President Trump is preparing to declare the opioid crisis a “national emergency” next week. Yet policymakers should be careful about the measures they take to address this issue.

For years now, federal and state authorities have focused on the supply side of the problem, targeting prescription-drug producers and providers. This has been the media’s focus as well: 60 Minutes ran a story October 15 delving into the Drug Enforcement Administration’s efforts to stem supply, for example. But new information suggests that this approach is driving opioid abusers away from illegally obtained prescription opioids and towards heroin, fentanyl, and mixtures of the two. And this is increasing the death rate from drug abuse.

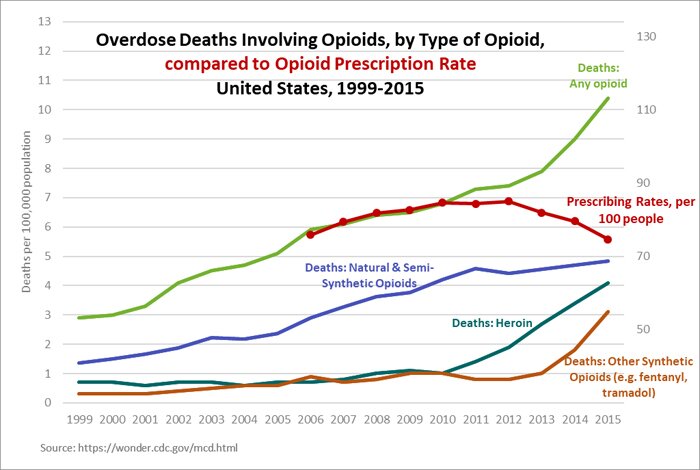

Nonmedical use of prescription opioids peaked in 2012, according to the National Survey on Drug Use and Health, and total opioid use was lower in 2014 than 2012. Health-care practitioners have steadily curtailed the prescribing of opioids since 2010, the production of prescription opioids has come down under the direction of the DEA, and the federal government has encouraged pharmaceutical manufacturers to develop "abuse-deterrent" formulations of prescription opioid pills, meaning the drugs cannot be modified for injecting or snorting. All 50 states have prescription-drug-monitoring programs aimed at curtailing doctors' prescribing habits and intercepting patients who "doctor-shop."

Yet the opioid-overdose death rate continues to rise. Such deaths reached an all-time high of 33,000 in 2015, and according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention the numbers for 2016 will be even worse.

Meanwhile, the drugs causing these deaths are changing. In 2015, the majority of opioid-overdose deaths were from heroin (often laced with fentanyl) — not prescription pills as had been the case in the epidemic's early years — and deaths from fentanyl alone doubled over the previous year.

The supply-side approach is based on the belief that the cause of the problem is doctors' prescribing opioids for patients in pain who then become addicted. Evidence suggests this is a misdiagnosis. The overwhelming majority of opioid-overdose victims are not patients receiving pain medicine; instead, they are mostly individuals with risk factors such as unemployment or childhood trauma. Only a minority of abusers even obtain prescriptions, according to the NSDUH.

Numerous studies have linked abuse-deterrent formulations of opioid pills with the migration of abusers to heroin. Researchers at Notre Dame University reported in a June 2017 working paper that they found a "one to one substitution of heroin deaths for opioid deaths" after the original formulation of Oxycontin was replaced with an abuse-deterrent one in 2010. And far from helping, states' monitoring programs seem to be contributing to "significantly higher mortality rates in legal narcotics, illicit drugs, and other and unspecified drugs," according to a May 2017 study.

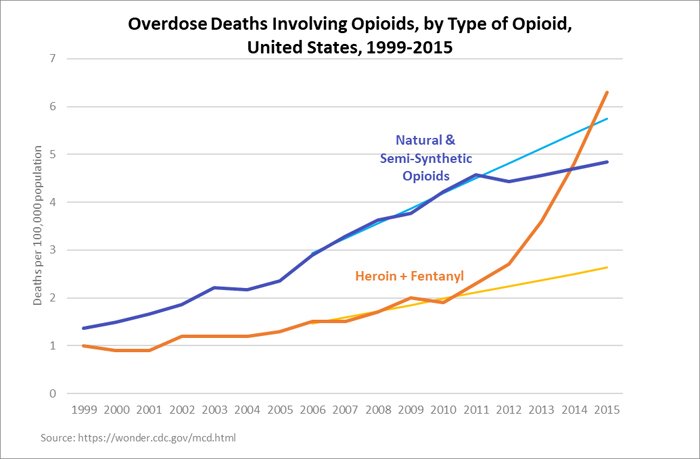

Recently, Mississippi state representative Joel Bomgar, working with data supplied by the CDC, tracked the overdose-death rates for prescription opioids, heroin, and fentanyl from the years 2006 to 2015 (the most recent year available). He noted that the five-year trend line from 2006 to 2010 predicted overdose deaths from prescription opioids of 5.75 per 100,000 in 2015, but between 2010 (when vigorous supply-side interventions were implemented) and 2015 the actual rate went to 4.84 per 100,000. On the other hand, the pre-2010 trend predicted an overdose rate of 2.62 per 100,000 for heroin and fentanyl in 2015, but the actual overdose rate rose to 6.30 per 100,000. This implies that about one fewer person per 100,000 is dying from prescription-opioid overdose five years after restrictive policies went into effect, in exchange for nearly four more people per 100,000 dying from heroin and fentanyl.

Bomgar also found that the opioid-overdose rate as a proportion of opioid prescriptions was very stable, at roughly one overdose death per 13,000 prescriptions, from 2006 to 2010. But after 2010, a reduction in prescriptions corresponded with increased overdoses. As the prescription rate decreases, patients get cut off from pain medications, and some, in desperation, seek relief in the illegal market. Also, the pool of prescription opioids available in that market is diminishing, and the market is flooded with cheap and easy-to-obtain heroin and fentanyl. In many cases drug dealers insert fentanyl into counterfeit oxycodone capsules for sale as well.

Something is clearly driving people to heroin, fentanyl, and fentanyl-laced opioids. A report in the November 2017 journal Addictive Behaviors notes that, among opioid users seeking treatment since 2010, just 8.7 percent of those who'd started their opioid abuse in 2005 had begun with heroin. Of those who'd started in 2015, one-third had. In other words, an increasing share of opioid addicts don't even get their start with prescription pills, even as many pill users are switching to heroin. Doctors are clearly not to blame for these shifts.

Too many overdose deaths result from the proliferation of dangerous, impure, and fentanyl-laced drugs driven by the economic incentives that always accompany drug prohibition. When a strategy makes things worse year after year, we must change course.

Allow doctors to use their best judgment to treat patients in pain. Direct resources away from current restrictive measures, and instead towards medication-assisted treatment, needle-exchange programs, expanded access to the overdose antidote naloxone, and other forms of harm reduction. It's time to recognize that current opioid policy is contributing to the overdose crisis.