“If [policymakers] err on the side of inflation, there will be widespread complaining about rising prices to be sure, but that diffuse message is quite drowned in the rising babble of specific demands and concrete proposals from identifiable interest groups — to compensate me, to regulate him, to control x’s prices, and to tax y’s “excess profits”, etc.” Axel Leijonhufvud, 1975

“What lies at the base of the whole effort to fix maximum prices? There is first of all a misunderstanding of what it is that has been causing prices to rise. The real cause is either a scarcity of goods or a surplus of money…the political support for such policies [price controls] springs from a…confusion in the public mind. People do not want to pay more for milk, butter, shoes, furniture, rent, theater tickets, or diamonds. Whenever any of these items rises above its previous level the consumer becomes indignant, and feels that he is being rooked.” Henry Hazlitt, 1946.

“The real danger does not consist in what has happened already, but in the spurious doctrines from which these events have sprung. The superstition that it is possible for the government to eschew the inexorable consequences of inflation by price control is the main peril.” Ludwig von Mises, 1952.

High inflation has resulted in some wild and damaging policy proposals during this presidential election campaign. The pinnacle perhaps came on 17 September, during a town hall in Flint, Michigan for former President Trump.

A month earlier, Vice President Kamala Harris had blamed corporate price gouging for families’ high grocery bills. Despite “food at home” prices having increased by just 0.9% over the preceding year, Harris echoed her former Senate colleagues Elizabeth Warren and Bob Casey in blaming greedy corporations for the 21 percent food price inflation seen overall since January 2021. The Democratic presidential candidate promised to sign an anti-price gouging law to help avoid grocery prices spiking during future “emergencies,” providing the Federal Trade Commission with a raft of new powers to go after stores deemed to be charging unconscionably high prices during crises.

This policy promise was the apex of the Democrats’ dalliance with kook “greedflation” narratives — the raft of bizarre theories about how corporate greed, market power, or collusion were the true drivers of the highest inflation since 1981. Professional economists, by and large, haven’t bought such arguments, and Harris faced swift and gratifying blowback from academics for proposing contextual price caps on groceries. Anti-price gouging laws, economists pointed out, were de facto price controls that risked producing food shortages, black markets, and inefficiency. Trump himself joined the chorus of criticism, bemoaning the prospect of Harris’s “socialist price controls.”

How and why both presidential candidates declared a war on market prices during this election campaign.

Yet, there, in Flint, Trump himself started embracing his own economically illiterate proposals for reducing voters’ living costs. Asked what he might do as president to lower food and grocery prices, Trump rambled about the need to restrict imports of food to protect farmers. How constraining the supply of food and reducing competitive pressure on domestic agricultural producers would lower prices is anyone’s guess. Trump was, in effect, arguing that he would reduce grocery bills by knowingly increasing them.

In case we thought this bad economics was an aberration, just a day later Trump said that he wanted to cap credit card interest rates at 10 percent. Both candidates for President are thus now advocating price controls – something anathema to economists given price caps’ long and destructive record.

In The War on Prices I had worried that, given the misguided debates over what had caused the recent inflation, the political conditions were such that extensive price controls and other misguided interventions would become appealing next time inflation hit. I was wrong. Those demands have already arrived in this election, even as inflation itself has receded.

Voters (Rightly) Hate Inflation

How the hell did we get to a position where such bad economic ideas were being advocated?

In some ways, it’s no surprise: inflation itself makes voters angry. Americans have a long tradition of demanding government action when prices are extremely volatile. And politicians often oblige. Carola Binder’s recent book shows that “foundational moments in American economic history – the establishment of paper money, wartime price controls, the rise of the modern Federal Reserve – occurred during financial panics as prices either inflated or deflated sharply.”

After years of relative price stability, the public found the recent high inflation incredibly jarring. The Personal Consumption Expenditures Price Index that the Federal Reserve targets is today 8.1 percent higher than we’d expect if it had been anchored at 2 percent annually – equivalent to Americans experiencing around an extra 4 years’ worth of inflation in that time frame than expected. The most observable consequence was on the dollar cost of essentials. On top of food being a fifth more expensive, rents are up 23 percent and electricity prices 28 percent.

While economists focus narrowly on “inflation,” the fall in value of the dollar unit, voters worry about their cost of living more broadly. Larry Summers and co-authors have pointed out that the tightened monetary conditions in reaction to inflation saw average 30-year fixed mortgage rates surge to over 7 percent, as car financing and credit card interest rates jumped too. This increased cost of borrowing money is understandably seen as a barrier to achieving major life ambitions for many households.

Given the scale of these cost shocks, it’s perhaps little surprise that “inflation” and “prices” have been seen by voters as the most important political issue during this election. Even as inflation has come down, trips to the grocery store are a painful reminder of just how much prices have jumped since 2021. With this recent permanent price level shock, it’s perfectly legitimate that 88 percent of voters in February said that “inflation” was still a big issue for them, of which 57 percent said food costs were their biggest concern. On the campaign trail, Harris and Trump are thus hearing angry voters say that inflation has been very painful.

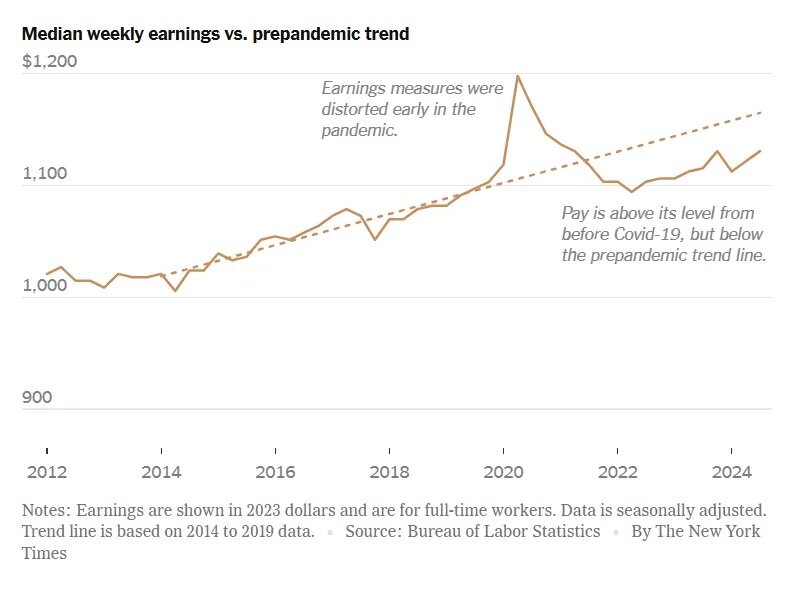

The public is right. Unexpected inflation really is painful for many households. First, in the short term, it cuts into real wages. While inflation should raise all prices proportionately, including wages, over time, workers’ pay is often locked in by contracts that only reset every year or so. An unexpected burst of inflation thus erodes real pay initially, not to mention inserting a high degree of uncertainty about where prices are going when workers renegotiate remuneration with employers next time. And real pay has struggled — it fell as inflation took off, and although it has recovered such that people are generally better off in real terms now than in 2019, the growth of median weekly earnings is still below its pre-pandemic trend (see New York Times chart below).

In fact, Harvard economist Stefanie Stancheva’s survey work shows that workers tend to think of their eventual catch-up cash pay increases as deserved for their performance, with the product price increases deemed a separate harmful affliction. High, unexpected inflation thus temporarily reduces real earnings, engenders worry and conflict for workers in wage negotiations, and leaves workers feeling like they’ve been shafted of real wage gains even after wages have “caught up.”

Second, given some prices are flexible and others stickier, unexpected inflation delivers arbitrary windfall losses and gains to different groups. Those on fixed pay rates, cash incomes, lenders, and businesses whose costs rise before they can raise prices tend to lose out from the “inflation tax”; workers with market power, fixed interest borrowers, and firms with long input contracts tend to benefit. Members of the public look around and see their relative positions changed by this wealth redistribution. It’s easy for losers to resent those seemingly “profiting” as they suffer – inflation feels inequitable and unpredictable. This is a key cause of demands for redress from the government — to “compensate me, to regulate him, to control x’s prices, and to tax y’s “excess profits”, etc” as the quotation from Axel Leijonhufvud at the start made clear.

Third, inflation creates inefficiency, because it incentivizes people to engage in time-consuming and costly behaviors to try to insulate themselves from its effects. Workers may engage in more conflict to protect their real pay—negotiating more frequently, joining unions, or even striking. Trump had half a point when he said the short-lived longshoremen’s strike was a reaction to inflation.

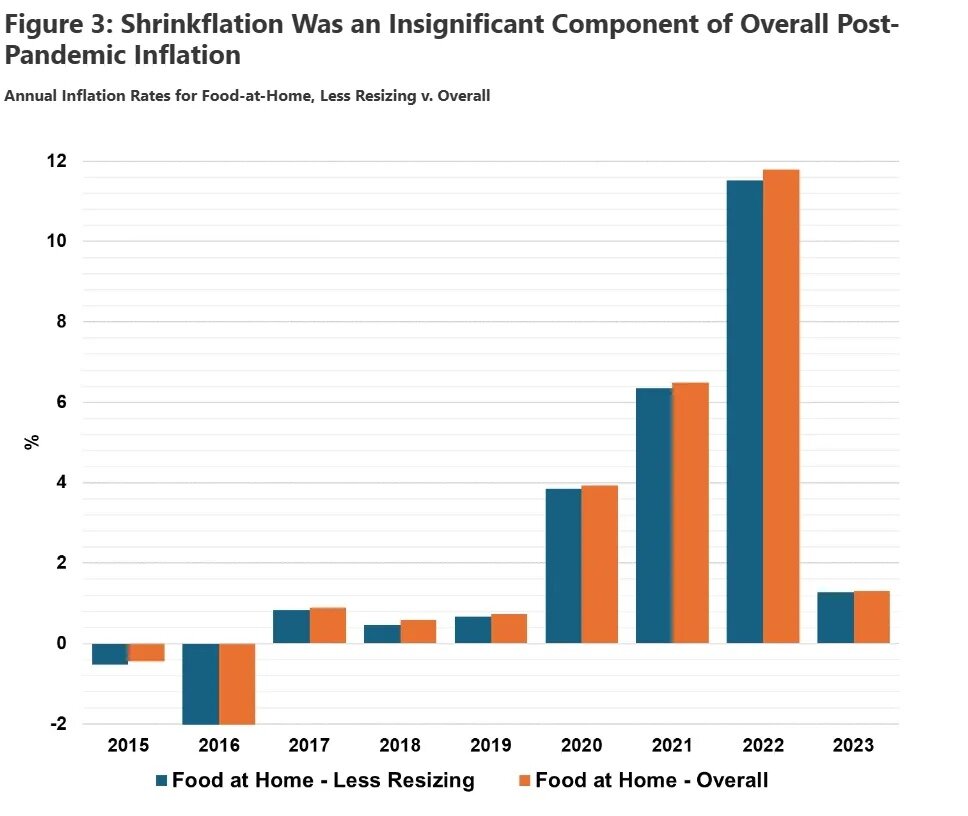

But it’s not just workers. High inflation means families must reassess their financial plans and rethink consumption patterns. Businesses must go through the costly internal decision-making processes of changing prices more often or even altering products to maintain custom (would customers prefer shrinkflation to a straight price increase, for example?)

Money illusion – the fact many people intuitively think in cash terms rather than “real” terms – means that, in making these adjustments to inflation, consumers and businesses make mistakes in their decisions. All this is occurring in a world in which relative prices between products are constantly changing with supply and demand shifts, meaning it’s not always obvious what’s “inflation” as opposed to a normal price movement for a product or input. High inflation thus makes economic decision making more difficult and, in general, more stressful.

And, finally, even when people recognize that we are living through a high inflation period, there’s mistakes made in forward-looking contracts from guessing how long the inflation will persist and at what level. Though we appear to have been spared this time, one macroeconomic risk is that workers, for example, will come to expect higher future inflation than that which the Federal Reserve delivers, so demanding higher cash pay. This can price workers out of jobs – creating unemployment. It’s why economists got so obsessed about inflation expectations remaining “anchored” when inflation was high.

All told, then, there are good reasons for the public to hate inflation, even though they might not fully understand all its economic consequences, let alone causes. Not only do the public find sharp price increases jarring, but they dislike their wages struggling to keep up, the arbitrary redistribution and conflict inflation brings, and the fact that inflation unmoors their whole sense of what reasonable prices and wages are.

Politicians, of course, know this. It is thus in their interest to deflect blame for inflation away from macroeconomic policymakers in Washington DC and towards other malevolent actors, whether Vladimir Putin for invading Ukraine, or else supposedly greedy corporations. And they have been helped in this effort by misguided public interventions in recent years from a raft of economists, commentators, and even businesses, who have propagated half-truths and misconceptions about the inflation to create an environment where mistaken understandings about its causes are widely held.

Confusing Micro for Macro: How Bad Inflation Analysis Encourages Bad Policy

Inflation, as economists understand it, is a general increase in prices across the economy—reflecting a decline in the value of a dollar unit of currency. This ultimately manifests itself as a proportionate increase in all prices across the economy. It occurs when there is an increase in the growth of money chasing goods relative to the growth of aggregate production, or else a fall in the growth of that output relative to the growth of money spending (a so-called negative supply-shock). The Federal Reserve seeks to keep inflation near target by affecting the money supply and interest rates to influence the money spending side of this see-saw.

Unfortunately, we can’t measure inflation directly, so we rely on price indices like the Consumer Price Index or the Personal Consumption Expenditures price index, which track weighted-average price changes for a “basket” of goods over time. There are well-acknowledged challenges of doing this: the basket of goods must be constantly updated as spending habits change, the quality of goods alter over time, and consumers substitute between products as relative prices fluctuate. At best, then, such indices are very imperfect measures of the macroeconomic inflation we are attempting to calculate.

One key downside of this method of estimating inflation is that it can lead commentators to become obsessed with what’s happening with sub-components of the index, like electricity prices, or rent, or used car prices. Any rapidly rising price is said to be “driving inflation,” as if its absence from the index would lower the calculated inflation rate. While that makes sense as a matter of basic math given these measures of inflation, it can mislead our understanding of inflation’s broader drivers as a macroeconomic phenomenon.

Consider housing rents. In the long-term, rents will go up by underlying inflation plus the price change of rents relative to other goods and services (i.e. the supply and demand conditions of the industry). It would make little logical sense then to look at large rent price increases and assume they have somehow been “driving” inflation – given they themselves are driven, in part, by inflation. Yet this is precisely how stories about inflation are framed. By leading commentators to think of inflation as an aggregation of what’s going on with individual prices, price indices encourage politicians to think “if only we implemented policies to reduce rent growth, then overall inflation would be lower.”

This is often an error. It applies microeconomic thinking to macroeconomic problems. Most policies to hold down rents would do nothing to change the fundamental macroeconomic balance of money growth or output growth. Hold down rents, and there’s more money left over for consumers to bid up other prices by spending more elsewhere. To a first approximation, overall inflation remains unchanged. Narratives that blame inflation on specific product prices—be it used car prices, or rents, or grocery bills—thus distract us from inflation’s true monetary causes. Obsessing over price index subcomponents is one reason why we hear misguided microeconomic “solutions” that fail to address the root causes of inflation—including targeted price controls.

It’s true that large supply shocks within individual markets—like some of the difficulties reopening after the pandemic and the gas price spike after Putin’s invasion of Ukraine—can and did make inflation worse in some periods over the last three years. Major negative supply-shocks undermine the economy’s ability to produce goods and services, lowering real output growth. Less real output for a given amount of money growth means an increased price level – i.e. temporarily higher inflation.

This was the theory that Federal Reserve chairman Jerome Powell had in mind when he first claimed that high inflation would be “transitory” in Fall 2021. The idea was that the spike in prices was driven by one-off factors – mainly post-pandemic supply chain issues — that would quickly dissipate, perhaps even fully reversing in short order. Inflation would thus rise and fall in a few months; the price level itself might even self-correct as supply chains unsnarled. Given the Federal Reserve couldn’t unclog ports or reallocate workers between sectors, but could only affect money spending—demand, through monetary conditions—tightening monetary policy was thought unnecessary and potentially harmful. The central bank just had to sit and wait.

Of course, inflation didn’t fall quickly. In fact, PCE inflation peaked at 7.2 percent in June 2022 and remains slightly above target today. Putin’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 and its impact on gas prices gave policymakers another “supply-shock” to help explain away inflation rising further. Yet while the war did raise the price level in 2022, it (just like pandemic supply chain issues) couldn’t explain the magnitude and persistence of the inflation we were seeing. In fact a huge spending boom powered by a mammoth growth in the money supply beforehand was pushing up prices across many sectors significantly even prior to Russian tanks rolling west.

Over time, with more prices adjusting, this reality became more obvious. Policymakers had been mistaking clogged ports and worker shortages as supply bottlenecks driving inflation, when those supply crunches mainly reflected huge increases in demand pushing capacity utilization to its limits. In short, monetary policymakers in DC mistook a demand driven inflation—too much spending—for supply problems they could do little about.

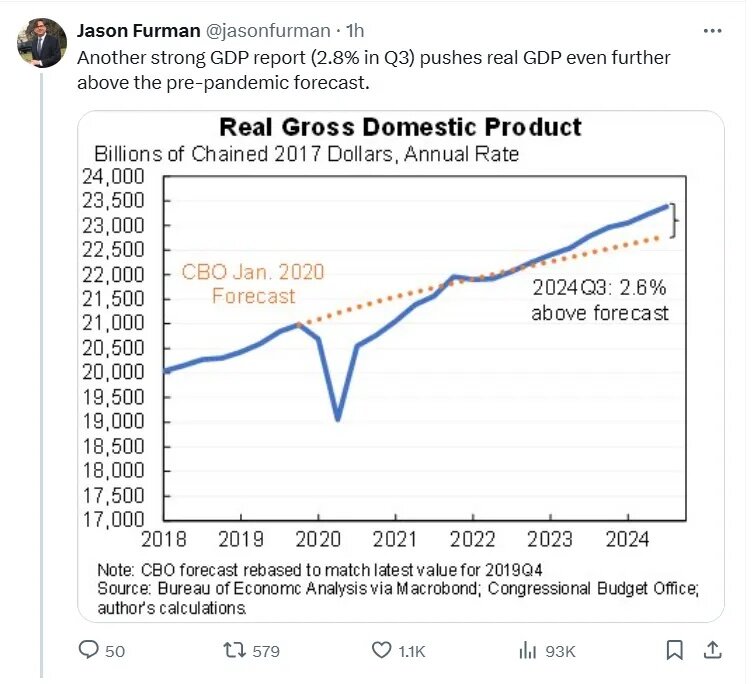

This is easy to see in retrospect, given now supply shocks have largely reversed. Consider the period from January 2021. The PCE price index today is 8.1 percent above where we might have expected it to have been had inflation remained at target throughout that period. How does this compare to trends in total spending on final goods and services (nominal GDP) and real output? Well, relative to if their 2010–2019 trends had continued, nominal GDP is currently 9 percent above where we’d have expected it to be. That indicates excessive total spending growth – a failure of macroeconomic policy. If inflation were all or mainly “supply-shocks” driving permanently higher prices, we might expect real output to be substantially below its pre-pandemic trend today. It is, slightly. But nowhere near the magnitude of the equivalent uplift in spending we’ve seen. In fact, real output is stronger than the Congressional Budget Office forecast in January 2020 (to take another metric, see below). That hardly suggests that unforeseen “supply shocks” are behind the unexpected permanent price level spike we’ve seen.

As Scott Sumner concluded in September, this headline data actually suggests all the excess price increases have now been driven by the “too much money being spent” side of the equation, rather than ongoing problems with the supply of goods.

How did policymakers, and many commentators, get this so wrong? The charitable take is that signs of a demand-driven inflation, driven by excess money growth, can sure look like “supply-shocks” in the short term. Demand and supply interact in setting prices. Excess demand quickly means production capacity limits get hit for many firms. Companies then feel as if shortages of labor and other inputs are their binding constraint. And they tell politicians and central bank surveys that it’s the inevitable cost-inflating effects of these supply-chain issues that cause them to raise prices.

Businesses are being earnest when they report this. The great economists Armen Alchian and William Allen provided an example, regaled by Milton Friedman, of how the role of excess money growth in driving inflation can get shrouded at the level of the individual firm. Suppose there’s a money-driven, widespread increase in demand for meat. The grocery stores and butchers see meat flying off the shelves and so order more from the wholesaler. The wholesaler runs out and so orders more from the packer. The packer starts running low and so instructs cattle buyers to purchase more animals. With increased demand and no near-term additional supply, animal purchase prices go up. Cattle buyers must then tell the packing houses they must pay a higher price. Packing houses tell wholesalers the same. The additional costs get passed down the line until, ultimately, the retail prices go up for consumers as all prices inflate.

Each actor in the chain feels as if they must raise prices because of their costs going up – supply issues – but the ultimate underlying cause was the additional demand from consumers having more money from overly expansionary macroeconomic policy. In real time, however, this can feel very much like a supply story.

Unfortunately, some economists and commentators muddy the waters even today by still insisting that the inflation spike was all a supply-shocks story. For some, it’s no doubt just politics: the idea that some combination of the Federal Reserve and Congress is to blame for high prices is an inconvenient truth for an incumbent administration during an election year. For others, such as Nobel prize winning economist Paul Krugman, it’s having a faulty macroeconomic model in mind.

Krugman’s recent writing homes in on why inflation fell again (PCE inflation is currently at 2.2 percent). He believes that if the explanation was demand being squeezed by monetary tightening, we’d have inevitably seen layoffs and unemployment rising, with real output struggling. Yet because the labor market has remained strong as inflation tumbled, he concludes that much of the disinflation we’ve seen must have been driven by positive supply-shocks. His takeaway? That a lot of the original inflation spike must therefore have been due to supply problems that have now reversed.

Yet the fall in inflation is perfectly consistent with monetary tightening that helped reduce spending growth in the economy. The annual growth rate of nominal GDP was almost 11 percent through 2021 but has fallen to 5.8 percent today. While positive supply-shocks might have aided disinflation, this large fall in spending growth would be expected to ease demand pressures too, and so long as expectations about inflation weren’t wildly inaccurate, this would lower inflation without creating widespread layoffs.

The pertinent point here, however, is that by emphasizing the “supply-shocks” story for inflation and disinflation, economists and commentators deflected attention away from macroeconomic policy. Doing so further encouraged policymakers to try to “fix” individual markets as a means of curing inflation.

This obsession with microeconomic theories for a macroeconomic inflation can be seen in another misguided narrative: “greedflation.” In sectors with flexible retail pricing but locked-in input costs—or where sellers anticipated rising future costs–companies raised prices before their input costs went up, delivering a temporarily higher profit margin. Others simply met higher demand levels by selling more, so increasing the level of profits by increasing sales. And in sectors where international supply shocks did hit, the higher market price did provide windfalls to domestic producers. As a result, our recent demand-fueled inflation coincided with rising corporate profits initially. Corporations and firms were thus soon accused of “price gouging” or profiteering. This was the origin of the speculative theories we’ve seen about “profit-led inflation.”

Democratic politicians, including Jim Himes, Sen. Elizabeth Warren, and Bob Casey, have pounced on the narrative that corporations’ pricing decisions have themselves driven inflation. Businesses, after all, decide their prices, don’t they? The most sophisticated greedflation story goes that companies used the undoubted cost-inflating supply-shocks of the pandemic and Ukraine to then jack up prices higher than “necessary” given these input price spikes. The fact that there were periods when overall corporate profit levels and inflation went up simultaneously was taken as slam dunk evidence of “profit-led inflation.”

Overall, subsequent studies have found that, in aggregate terms, rising mark-ups didn’t meaningfully occur, except for in a few sectors. Yet even for those industries, few greedflationists ask “why were businesses suddenly able to charge higher prices?” It’s not as if “corporate greed”, corporate concentration, or other indicators of market power suddenly surged. To believe that profit-seeking was driving inflation, one would therefore need to think that supply-shocks themselves created a shrouding opportunity for businesses to collude across many industries (nay, many countries) all at the same time. The chaos of cost-shocks, apparently, enabled oligopolies to form everywhere!

Does that seem likely as a matter of economics? Well, no. For starters, the argument doesn’t take competition seriously. Industries like grocery stores are competitive. If one chain was trying to gouge consumers, others would have a huge incentive to undercut them with lower prices and take their customers away. More crucially, it doesn’t take customers seriously. If buyers were being gouged, they’d have less left over to spend on other products, pushing their demand down and so forcing prices lower in other areas of the economy. An individual firm or even sector doesn’t have the power to raise overall inflation. The question is how consumers were able to pay higher prices in many industries at the same time. Might it be that there was excess money floating around to be spent to begin with — a failure of macroeconomic policy?

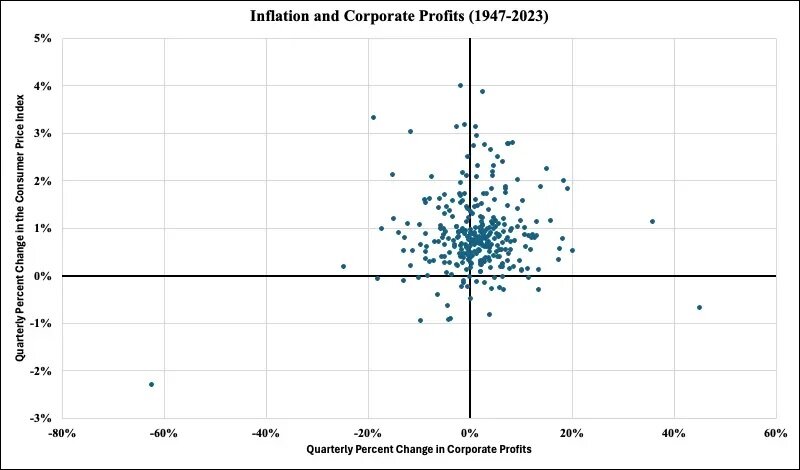

That is the explanation the “greedflationists” haven’t confronted: the only way that you get such a widespread increase in prices across so many sectors all at once is if there is an imbalance between money and output. This was exactly what some statistical analysis I undertook with economist Bryan Cutsinger showed for the post-war period. Corporate profit levels haven’t been well correlated with inflation over those decades — i.e. there’s no evidence profits drive inflation.

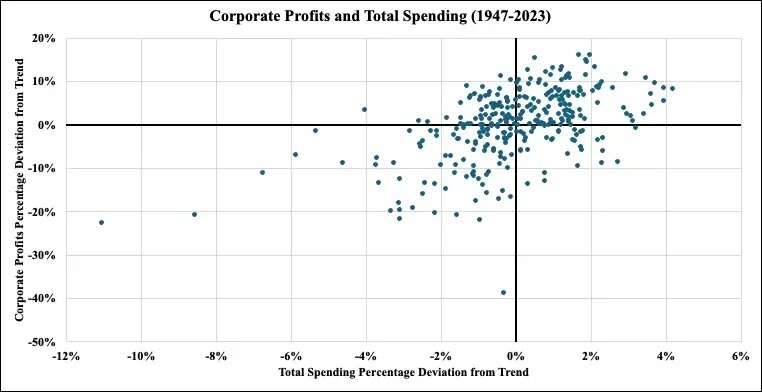

No, what is true is that deviations in total spending – nominal GDP – have been positively correlated with corporate profits. In other words, it’s more likely the story is the other way around: profits don’t drive inflation; but inflationary monetary policies driving higher money spending can temporarily drive profits higher.

Yet, five decades after inflation had last been this high, what was previously understood about inflation is no longer comprehended in Washington DC. The result has been a range of bad analyses about what caused the inflationary peak, the downstream effects of which have been awful policy proposals.

The Perfect Storm for Bad Policy

Let’s recap. High inflation brings a range of real economic harms and is hated by the public. It creates obvious winners and losers, encouraging demand for political redress. Given inflation’s macroeconomic roots, politicians and central bankers have incentives to play upon public ignorance by deflecting blame from fiscal and monetary policy towards other factors, like one-off supply issues in individual sectors, international gas price spikes, or even corporate greed.

Commentators and certain heterodox economists popularized all such views this time, the policy takeaway of which was that it was never necessary for the Federal Reserve to tighten monetary conditions to quell inflation, because it would either go away in time as supply chains unsnarled, or else could be ameliorated through more targeted microeconomic solutions. Such calls were only emboldened by the “long and variable lag” associated with the Federal Reserve’s pivot from wait-and-see to tightening, a delay that left the public feeling initially as if monetary policy was relatively powerless to control prices.

And so, this high inflation climate encouraged politicians to suggest microeconomic “solutions” to high inflation. The Biden administration, for example, sold its green energy subsidies, Lina Khan’s antitrust policies, government drug-price negotiations, and the administration’s anti-junk fee crusade as ways to get inflation down. Whatever their merits, all primarily affect relative prices between goods and services, rather than the aggregate price level. To a first approximation, they do nothing to quell inflation.

Worse, but perhaps unsurprisingly, this intellectual environment helped rekindle the allure of price controls. After all, if inflation merely reflects just a bunch of individual prices being higher, some of which are due to greed or corporate power, then why shouldn’t the federal government use its authority to hold prices down?

Mercifully, we didn’t adopt economy-wide price controls like those seen during World War II or under Richard Nixon this time. There is enough academic knowledge out there and appreciation of history to know, perhaps, that freezing or restraining prices across the economy not only creates shortages, black markets, and inefficiency, but merely suppresses measures of inflation from reflecting the realities of underlying monetary forces.

Nevertheless, a range of more specific price cap proposals were advocated after inflation took off. Elizabeth Warren cobbled together a federal anti-price gouging law proposal, for example, that would have given the Federal Trade Commission vast new powers to prevent “excessive” price rises after “exceptional market shocks.” This would have meant effective price caps across vast swathes of the economy that experienced demand spikes during the pandemic. Rent control proposals took off in a range of states, with many left-wing groups calling for a federal rent control regulation. The Biden administration talked up how companies’ “junk fees” were costing Americans billions of dollars, implying certain pricing practices were raising net prices, rather than just changing their structure.

This drumbeat of faulty analysis and policy advocacy seeped into public opinion. A YouGov poll taken in June 2023 asked Americans what or who they blamed for inflation. The top answer was “large corporations seeking maximum profits,” although general discontent with the Biden administration’s spending, particularly among Republican voters, was a common answer too. Strikingly, despite the extensive coverage of the Fed’s responsibility for monetary policy, YouGov hadn’t even included the central bank as a prompted answer for who or what was responsible.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, given that so many people were convinced that inflation was a result of supply-shocks or malevolent businesses, when asked what policies would help reduce inflation, the top public answers were increasing domestic oil production, strengthening supply chains, and the government imposing restrictions on price increases.

The Biden administration saw both a weakness and an opportunity in these public opinion polls. Even as measured inflation fell, the elevated cost of living remained a live political issue. Recognizing that high prices resulting from the previous high inflation were an albatross around his neck for re-election, President Joe Biden began the year by throwing as much blame for inflation corporations’ way as possible. His State of the Union address bemoaned “price gouging,” profit padding, and “shrinkflation.”

The latter, of course, was just a manifestation of inflation, which my own research shows barely altered the volatility of prices (see chart below). The other claims mistook the symptoms of inflation for its cause. But at this stage the facts didn’t matter. “Greedflation” was firmly entrenched as part of the mainstream Democratic economic narrative. As polls and studies crystallized that the major areas of concern for the public were grocery bills, rents, and the cost of financing major purchases like homes and cars, it was perhaps inevitable that we’d see populist policies adopted to show politicians cared.

That is how we reached the current mess of presidential election policy proposals. Harris has promised the first ever federal anti-price gouging law, applied to groceries. Some commentators have downplayed the significance of this proposal, equating it to state level anti-price gouging statutes that only apply in very limited circumstances and that spare companies that can prove their costs have gone up. Yet Harris herself is running ads saying such laws will help to lower food bills – i.e. suggesting this will create binding caps on prices. And the obvious implication of her proposal is that she thinks such laws could have been invoked over recent years to dampen inflation, despite no obvious emergency after the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic.

In any case, economists oppose anti-price gouging laws, even at the state level, for entrenching shortages and creating an inefficient allocation of goods during and after weather emergencies, especially when demand spikes. A federal version could function as de facto price controls on groceries or create legal uncertainty about what retailers and wholesalers can charge in an inflationary environment, creating a recipe for excess demand, black markets, and mangled supply chains. And all based on a faulty premise: a recent survey of top economists for the Kent Clark survey group revealed that 77 percent of those polled think that there’s little evidence grocery price gouging was driving higher food prices (0 percent agreed).

If Harris’s views on grocery price gouging are disliked by economists, her stance on rent control is loathed. The Vice President has continued with President Biden’s policy proposal to cap rent increases for “corporate landlords” at 5 percent per year. Rent control is probably the best studied price control in economics. A recent meta-analysis summarized the literature, showing that holding rent prices below market rates, while lowering prices for affected units, raises rent for non-controlled properties, reduces the supply and quality of rentable accommodation, misallocates properties, and reduces tenant mobility. Weighted by their confidence, almost three-quarters of economists in one poll said that the policy would “substantially reduce the amount of apartments available for rent.”

Not content with these two price control policies, Harris has also promised to continue President Biden’s misguided war on “junk fees.” In reality, that means further arbitrary price controls across a range of sectors, from airlines to credit cards, and cable providers to hotels.

Remarkably, despite acknowledging the flaws of Harris’s own ideas, former President Trump has managed to put together a package of policies that many economists think will be even worse for the economy, or at least worse for inflation.

His headline proposals are for a universal tariff of 10 or 20 percent on all imports and at least 60 percent tariffs on all Chinese goods. Tariffs, of course, reduce real output – they are like a negative supply-shock to the economy. That means that unless the Fed meets them by also squeezing demand through monetary tightening, they will also lead to a one-off increase in the price level, temporarily increasing inflation. While this wouldn’t drive ongoing inflation as economists understand it, it would raise the cost of living and reduce competitive pressures on U.S. industry. In fact, weighted by confidence, 96 percent of economists in one recent survey said that this would increase prices for Americans.

A similar story applies to Trump’s threat of mass deportations of illegal immigrants, many of whom work in agriculture. Although we wouldn’t expect this to affect medium-term inflation, such a policy would increase the price of many foodstuffs, or else reduce the products’ availability entirely. That’s hardly what families struggling with grocery bills want to hear.

When it comes to macroeconomic policy, Trump has promised a raft of targeted, large tax cuts – No Tax on Tips/Overtime/Social Security, for example — that will eat into the base of federal revenue, without offsetting promises to cut spending. The result? More borrowing and more debt. Although that need not necessarily cause inflation – the correlation between budget deficits and inflation is low – it will merely accelerate the path to fiscal insolvency, which in a country with its own currency likely means debt monetization and so potentially much higher inflation in future.

More pertinently, Trump has mused many times that he wants a greater role for the President in setting interest rates. All monetary policy is political, but history suggests that such overt politicization is a sure route to creating a political business cycle ‑i.e. stimulus near elections — and, on average, higher, not lower, inflation. Indeed, Trump spent much of his last term urging Fed chair Jay Powell to loosen the monetary strictures. Little surprise, then, that 93 percent of economists in one recent survey said such a change would worsen monetary policy outcomes.

And, now, of course, Trump is proposing a price control of his own – on credit card interest rates. “While working Americans catch up, we’re going to put a temporary cap on credit-card interest rates,” he told a New York rally. “We’re going to cap it at around 10%. We can’t let them make 25 and 30%.” As Nick Anthony explains in The War on Prices, the main result we should expect of that is less credit offered to the highest risk borrowers.

Where economics is concerned, then, this election is one shaped by inflation and the political and social reaction to it. Voters concerned about their living costs are left with a rather depressing choice. Harris has channeled voter frustration by gaslighting the public into blaming companies for high inflation and threatening price controls to counteract businesses’ supposed malfeasance. President Trump’s platform would squeeze the supply-side of the economy through trade restrictions and deportations, while promising even more reckless macroeconomic policies.

An inflation driven by too much macroeconomic stimulus has thus spawned a political dynamic hastening us down the road to price controls and other damaging interventions. This reaction, although not unsurprising, is an underappreciated cost of price volatility and macroeconomic mismanagement. But these are costs that we may nevertheless all pay for, whoever wins next Tuesday. And they are the product of mixing the public’s aversion to inflation, with politicians’ incentives, and the intellectual errors we’ve seen in interpreting the inflation we’ve just lived through.

For more on these themes, you can buy The War on Prices.