Dear Capitolisters,

Later today, I’ll have the privilege of testifying before the House Energy and Commerce Committee’s Consumer Protection and Commerce Subcommittee on “Investing in American Jobs: Legislation to Strengthen Manufacturing and Competitiveness.” This is an issue we’ve discussed (repeatedly), but it’s worth revisiting, given all that’s happened over the last year and current congressional deliberations on how to “fix” things going forward. I’m sharing a lightly edited (now with charts!) version of my opening statement below. Hope you enjoy it.

***

Chair Schakowsky, Ranking Member Bilirakis, and Members of the Subcommittee:

My name is Scott Lincicome. I’m a senior fellow in economic studies at the Cato Institute, where my research has recently focused on manufacturing, industrial policy, and global supply chains. I want to thank you, Madam Chair, for inviting me to testify today; and I want to thank ranking member Bilirakis in particular for inviting me to offer a contrasting view on American manufacturing competitiveness, supply chains, innovation, and economic resilience—one that I hope will inform your consideration of this hearing’s important topics. Importantly, I should note that the Cato Institute and its scholars do not endorse, oppose, or otherwise lobby on behalf of (or in opposition to) specific legislation. My comments are thus intended to be for educational purposes only.

Accompanying my written testimony are three recent studies that I have authored on the state of American manufacturing and its nexus with national security; on pandemic-related supply chain issues; and on the history of industrial policy, here and abroad. Summarizing this research in a few short minutes would of course be impossible, so I instead want to leave you with several core themes that carry across my work and are relevant to this subcommittee’s deliberations:

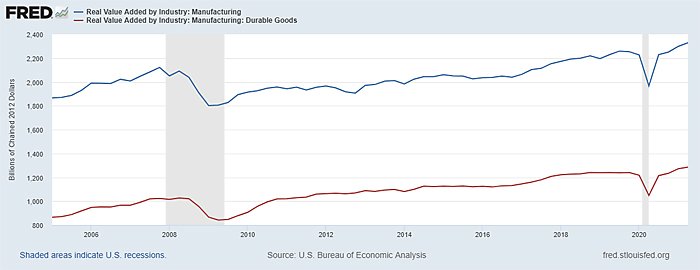

First, the United States manufacturing sector is far more competitive and resilient than is often claimed—especially in high-tech and capital-intensive industries. Data from the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) and other sources show that the U.S. manufacturing sector remains among the most productive in the world and had enjoyed, prior to the pandemic, a long stretch of gains in output, investment, and financial performance. Like all sectors, manufacturing suffered when COVID-19 first hit, but it quickly rebounded: In both the first and second quarters of this year, for example, real value-added in manufacturing—overall and for durable goods—hit all-time highs, easily surpassing their pre-pandemic quarterly records:

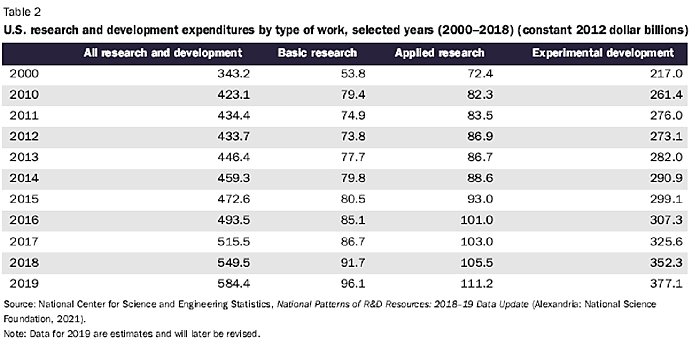

Particularly relevant for this hearing is domestic spending on capital expenditures and research and development (R&D). Here, the U.S. manufacturing sector again hit record levels before the pandemic, as did nonresidential fixed investment and R&D spending for the nation as a whole. Indeed, the latest data from the National Science Foundation show that all forms of R&D expenditures—basic research, applied research, and experimental development—hit inflation-adjusted records in 2019, driven by the private sector:

Now, with the pandemic mostly in the rearview mirror, businesses’ capital spending on software, R&D, equipment, and other productivity-enhancing items has taken off again:

In fact, economists with Morgan Stanley predict that U.S. capital spending will hit 116 percent of pre-recession levels by 2024—a rebound that took 10 years following the Great Recession.

By contrast, both the declining number of U.S. manufacturing jobs and the manufacturing sector’s shrinking share of gross domestic product tell us almost nothing about the sector’s health. This is because these trends primarily reflect long-term, global dynamics that are shared by most industrialized nations—including ones such as Germany and Japan with active industrial policies and trade surpluses—and are disconnected from specific federal economic policies, whether they are free market or interventionist. Instead, historical trends in U.S. manufacturing jobs and the sector’s GDP share are a standard story of economic development that all countries eventually experience as their citizens get richer and devote more of their budgets to services.

Second, there is little to suggest that economic isolationism or industrial policy would durably benefit either American manufacturing or the economy more broadly. The history of U.S. industrial policy shows, for example, that government attempts to achieve strategic, market-beating commercial outcomes routinely suffer from a lack of knowledge about the future of a chosen product or industry; a lack of formal or practical checks on political influence; a lack of disciplines on project budget, scope, direction, or duration; a lack of consideration of pre-existing policies, such as Buy American rules or the National Environmental Policy Act, that slow or derail projects, turning theoretical successes into costly real-world failures; and a lack of a thorough and comprehensive accounting of a project’s seen and unseen costs.

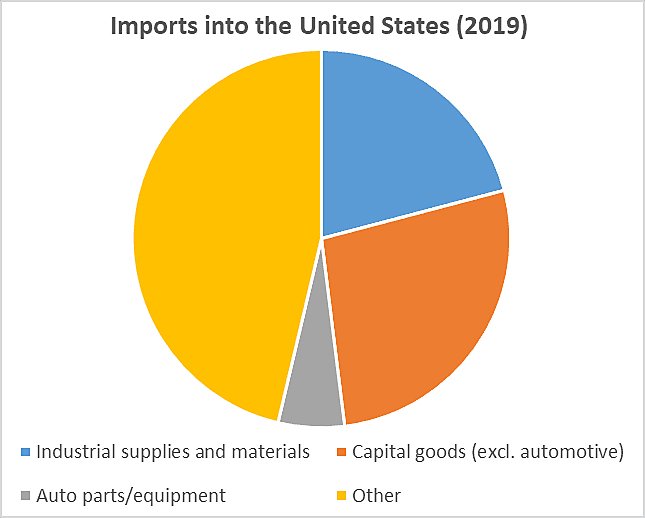

Even more troubling is evidence showing that U.S. industrial and other economic nationalist policies have undermined their very own objectives. In The Technology Pork Barrel, for example, the authors show that the failed Clinch River breeder reactor project “absorbed so much of the R&D budget for nuclear technology that it probably retarded overall technological progress.” Decades later, similar concerns arose again: Federal grants and loans to manufacture “green” goods, such as solar panels and electric vehicles, were found to have crowded out private investment in those same technologies, while other reports indicated that potential subsidy beneficiaries diverted resources from their actual businesses to obtaining federal benefits, thus undermining the former. In just the last few years, studies have shown that U.S. tariffs on metals and Chinese imports, allegedly implemented to boost American manufacturing, have deterred domestic investment and reduced U.S. industrial output and employment—a disappointing but entirely predictable result, given that roughly half of all imports into the United States are inputs and capital goods used by U.S. manufacturers to make globally-competitive products:

That the tariffs remain in place despite these and other problems (and statements from the Biden administration acknowledging some of them) is a cautionary tale regarding the unfortunate durability of industrial policy failures.

Third, the last 20 months of pandemic-induced turmoil show that there is no simple cure for global economic shocks, and certainly not ones that rely on reshoring supply chains or top-down economic planning by a new government agency. Global supply chains and a nation’s openness to trade and investment inevitably involve a risk that a “shock”—war, pandemic, natural disaster—hits the world or certain key nations and roils domestic supplies. Such issues surely have arisen since last year, as has been widely reported.

Far less reported, on the other hand, is how the U.S. and global manufacturing sectors immediately began adjusting to whatever supply chain challenges arose. There is perhaps no better example than the medical goods in such short supply early last year. According to a December 2020 U.S. International Trade Commission (ITC) report, U.S. manufacturers and global suppliers acted quickly to procure or produce new drugs, medical devices, personal protective equipment (PPE), cleaning supplies, and other goods in high demand. (Particularly “resilient,” in the ITC’s own words, were the U.S. pharmaceutical, medical device, N95 mask, and cleaning products supply chains.) The commission’s findings have been supported by reams of anecdotal evidence of U.S. investors, producers, and importers jumping to produce medical and other essential goods during the pandemic. By January 2021, in fact, members of Congress were writing President Biden to complain of a potential glut of American-made PPE!

Such events are not only a testament to the tireless work of manufacturers, retailers, and logistics professionals throughout the pandemic, but also a cautionary tale for U.S. policymakers: By the time Congress decides to intervene in a certain market, it will look much different than the one on which that decision was based, and it will change again by the time any government-supported production comes online.

Furthermore, while reshoring supply chains might have insulated U.S. producers and consumers from external supply and demand shocks, those same policies can amplify domestic shocks and reduce overall economic growth and output to boot. Such a risk emerged earlier this year when unprecedented cold hit Texas: several U.S.-based semiconductor manufacturers were forced to idle production capacity, thus exacerbating the very chip shortage that is today often blamed on “globalization.” A few months later, we learned from the New York Times that Germany—a nation more focused on manufacturing than the service-oriented United States and often a model for a new American industrial policy—has suffered greater economic disruptions because of its “dependence” on manufacturing and goods exports. Both experiences are consistent with past research showing that manufacturing and mercantilism are not an easy recipe for economic resiliency; that domestic economic shocks can cause the same supply chain problems as foreign ones; and that the diverse U.S. economy is not nearly as vulnerable to global economic turmoil as is often claimed.

Finally, future government action on U.S. manufacturing competitiveness should focus not on trying to outsmart the market or deliver targeted federal grants or loans to privileged companies and workers, but instead on broadly emphasizing economic openness, diversification, and flexibility. Policies liberalizing trade and foreign investment would support U.S. manufacturing competitiveness and economic resiliency by improving companies’ access to and production of essential goods. Reforms should go beyond simple tariff relief and instead focus on making it easier for businesses to locate and invest in the United States. Studies repeatedly show, for example, that foreign direct investment in the United States benefits not only targeted projects and workers, but also surrounding companies and communities. BEA data further show that U.S. affiliates of foreign multinationals spend hundreds of billions of dollars per year in the United States on research and development and capital expenditures, with the biggest shares going to manufacturing. Other analyses of foreign affiliates in the United States show that they pay more, export more, and are more productive, on average, than similarly situated domestic firms.

Congress also should consider other “horizontal” economic reforms that would boost U.S. manufacturing competitiveness. Most notably, the federal government should significantly expand high-skill immigration, past U.S. restrictions of which have been shown to encourage multinational corporations to offshore jobs and R&D activities to affiliates in more welcoming countries and to benefit potential U.S. adversaries, especially China, in terms of new jobs, new businesses, and new innovations. The government should also further lighten corporate tax and regulatory burdens to encourage innovation and foreign investment and to ensure that businesses already here can remain globally competitive. This includes expanding and making permanent the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act’s temporary “full expensing” provision (“100 percent bonus depreciation”), which allows U.S. businesses to write off certain business investments immediately and fully.

In conclusion, both recent experience and scholarly research show that federal government attempts to subsidize “essential” industries or reshore supply chains carry significant risks, and that open markets can bolster U.S. resiliency and competitiveness by increasing access to critical goods, services, and workers, mitigating the impact of domestic shocks, boosting economic growth, and facilitating rapid, market-based adjustment in times of severe economic uncertainty. This argues for a different approach to achieving real economic resiliency than the ones primarily under consideration today—an approach based not on China’s state capitalist model but instead on the open and flexible policies that America does best.