Dear Capitolisters,

Here’s hoping you had a great Independence Day. Due to the holiday and some forthcoming business travel (yet again!), I’m going to revisit an issue—supply chain stress—that we’ve hit a few times in the past but not recently. So today I’m going to ditch my typically sunny optimism and look at three potential dark clouds on the horizon for U.S. supply chains, and thus the U.S. economy. The most frustrating part? They were all avoidable.

Supply Chain Chaos Is Cooling (a Little)

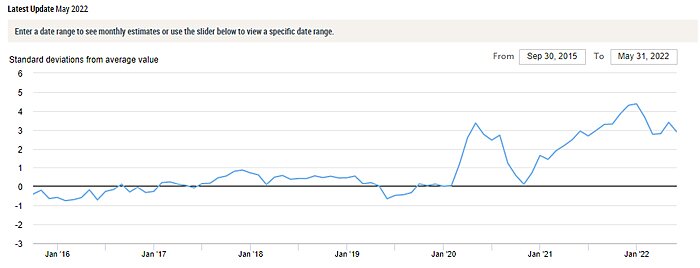

Throughout June, we were treated to good news on the supply chain front, with various indicators showing declines from last year’s all-time peaks of supply chain stress and even some improvement since the Russian invasion began. For example, here’s the New York Fed’s global supply chain pressure index through May (the June update will come later this week):

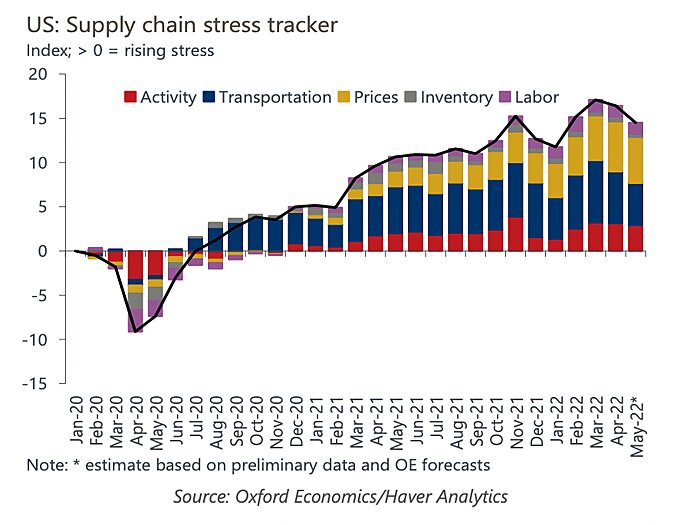

The GSCPI is a global index, but U.S. indices—such as Oxford Economics’ supply chain stress tracker—showed similar movements:

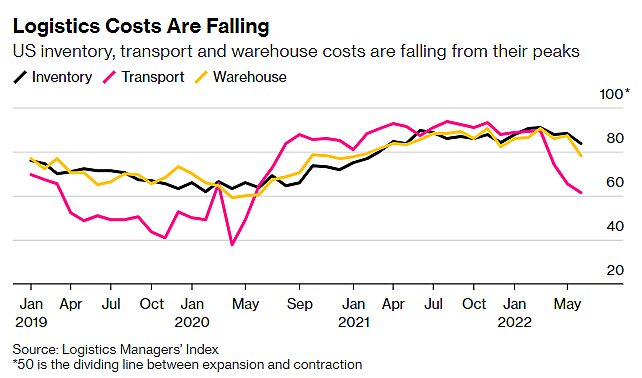

Other U.S. indicators looked even better last month. According to Bloomberg, for example, a key “gauge of supply-chain pressure in the U.S. economy”—the Logistics Managers Index—just had its third straight decline in June and fell to its lowest level since mid-2020 and below its all-time average of 65.3.

Around the same time, the closely-watched Philadelphia Fed Manufacturing Business Outlook survey showed that metrics like orders, delivery times, and prices were not only improving but in some cases nearing pre-pandemic levels:

Supply chain crisis? What supply chain crisis? pic.twitter.com/nhxgLaOPJT

— Ian Shepherdson (@IanShepherdson) June 16, 2022

Supply chain stress easing? Outlooks for prices paid and delivery times edged lower in June @philadelphiafed … latter is coming down closer to its lowest since pandemic started pic.twitter.com/ExEWnbZEMk

— Liz Ann Sonders (@LizAnnSonders) June 17, 2022

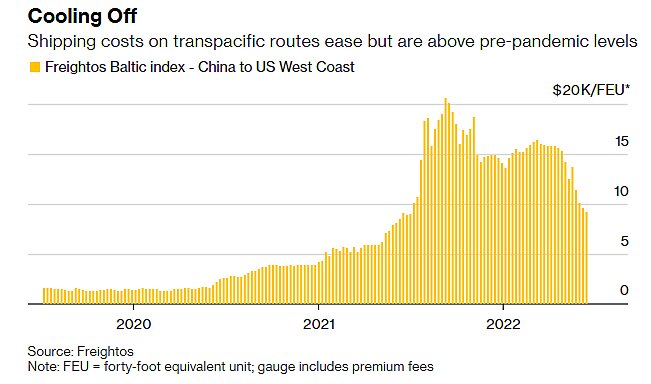

Transpacific shipping rates are also coming down:

To be clear: Things aren’t perfect out there right now. Most obviously, even the positive indicators I’ve cited above aren’t all back to, say, 2019 levels. And other things, such as port backlogs, remain a concern (in Europe too). Nevertheless, recent supply chain trends for both the U.S. and the world seem to be heading towards pre-pandemic normalcy—reflecting both discrete, near-term changes (e.g., Chinese lockdowns easing) and broader, more systemic factors (e.g., central bank tightening, a slowing U.S. economy, global supply chains adapting, and U.S. consumers shifting their spending back to services after a year-plus of bingeing on goods).

But for How Long?

Those systemic factors argue for continued U.S. supply chain improvement in the months ahead—assuming, of course, that new problems don’t emerge in the meantime. Three recent events, however, make that a risky assumption.

First, labor contract negotiations at all West Coast ports—including and especially the crucial Los Angeles/Long Beach gateway that handles a huge amount of total U.S. import/export traffic—have predictably flared up. The Washington Post’s Catherine Rampell explained earlier this week the status of these talks and their implications:

The labor contract for 29 West Coast ports, which covers 22,000 dockworkers, lapsed over the weekend. For now, talks continue. But if a major work stoppage or slowdown results, it could wreak havoc on the country’s already-fragile supply chains, with potentially catastrophic consequences for inflation and the economy.

Also, of course, for Democrats’ chances in the midterms.

This isn’t some remote risk. The last time this contract was being renegotiated, starting in 2014, talks broke down and work slowdowns led to expensive shipping delays. The Obama administration had to intervene. Labor disruptions (strikes, lockouts, slowdowns) also occurred during West Coast port contract negotiations in 2002, 2008 and 2012.

Today, the stakes are even greater, with inflation at 40-year highs. Both sides in the negotiations presumably know additional port disruptions could be disastrous — a reality that strengthens labor’s hand. Truckers, retailers, farmers and others reliant on these ports for their livelihoods are already deeply worried about the prospect of more logjams.

As you’ll recall from my September 2021 deep dive on America’s ports problems, West Coast labor contract disputes can lead to the “occasional, economy-crippling port stoppages (and other non-economic harms)” that Rampell also notes because the International Longshore and Warehouse Union (ILWU) “controls essentially all longshore labor for all West Coast ports.” That not only gives the union immense leverage in labor talks but also ensures that a work slowdown in, say, Seattle just so happens to coincide with one in Oakland, exacerbating the overall supply chain fallout. Just as I predicted last year, the key issue in the current talks is automation: the ports, which are some of the least efficient in the world, want to automate more of their operations to increase port efficiency (and they have a brand new study and both recent international and domestic experience backing them up), but the ILWU wants none of it because they fear automation will cause widespread job losses. (A fear that appears to be misplaced.) The union went so far last week as to propose that California assess a tax—ahem, a “displaced worker impact fee”—on “any new automation projects at the LA-LB port complex to offset the public costs resulting from dockworker job losses caused by automation.” (Now, class, what happens when we tax something? Exactly.)

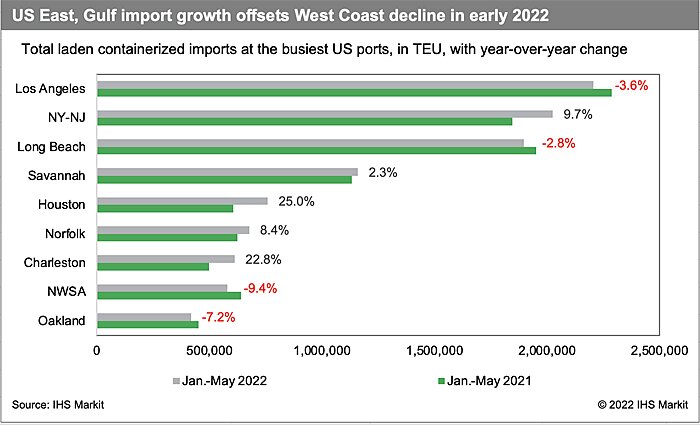

Some or most of this could be posturing, but—as Rampell notes—U.S. importers and shippers are worried, and many are searching for alternatives to the West Coast (fueling backlogs out East!). But, given the sheer magnitude of trade volumes and related infrastructure at issue, as well the sheer time needed to get to ports like Houston, New York/New Jersey, or Savannah, there’s only so much that U.S. companies can do in advance to mitigate the damage caused by a potential work stoppage or even slowdown out West. Some trade associations have called for President Biden to intervene personally to get a deal done, but it’s not exactly clear that he’s willing to do that (similar situations indicate not) or that there’s really much he can do here. So… stay tuned.

Second, and staying on the West Coast, news arrived late last week that the U.S. Supreme Court refused to hear a challenge to California’s Assembly Bill 5 (“AB 5”), which expands the definition of “employee” to encompass many independent workers (and thus to subject them to various state labor regulations), including some 70,000-plus “owner-operator” truckers in the state. Those truckers had been spared from AB 5 pending the outcome of the last-ditch SCOTUS appeal; now that the appeal is kaput, it’s expected that the truckers’ exemption will be dissolved immediately. At that point, the longstanding business model that many California (and U.S.) trucking companies utilize will be effectively illegal in the state. Companies and truckers will eventually adjust, but it’s not clear how long that will take, and the near-term impact could be severe:

“Gasoline has been poured on the fire that is our ongoing supply-chain crisis,” the California Trucking Association said in a statement following the Supreme Court’s decision to deny a judicial review of a decision of a lower court, a process known as certiorari.

“In addition to the direct impact on California’s 70,000 owner-operators who have seven days to cease long-standing independent businesses, the impact of taking tens of thousands of truck drivers off the road will have devastating repercussions on an already fragile supply chain, increasing costs and worsening runaway inflation,” the CTA said….

California’s transportation industry is already taking action to see how business models will fit the new paradigm, Harbor Trucking Association Chief Executive Officer Matt Schrap said.

“This will have a profound effect on driver supply, at least here in the interim,” he said in an interview on Bloomberg Television Friday, adding that many entrepreneurs use the contract model as pathway for opportunities in trucking. “We’ve got many companies who have been planning for this, but we’ll see how the chips fall.”

There may also be longer-term effects for California and the U.S. supply chains that run through the state. In particular, there’s the open question of whether AB 5 will simply push some California truckers and smaller trucking companies to other states or out of the business entirely—something that reportedly was happening even when truckers were exempt from the law. (Many truckers reportedly prefer the owner-operator model.) If AB 5’s implementation causes or accelerates longer term reductions in California trucking supply, U.S. supply chain bottlenecks could deteriorate—especially given the state’s continued importance to the overall system.

No wonder shippers are trying to avoid California!

Finally, there may also be labor-related trouble brewing for U.S. freight rail lines, with similar supply chain implications. As the Washington Examiner reported in late June:

The National Mediation Board issued a news release on June 17 announcing that “pursuant to the Railway Labor Act, the National Carriers’ Conference Committee (NCCC) and the twelve unions noted below were released by the NMB from statutory Mediation.”

This announcement meant that a mandated “30-day cooling-off period begins on June 18, 2022,” and further that “absent agreements or the establishment of a Presidential Emergency Board (PEB), the parties could exercise Self-Help as of 12:01 a.m. EDT, July 18, 2022.”

“Self-help” here could turn out to be another word for “strike” after a few more hurdles are cleared.

Some have questioned the NMB’s actions here, but the more important issue (for today’s purposes, at least) is that a possible strike by labor or lockout by management, while not imminent, wouldn’t be that far off—even if Biden appoints a PEB, as is expected. The same Examiner piece walks through the timeline and potential implications:

If we do the math, 30 days from June 18 is July 18, 30 days from July 18 is Aug. 17, and 30 days from Aug. 17 is Sept. 16. That’s the approximate expected first day that several unions could call a massive strike that could cripple supply chains with an election less than two months away.

The process leading up to a legal rail strike is intentionally drawn out because labor law on railroads is designed to encourage settlement and discourage strikes, given what a strike could do to the broader economy. Supply chains are straining to get goods to shelves. A rail strike could break them.

Just like the port talks, there are massive political and economic incentives for all parties—but especially Biden and congressional Democrats—to reach a freight rail deal and avoid a strike/lockout. But, as the Examiner and others have noted, “there are many sticking points between the unions and the railroads, including wages, benefits, and especially automation.” (Automation again! Ugh.) Will these hurdles be surmountable in a mere 90 days? If not, Congress might also have to get involved because “freight railroads are deemed so essential to the economy and national defense”—injecting even more uncertainty into the process, especially since it’s right before a midterm election.

It’s a huge mess, and even if there isn’t a strike/lockout, none of this uncertainty is good for U.S. companies’ supply chain plans (which surely extend beyond a mere 90 days). No surprise, then, that firms dependent on freight rail just wrote to Biden expressing their grave concerns about a possible work stoppage and urging the administration to move quickly to prevent one.

Summing It All Up

Unknown problems—new international conflicts, new COVID variants or policies, natural disasters, and the like—could imperil this Spring’s (relative) supply chain calm. But it seems to me that we should be far more concerned these days about the known problems: in particular, troubled labor negotiations affecting U.S. port and national freight rail systems and the application of California labor law to commercial trucking’s longstanding “owner-operator” model. At best, these issues will add uncertainty to U.S. supply chains; at worst, they could reverse months of improvement—precisely what the limping U.S. economy doesn’t need right now. Maybe major problems can all be avoided, but doing so will require White House actions in the labor negotiations that could, as Rampell cautions, put President Biden in the uncomfortable and unfamiliar position of siding against his union allies (lest his decisions cause further economic problems). It’ll also require an urgency and decisiveness that the White House has rarely displayed—as even the president’s allies acknowledge.

Will they come through when it really counts? Stay tuned.

Chart of the Week

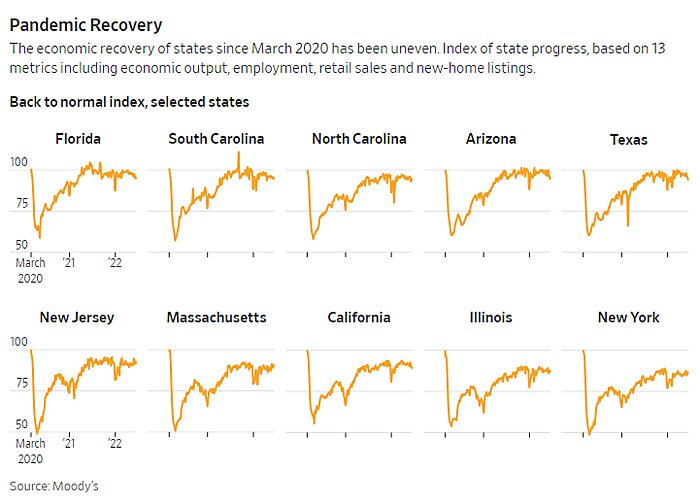

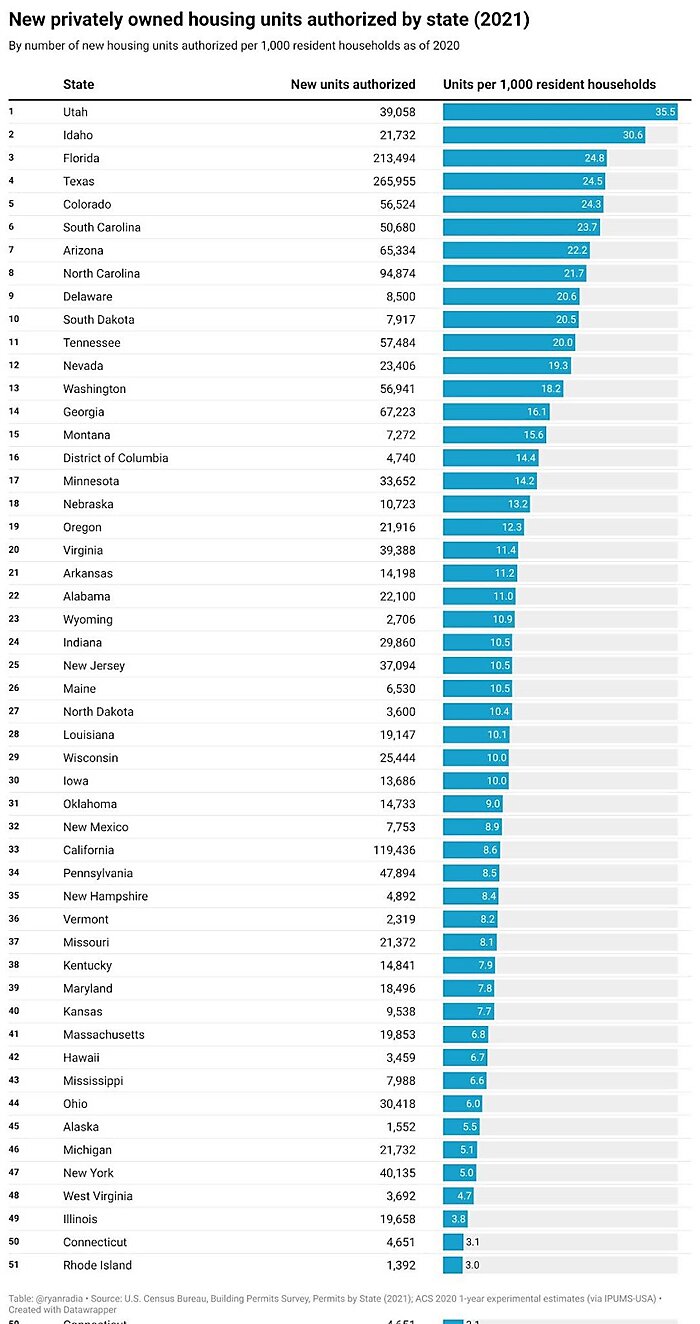

Remote work, cost of living driving a red state migration boom

The Links

Independence Day’s immense positive externalities

Infant formula, vaccines, and the perils of top-down economic nationalism

“24 charts that show we’re (mostly) living better than our parents”

So much for that infinite semiconductor demand (more)

U.S. tariffs on non-China imports boost China imports

Private markets/capital (and demand), not government, drive green energy expansion

“What Caused the Murder Spike?”

Regulations, not SCOTUS, are the real barrier to clean energy technologies

Biden to lift some China tariffs? (more)

The FDA regulates sunscreen like a drug, with predictable results