Dear Capitolisters,

I hope you all had a nice [winter holiday of your choosing]. Instead of doing a 2022 retrospective like I did last year, the first Capitolism of 2023 will look forward to some of the biggest (IMO) unanswered questions for U.S. economic policy in the year ahead.

Will the U.S. See a Real Recession?

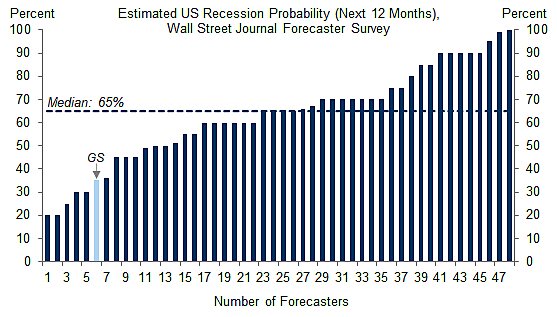

As we discussed back in August, mid-2022’s “recession” was more a statistical quirk than a real recession, and the rest of the year reinforced the point, with U.S. labor market, gross domestic product, and other figures consistently beating expectations through the fall (much to the dismay of the inflation-fighting Federal Reserve). This year could be different: As of now, a significant majority of economists expect the Fed’s current tightening cycle to tip the economy into a recession within the next 12 months:

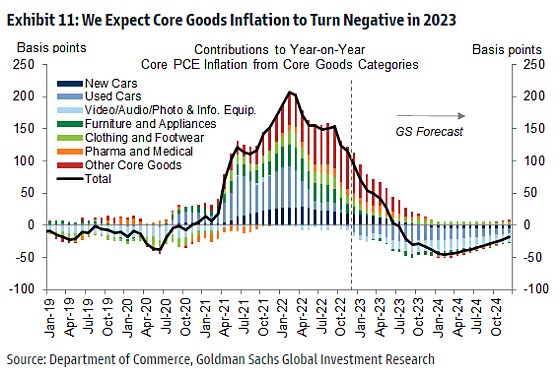

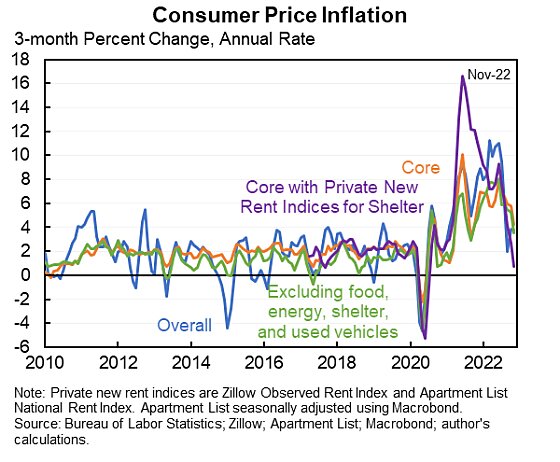

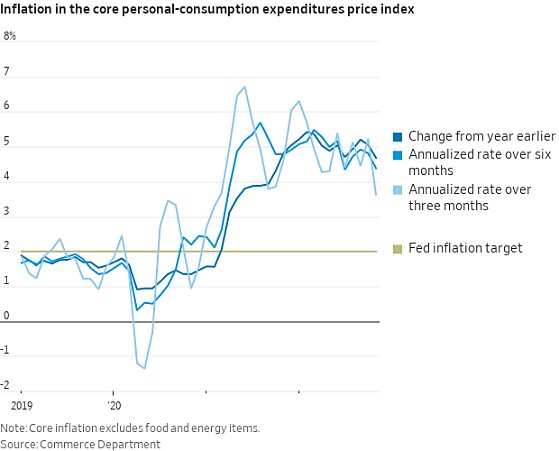

As the figure above indicates, however, several forecasters—including the folks at Goldman Sachs (GS) who made the chart—remain unconvinced that a recession is likely. They instead believe that the Fed can achieve its much-desired “soft landing”: hiking interest rates just enough to temper demand and inflation without a major spike in unemployment and related decline in economic activity. The most recent inflation data (for November) came in cooler than expected, boosting the Goldman/optimist view:

However, Fed Chair Jerome Powell and his colleagues aren’t yet convinced that the economy has sufficiently cooled off, so they remain committed to further tightening. That raises the risk of the Fed’s coming rate hikes actually overshooting what’s needed to quell inflation and thus causing a recession this year. Given the latest data, I think both the hawks and the doves make good points (with the latter probably a smidge ahead today), and I don’t envy the Fed for having to thread the needle this year. We shall see.

Will Retirees Unretire?

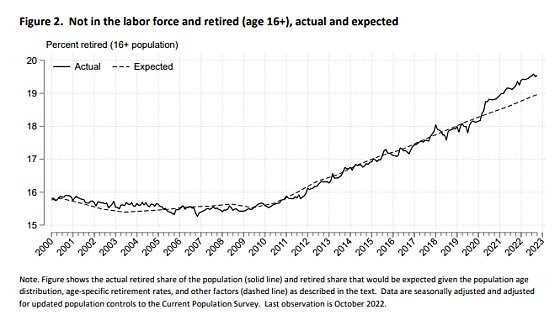

A big part of the current recession/inflation puzzle is something I discussed way back in October 2021 [ed. note: Capitolism readers can see the future!]: the surge in pandemic-related early retirements and its potential effect on the U.S. economy. Back then, it was truly an open question as to whether COVID’s retreat and dwindling savings would motivate older Americans to return to the labor market (and thus help to cool it off and temper U.S. inflation concerns). More than a year later, few have jumped back in. According to a December 2022 paper from the Federal Reserve, for example, the last three years saw about 3.5 million Americans retire, with almost half of those (1.6 million) deemed “excess retirements” caused by the pandemic instead of natural attrition:

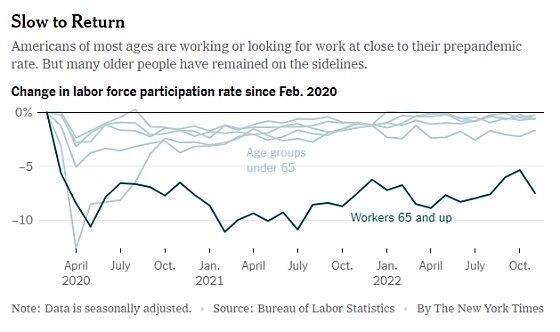

The paper notes that these retirements are concentrated among workers around age 65, and that the labor market should eventually normalize as these “early retirees” reach the age at which they would’ve retired anyway (unless we’ve entered a new normal of early retirement, which seems unlikely). In the near term, however, lack of “un-retirees”—especially those in their 60s—is, per a recent New York Times piece, making the Fed’s job much more difficult:

If America’s missing workers were just temporarily sidelined, waiting to spring back into jobs given enough opportunity and a safe public health backdrop, nagging labor shortages might fade on their own. But if many of the workers are permanently retired — as policymakers increasingly believe is the case — bringing a hot labor market back into balance will require the Fed to push harder.

It can do that by raising rates to slow consumer spending and business expansions, tempering the economy and slowing hiring. But the process is sure to be painful and could even spur a recession.

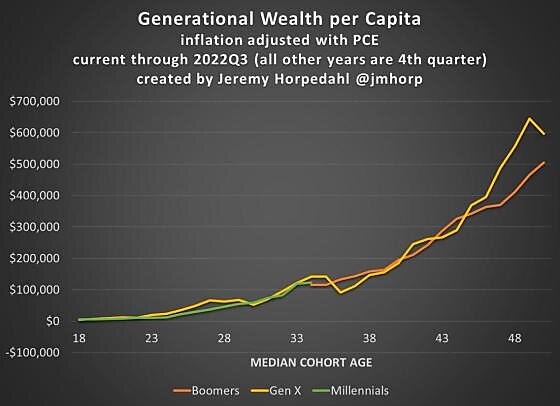

Unlike after the Great Recession, moreover, these retirees may be older boomers and/or have fatter nest eggs—making their return to the labor market less likely than a decade ago (when a lot of retirees did return to the labor market). “The demographic decks were always stacked for boomers to leave the labor market soon,” the Times notes, “but the pandemic seems to have nudged people who might otherwise have labored through a few more years over the cusp and into retirement.” If they stay there in 2023—and barring a miraculous increase in immigration (sigh)—U.S. labor supply will likely remain depressed, and the Fed may therefore have to push harder to cool labor demand, thus making a painful recession more likely.

[Cue more grumbling from me about U.S. immigration policy.]

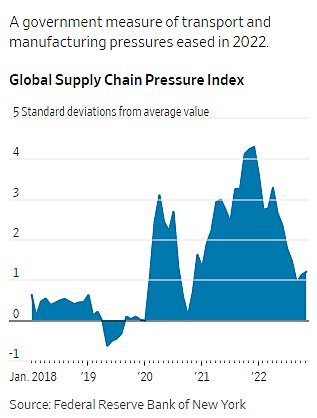

Also as I predicted last year, early 2022’s much-ballyhooed “Death of Globalization” fizzled out in the second half of the year, as supply chains normalized (see chart below), trade volumes actually expanded, investment in global logistics tech soared, and the conventional wisdom (and more detailed analysis) caught up to my early assessment of “reglobalization, not deglobalization.”

That said, plenty of uncertainty remains for global trade and supply chains in 2023. Most obviously, the Russia-Ukraine (hot) and U.S.-China (cold-ish) conflicts, as well as increased skepticism of China (see below), will continue to reshape trade flows in not only expected ways (e.g., more liquified natural gas exports and more manufacturing in China alternatives like Mexico, Vietnam, or India), but also unexpected ones. Demand for goods will also likely take a hit, thanks to swollen inventories, shifting consumer tastes, and central bank inflation-fighting efforts. Still-unfinished labor negotiations for West Coast ports could cause other snarls (though companies have worked to mitigate some of the potential blowback). The 2022 expansion of industrial policy here and abroad, along with the U.S. government’s depressing (and somewhat unique) turn against globalization, could generate disputes and tit-for-tat protectionism, further confounding the trade recovery. American politicians also seem to have learned absolutely nothing from the infant formula debacle (and others), at least when it comes to protectionism and “supply chain resiliency.” And it’s far from clear how China’s new (and inexplicable) “damn the torpedoes” approach to COVD-19 will affect both global supply of and demand for commodities and manufacturers in 2023.

Supply chains should enter a new and calm(ish) normal in 2023, giving consumers and central bankers some relief. If, on the other hand, a few of the things above go sideways? Buckle up (again).

Will Washington’s Big Tech Hysteria Fade?

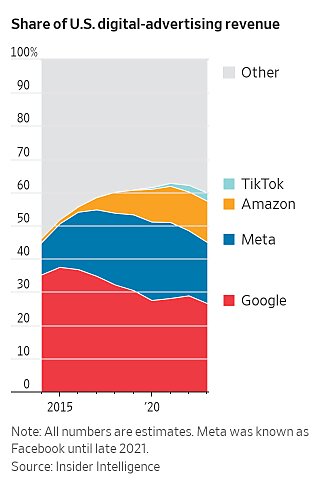

One of my running gags on Twitter in 2022 was to preface news stories on Big Tech’s many struggles—financial woes, layoffs, declining sales or market share, etc.—with “MONOPOLY WATCH:” to highlight the industry’s real-world dynamism and to poke fun at persistent (often hysterical) Beltway claims that Facebook and other large tech companies were obvious and unstoppable monopolies in urgent need of new regulation. As we discussed here in May, antitrust skeptics had lots of opportunities to make this joke in 2022, as Big Tech’s luster faded in the face of Fed rate hikes, new competition (for sales and talent), disappointing financial results, and whatever Elon Musk is doing with Twitter (your guess is as good as mine). Meanwhile, bipartisan legislation subjecting the industry to new antitrust regulation failed to become law, and we learned over the break that one of the Biden administration’s top antitrust hawks, Columbia Law School’s Tim Wu, will step down today (citing the lack of new antitrust law as “disappointing”). Thus, it may be that Washington’s (misguided, IMO) crusade against Big Tech will fade in 2023.

On the other hand, “Big Tech” remains a useful political foil for both populist Republicans and Democrats, and the recent crypto implosion (including possible criminal activity by FTX’s fallen wunderkind Sam Bankman-Fried) could fuel new government scrutiny beyond merely crypto and “fintech.” The Biden administration isn’t exactly giving up on its Big Tech crusade, either. As the New York Times notes, for example, Wu was merely “one-third of a troika—along with Lina Khan at the Federal Trade Commission and Jonathan Kanter at the Justice Department—leading Washington’s attempts to more aggressively check corporate giants, including the largest tech companies.” Thus, even if legislative vehicles remain stalled, unilateral broadsides against the already hobbled industry could continue in 2023, with significant economic and political repercussions.

Where Will Remote Work Settle?

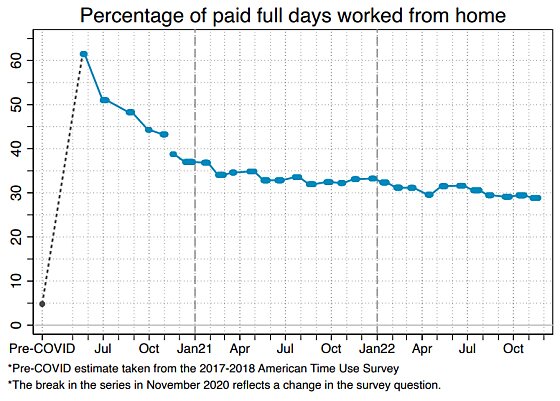

As readers, Remnant listeners, and Twitter followers know, the pandemic-era explosion in remote work has been an obsession of mine and earned its very own chapter in my new book (which is now available on Amazon). Therein, we focused on the rise of remote work (from about 5 percent of paid workdays to about 30 percent today), its benefits for many (not all!) workers and employers, and some practical reforms to eliminate current, mostly unintended discrimination against remote work in the United States.

With American life basically back to “old normal” and various remote work metrics—work/commute hours, job openings, worker preferences, etc.—stabilizing at “new normal” levels, it’s safe to say that the coming years will see far more remote or hybrid work than we saw in pre-pandemic times.

Beyond that, however, there’s a ton of stuff to work out. Most obviously, employers and employees are still sorting through remote work offerings and demands: While some companies and industries appear eager and able to embrace full-time remote work, many others are tentatively choosing hybrid models or even calling everyone back into the office full time. Data on how remote work affects worker productivity, promotion, and satisfaction are also still incomplete (though initial data are mostly positive).

How remote work stabilizes in 2023 could affect all sorts of other things, such as:

- Geography: Will trendy places far removed from major urban centers deflate, and will suburbs and exurbs further inflate, if hybrid work (requiring workers in the office every week) becomes the preferred model? Will “superstar cities” like New York and San Francisco get their mojos back as desirable places to live (regardless of work)? Will “rising star” cities like Raleigh or Columbus—fueled in part by remote work—face the same challenges (e.g., high housing costs) that their superstar predecessors faced?

- Real estate: Where will residential real estate prices settle in areas suddenly made attractive by remote work options? Can developers and policymakers figure out how to surmount the economic and regulatory hurdles limiting the conversion of less-needed commercial real estate to much-needed residential offerings?

- Public transit and infrastructure: How will public transit systems deal with decreased ridership? How will infrastructure spending and construction change with fewer people commuting every day?

Another indicator that #WFH is permanent: public transit journeys stabilizing at 35% below 2019 levels.

— Nick Bloom (@I_Am_NickBloom) December 29, 2022

This raises concerns over the survival of public transit systems. Costs are heavily fixed — think train and subway networks — but revenue is way down with 35% less journeys. pic.twitter.com/JnJtuPYCg5

- Mobility: Will new remote workers choose to move long distances or stay closer to home (some early data, perhaps surprisingly, indicates limited interstate mobility)? Will business travel increase (e.g., more remote worker trips to the home office) or decrease (e.g., fewer client meetings)?

- Fertility: Will the surprising uptick in births among college-educated women—fueling the first U.S. “baby bump” since 2007 and fueled by remote work—continue?

- Technology: How will hardware and software innovate to meet the needs of remote workers and their employers, and what technologies/companies will be the big winners? (“For example, research … finds that the share of U.S. patent applications for technologies that advance remote-work capabilities has doubled since early 2020, and it remains on an upward trajectory.”)

- Policy. Finally, I’d be remiss not to mention the various policies—especially state and federal tax rules—that haven’t kept up with the remote work boom. As remote work remains popular and prevalent, will policymakers finally get around to fixing these problems?

Will the Authoritarians Strike Back?

Finally, I was pleased to see the second half of 2022 feature much more skepticism among Western elites regarding the long-term threats posed by authoritarian regimes around the world—including and especially China. For example:

Paul Krugman: “Exactly how China’s bubble will end isn’t clear—it might be a sharp slowdown, or it might be a period of ‘low quality’ growth that masks the true extent of the problem, but it won’t be pretty.”@paulkrugman https://t.co/FHptDbqHF3

— Jonathan Cheng (@JChengWSJ) December 24, 2022

Surely, the CCP and its counterparts in Iran, Russia, and elsewhere can and will pose challenges for Western governments and the world, but their myriad, systemic flaws and headwinds—ones some folks (ahem) have been noting for years now—quickly became conventional wisdom last year, thanks in no small part to China’s zero COVID debacle and Russia’s epic meltdown in Ukraine. Now, people are digging deeper into China’s demographic problems, its economic troubles and missteps, its state capacity, and even its much-ballyhooed (and ‑coveted) industrial policy. And they’re not liking what they find.

But still, these things tend not to move linearly, and it’s certainly possible that at least one big authoritarian regime, if not several, mounts a comeback in 2023. I unsurprisingly remain skeptical of their long-term staying power—at least as a major global threat requiring the U.S. to hunker down and abandon open, Western-style capitalism—but in the short term? Look out.

Other Questions

These are just a few of my big 2023 questions, but I’ve droned on long enough. Other big ones, I think, include:

- Will artificial intelligence (e.g., the much-discussed ChatGPT) move from a fun parlor trick to a widely used professional tool, and, if so, how will that affect certain now-automatable jobs (e.g., rudimentary legal work)?

- Will the four-day workweek catch on (no, seriously)?

- Will Congress do anything constructive on immigration?

- How will all that U.S. industrial policy shake out?

And, finally, what unknown and unknowable development will captivate U.S. economic policy and drive the bus for much of 2023? If the last few years have taught us anything, it’s that we should expect the unexpected when it comes to the global economy—and that may make this 2023 question the biggest one of them all.

Chart(s) of the Week

Corporate Greedometer: Off! (via Goldman-Sachs—no link, sorry)