“The meaning of the word “inflation” has changed. It used to mean rising prices; now it means high prices.”

So says Felix Salmon of Axios.

All economists should unite in screaming “NO!”

Inflation, as defined by economists, means a sustained rise in the general price level, equivalent to a fall in the purchasing power of a money unit (here a dollar). It does *not* mean high prices, which refers to an elevated overall price level at a single point in time.

Salmon understands this. His point is that the word “inflation” itself is being gradually redefined in popular parlance. The evidence? That the public still bemoans “high inflation” even though the annual consumer price level inflation rate has now fallen from a high of 9 percent in June 2022 to just 3.4 percent in April 2024.

You Could Still Argue Inflation Is “High”

First off, I think Salmon is uncharitable to the public on this. People are perfectly within their rights to consider inflation high today without being assumed to misunderstand its true economic meaning. That’s because inflation is indeed “high” according to three obvious metrics.

-

Relative to target. Official annual inflation measures are still above the Federal Reserve’s average annual target, despite having come down. Even the PCE index grew by 2.6 percent over the past year, which is above the 2 percent that the Fed aims for, and would have been the highest annual inflation rate post-2011 before the pandemic hit. So, official inflation rates are still “high” right now, relative to target.

-

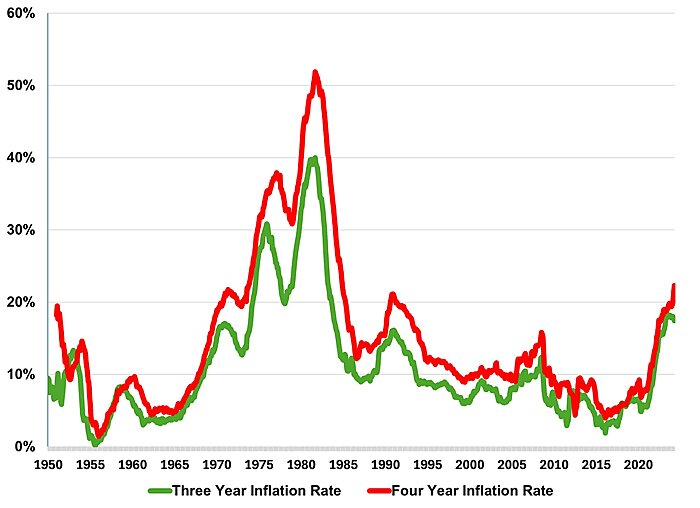

Over a longer period. The economists’ definition of inflation doesn’t specify that the time period over which you measure the change in the price level must be one year. True, the inflation rate usually referenced is an annual one, but people could just as easily conceptualize inflation over a three or four year rolling period, given they have just lived through a sustained surge in the price level. And, as the chart below shows, inflation over a three or four year period is indeed still extremely high relative to historic trends.

-

Relative to what people are used to. “Ah,” say Democrats, “but the rolling three to four year inflation rate was as high in the mid-1980s as today, but the public were much less likely to be upset about ‘high inflation’ then.” Well, yes. But they’d just lived through the 1970s and much, much higher inflation still. In relative terms, the early to mid-1980s saw inflation tumbling! In contrast, the recent high inflation followed three decades of very modest inflation. So compared to people’s prior experience, inflation has been “high” recently too.

Consumer Price Inflation Over Three and Four Year Periods Has Been At Its Highest Rate Since The Early 1980s

Correct Definitions Matter

If you think these justifications are too generous to the public and that we are really are seeing a confusion between inflation (as a rate of change) and the absolute price level, consider a thought experiment: If inflation now fell to target and continued at 2 percent per year forever more, would everyone say “inflation is getting worse” each year because the price level kept going up and up?

My guess is that the answer is “no.” And that really implies that the public aren’t permanently defining inflation as high prices, but are just judging the recent inflation over a slightly longer period or relative to more historic trends.

None of this is to deny public ignorance about inflation exists. Stephanie Stancheva’s survey work shows that not everyone understands that inflation is a sustained increase in prices. Survey work from Britain shows that a substantial minority there really do think falling inflation should mean falling prices.

Yet to the extent this is a problem, is it not up to journalists, commentators, and economists to explain what inflation really means and how it differs from a higher price level? Articles like Salmon’s merely confuse matters.