Among the most common economic justifications for tariffs today is that they’re needed to shrink a U.S. trade deficit that has long cost us jobs and dragged down economic growth. On both the left and the right (including the current occupant of the White House), trade balances—both overall and with specific countries like China or our new mortal enemy, Canada—are treated as a scoreboard for quickly judging the success or failure of U.S. trade policy and globalization more broadly. And seemingly every time the government releases the latest trade balance figures, at least one business journalist—and usually many more—will earnestly write that the U.S. trade deficit “improved” (shrunk) or “worsened” (increased), and that the deficit is a drag on economic growth.

Yet little that I just wrote is actually correct.

Given all (*gestures around wildly*) that’s going on in the news these days—much of it linked to the U.S. trade deficit—and that Capitolism has never devoted an entire column to the issue, it’s past time we remedied that, umm, deficit with the things every person, especially policymakers in Washington, should know about the U.S. trade deficit.

A Trade Deficit Is a Symptom, Not a Disease

A trade balance is not a complicated concept; it’s simply the difference between what a nation exports—both goods and services—and what it imports. If the former is greater than the latter, you have a surplus. If the latter is greater than the former, you have a deficit.

If only the discussion could end here.

Of course, the discussion doesn’t end there, and instead trade balances are trotted out to justify all sorts of protectionist trade policy—including today’s tariffs—on the grounds that persistent deficits are a disease killing both American jobs and growth and thus demanding strong government medicine. This common assertion, however, fails on the facts and the economics.

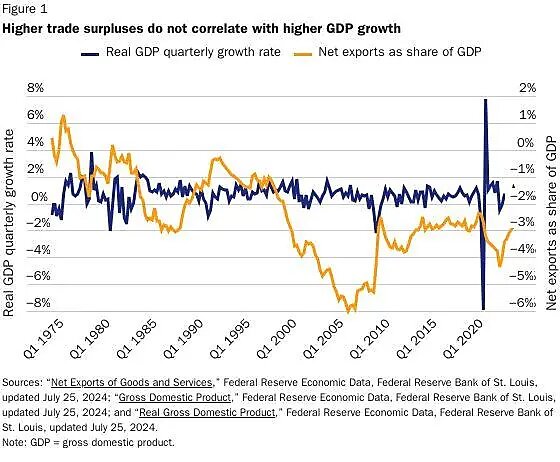

For starters, there’s little obvious connection between the U.S. trade balance and economic output (gross domestic product). As shown in the chart below from a recent Cato essay on the trade balance, the relationship between higher trade surpluses (or smaller deficits) and higher GDP growth is practically nonexistent. Economist Don Boudreaux and former Sen. Phil Gramm dug through additional periods in a recent Wall Street Journal column and concluded that “[b]etween 1890 and 2024, it is impossible to find a statistically significant correlation between America’s trade balance and its economic growth.”

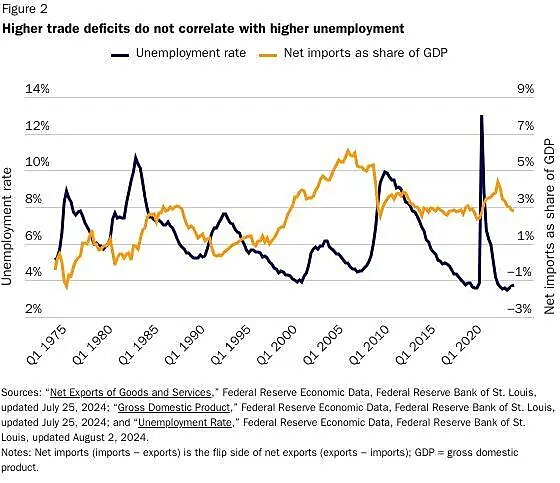

On employment, meanwhile, the relationship is weakly counter to the conventional wisdom: when the trade deficit goes up, the unemployment rate tends to go down. This doesn’t mean, of course, that a higher trade deficit causes lower U.S. unemployment, but it should at least give us pause about trade deficits killing jobs—and put the burden of proof on those claiming that it does.

Other metrics, such as U.S. manufacturing output, similarly fail to show a solid connection to the trade deficit.

This non-relationship makes sense once you understand that the trade deficit is driven not by trade policies but by nations’ overall levels of savings and spending (i.e., investment and consumption). National income—created by investment, production of goods and services, and exports—is used either to consume/invest or to save. Nations that, in the aggregate, spend more than they save will import more than they export (i.e., run a trade deficit), and their investors (or banks) will finance this consumption with capital from abroad. Trade surplus nations face the opposite situation.

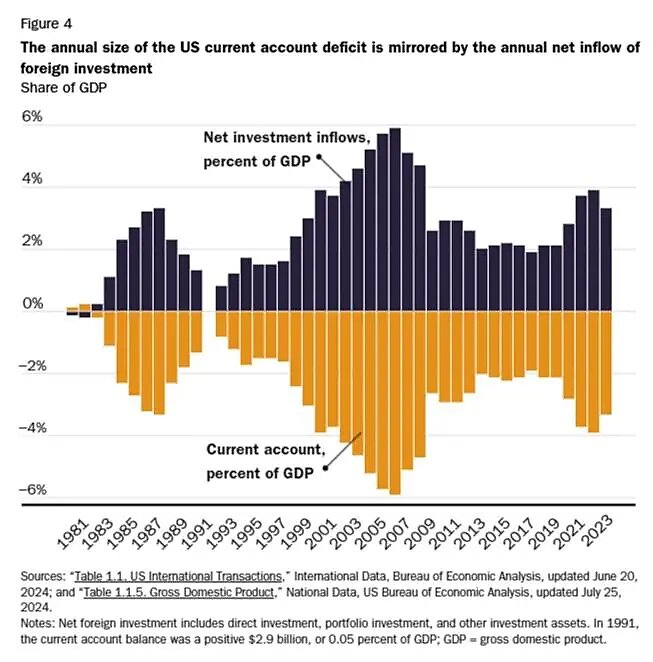

You can see this dynamic play out in the U.S. government’s “balance of payments” data, which records all international transactions involving the United States: the “current account” measures trade and income flows between the United States and the rest of the world (and is mostly the trade balance we see reported in the news) and is mirrored by the “capital account,” which covers foreign investment and other financial transactions. In each case, a current account deficit/surplus will always be accompanied by a net inflow/outflow of foreign investment capital in approximately the same amount. Here’s the telling chart:

The other critical point here is that aggregate data, like those in the chart above, mask that national income, trade, spending, and investment are actually the product of billions of transactions by millions of individuals and firms acting independently of each other, instead of—except in somewhat rare circumstances—government entities. Put simply, the trade balance isn’t really about one nation trading with others, even though that’s always how it’s described—and even shown in all my pretty charts.

Understanding these facts leads us to several important lessons about trade balances:

- First, a nation’s trade balance isn’t a cause of bad or good things in an economy (and thus a “bad” or “good” thing to be fixed/encouraged), but instead an indicator of the macroeconomic factors affecting residents’ spending and saving decisions and thus the nation’s overall level of savings and investment/consumption. These factors include government policies (e.g., taxes or entitlements that encourage immediate consumption over savings, policies that improve a nation’s attractiveness to global investment, etc.) and overall government indebtedness (spending more than it takes in). But they also include noneconomic things like culture and demographics: Countries with a relatively young population typically spend more than they save and need domestic investment capital, so they should expect net capital inflows and trade deficits regardless of government policy (within reason!).

- Second, one can’t judge whether a trade deficit is a problem without considering its underlying macroeconomic causes and how related foreign capital inflows are used. If those inflows are caused by a nation’s young population and its attractiveness as an investment destination—and if they’re invested productively in things like education, housing, or research—then the resulting trade deficit would be benign. If, on the other hand, the trade deficit is primarily driven by an elderly citizenry’s debt-financed consumption and by profligate government spending, then it could be more of a concern. In either case, however, the trade deficit remains a symptom, not a cause, of a nation’s underlying economic issues.

- Third, any real attempt by policymakers to fundamentally change the trade balance must somehow address these macroeconomic factors and thus alter individual decisions and, in turn, the overall balance between national savings and investment. Tariffs or trade agreements simply won’t do the trick.

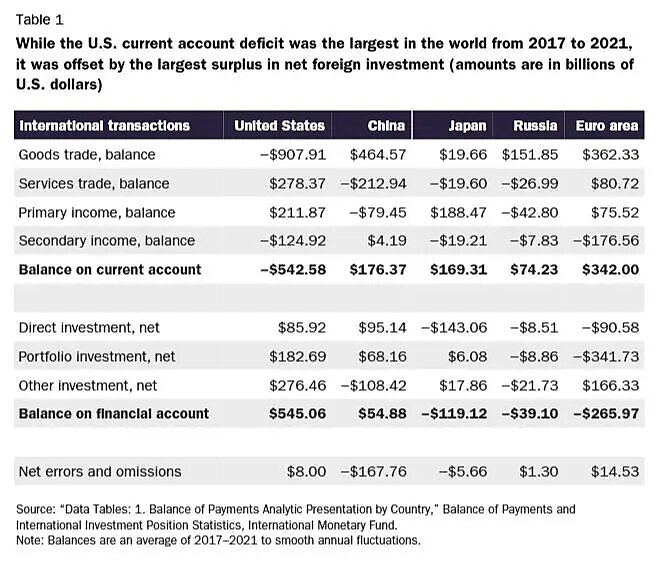

Applying these factors to the United States reveals why most serious economists see our current trade deficit as benign. We have a relatively younger and faster-growing population than other Western nations, and we tend to save a smaller share of our income than they do. We’re also a very attractive destination for capital from abroad, whether as investment in private companies (foreign direct investment) or our high-performing stock markets, as bank deposits or loans (“other investments” in the table below), or as purchases of real estate or government debt (which has long been seen as a “safe haven” for investors). The U.S. dollar’s role as the world’s “reserve currency”—still about 60 percent of central bank reserves—also boosts global demand for (and the value) our dollars, and the federal government continues to spend more than it takes in.

Here’s how it all breaks down and compares to other countries:

Aside from our government’s runaway deficit spending, none of the drivers of the U.S. trade deficit is necessarily “bad” for the U.S. economy, and many of them—portfolio investment, foreign direct investment, etc.—are objectively good and indicative of a thriving economy. (And before you ask, U.S. household debt is mostly home mortgages and has actually been trending down since the mid-2000s, while corporate debt has been basically flat for decades.)

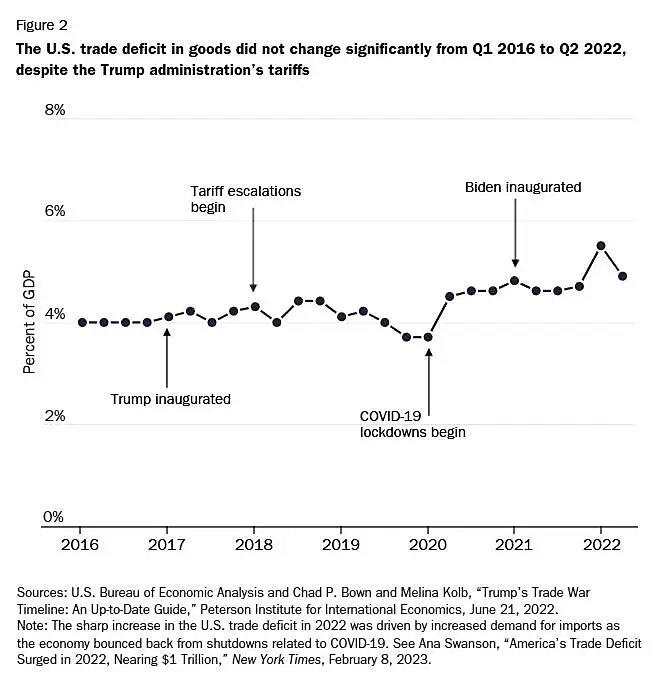

This also explains why no serious economist thinks tariffs or trade deals will significantly reduce, no less eliminate, the U.S. trade deficit. As I explained last September, “Tariffs can reduce both imports and exports, reducing a nation’s overall level of trade but leaving its trade balance unchanged in the long run”—a conclusion supported by research on dozens of different countries and the United States’ own experience during the first Trump term:

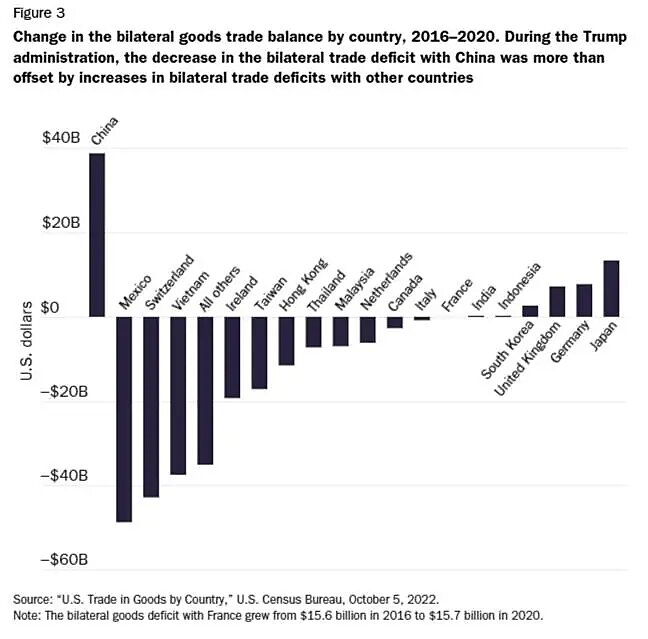

Instead, all those tariffs simply shifted the source of the U.S. trade deficit, not its size—just as economists predicted.

None of these general lessons, it should be noted, are new or surprising—they’re precisely the conclusion of the bipartisan U.S. Trade Deficit Review Commission (TDRC) decades ago.

A Trade Deficit Isn’t a ‘Drag on Growth’

The next big and related mistake about trade deficits is that they reduce U.S. economic growth. The first chart above should raise doubts about this conclusion, yet we hear it constantly in the press every time the latest trade balance figures are released (and from Trump adviser Peter Navarro almost as often).

But this claim stems from two fundamental errors:

First, advocates misunderstand how the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) calculates GDP and what the calculation actually means. The standard calculation is as follows:

GDP = C + I + G + (X − M)

Where C is consumption, I is investment, G is government spending, and (X − M) is exports minus imports (aka “net exports”).

Economic simpletons see this identity and assume that an increase in the trade deficit (i.e. a decrease in “net exports”) causes a real reduction in U.S. economic output—a mistake to which BEA itself contributes by often calling imports “a subtraction from the calculation of GDP.” However, the agency is describing only an accounting technique, not a real economic phenomenon. Imports, by definition, are not part of gross domestic product. Because BEA can’t discern the exact import content of goods and services produced in the United States, it simply adds up total domestic consumption in a given period and then subtracts imports, assuming that what’s left over must have been produced domestically (i.e., GDP). If BEA didn’t subtract imports from the GDP calculation, it would wrongly attribute to American producers stuff that was actually produced abroad. But this doesn’t mean that BEA is saying imports actually reduce U.S. economic output—it’s just how they calculate GDP.

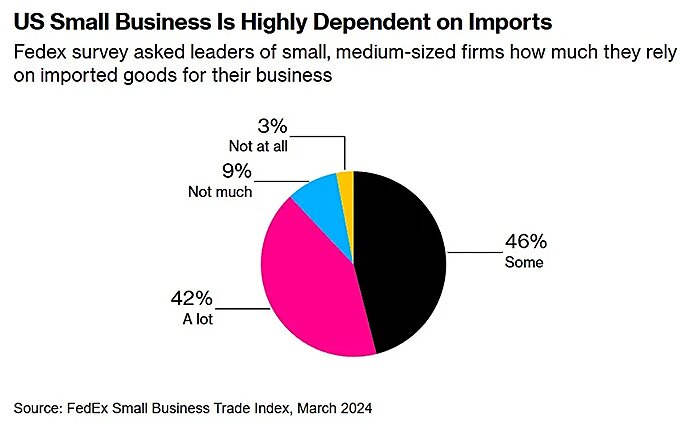

And that gets to the second error: the assumption that imports are always a 1‑to‑1 substitute for domestic production. In some respects, that’s true: If you buy a car made in South Korea, you don’t buy one made here. But in many (if not most) cases, the assumption is false because imports often complement—and thus boost—domestic production of goods or services. As we’ve discussed, for example, about half of U.S. imports are intermediate goods, raw materials, and capital equipment that U.S. manufacturers use to make their final products and remain globally competitive. Imports of these inputs can therefore increase domestic manufacturing output, rather than subtract from it. Going back to cars, for example, we discussed late last year that “an expanding U.S. trade deficit in automotive goods has … long coincided with gains in domestic output and production capacity.”

Other imports can support the production of domestic services. Goods made offshore and then imported by “factoryless” manufacturers in the United States let them expand their domestic work in research, design, marketing, and other services. Imported lumber, nails, and other construction materials boost American homebuilders. Imported laptops and smartphones let U.S. professional or educational services expand. Imported drugs and medical goods can help hospitals. The list goes on and on.

Even imported consumer goods can boost U.S. output. Companies tasked with moving or selling imported items—in wholesale trade, retail trade, and transportation and warehousing —generate trillions of dollars of additional U.S. economic output. By reducing retail prices, moreover, imports can free consumer dollars for spending on American goods and services. And, as already noted, dollars spent on imports quickly return to the United States as either investment in U.S. assets or purchases of exports, both of which contribute to economic growth.

Put it all together, and the “drag on growth” narrative collapses.

A Trade Deficit Doesn’t Reflect a ‘Loss of American Wealth’ or a ‘National Debt’

It’s similarly wrong to assert—as our president often does—that the U.S. trade deficit represents a loss of wealth for the United States or some kind of national “debt.” For starters, this ignores that dollars we send abroad to foreigners buy us real goods and services that we value (or else we wouldn’t buy them), and that—as discussed above— those same dollars eventually return to the United States as investment in the U.S. private or public sector (by mostly unrelated people). Some call the latter a “debt” we Americans must repay, but in many cases—portfolio investment, foreign direct investment, real estate, and basically anything else that isn’t actual public debt—that’s not really true. Corporate debt, for example, is owed by shareholders and employees of the company at issue, not by you and me. Foreign purchases of equity (stocks), property, or even entire U.S. companies isn’t “debt” at all—and can benefit most Americans and the nation if the investment spurs more hiring/production/innovation, causes stocks to rise, or causes similar, American-owned assets (e.g. property) to appreciate too. It’s not zero-sum.

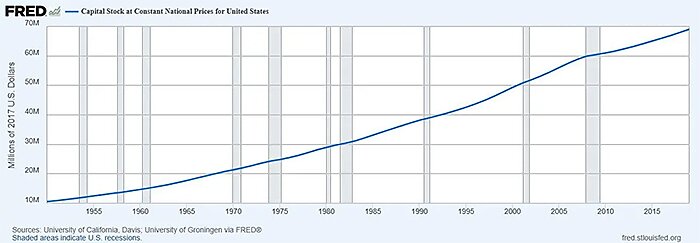

Evidence backs up the theory. Despite decades of uninterrupted trade deficits:

- The inflation-adjusted U.S. capital stock has steadily risen and was at its all-time high right before the pandemic (2020–25 figures are not yet available):

- Per a 2024 Congressional Budget Office report, “Adjusted for inflation, the wealth held by families in the United States almost quadrupled between 1989 and 2022, rising from $52 trillion (in 2022 dollars) to $199 trillion, at an average rate of about 4 percent per year.”

- Per economist Don Boudreaux, the average inflation-adjusted net worth of an American household in 2019 was 46 percent higher than it was in 1999 (when China got most favored nation trading status) and 118 percent higher than in 1987. Elsewhere, he adds that the real net worth of nonfinancial corporations in the United States last year was 73 percent higher than in 2001, 202 percent higher than when NAFTA took effect, and 396 percent higher than when the United States ran its last annual trade surplus.

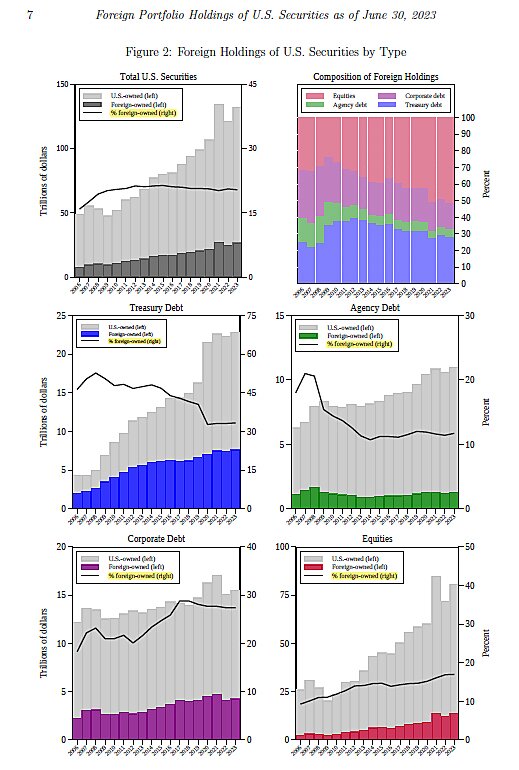

Outside of U.S. government debt purchased by foreigners (which has been declining in recent years, by the way), there’s simply no support for the idea that Americans must someday repay the foreign capital surpluses that mirror U.S. trade deficits—or that they’re a wealth-draining problem to be solved. In fact, even though the total value of U.S. securities (Treasury debt, government agency debt, corporate debt, equities) held by foreigners has increased steadily over the last two decades, its share of total U.S. securities has been basically flat (at around 20 percent) since the Great Recession because the value of American-owned securities has increased too:

Bilateral Trade Balances Are Utterly Meaningless

Another huge and common mistake is using bilateral trade balances—e.g. the U.S. trade deficit with China—as indicative of economic problems or as some sort of trade policy scorecard. (One misguided soul even went so far as to suggest recently that the U.S. “trade deficit with a country may serve as a proxy for the level of imbalance in trade policies and the level of reciprocal tariff.” Yikes.)

Most basically, the world has more than two countries, so—just as my trade deficit with my grocery store tells us almost nothing about my overall financial position—a U.S. trade deficit with, say, Mexico tells us almost nothing about our own economy. The authors of that Cato essay, Andreas Freytag and Phil Levy, provide a simple example (emphasis mine):

Let us imagine that the United States sells $100 billion of wheat to Saudi Arabia. Saudi Arabia sells $100 billion of oil to China. China sells $100 billion of consumer manufactures to the United States. If this is all the trade they do, each country will have balanced trade ($100 billion in exports and $100 billion in imports). But the United States will run a $100 billion trade deficit with China. Even if you’re worried about how trade balances might affect the US economy, that US-China trade deficit tells you nothing.

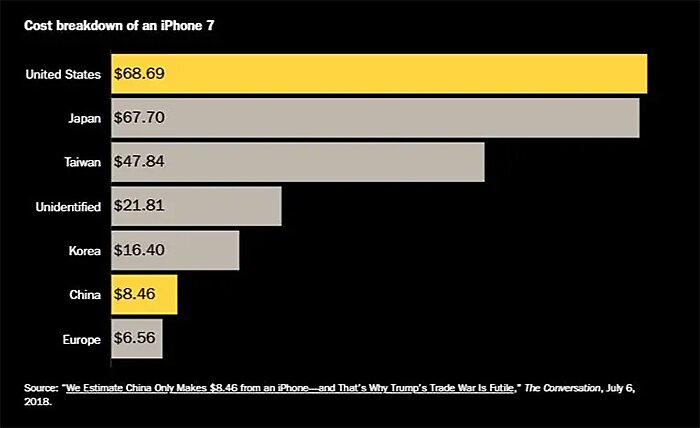

Global supply chains, in which goods assembled in and shipped from one country contain parts from many others, compound the complexity—and the meaninglessness of bilateral trade balances. Traditional trade stats are reported on a “gross” basis, meaning the full cost of, say, a car imported from Mexico is attributed to that country, even though it contains parts and materials made in other countries (including the United States). Here’s a classic example of an iPhone 7, the entire cost of which our trade stats attribute to China, even though most of the phone’s actual content was produced elsewhere:

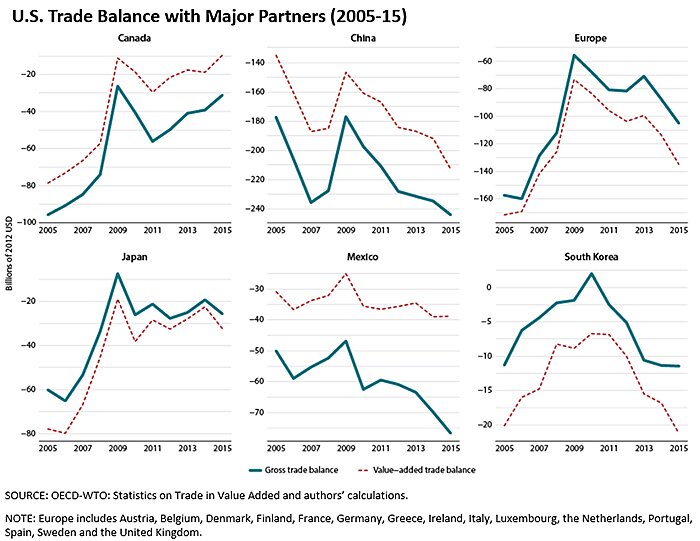

Given the proliferation of global supply chains in recent decades, trade economists understand that bilateral trade balances today don’t accurately reflect the actual amount of content produced and traded between two countries. Thus, when economists examine that content (so-called “value-added”), U.S. bilateral trade balances change significantly:

Other aspects of globalization make things even messier and further argue against using trade balances—bilateral or overall—as some sort of international economic scorecard. As we discussed in December, for example:

American investment abroad … confounds simplistic trade deficit moaning. As recent research has noted, in fact, if you included U.S. multinationals’ non‑U.S. sales of goods made overseas and their U.S.-origin services and intellectual property embedded in those products, the U.S. trade balance would shrink substantially.

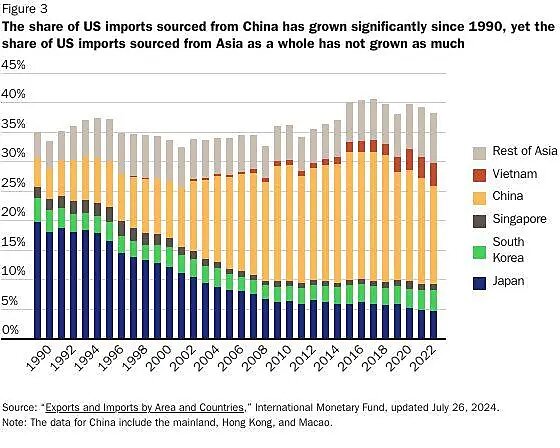

These issues also help to explain why tariffs and other measures meant to reduce bilateral trade balances—as former U.S. Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer recently proposed—won’t be very effective. And Lighthizer should know: As shown above, the China tariffs imposed when he was USTR narrowed the U.S.-China trade balance but expanded our trade deficits with countries like Vietnam, which were exporting goods to the United States that—given Asian Pacific supply chains—likely contained lots of Chinese content. You can actually see this happen in the chart below, too—as China’s share of U.S. imports from Asia expanded significantly since 1990 and then started shrinking when the tariffs hit and other Asian countries took its place:

And because the underlying macroeconomic forces driving the overall U.S. trade deficit didn’t change when the tariffs were imposed, neither did the deficit.

Summing It All Up

So, trade deficits don’t hurt jobs or growth, aren’t trade or economic scoreboards (especially bilateral ones), and can’t be fixed by things like tariffs or subsidies. They’re not a drag on growth, and they don’t represent lost American wealth or a debt we must repay. Trade balances can tell us stuff about an economy—but much less about a nation’s trade policy and much more about its citizens spending and saving, as well as the economic and noneconomic forces affecting those millions of individual decisions. In the United States, much of the stuff our trade deficit reflects isn’t a problem and, in the case of our attractiveness as a global investment destination or the U.S. dollar’s importance in international commerce, is decidedly a good thing. And outside of a recession or the world ditching the dollar, government efforts to shrink the trade deficit will fail unless they fundamentally change Americans’ savings and investment decisions or unless Washington finally gets its fiscal house in order. Indeed, if policymakers and wonks—despite all the above—still feel compelled to reduce the U.S. trade deficit, eliminating our bloated federal deficits would be the most straightforward and benign way to do it.

Funny how none of the trade deficit worriers ever mention that.