Before we begin, a quick apology for Capitolism’s delayed delivery this week: The president’s (very bad) tariffs have kept me rather busy (and annoyed). I’ll handle them next week—don’t worry, they’re (unfortunately) not going anywhere. Now, on to the show.

Anyway, as frequent readers probably know by now, I’m a pretty big sports fan. Certainly not the biggest fan—not like these lunatics, I mean—but still pretty big. When the Texas Rangers finally won the World Series last year, for example, I may or may not have been fighting back tears when I called my dad after the final out. And don’t even get Mrs. Capitolism started on my TV viewing habits during various sports seasons (please, don’t). So, if there’s any economics-minded person out there who might possibly be open to governments subsidizing big, admittedly cool U.S. sports venues, I’m probably your guy.

And yet… no.

Instead, the harsh reality for even the biggest sports fan is that arena subsidies are a terrible use of finite government resources and a ridiculously egregious redistribution of wealth from regular Americans—fans and haters alike—to some of the wealthiest people and organizations on the planet. And, to top it all off, they’re a classic case of political malpractice—local officials delivering massive rents to various cronies by promising unwitting voters the world yet delivering far fewer—but still “seen”—economic and social benefits to their communities.

Yet the subsidies persist, and—despite some recent high-profile losses in Kansas City, Virginia, and Arizona—the problem might actually be getting worse.

Skyrocketing Subsidies

The recent subsidy rejections have led some optimists to wonder, in the words of Pro Football Talk’s Mike Florio, whether “the ship might be sailing on taxpayer money for NFL stadiums” and other pro sports venues. But these welcome failures unfortunately don’t yet appear to be part of a wider turn against the subsidies. According to The Atlantic, for example, “America finds itself on the brink of the biggest, most expensive publicly-funded-stadium boom ever”—a boom that includes staggering sums for arenas in Las Vegas (“more than $1.1 billion in public funding, not counting tax breaks” for a baseball stadium); Chicago (owners seeking $1 billion for a baseball stadium and $2.4 billion for a football stadium); Cleveland ($600 million for football); Buffalo ($850 million for football); and Nashville ($1.26 billion for football).

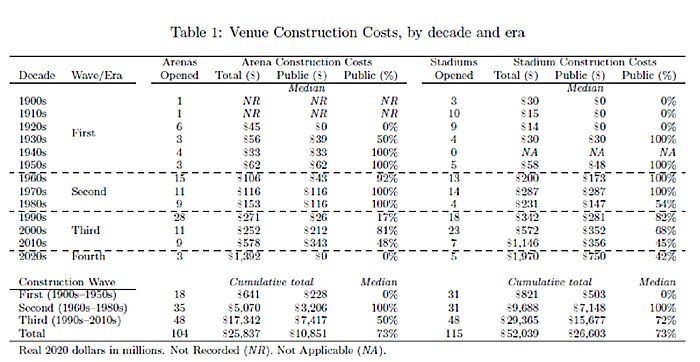

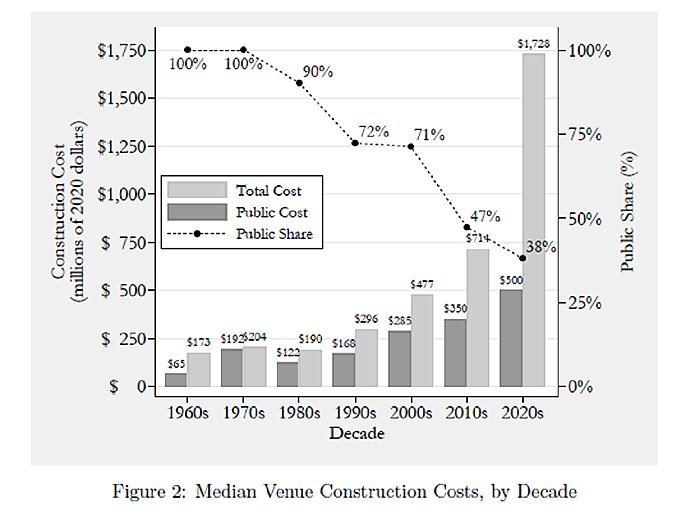

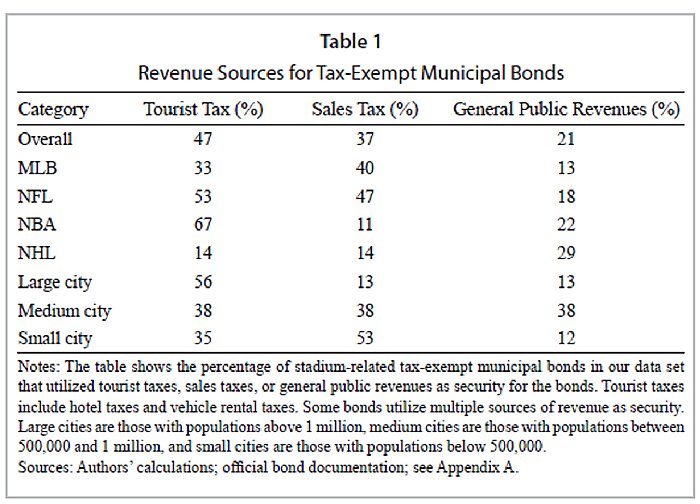

This “boom“ is part of a broader historical trend of ever-increasing subsidy payouts. As documented in a recent paper from economists J.C. Bradbury, Dennis Coates, and Brad Humphreys, direct government subsidies for the construction of professional sports venues have increased substantially over the last 50-plus years, from a total of around $10 billion in the 1960s-80s to more than $23 billion in the 1990s-2010s (adjusting for inflation):

The authors show that this increased government spending is owed to the fact that sports venues have (as anyone who’s recently visited one of these places can attest) gotten more extravagant and expensive over time—a trend driven at least in part by generous subsidies. Put simply, it’s easier for team owners to pay for and justify that fifth HD Jumbotron and the concourse art gallery when city hall’s paying. Thus, even though governments are today picking up a smaller share of the stadium construction tab (dotted line below), they’re still paying much more per facility (dark gray bar) because the tab itself (light gray bar) has gotten so much bigger:

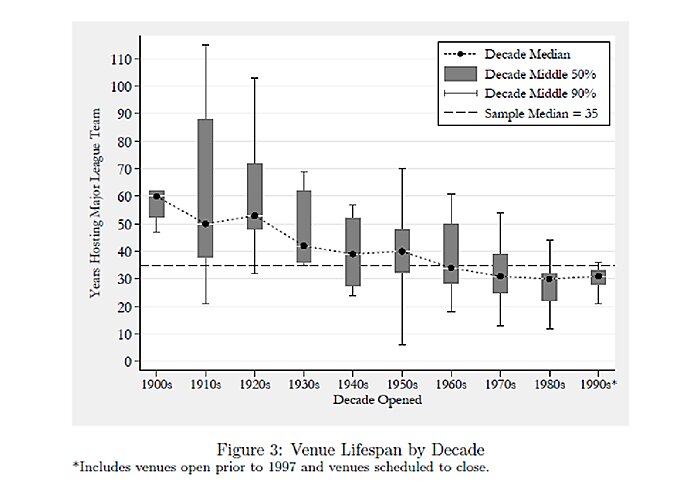

Given recent commitments and expenditures, we can expect spending in the 2020s and beyond to increase accordingly—and to do so more quickly because sports venues’ lifespans are shrinking, as teams have become more motivated to replace old venues with new ones because the latter get more attendance and league attention (aka the “novelty effect”):

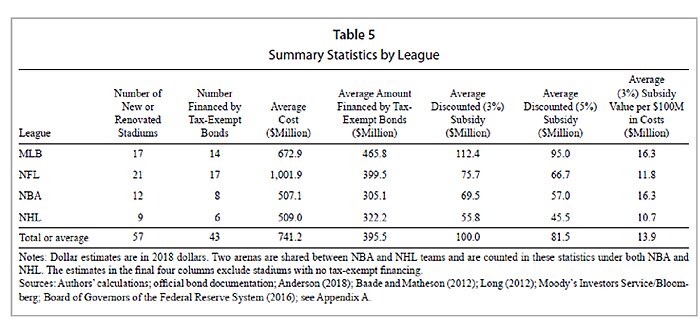

And these dollar figures are just subsidies toward publicly reported capital construction costs. As Bradbury and colleagues note, there are other, “less obvious public contributions from land, infrastructure improvements, maintenance and operations, and tax abatements” that are often not reported and, per other studies, can increase total subsidy amounts by 25 percent to 40 percent above reported costs. For example, the construction of Gillette Stadium in Massachusetts received no direct public funding, but the New England Patriots still got $70 million in state-provided infrastructure around the venue. A 2023 study found that U.S. professional sports facilities have received $18 billion in property tax breaks. And a 2020 Brookings Institution paper estimates that between 2000 and 2020 these venues got about $4.3 billion more in federal subsidies via tax-free municipal bonds.

The Brookings paper adds that common financing vehicles for sports venues—used to qualify bonds for the federal tax exemption—raise further concerns. In particular, both “tourist” taxes on hotels and rental cars (47 percent of analyzed stadiums) and sales taxes (37 percent) are highly regressive: They burden poorer residents more than wealthier ones, while “the benefits provided by the subsidized stadiums accrue primarily to the wealthy.” Using these taxes for sports venues also makes those same revenue sources unavailable for other uses in the city (opportunity costs strike again), and “only a tiny fraction of the hotel rooms or rental cars used in a city over the course of a year are purchased by sports tourists.”

All told, U.S. pro sports stadiums and arenas have benefited from tens of billions of dollars in public spending (direct subsidies, forgone tax revenue, and miscellaneous other spending) and new, mostly regressive taxes in just the last two decades. That’s a lot of money.

And Sports Venues Are Very Bad Deal for Taxpayers

Maybe all this government support might be worth the costs if the subsidized facilities at issue produced even a fraction of the benefits that supporters promise, but they don’t. Instead, there are few positions on which more economists agree than the terribleness of sports arena subsidies. A 2022 paper by Bradbury and his same colleagues documented the consensus by summarizing more than 130 studies on the issue over the last 30 years, looking at not just the facilities’ direct pecuniary benefits but also indirect and intangible ones like “civic pride.” Their conclusion is unequivocal:

[block] First, and perhaps most important, nearly all empirical studies find little to no tangible impacts of sports teams and facilities on local economic activity, and the level of venue subsidies typically provided far exceeds any observed economic benefits. In total, the deep agreement in research findings demonstrates that sports venues are not an appropriate channel for local economic [development]. Any identified economic effects typically occur in the area immediately surrounding stadiums and arenas; however, spatially concentrated impacts are not always present and thus they can not be generally applied to all stadium projects. No evidence of supporting broad metropolitan-level effects exists, indicating that sub-local (neighborhood) effects are not equally distributed in host jurisdictions.[block]

Put more simply, any “seen” local gains that pro sports venues generate are offset—sometimes more than offset—by “unseen” losses in the same metropolitan areas. Thus, the facilities can’t possibly justify the amounts of public subsidies involved. A recent Bloomberg piece explains this phenomenon well:

Team owners and their backers think of stadium and arena developments as a kind of perpetual-motion machine, driving so much economic activity that they sustain themselves. The problem with this model is that most venue sales come from people who live locally, so that economic activity is simply reallocating commerce from somewhere within the jurisdiction. Instead of going out for a drink at a pub, the boys might meet up for a hockey game. Instead of buying groceries and making dinner, a family might grab hot dogs at the ballpark. That’s a problem for an arena to be financed by bonds and repaid by tax revenue…since an arena mostly shifts that tax revenue away from other local sources.

Games do draw out-of-town fans, which is a net benefit. Capital One Arena, nestled in the heart of the DMV, brings in Capitals fans from Virginia and Wizards fans from Maryland (and vice versa). But arenas also disrupt other kinds of local economic activity, which is a drag. On game days shoppers might avoid the Target department store in Potomac Yard (if it sticks around). Nobody builds a grocery store or dentist’s office near a ballpark. Alexandria residents may avoid even going near the area due to traffic.

This result is, as Bradbury’s team explains in their 2023 paper, basic economic theory and classic Bastiat: “To view stadium-related spending as new spending commits the basic economic fallacy of ‘the seen and the unseen,’ confusing observed concentrated spending at sports events as new spending, without accounting for the opportunity cost of reduced spending owing to other local merchants, which is difficult to observe because of the broad dispersement of lost revenue across many businesses.” It’s just shuffling the economic deck chairs.

One needn’t, however, be up on his 19th-century economic theorists to know that subsidized sports venues are a bad deal for taxpayers. Aside from a few high-profile exceptions, local news is replete with examples of subsidized boondoggles never generating the benefits local taxpayers were promised. Here’s Bloomberg again with one recent episode:

The Braves pitched suburban Cobb County on a $672 million ballpark to anchor a $1.3 billion mixed-use development, funded with about $300 million in public financing. Former Cobb County Chairman Tim Lee described it at the time as the “biggest economic development deal in our county’s history.”… But according to a 2022 study by Bradbury, the Braves complex has been a money drain. Since its opening in 2017, Truist Park has operated at a deficit of $15 million per year — a particularly bad showing for a ballpark during its “honeymoon” period.

My colleagues at the Cato Institute have documented many, many other arena subsidy failures over the years. In case after case, subsidized sports venues are shown to be a very bad deal for the Americans forced to pay for them. And no amount of glitz and misdirection can change that fact.

They Don’t Need the Money

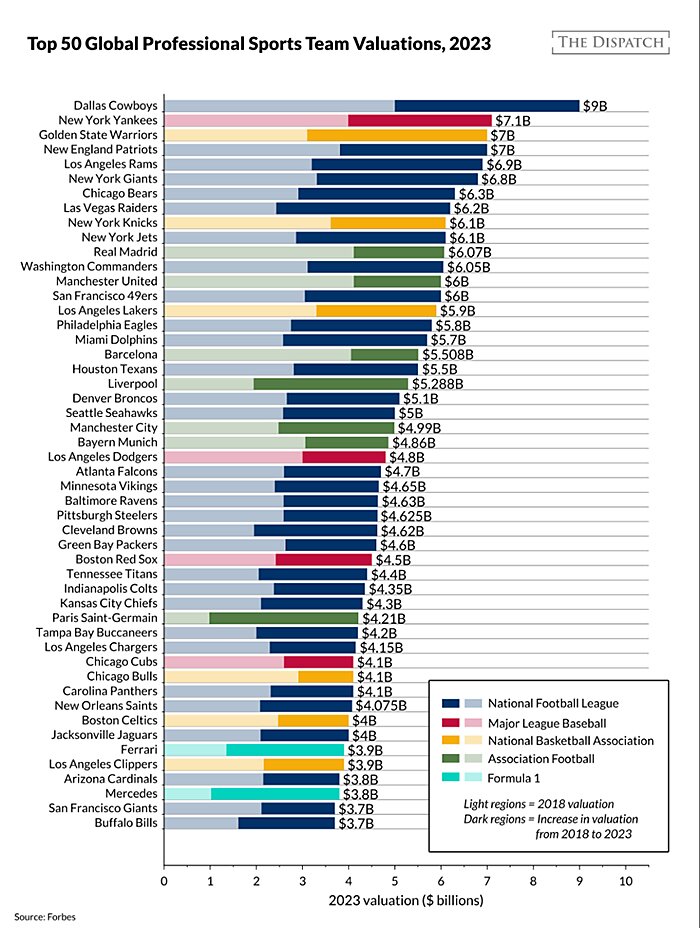

Finally, and not to go all populist-pitchforky on you here, but it’s important to note that the recipients of this public largesse aren’t exactly paupers. According to Forbes, for example, as of 2023 the top 20 professional sports team owners on the Forbes 400 list of the world’s wealthiest people are worth a collective $382 billion, and “for most, the NFL, the NBA and MLB remain a very lucrative side hustle.”

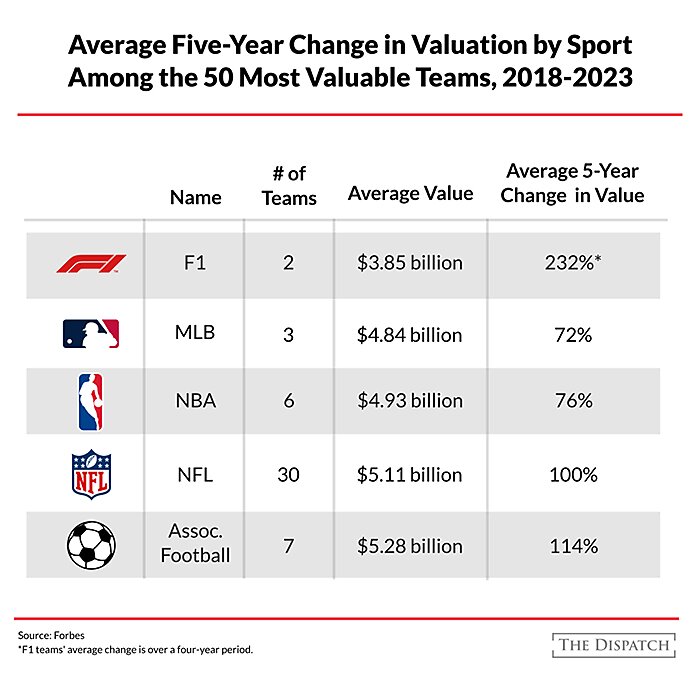

The teams themselves are also, per Forbes, money-printing machines: “The world’s 50 most valuable sports teams are now worth a combined $256 billion (an average of $5.12 billion), 15% more than a year ago. And this year’s cutoff is higher than ever—$3.7 billion, or an increase of 19% from 2022.”

Professional sports leagues are also more valuable than ever:

The teams’ and leagues’ various media and advertising contracts—broadcasting rights, stadium/arena naming rights, official sponsors, etc.—are similarly lucrative and, again, getting even more so: “Until the broadcast contract ended in 2013, the terrestrial television networks CBS, NBC, and Fox, as well as cable television’s ESPN, paid a combined total of US$20.4 billion to broadcast NFL games. From 2014 to 2022, the same networks paid $39.6 billion for exactly the same broadcast rights.” (Per the same article, the MLB and NBA have enjoyed similar gains; only the NHL has regressed—and, seriously, who really cares about hockey?)

Economics and hockey jokes aside, these are simply not people and organizations that need taxpayer help.

So, Why Do We Keep Doing It?

The ironclad case against subsidies raises the obvious question of why they persist. Here, I see two big reasons. First, there’s the aforementioned “seen versus unseen” dynamic. As Bastiat explained almost two centuries ago, most people recognize the visible benefits of government actions while ignoring their invisible costs. Thus, it’s perfectly natural (annoying, but natural) for voters to reward elected officials who provide subsidies that generate tangible and highly visible outputs—stadiums, arenas, and the like—while missing those same projects’ many hidden costs, especially opportunity costs like forgone tax revenue and lost economic activity. Research further shows that voters reward politicians for even trying to subsidize stuff (in the study’s case, corporate investment), so politicians have a strong incentive to do just that. And local sports fandom—passion for not just the team but the community to which it’s attached—surely amplifies many voters’ responses to subsidy plans. Superfans might not reward a politician for subsidizing some random company but probably will for the team they grew up cheering.

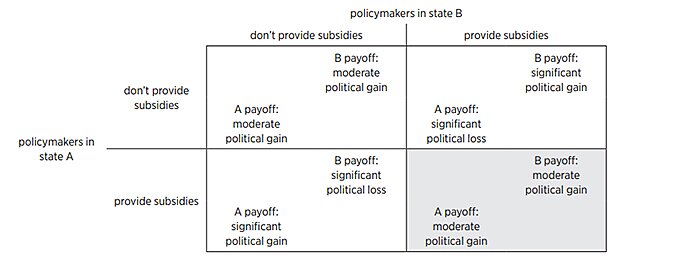

Second, stadium subsidies create a classic “collective action” problem for local governments forced to compete for intentionally scarce professional sports teams. (Here’s a recent example.) As Bradbury, et al note, “Strong consumer preferences for local franchises and the restriction of competitive alternatives provides owners the opportunity to pit host markets against each other to extract substantial subsidies from residents through relocation and relocation threats.” This creates a classic “Prisoner’s Dilemma” situation, in which two guilty prisoners being interrogated by the police would go free if they stayed silent, but, because each can’t be sure the other will keep his mouth shut, both end up confessing to minimize their jail time. Many economists and political scientists have applied this framework to corporate relocation incentives and two hypothetical legislatorsfrom different states. The optimal outcome for both would be to withhold subsidies, but because each legislator has no way of ensuring that the other will abstain and because one’s support of subsidies will make the abstaining politician lose votes/support, they both offer subsidies. Here’s the choice in chart form:

This dynamic is amplified by sports teams for reasons already mentioned. Urban studies guru Richard Florida explains:

The threat of moving a team puts cities and their mayors on the proverbial hot seat: They can either ante up the dough or watch their fan’s beloved team go elsewhere. As Stanford University’s Roger Noll, a leading expert on sports economics, points out: “Cities have very little bargaining power with an NFL team. As long as there are cities without NFL teams that are willing to subsidize a stadium, cities will have to pay part of the cost of a new stadium.” What mayor or council wants to be on the hook for that? Supporting billionaire owners may look bad, but sitting idly while the local team moves to another city can also mean getting tossed out of office.

Good luck breaking that dynamic, folks—no matter how truly awful the case against subsidies may be.

Chart(s) of the Week