For years, North Korea has been crushed by a communist command economy, producing little besides mass starvation. More recently, the plight of North Korea’s economy has been exacerbated by harsh, foreign economic sanctions — which only seem to have driven the regime to double down on its nuclear ambitions.

Following North Korean supreme leader Kim Jong-il's death in December 2011, many around the world had high hopes that his successor (and son), Kim Jong-un, would launch economic and political reforms. Unfortunately, in the year and a half since he assumed power, the new supreme leader has not delivered on his advertised economic reforms,and misery continues to grip all but those in North Korea's communist ruling class.During the past few months, North Korea has been the subject of out sized news coverage. The recent pea cocking by the Supreme Leader — from domestic martial law policies to tests of the country's nuclear weapons capabilities — has successfully distracted the media from North Korea's economic woes.

Indeed, behind the saber-rattling, the missile tests, and the basketball games with Dennis Rodman, is an economic story— one with important geopolitical implications, not only for North Korea, but also for China.

North Korea's Hyperinflation

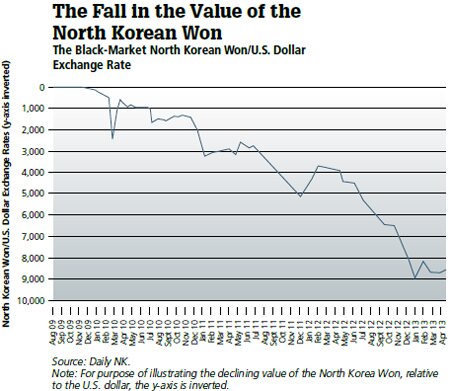

For years, North Korea's currency, the won, has been officially pegged to the U.S. dollar. That said, exchange controls and a plethora of associated regulations and harsh penalties have rendered the won in convertible. This, of course, has given rise to a healthy black market for foreign currency. North Korea's monetary dysfunction has been accompanied by severe inflation problems.

In 2009, the North Korean government attempted to address these problems by implementing a phony currency"reform" program, which it promptly bungled. The so-called reform was actually just a currency redenomination program,which arbitrarily lopped two zeros off every won note. North Koreans were given less than two weeks to exchange all of their won for new notes. And, the government set limits on the quantity of old won a family could exchange for new won.For those North Koreans who had saved a few too many won,the redenomination program was effectively a wealth tax program,too.

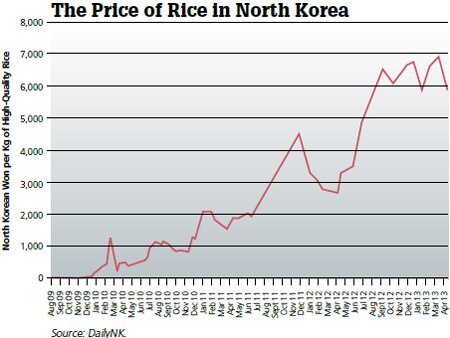

It should come as little surprise that Pyongyang's bungled currency reform sparked a panic in North Korea's primitive,underground markets for goods and services. The price of rice, for example, promptly skyrocketed during this period (see the accompanying chart).

These markets, which developed out of necessity during the famine of the 1990s, primarily exist to counteract shortages that result from state control of agriculture. Indeed, the United Nations has estimated that 50% of the calories consumed by North Koreans come from food purchased in these underground markets.

To gauge the inflation temperature in cases such as North Korea's, we must obtain black-market exchange-rate data. Black-market exchange rate data for the won are collected by Daily NK, a Seoul-based news service. With the bungled currency reform, the demand for hard currency accelerated, as more and more merchants in the underground markets required transactions to be conducted in hard currency. In consequence, the value of the won plummeted on the black market (see the accompanying chart).

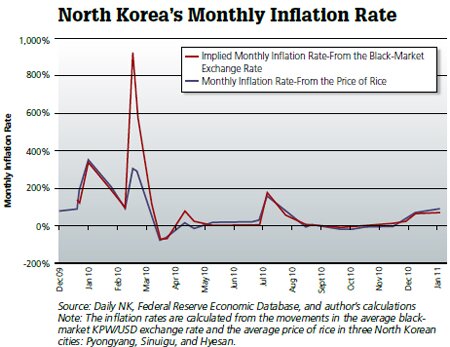

So, what happened to the overall price level in North Korea in the wake of the currency reform? Well, black-market exchange rate data allow us to reach a reliable estimate of North Korea's inflation rate. As the accompanying chart shows, the 2009 panic sparked an inflation surge in North Korea.

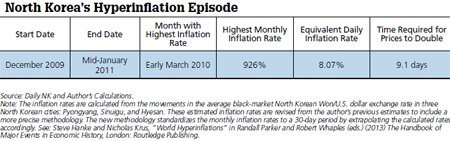

As the chart illustrates, the inflation rate implied by the change in the black-market exchange rate proves quite accurate, as it tracks closely with the inflation rate implied by changes in the price of rice. Thus, we can conclude that the inflation crisis that began in 2009 quickly accelerated into hyperinflation, which occurs when the monthly inflation rate exceeds 50%. It was not until mid-January 2011 that North Korea's hyperinflation episode finally came to an end (see the accompanying table).

During the hyperinflation period, many North Korean consumers began to exchange their ever-depreciating won for more stable foreign currencies, such as the Chinese yuan and the U.S. dollar, in a desperate attempt to preserve their wealth and purchasing power. Although North Korea is no longer experiencing hyperinflation, elevated rates of inflation continue to plague the country's economy. Indeed, I estimate that North Korea experienced an annual inflation rate of 116% in 2012. As a result, the won's popularity continues to decline.

North Korea's "Dollarization"

It is not surprising, therefore, that the Chinese yuan and U.S. dollar are now being used more widely in North Korea than the won. According to Daily NK, North Korean markets along the Chinese border now conduct approximately 80% of their transactions in Chinese yuan. Markets farther from the border are said to conduct approximately 50% of their transactions in U.S. dollars.

This confirms that North Korea is experiencing a phenomenon that goes hand-in-glove with elevated inflation — "spontaneous dollarization." This phenomenon of voluntarily dumping the domestic currency in favor of a stable foreign currency (not necessarily the U.S. dollar), has been widespread in recent years, despite the fact that Pyongyang has criminalized the circulation of foreign currencies on the black market.

After years of runaway inflation, many have simply lost faith in the North Korean currency. North Korean workers involved in trade with China typically request their pay in Chinese yuan. And, when a foreign currency isn't available, a commodity will do. One of the more curious examples of this can be found in the Kaesong Industrial Complex, which until recently was jointly operated by North and South Korea. For a time, workers used a South Korean marshmallow cookie treat, the ChocoPie, as sort of unofficial currency within the complex. The dollar "exchange rate" for a ChocoPie (which costs about 25 cents in South Korea) reached nearly $10 in Kaesong before management ceased giving workers their bonuses in ChocoPies. This should be "déjà vu all over again" for anyone who has read R.A. Radford's 1945 classic, "The Economic Organisation of a P.O.W. Camp."

So, the North Koreans are proceeding down the path to dollarization, as people often have in other inflation-ravaged countries, such as Zimbabwe. In mid-November 2008, Zimbabwe's hyperinflation reached an annual rate of 89.7 sextillion percent — that's roughly 9 followed by 22 zeros. Finally, after over a year and a half of hyperinflation, the people of Zimbabwe simply abandoned the Zimbabwe dollar and began to exclusively use the U.S. dollar and a smattering of other currencies from neighboring countries, such as the South African Rand, the Botswanan pula, the Mozambican metical and the Zambian kwacha. This brought an immediate end to Zimbabwe's hyperinflation, and inflation rates quickly returned to single digits.

Shortly after this "spontaneous dollarization" of the economy, the Mugabe government was forced to accept the demise of the Zimbabwe dollar and officially dollarize the economy. Although North Korea's hyperinflation is dwarfed by that of Zimbabwe (the second-worst in history), the example of Robert Mugabe's Zimbabwe is telling. If spontaneous dollarization and the official acceptance of that reality can occur in Zimbabwe, it can occur anywhere.

"Yuan-izing" North Korea

For the time being, it is doubtful that the North Korean government will allow the use of foreign currency, let alone officially dollarize the North Korean economy. That said, in much of North Korea — particularly in areas near the Chinese border — unofficial, spontaneous dollarization is already a reality. Perhaps the official use of the U.S. dollar is out of the question, but it is clear that the North Korean economy and currency are dysfunctional. So, why not yuan-ize the North Korean economy?

Far Fetched? Not really. After all, it is estimated that China accounts for more than half of North Korea's foreign trade and the lion's share of its foreign direct investment. Although the Jinping regime publically expresses disapproval of North Korea's belligerent antics, China continues to increase its trade and investments in North Korea. More importantly, China continues to develop the region along its border with North Korea, working around the clock to build bridges, highways, power links, and high-speed rail lines in China's northeast. Regardless of the rhetoric coming out of Beijing, China is clearly pursuing a regional development and economic integration strategy, centered on establishing sea access via the North Korean port of Rason.

The official adoption of the yuan by North Korea would certainly be a boon for China, but what about North Korea? Well, for starters, yuan-ization would put an end to North Korea's inflation woes, at least creating the potential for domestic economic growth. It would also facilitate increased trade with China and perhaps other countries, as well.

This would seem to run counter to the current U.S. policy stance against North Korea. But, consider the efficacy of sanctions against North Korea thus far. The North Korean regime has proved perfectly willing to let its people starve while it pursues nuclear capabilities. There is no evidence that continued elevated inflation will have any sort of destabilizing effect on Kim Jong-un's regime; just look at Zimbabwe, where Robert Mugabe still holds power years after the country's hyperinflation crisis.

For China, yuan-ization and economic reforms in North Korea, similar to the ones that China itself is undergoing, would result in a much less combative and dangerous neighbor. No wonder the Chinese are pushing for increased integration of China's Northeast region and North Korea. Indeed, it is possible that economic integration with a relatively more liberal China might help North Korea's economy begin to emerge from the stone age, towards something at least resembling a market economy.