One of the big themes of my forthcoming book, Empowering the New American Worker, is that our political class often misunderstands—willfully or otherwise—much of the U.S. workforce. I discussed this problem generally back in September, but there may be no better specific example than the Biden administration’s recent broadside against independent work, in the form of a new Department of Labor proposed rule for determining when a worker is properly classified as a contractor or an “employee” under the Fair Labor Standards Act (and thus subject to minimum wage, overtime, and other labor regulations). The rule is complicated and still preliminary, but most experts agree on its objective and likely result: to make it more difficult for workers to be classified as independent and thus to force many of them to be reclassified as employees, whether they like it or not.

Such a rule makes sense if you think, as many in Washington seem to do, that independent work in the United States is primarily about a handful of poor gig workers forced to toil as contractors by a nefarious employer abusing his market power to save a few bucks on taxes/benefits and to avoid various labor protections. Thus, the theory goes, state and federal governments must step in to ensure that almost every worker is classified as an employee so they can rightly enjoy the fruits of a highly regulated U.S. labor market. (More on those supposed fruits another time.)

As Ilana Blumsack and I detail in Empowering, however, the reality of independent work in the United States is far different from what proponents of the Biden rule would have you believe. And implementing that rule—or others like it—could harm millions of American workers, and the U.S. economy more broadly, for no good policy reason.

The Reality of Independent Work

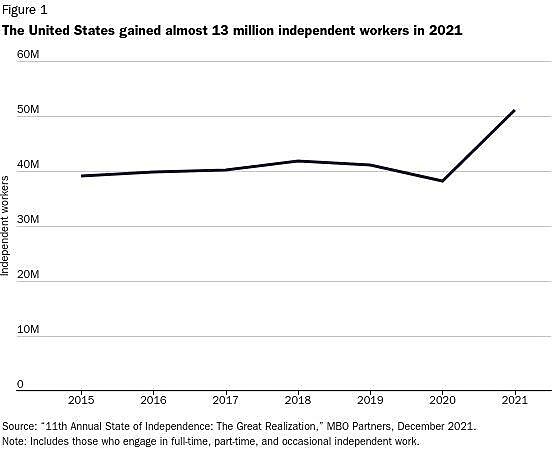

For starters, independent work isn’t some fringe part of the American workforce: In 2021, for example, independent contractor support firm MBO Partners estimated that more than 51 million Americans worked independently at some point during the year, up from 38 million in 2020. Freelance platform Upwork, meanwhile, found that 36 percent of American workers dabbled in freelancing in 2021 and had previously projected that freelancers would constitute a majority of the U.S. workforce by 2027.

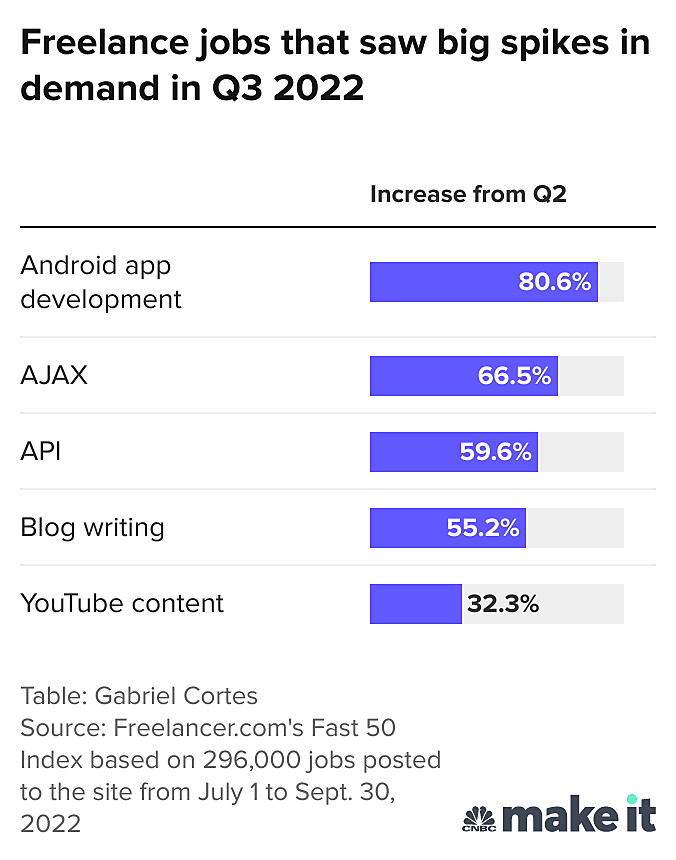

Second, independent work doesn’t primarily consist of oft-maligned “gig work” (e.g., rideshare drivers or DoorDash deliverers). Instead, most freelancers engage in “white-collar” work outside the gig economy, with the most common roles in skilled industries such as marketing and computer programming. In 2019, in fact, the IRS found that only 8.6 percent of independent workers worked in the gig economy, and this year’s fastest growing freelance occupations are in app and web (“AJAX” and “API”) development, along with blog writing and YouTube content creation.

Third, and again contrary to the narrative, most Americans engage in independent work because they prefer the arrangement over traditional employment—not because they’re forced into it by some greedy business owner. A big driver of this preference is the flexibility and control—over schedule, location, clients, public affiliations, etc.—that a standard employee usually lacks. A 2019 survey, for example, revealed that 70 percent of independent workers cite flexibility as a major reason for engaging in independent work. Economists also recently found that nearly half (46 percent) of independent workers choose to freelance because they can’t work a traditional 9‑to‑5 job, often because of either medical issues or family commitments.

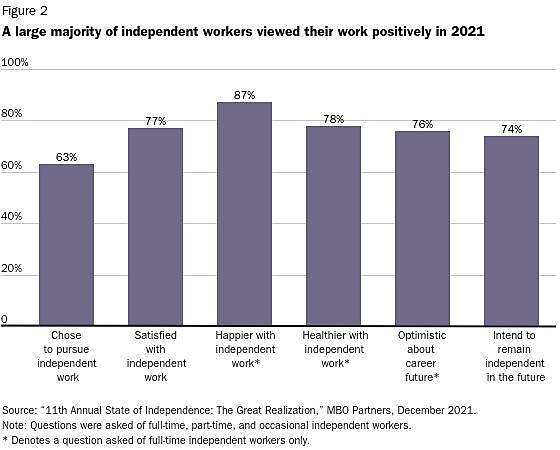

Given these and other factors, MBO Partners has found that almost 80 percent of all independent workers report being satisfied with their arrangements, nearly 90 percent of full-time independent workers said they were happier in independent work than in traditional employment, and almost three-quarters of all independent workers want to remain in independent work going forward.

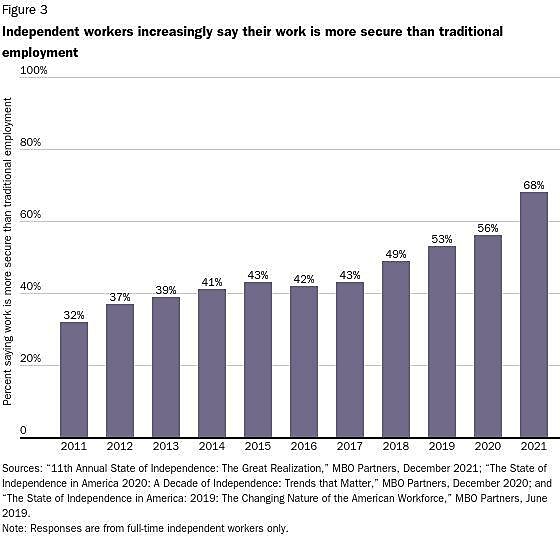

That same survey also found, perhaps surprisingly, that almost 70 percent of full-time independent workers in 2021 believed that their work is actually more secure than traditional employment:

Thus, only 11 percent of survey respondents said they’d return to traditional employment if given the opportunity.

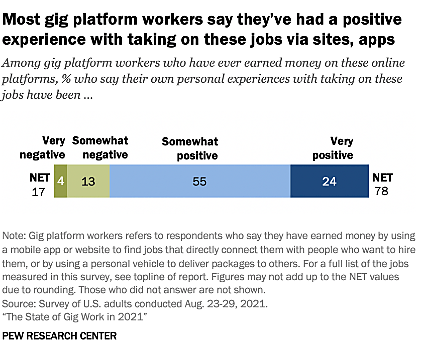

These preferences extend to gig work. According to a 2021 Pew survey, for example, almost 80 percent of gig platform workers rated their experiences positively:

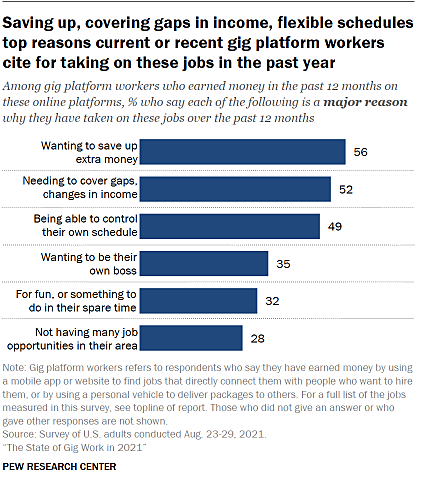

Again, flexibility is key here. Almost half of Pew’s respondents cited schedule flexibility as a major reason for engaging in gig work. A separate 2019 examination of more than 1 million U.S. Uber drivers found that drivers valued the work’s flexibility—in both the timing and amount of work—at $150/week (or 40 percent of expected earnings). The researchers also found that drivers would need a 50 percent raise to work as an employee for a less flexible, more controlling taxicab company.

Pew also found that only 28 percent of surveyed gig workers last year said they performed the work because there were few other job opportunities available where they live—thus undermining the theory that gig workers have been forced into the arrangement by those dastardly, monopsonistic employers.

None of this screams “exploitation.”

Indeed, buried in these data is the fourth key fact about independent work that’s usually ignored by those who demonize it (but evident to anyone who’s chatted with a few Uber drivers): Many independent workers don’t work full-time in the field at issue and instead treat the arrangement as a “side hustle,” to pay for school, or to cover bills while they pursue their passions. A 2021 survey, in fact, found that 80 percent of gig-working respondents in Michigan, Ohio, and Pennsylvania were part-time, and a separate 2021 report found that two-thirds of independent workers nationwide reported being either “part-time” or “occasional.” (Disclaimer: I’ve been one of these side-hustlers for about a decade now; I most definitely prefer it that way.)

Fifth, for those who do depend on independent work for most of their income, the money can be quite good. According to MBO Partners, 58 percent of full-time independent workers report making more money through freelance or gig work than if they had been engaged in traditional employment. A recent Wall Street Journal piece profiled the pandemic-era rise of six-figure earners in independent work:

High-end gig work in consulting, marketing, writing and project management has gained more traction during the pandemic, independent consultants and recruiters for such project-based work say.

Once viewed as an off-ramp for executives drifting toward retirement or a life-raft for those struggling to re-enter the workforce after a break, independent consulting has emerged as a viable, and even attractive, option in today’s hot job market. Many professionals see the perks: more money, flexible hours and control over the type and amount of work performed. Companies can tap a significantly broader talent pool to work remotely as they struggle to hire all the full-time staff they need.

This mutually-beneficial work arrangement, in which both employers and workers win, is a far cry from the adversarial, zero-sum situation that critical Washington politicians so often portray.

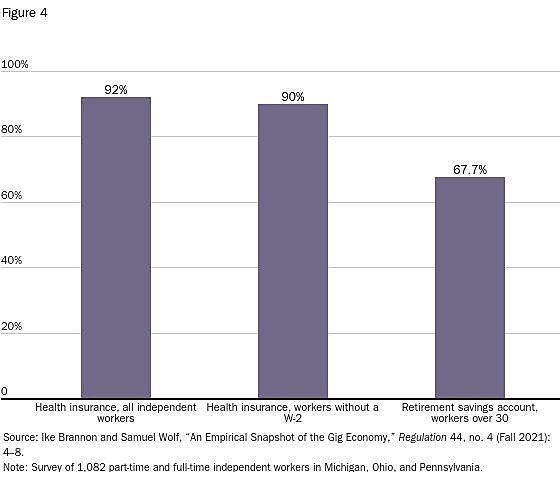

Sixth, it’s a myth that most independent workers lack access to traditional employee benefits such as health insurance or a retirement account. One recent survey, in fact, found that independent workers had health, retirement, and other benefits—through a spouse or individual markets—at levels similar to traditional employees.

Finally, it’s important to note that independent work has other, rarely-mentioned economic benefits. One recent study, for example, found that an increase in ridesharing services in a particular area leads to an average of 5 percent increase in new business formations (even higher in economically depressed areas). Independent workers have also been found to be an essential part of many cash-constrained tech startups that have one-off projects or can’t afford to hire specialized talent full-time given the ventures’ early (and risky) stage of development. And Upwork found that much of the pandemic-era surge in business formations has been from freelancers. Independent work has also helped reduce unemployment and provide a bridge for workers in between jobs: According to one recent study, a 1 percent increase in a county’s unemployment rate led to a 21 percent increase in gig economy employment in the county.

Consumers also gain from independent work, beyond simply the benefits arising from new competition (more and more innovative choices, lower prices, etc.). For example, ridesharing services have reduced drunk driving, as more people choose to Uber home rather than drive. Food delivery services helped restaurants weather pandemic lockdowns (and feed hungry customers). And new platforms such as Bite Ninja have helped restaurants navigate labor shortages by having gig workers run drive-thru windows from home.

What a world.

None of this is to say that all independent work is great, or that everyone should be an independent worker. Instead, the arrangement—like everything—is about tradeoffs: Independent workers have more flexibility and control over their professional and personal lives than do traditional employees, but they usually “pay” for those advantages by forgoing job stability, certain regulatory protections, and some employer-provided (often mandated) benefits. Millions of workers, including me, willingly accept this tradeoff, and many can make a good living doing so. Millions of others prefer to be an “employee.” And the market sorts us accordingly.

Given these realities and the broader economic benefits, there’s simply no compelling policy reason for the state being involved here at all, much less actively discouraging independent work from Washington, D.C.

The Proposed Biden Rule

The Biden administration apparently disagrees. Their new proposal would significantly expand the situations in which a worker must be treated as an employee by applying an opaque, watered-down version of the “ABC Test” that several states have adopted to crack down on independent work. Under that test, a worker may be classified as independent only if he meets all three of the following criteria: A) he’s free from the control of the entity for which the work is performed; B) he performs work that is different from the hiring entity’s usual business; and C) he already works in the same trade, occupation, or business as the work being performed for the hiring entity. California adopted the ABC test in 2019 with the passage of the controversial Assembly Bill 5 (AB 5), and five other states (Connecticut, Massachusetts, New Jersey, Nebraska, and Vermont) also use it.

As these states’ experience shows, applying the ABC test nationally would force hundreds of now-independent occupations to be reclassified as employees, whether workers and employers like it or not. Thus, for example, a freelance writer who contracts to write articles for online magazines would be considered an employee because his work is in line with the publications’ usual business. A freelance fashion photographer would also be an employee because she has to work at certain times (e.g. during a runway show) and thus isn’t free from the hiring entity’s control.

Congressional Democrats’ “PRO Act,” which the House passed last year, would have embedded the ABC test into federal law—a longtime Democrat and labor union priority. But since the legislation stalled in the Senate (and there’s an election next week), the Department of Labor’s proposed rule seeks to do as much ABC’ing as possible via a regulatory re-interpretation of FLSA. The rule doesn’t explicitly include the ABC test (probably because, legally speaking, it can’t), but as Erik Sherman recently showed in Forbes, it’s obviously pushing that way. For example—

- The proposed rule would expand the current definition of “control exerted by the employer” to include “detailed discussions of … scheduling, supervision, price-setting, and the ability to work for others,” while “not limiting control to control that is actually exerted.” This is essentially the “A” prong of the ABC test, broadening the definition of “control” to reclassify as many workers as possible as employees.

- The rule would consider “whether the work is integral to the employer’s business rather than whether it is exclusively part of an ‘integrated unit of production.’” This change would consider work that is separate from a company’s main functions but is still a core part of the organization’s purpose as the work of an employee, not an independent worker. Think of a freelance writer at a magazine. This is essentially the “B” prong of the ABC test.

As Sherman and others note, the rule also is vague and open to interpretation, meaning more Labor Department enforcement actions and more economic uncertainty (which itself would discourage independent work). Regardless, most everyone agrees that the rule’s practical result would be that many American workers—including ones who want to be independent contractors—will be reclassified as employees.

Just how many workers isn’t exactly clear, but it’s probably a lot. Economists Robert Shapiro and Luke Stuttgen estimate that a nationwide ABC test would’ve reclassified more than 4 million workers as employees, but that estimate is probably low because they assumed there were only 17 million independent workers in the country. As already noted, MBO Partners calculated 51 million independent workers in 2021—three times the Shapiro/Stuttgen number. So a back-of-napkin estimate shows that as many as 13 million workers could be reclassified as employees under a nationwide ABC rule.

The Labor Department rule doesn’t go full ABC, but it’s certainly moving that way—and affecting millions of workers in the process.

Documenting the Harms of Restrictions on Independent Work

Unfortunately, recent analysis shows that this forced reclassification could have significant economic harms—including for the very workers the proposed rule is supposedly protecting. Much of this stems from the fact that traditional employees are more than 20 percent more expensive for companies to employ than independent workers, thanks in part to FLSA. Compliance and mandated benefits, such as health insurance, drive up costs, especially for smaller firms. Thus, firms that are unable or unwilling to pay more to rehire previously independent workers could respond by raising prices or cutting the positions entirely.

We’ve seen this play out in California. In 2020, for example, Uber estimated that AB 5 would increase costs by $3,625 per driver in California, could double the price of rides, and would reduce rideshare availability by up to 60 percent. Right after AB 5 passed, Vox terminated more than 200 freelance writers, and many other freelancers were canned around the same time. Thus, California scrambled to exempt more than 100 occupations from AB 5 since 2019, including rideshare drivers, writers, and photographers. As we’ve discussed, however, many other occupations haven’t been spared —including about 70,000 “owner-operator” truck drivers who have been prohibited since July from continuing to work independently. (Experts have recently suggested that—instead of just caving and becoming (unionized) employees—many truckers have started their own companies to remain independent.) My Cato colleague Walter Olson recently documented other victims: “Workers hurt by AB 5 included many tutors, performers in music and theater, plumbers, nurse practitioners, writers, photographers, contract software developers, and many others.”

And California isn’t the only state dealing with ABC blowback. In New Jersey, for example, newspapers are livid over a new regulation classifying deliverers as employees, a change that could annually cost already struggling news companies $3 million each. In Massachusetts, the attorney general has been attempting to reclassify rideshare drivers as employees, despite 83 percent of drivers preferring to remain independent workers.

Some of this has also already played out nationally, as Olson explained:

We’ve … seen this at the federal level in its previous go‐round as the Obama administration’s 2015 initiative along the same lines (although this version would go even further). As we noted then, the intended restrictions on franchising and subcontracting would endanger the thriving white‐van culture of small skilled contractors by which so many tradespeople now find upward mobility, trading it instead for clock‐punching at some company division. And it would force tech, creative, and startup firms that currently outsource functions like cafeteria, janitorial, and landscape maintenance to take on much wider direct employment responsibilities they may not be particularly well equipped to handle.

Given these issues, it’s no surprise that Shapiro and Stuttgen estimated that a nationwide ABC test could lead to the termination of 3.8 million independent work positions—a number that, again, could be much higher given the prevalence of independent work today.

And for what?

Summing It All Up

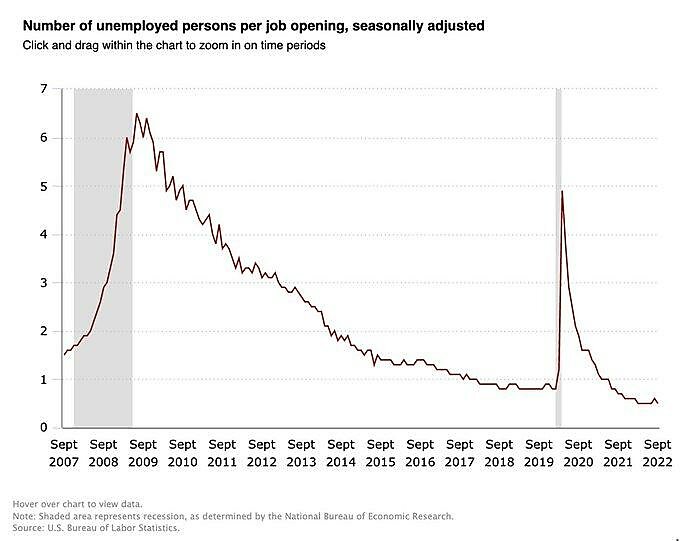

Tens of millions of Americans engage in independent work—either full-time or as a side hustle—and the vast majority of them (us) do so voluntarily because they (we) prefer it to traditional employment. Surely, not every independent worker is happy with his situation, nor is every U.S. business utilizing contractors on the up and up. But the vast majority of them are, and the Department of Labor rule does nothing to distinguish those millions from the problematic few. As such, the rule would needlessly inject the federal government into the voluntary contractual decisions of millions of workers and companies, denying many of them a mutually beneficial arrangement to which both parties willingly agreed. That’d be a particularly galling and out-of-touch result, given that the U.S. labor market remains (per data released just yesterday) piping hot:

As Blumsack and I explain in Empowering the New American Worker, there are some important reforms—particularly related to taxes, benefits, savings, and licensing—that federal and state governments should implement to improve the independent work situation in the United States. But, unlike the Labor Department’s proposed rule, these changes would make it easier, not harder, for workers to engage in independent work. Contrary to the stereotypes, that change would be good for millions of independent workers and perhaps millions of other Americans contemplating a shift out of traditional employment. But it’d obviously be bad for the thousands of politicians and union leaders who see political value in restricting independent work via AB 5‑style legislation.

And this time of year, I think we all know who wins that contest.