Dear Capitolisters,

Last week the world was gripped by a very large ship blocking the Suez Canal—one of the global economy’s most important commercial waterways. The culprit, the Ever Given, was finally freed on Monday after days of digging and tugging, but not before we were treated to plenty of (good) jokes about the situation and (bad) takes about its broader meaning for trade and “globalization.” The New York Times, for example, told us that the “Stuck Ship Is a Warning About Excessive Globalization” (the paper was not alone), while at least one nationalist pundit openly hoped that the ship would stay stuck as a “monument” to outsourcing, multinational corporate greed, and other trade-related evils.

As is often the case, these piping hot takes were pretty misguided: While certain companies, ships, and consumers undoubtedly took a financial hit and while the mess contributed to ongoing supply chain tensions, the overall damage is relatively small and the Ever Given will be forgotten soon enough. Sometimes a stuck ship is just a stuck ship, until it becomes an unstuck ship, at which time things go back to relative normalcy and we find other things to goof on while waiting for dinner.

For us at Capitolism, however, the Ever Given isn’t just a stuck/unstuck ship. It’s an opportunity to learn a little about the nuts and bolts of global trade and in the process debunk something I briefly noted a few weeks ago: the populist caricature of “globalization” as “a new phenomenon created by corporatist (probably libertarian) elites” through “trade deals” and other forms of supposed “free market fundamentalism.” Instead, we’ll see what “globalization” actually is: the daily work of millions of individuals to conceive, produce, ship, and consume goods and services around the world. It’s work that’s been going on for eons but has become remarkably easier in the last century because of things like the Suez Canal and, yes, even the formerly sideways Ever Given.

So today we’ll look into those things, which deserve as much (if not more) credit for modern globalization than any tariff cut or trade deal, and draw some broader lessons about what “globalization” really is and those oh-so-trendy populist promises to stop it.

The Ships

As I noted last time, evidence from the Bronze Age to the vikings shows that people engaged in global commerce long before things like trade agreements or even modern nation states existed. This early “globalization,” however, was hard. Really, really hard. Only in the last 150 years or so did trade accelerate because of radical improvements in technology, chief among them in shipping, that dramatically lowered the cost of moving stuff around the world.

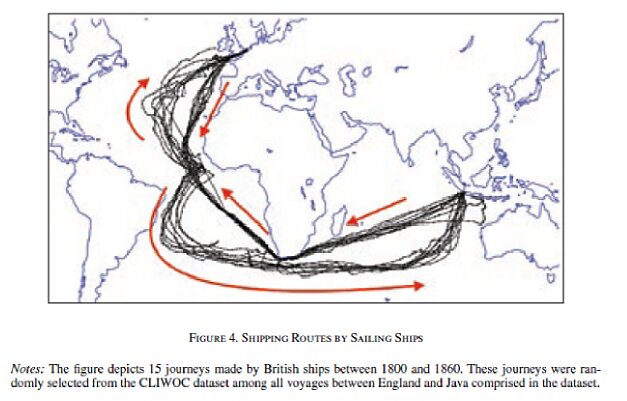

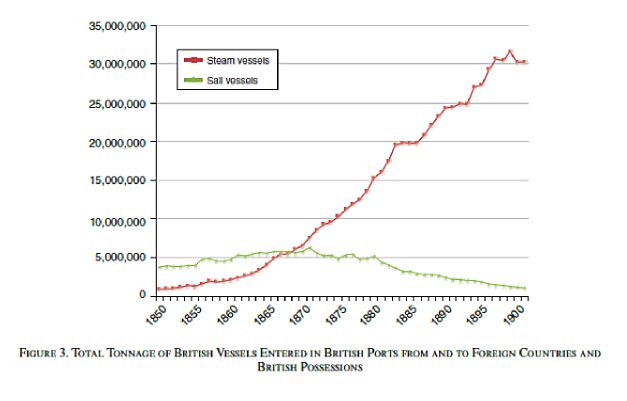

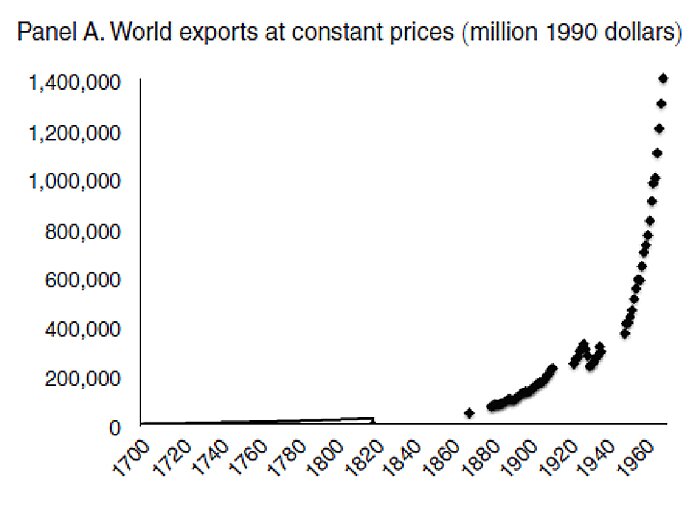

Research shows, for example, that as much as half of the first large increase in global trade—between 1870 and 1913 (aka “Globalization 1.0”)—was driven by the adoption of the steamship, which freed cargo vessels from being at the mercy of trade winds and thus shrunk shipping times (and therefore costs).

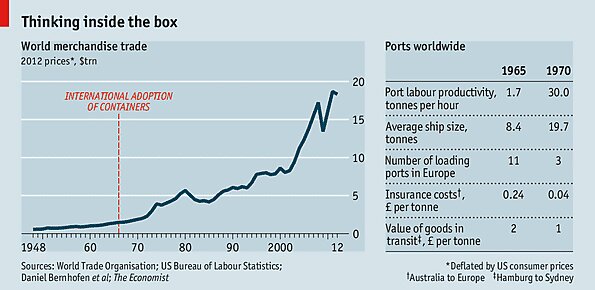

As the last chart shows, however, globalization was—after a major war-induced pause—just getting warmed up. In particular, starting around the 1950s, worldwide trade in goods began to increase exponentially to today’s historically-high levels. Trade policy—both new trade agreements like the World Trade Organization’s predecessor, the 1947 General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade, and unilateral decisions by governments to lower tariffs and other trade barriers beyond their basic GATT/WTO commitments—was undoubtedly behind some of this gain. (Indeed, new research from the Peterson Institute for International Economics shows that this latter, rarely mentioned approach was critically important for lowering global trade barriers over the last 30-plus years.)

At the same time, however, technology has also played a major role in today’s “Globalization 2.0.” Most notably, Malcolm McLean’s invention and commercialization of the shipping container in the 1950s revolutionized global trade in goods:

Before McLean developed the standardized shipping container, nearly all the world’s cargo was transported in a diverse assortment of barrels, boxes, bags, crates and drums. A typical ship in the pre-container era contained as many as 200,000 individual pieces of cargo that were loaded onto the ship by hand. The time it took to load and unload the cargo often equaled the time that the ship needed to sail between ports. That inefficiency contributed to keeping the cost of shipping very high.…

By 1966, McLean launched his first transatlantic service and three years later, McLean had started a transpacific shipping line. As the advantages of McLean’s container system became clear, bigger ships, more sophisticated containers and larger cranes to load cargo were developed.…

In 1956, hand-loading cargo onto a ship in a U.S. port cost $5.86 per ton ($55.58 in today’s money). By 2006, shipping containers reduced that price to just 16 cents per ton ($0.21 in today’s money). HumanProgress’ Board Member Matt Ridley has noted that “the development of containerization in the 1950s made the loading and unloading of ships roughly twenty-times as fast and thereby dramatically lowered the cost of trade.”

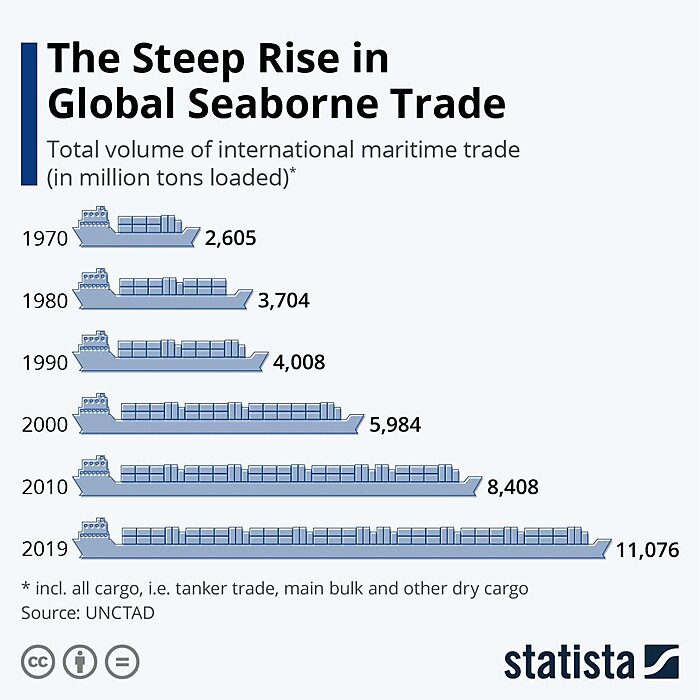

Today, increasingly massive ships like the Ever Given carry containers full of goods for a relatively tiny sum, and global trade has in turn exploded:

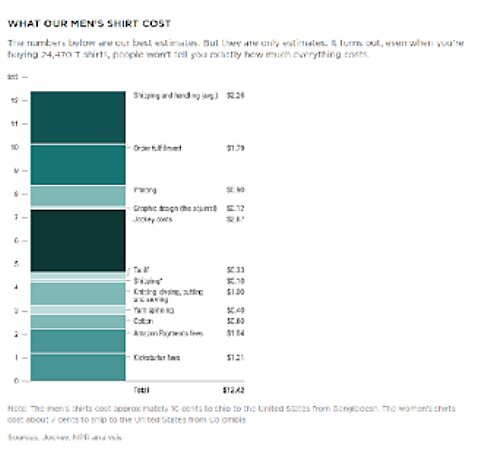

To get an idea of how this might work in the real world, consider NPR’s recent estimate that it cost the organization just 10 cents to ship a T‑shirt from Bangladesh to a U.S. port but more than $2 to deliver that shirt from the port to your home—a much shorter distance:

Because the U.S. still maintains high tariffs on cotton T‑shirts (16.5 percent) and other apparel from non-FTA countries like Bangladesh, the NPR example above also shows how modern shipping provides a huge “de facto tariff cut” for U.S. importers and consumers. In particular, if shipping costs for NPR’s T‑shirt remained at 1950s levels (i.e., many multiples of that 10-cent figure above), they’d dwarf the relatively small $0.33 tariff cost per shirt and thus act as a much larger trade barrier than the tariff itself (which is pretty high by today’s standards). Remove that practical barrier, and trade logically increases—no nefarious libertarian “elites” needed.

Economic research confirms my back-of-the-napkin example, showing the container’s enormous impact on global trade. For example, a 2016 study found that trade in 22 industrialized countries increased by as much as 1,240 percent over 15 years thanks to containerization and related transportation efficiencies—an effect on trade flows that the same researchers estimated was three times larger than the effect of free trade agreements like the GATT. Writing up an earlier version of this paper, The Economist provides this great graphic showing just how containers improved ports’ efficiency and the resulting gains in trade flows:

Another study from 2017 found smaller, but still substantial, gains for containers alone: “current trade levels could decrease by about a third if container technology did not exist. For remote trade partners, gains from containerisation would reach 78%.”

All because of a box.

Canals

Canals also play an important role in facilitating global trade, and the Suez may be the most important of them all. As Quartz explained last week—

Suez is the node in the global shipping network with the greatest effect on world trade. An estimated $400 million worth of goods flow through the canal each hour.

In a study last year, economists examined the importance of various hubs facilitating trade between various destinations. Of them, “Egypt is the most important in terms of being pivotal and being able to affect global welfare when there’s changes to how easy it is to go through this particular node,” says Woan Foong Wong, an assistant professor of economics at University of Oregon and one of the authors of the study.

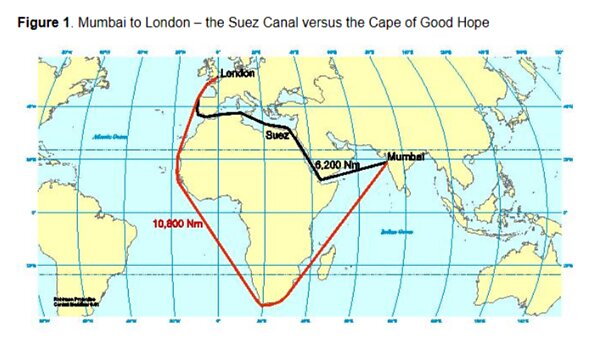

The reason is Egypt’s location. “It’s a very central hub,” Wong says. The 120-mile canal through the country connects the Indian Ocean and the Mediterranean Sea, making it a vital passage for ships seeking to travel between Asia and Europe without having to circumnavigate Africa in the process.

About 80% of the volume of international trade is transported by sea, according to the United Nations. The “very purpose of the canal is to shorten transportation routes for global supply chains,” says Yemisi Bolumole, an associate professor of supply-chain management at Michigan State University. It allows ships to save thousands of miles in their journeys, making it one of the most trafficked shipping lanes in the world. About 12% of the world’s trade volume makes its way through Suez.

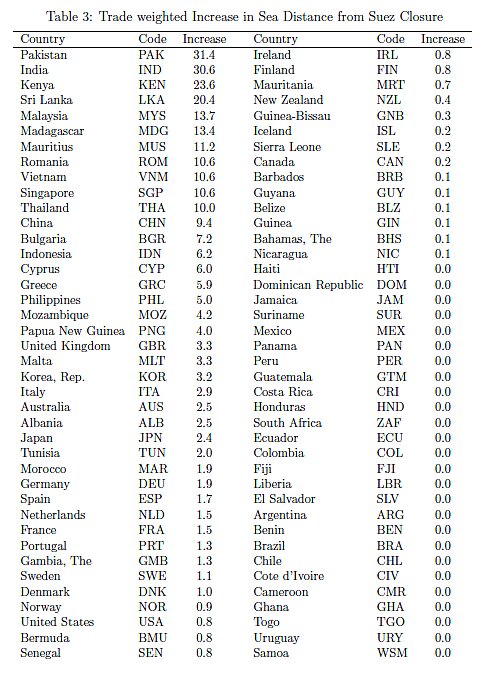

Using the Suez Canal’s 1967–1975 closure (caused by the Six Day War), economist James Feyrer quantified the canal’s impact on global trade and, by extension, countries’ economic growth. He found that, first, the canal closure dramatically increased the distance (and thus cost) of trade for certain countries—particularly those in Central Asia that trade a lot with Europe:

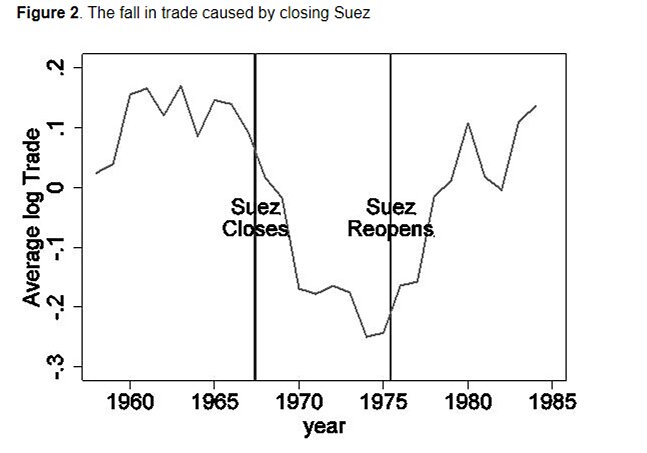

Second, the higher trade costs faced that these countries faced when the Suez Canal was closed ended up decreasing their total trade (they didn’t just reroute around Africa, for example):

And, third, the decline in total trade (and increase after the canal reopened) had a significant effect on per capita incomes in these same countries—they got poorer when it was closed and richer when it reopened. Thus, “increases in trade volumes generated by decreases in trade costs generate higher income per capita,” with the Suez Canal being a substantial “trade-cost-decreaser” (just go with it). Elsewhere, Freyer adds that his results “suggest that every dollar of increased trade raises income by about twenty-five cents” and “provide clear evidence that lowering trade barriers leads to higher trade volumes and higher incomes.” Again, he shows that the canal (and other major man-made waterways like the Panama Canal) are just like much-maligned tariff liberalization in that regard.

Summing It All Up

Canals and container ships are just two of the many incredible technologies that allow us to enjoy the benefits of the global economy every day. Research shows, for example, that telecommunications are also a critical driver of today’s globalization (and especially essential for trade in services). These hidden miracles obliterate the all-too-common populist claim that “globalization” is some sort of new and top-down phenomenon forced upon The People via backroom “trade deals” drafted by a cabal of uncaring political elites—a phenomenon that could be stopped with the flick of a policy switch (once you elect the populists to do the flicking, naturally).

In reality, much (perhaps even most) of today’s global integration has been driven by bottom-up improvements in modern technology like the Suez Canal and the shipping container—technologies that simply make it easier for us humans to do the long-distance business we’ve willfully been doing for eons. And no amount of nationalist policy-flicking will change them or the fundamental human desire to trade (though of course governments can make it easier or harder for us to do so).

This reality lends itself, I think, to two important conclusions: First, tariffs and other government barriers to trade really are, as economist Joan Robinson once observed, akin to willfully throwing rocks into our own harbors—they impose a cost on, and thus discourage, long-distance commerce just as antiquated shipping or communications technologies (or accidentally stuck ships) do. (The Ever Given mess reportedly cost billions.) The difference, of course, is that the tariffs are artificial, intentionally imposed by political actors to thwart voluntary trade, while the technological or practical “rocks” aren’t. It’s a political magic trick that the removal of the natural barriers is (mostly) cheered, while the artificial ones are often defended as if they’ve been there all along.

Second, “globalization” isn’t going anywhere, regardless of what “rocks” remain. As Dan Drezner noted in Monday’s Washington Post, “The Ever Given is not a symbol of faltering globalization—if anything, the opposite is true. It serves as a refresher course about the value that globalization still provides to the world economy.” Even if that blasted ship never got unstuck, individuals and markets would adapt—as they did during the pandemic and previous global crises—and “globalization” would messily roll on because of this value and the billions of people (aided by all sorts of cool technology) who recognize it. And that’s why claiming the Ever Given shows why we should embrace economic nationalism like claiming that your refrigerator’s breakdown shows why you should eat only canned goods. The real value is not in the refrigerator itself but what it facilitates: better food and a better life.

Stuff happens. Ships get stuck. “Globalization” will endure, regardless of the rocks in our harbors.

Chart of the Week

Necessity, invention, etc, etc. (source)

The Links

Me on semiconductor subsidies and podcasting on industrial policy

“Global supply chains are more flexible than domestic ones”

“U.S. Distillers Bitter Over 25% Tariffs Set to Double in June”

Don Schneider on the alleged decline in U.S. business investment (Part 2)

Older millennials are closing the wealth gap with their parents

The global depopulation threat

On politics and “essential” business

The Texas storms continue to disrupt supply chains

Darden Restaurants raises its minimum wage

“$15-an-Hour Minimum Wage Could Further Sting Teen Employment”

“Headed for $900 billion in unemployment benefits”

“Overregulation and California’s Childcare Crisis”

And here comes Biden’s childcare spending

The current economic optimism might actually be too pessimistic

“Homeless man becomes first person to live in 3D-printed house”