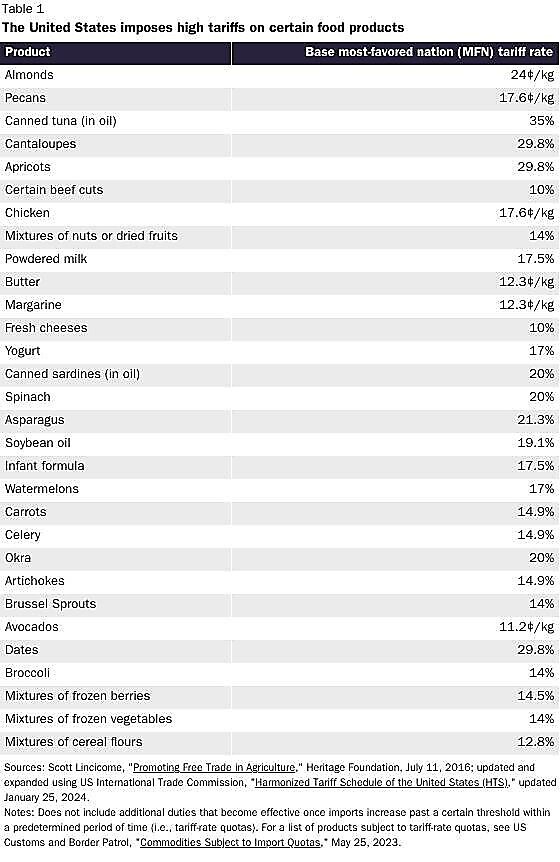

Now, in the grand scheme of things, these tariffs have a relatively small impact on households’ overall dollar grocery bills. The point is: politicians knowingly make essentials like food more expensive than they need to be under a free trade policy. And Democrats are certainly correct that some of Donald Trump’s policies would raise grocery prices further.

Trump has suggested he would introduce a new 10 percent global tariff on imports from non-FTA countries and 60 percent tariffs on Chinese goods. This would raise grocery prices further through two mechanisms. First, at least part (and evidence suggests the lion’s share) of any tariff increase on specific foodstuffs would be passed on directly into higher consumer prices borne by Americans. Food would become more expensive to import and there would be less competitive pressure on domestic substitutes, increasing domestic prices too. Second, domestically produced food would also see price hikes due to increased costs for certain imported inputs to food production. For example, any imported packaging materials, fertilizers, mechanical tools or more would jump in price if subject to the tariffs, increasing overall production costs for domestic farmers or manufacturers.

The magnitude of the total impact on grocery bills after producers substitute to alternatives is an open question. But the direction of the price effect from this inefficiency is not. And this price uplift is compounded by the fact that Trump is promising mass deportations of illegal migrants. The Center for Migration Studies has estimated that 45 percent of agricultural workers in the United States are undocumented migrants. Across the country as a whole (and in 22 states), “farming” is the occupation with the highest proportion of illegal migrant workers. If Trump could deliver a successful deportation program of many of these workers (and it’s a big if), this major negative labor supply-shock would raise overall food prices higher still, with much larger price increases for the most labor-intensive foodstuffs.

Why? Well, because although the evidence suggests low-skilled migrant flows don’t have hugely depressive effects on domestic wages, nobody denies demand curves for labor remain downward sloping. A fall in the supply of workers would thus still modestly increase agricultural wage rates, raising farmers’ costs of production.

Where farm owners are able to, the higher price of labor will encourage them to substitute away somewhat from labor-intensive food production to more capital-intensive crops or production techniques, as happened after the end of the bracero migrant worker visa program in the 1960s. For foods which see an increased supply from this substitution effect, prices might actually fall. But for other goods that require physical human picking or treatment, like many fruits and vegetables, prices will rise, reflective of the somewhat higher wages of the relevant workers and the fact that for some produce it will just become uneconomic to farm it. And given that, overall, the deportations would encourage farmers to pursue investments and crop production that would be inefficient without the removals of these migrants, overall food prices would go up somewhat.

Democrats therefore have a point that Trump’s policies on trade and immigration risk higher food prices. Of course, as I’ve written before, Team Trump’s mooted proposal to compromise the Federal Reserve’s independence and its interest in continuing to run unsustainable budget deficits risks higher inflation as well (a rise in the general level of all prices). On the flip side, we could go through a similar exercise with Democratic macroeconomic and microeconomic policies — where I’m sure the latter would push up the relative price of energy compared to Trump’s agenda.

The point is that these types of policies (while damaging) are distinct from attempting to directly control market prices, which, as our book documents, has a terrible record of failure: creating shortages, black markets, and deteriorations in quality.