We found the following tweet from Paul Krugman jarring:

Gotta say it: the original Team Transitory proposition was that inflation would subside without the need for a big rise in unemployment. Not looking so wrong now (supercore is core ex used cars and shelter, 6m annualized) 1/ pic.twitter.com/ma2pQdtm2i

— Paul Krugman (@paulkrugman) July 12, 2023

Krugman was writing following news that the headline U.S. annual rate of consumer price index inflation rate had fallen to 3.1 percent. Coupled with other tweets, he seemed to be implying that this trend, paired with unemployment remaining low, vindicated those who in 2021 said we shouldn’t panic much about inflation, because it was a strictly temporary phenomenon that would soon fall away anyway.

Really? That’s not what I remember the argument of “Team Transitory” at the time to be. Admittedly, the term itself was never precisely defined and there was no official statement that set out a prediction. But there was a clear economic argument deployed by the people who embraced the “transitory” term, including the Fed chair Jay Powell. And the way they were talking implied that inflation would subside over months, not years.

That’s because the original Team Transitory in 2021 saw inflation as a result of bottlenecks and supply-shocks arising as the economy reopened from lockdowns. In other words, it wasn’t that there was too much aggregate demand triggered by monetary and fiscal stimulus; the issue was that demand had returned to normal levels following reopening, but that supply couldn’t keep up, driving up prices. Once those bottlenecks partially unwound themselves, they thought inflationary pressure would dissipate (and maybe prices would even fall back down again, if the supply-shocks completely unwound). The policy implication was that the Fed tightening monetary policy to choke off inflationary pressure would be unnecessary and damaging.

A lot of people disagreed with this view, of course, and so got dubbed “Team Permanent.” This was always a misleading name, because nobody was arguing that inflation would be entrenched at high levels for decades. No, Team Permanent was really “Team Persistent.” They thought a large component of inflation was being produced by excessively loose monetary conditions and/or soaring government spending, goosing aggregate demand. This would lead to a broader-based inflation than one contained in sectors affected by the pandemic, over a longer period of time, and would manifest in rising cash wages too. In order to get inflation back down, Team Permanent therefore advocated for tighter monetary conditions to reduce economy-wide spending growth.

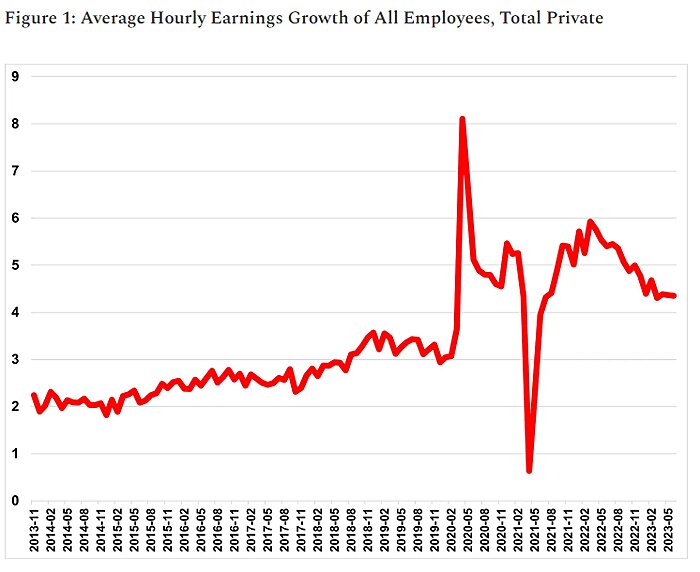

We know what happened next: inflation did persist. And as Figure 1 shows, we have also seen a period in which cash wage growth has been much higher than the pre-pandemic trend too (though not by as much as the elevation of prices, hence real earnings have fallen since inflation took off).

While, yes, it’s true that supply-shocks from the Ukraine war and the pandemic have raised the price level, the basic facts of above-trend nominal spending and a much broader inflation than one limited to sectors affected by the pandemic suggests Team Persistent were overwhelmingly correct in their analysis.

That’s why Krugman’s tweet baffled us. Were we misremembering the nature of the debate and what it meant to be “Team Transitory” all along?

Looking back on what people actually said in 2021, it doesn’t seem so:

-

In May 2021, Krugman himself told Business Insider “I’m on the transitory side, although not with high certainty,” later implying that he expected high inflation for a time because of the high prices associated with post-pandemic bottlenecks.

-

In June 2021, Fed chair Jerome Powell told Congress: “Inflation has increased notably in recent months. This reflects, in part, the very low readings from early in the pandemic falling out of the calculation; the pass-through of past increases in oil prices to consumer energy prices; the rebound in spending as the economy continues to reopen; and the exacerbating factor of supply bottlenecks, which have limited how quickly production in some sectors can respond in the near term. As these transitory supply effects abate, inflation is expected to drop back toward our longer-run goal.” These factors, he said, “don’t speak to a broadly tight economy — the kind of thing that has led to high inflation over time.”

-

New York Federal Reserve Bank President John Williams agreed that inflation was transitory, saying “I expect that as price reversals and short-run imbalances from the economy reopening play out, inflation will come down from around 3% this year to close to 2% next year and in 2023.”

-

In August 2021, the Economic Policy Institute’s Josh Bivens and Stuart A. Thompson asserted in the New York Times that a “base effect” and supply chain problems were responsible for inflation in several COVID-sensitive sectors. “For now, inflation is well contained and the Fed should monitor it closely,” they concluded, “but not act rashly. Cheaper furniture, fast food, used cars and airfares would be nice, but they aren’t worth cutting the economic recovery short.”

-

By September 2021, Krugman hedged a bit by redefining “transitory” as inflation not creating embedded higher inflation expectations. He said he still saw little evidence of this, and that a “super core” measure of inflation that excluded volatile prices associated with food, energy, and pandemic-related sectors still wasn’t taking off.

-

A tweet from Krugman in October 2021 then claimed a swift victory for Team Transitory as core inflation seemed to be falling:

Three month core inflation. Why isn’t everyone calling this a win for team transitory? pic.twitter.com/KB9EawJLo1

— Paul Krugman (@paulkrugman) October 13, 2021

-

By November, Krugman admitted inflation had been stronger than he’d expected, starting to talk instead of inflation being elevated for well over a year. Still, he erred on the side of being concerned the Fed would do too much in tightening policy.

-

Towards the end of the month, Fed chair Jay Powell said that “it’s probably a good time to retire that [“transitory”] word” considering that inflation was proving more powerful and persistent than expected. He opened up the possibility for redefining the debate too, saying: “The word ‘transitory’ has different meanings to different people…We tend to use it to mean that it won’t leave a permanent mark in the form of higher inflation.” But he was still really blaming supply-shocks for inflation then.

-

By December, Krugman wrote: “Even once the inflation numbers shot up, many economists — myself included — argued that the surge was likely to prove transitory. But at the very least it’s now clear that “transitory” inflation will last longer than most of us on that team expected.”

-

Alan Blinder acknowledged in the Wall Street Journal that Team Transitory had been caught by surprise by the strength of inflation. But while he thought it might now last for longer than expected, he still said he was in Team Transitory, linking inflation’s path to bottlenecks that would eventually sort themselves out.

-

By January 2022, however, when it became clear inflation was broader-based, Krugman admitted:

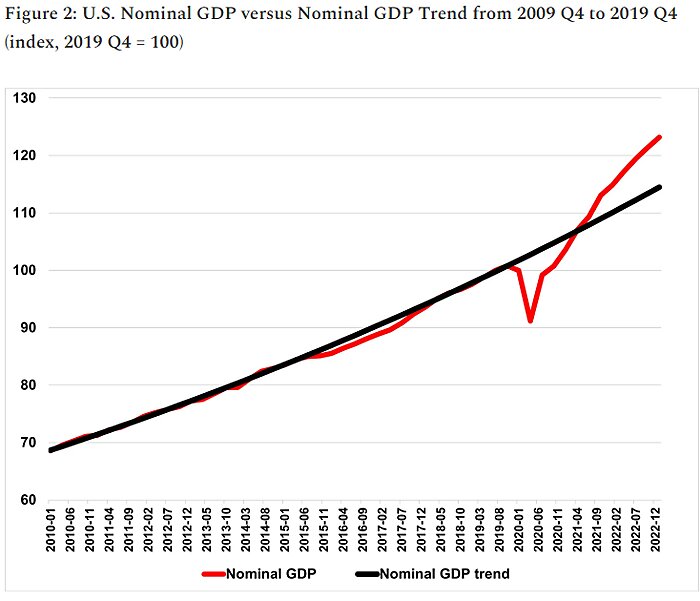

Now, it’s to Krugman’s credit that he admitted this so early, because since then it has become undeniable that there was a large demand-side component to inflation too. David Beckworth regularly publishes a version of Figure 2 below that shows how the level of nominal GDP soared above its pre-pandemic trend from mid-2021. This highlights that, even if you think the Fed shouldn’t have done anything to offset the effects of supply-shocks on the price level, the U.S. would still have experienced significant additional inflation because of too much spending.

Why would Krugman suggest otherwise now?

Well, reading his newsletter later last week, it is obvious that Krugman was conflating two different debates: the “is inflation transitory or persistent?” debate of 2021 with the more contentious disagreement among Keynesians over whether efforts to bring down inflation required risking substantially higher unemployment.

Economists such as Larry Summers, who called inflation’s persistence correctly, looked at macroeconomic history and thought that the necessary monetary tightening would likely bring substantive collateral damage to employment. Others thought a “soft landing” possible, at least if the Fed didn’t act too aggressively, precisely because they still thought inflation was driven mainly by supply-shocks. Lots of those who thought inflation was transitory were the same folks who believed a soft landing was possible, and there was substantive overlap between Team Permanent and those who judged a hard landing likelier. Krugman thus wants to relitigate the whole period.

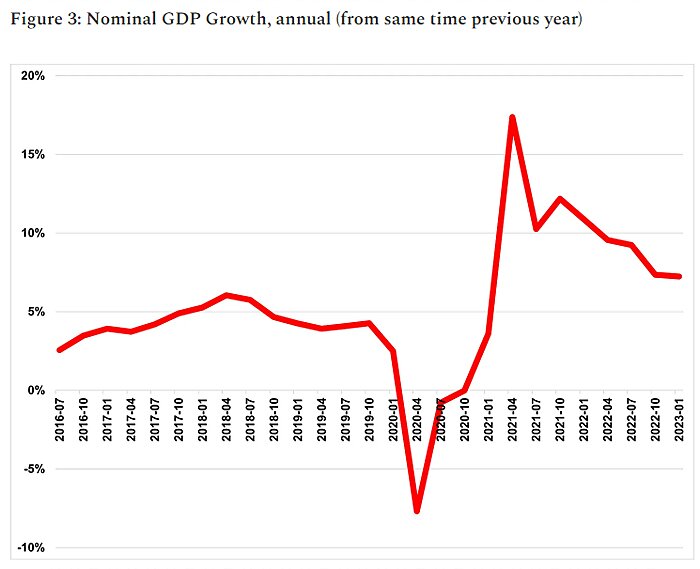

Personally, I don’t agree with either side of this intra-Keynesian debate, because they obsess too much on unemployment as a guide. As Figure 3 shows, the growth rate of nominal spending has already fallen significantly as monetary conditions tightened. Reducing the growth rate of spending from very high levels helps deliver disinflation, and need not reduce employment much even in the short-term.

As you can see, however, nominal GDP growth is still a bit higher than the pre-pandemic trend. It would be hard to hit the Fed’s inflation target if this continued, which is why some people argue for tightening policy further. But the money supply growth (M2) has actually been negative since the back end of last year. Given this tends to affect nominal spending levels with a lag, it implies that there is a real risk of the Fed having already overtightened too much, in which case it may well be that Krugman is being premature in celebrating a soft landing and that a recession occurs in the very near future.

All this discussion, however, is really besides the point. None of it affects the evaluation of the 2021 debate over whether rising inflation was purely a supply-side phenomenon that would quickly unwind. Many very important people, declaring themselves “Team Transitory,” believed this to be true. And the evidence suggests they were wrong. That their predictions of outcomes in later phases of this crisis are (so far) closer to the outturns we’ve seen is irrelevant.

Other Links:

-

My Cato review of Stephen King’s excellent book We Need To Talk About Inflation.

-

Remember the “pink tax” — the furore over “sexist” pricing of clothes, toys and toiletries? Such claims were greeted with great fanfare 5–6 years ago, just like today’s “greedflation” narrative. I wrote my Times column last week on how new economic research is debunking the idea that companies discriminate on price by gender. Predictably, there’s been little media follow-up to these developments, despite the mass reporting of the initial narrative. One suspects the same will eventually occur with the tale of “greedflation.”

-

Speaking of which, I thought this was an excellent piece by Josh Hendrickson on greedflation: