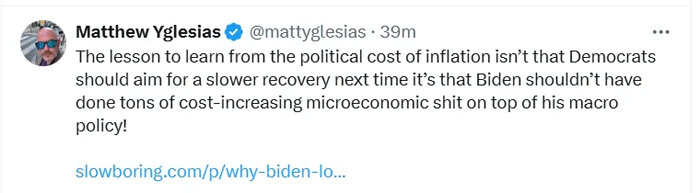

Matt Yglesias tells Democrats (to paraphrase): ‘“you were right to “run the economy hot” by supplementing extensive monetary stimulus with huge budget deficits. What you then got wrong was imposing a bunch of cost-inflating mandates that constricted the supply-side of the economy as conditions for your subsidies.”

To which I’d say: look, I am as in favor of using concern about high prices to push for supply-side reform as anyone else. But while these policies, like toughening Davis-Bacon laws or Buy American provisions, raising tariffs, or keeping the Jones Act, undoubtedly raised certain prices and maybe even the price level by making supply less elastic, their effect in raising inflation since 2021 has been incredibly marginal, at most.

So, yes, let’s reverse all these bad policies anyway to help lower the costs of essentials and make the economy more efficient, but that wouldn’t have stopped the recent price level surge, which was, in fact, overwhelmingly driven by too much stimulus. Microeconomic fiddling is no match for those macroeconomic forces.

Macroeconomic Policy Was Fine, It Was The Microeconomic Policy That Was Faulty (Greedflation Version)

The Greedflationist narrative is similarly microeconomic but with the opposite conclusion. Most of its proponents see inflation as having been driven by, first, cost shocks owing to the pandemic and Ukraine war, and then exacerbated by corporate collusion, market power, and business shrouding. To the extent they mention macroeconomic stimulus, most think it was appropriate or necessary, somehow driving a strong jobs recovery and real GDP but having absolutely no effect on the price level.

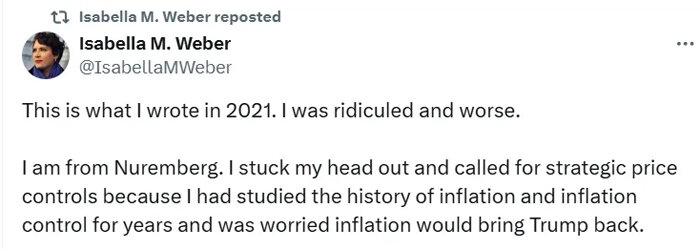

Their takeaway is that the public’s hatred of inflation shows why the Biden-Harris administration should have been even more aggressive in promising price controls to “protect” voters from price hikes. It apparently wasn’t enough that Harris promised an “anti-price gouging law” for basic groceries, a national rent control proposal, and a host of new restrictions on “junk fees.” No, Isabella Weber, Hal Singer, and the gang think she should have made these more central to her campaign (though Singer was praising the campaign for going hard on it before election day?).

Maybe their psephology is correct (though I doubt many Latinos whose families have fled socialist states would emphatically welcome the call for price controls). Regardless, the economics is terrible. Price controls would have crystallized shortages, product quality declines, and extensive black markets. They have a record of failure so blatant, and are so overwhelmingly opposed by economists, that this “solution” is little more than a comfort blanket for progressives.

Next Time We’ll Have To Accept Vastly Higher Unemployment

Democrat economist Betsey Stevenson thinks that the unfortunate takeaway of Harris’s defeat is that voters dislike inflation more than elevated unemployment.

The economic model she has in mind here is a sort of simple Phillips curve: that, in the short-term at least, all that macroeconomic stimulus drove high demand which delivered both high employment and above-target inflation. That this was so politically unpopular shows that voters would have preferred less fiscal and monetary stimulus, higher unemployment and more stable prices, no?

I agree with her that given that everyone is affected directly by inflation, policymakers underestimated its unpopularity. But Stevenson overreaches with a faulty model determining her conclusion. Tight labor markets don’t “cause” inflation. Unemployment does not cure it. Both tight labor markets and inflation can be shared consequences of excessive spending driven by too much stimulus, but one needn’t imply the other.

The very fact that there has been less fiscal and monetary economic stimulus in recent years and that spending growth has fallen without a big spike of unemployment as inflation has tumbled, shows that, provided the slower growth of total spending is anticipated, there’s no reason why less stimulus need cause mass unemployment. In other words, there’s an alternative world where there was far less monetary and fiscal stimulus in the latter stages of the pandemic, the economy recovered and unemployment remained pretty low, but we simply saw lower inflation.

It will be hard to accept this lesson. The mythology built up by Democrats since the financial crisis is that pushing the demand accelerator is a necessary precondition of good macroeconomic outcomes. But we’ve just run the experiment in both directions over four years! It’s time to update some priors.