Among the many things that divide American conservatives today—beyond the fundamentals, I mean—is the extent to which the government should intervene in the U.S. economy.

On one side, you have Reaganite traditionalists who continue to push for relatively limited state involvement in markets. On the other, you have a nationalist “New Right” that’s far more comfortable with subsidies, tariffs, antitrust regulation, and other interventions—especially related to trade and industrial policy—as well as the more powerful bureaucracy that these policies require. And this latter group is none too shy about explaining that the Old Right’s continued economic humility reflects a market fundamentalism that’s simply out of touch with today’s economic, geopolitical, or cultural realities.

As we’ve discussed (a lot), there are plenty of reasons why I’m skeptical of the New Right’s economic vision. But recent events make me wonder if maybe they’re waking up to at least one of them: The inevitable role of politics in “interventionist” economic policymaking.

The last few months have seen many New Righters and New Right-adjacent folks openly complain about the Biden administration’s implementation of the very industrial policy that they’ve often championed. Just last month, Sen. J.D. Vance of Ohio grumbled in a hearing about the “counterproductive” social policy baked into the Biden administration’s implementation of the semiconductor subsidies—which he once hailed as a “a great bipartisan victory” for his state. He’s also lamented Biden’s industrial policy for electric vehicles (never mind its similarities to President Trump’s), while proposing his own version for internal combustion cars. Sen. Josh Hawley of Missouri, a fellow New Right fan of industrial policy, has done much the same thing. He’s blasted the Biden administration for its chip subsidy waivers related to China, for example, and railed against a Department of Energy official’s hob-knobbing with potential green subsidy recipients (which, to be honest, does look kinda bad!).

Beyond Capitol Hill, other New Righters have similarly embraced industrial policy but then railed against the very “Bidenomics” that relies on it. American Compass’ Oren Cass has now written not one but two op-eds in the Financial Times lamenting the Biden administration’s implementation of U.S. industrial policy—first the CHIPS Act and now the IRA—as, essentially, right in theory but wrong in practice (e.g., lacking ambition, picking the wrong industries, bogged down by inapt social priorities). He’s certainly not alone. In case after case—and op-ed after op-ed—New Righters have effectively been reduced to claiming that, actually, real American industrial policy has never been tried.

No, really.

The Permanent Majority Fallacy

In these comments, New Righters are getting mugged by two harsh political realities (ironic, yes, given their criticism of the “Old Right” as out of touch ideologues).

First is the fact that, no matter how popular a political party may be today, they’ll eventually be out of power. As Duke’s Mike Munger has long tried to explain, aspiring technocrats on the left and the right seem to forget this when proposing their favored versions of industrial policy. Instead, Munger notes the planners like to portray their preferred policies as being implemented by a “magical state unicorn” (or, at the very least, wise and unbiased technocrats just like them—if not actually them). Yet these policies are always conceived and implemented via the political process, and by the politicians and bureaucrats it churns out (aka “men and women who are doing their best, but who face electoral pressures and very short time spans to make decisions”). Sometimes, they’re even implemented by a person like Donald Trump.

This obvious political reality creates serious problems when implementing tariffs, industrial policy, and many other types of subsidies, mandates, and regulations that are championed by economic populists today.

For starters, perpetual short-termism and electoral vulnerability distort policymakers’ information and incentives. They end up crafting and implementing a policy in far different ways from not only how market actors risking their own capital would, but also how idealistic technocrats imagine they should. Thus, we get clunky “green protectionism” and politicized producer subsidies instead of non-discriminatory consumer subsidies or a carbon tax. Or we legislate “guardrails” to prevent U.S. semiconductor subsidies from flowing to China, only to see those get repeatedly waived because it’d harm producers’ bottom lines or raise geopolitical problems. Or we send one-off subsidies to “safe bet” companies, technologies, or industries—ones that don’t need government help (but won’t risk public ire)—instead of long-term commitments to riskier, cutting-edge ideas that might gain from non-market backing. And, of course, policymakers with their names tied to struggling projects often keep them afloat for years instead of pulling the plug like market actors (or disinterested wonks) would. (See this recent podcast discussion for more.)

Just as importantly, the political process can cause the entire target and direction of a certain economic policy to change in a short period of time. Put simply, because there is no permanent majority—no matter how many times we keep hearing about it—any law the party in power enacts or champions will, assuming it’s not a one-time jolt of cash or something like that, eventually be put into the hands of the other party. And that party very often—especially today and especially outside of national defense—has different economic, social, and environmental priorities, different core constituencies, and even different philosophies about how and when the federal government should act in the economy. As we’ve learned all too well in recent years, Democrats’ “emergencies” and “crises” are a lot different from Republicans’, and our wildly-vacillating “emergency” policies keep reflecting that.

You can see this political dynamic play out all the time, beyond the recent spate of the pandemic and industrial policy. Seemingly not a year goes by in which an ambiguous law, once passed or used by one political party to favor its preferred objectives or interest groups, is then used by the other party to help an entirely different goal or group—sometimes in the exact opposite way. Many on the left, for example, have been prodding the Biden administration to impose a broad set of “carbon tariffs” via the “national security” law Trump used to protect the (not-so-green) steel industry. As we discussed last week, Biden is kinda-sorta trying to go down that path right now. Whether good or bad, Biden’s “green” industrial policy is very different from the “brown” industrial policy his predecessor championed, even though they’re using the same law (and, for steel, even the same measure) to pursue it. This dynamic certainly isn’t limited to trade, either: Trump used U.S. fuel economy (CAFE) regulations to stymie California’s and other states’ stringent fuel economy standards—the same regulations Biden used this year to effectively California-ize the federal rules.

The list goes on and on. Literally as I write this, in fact, another example crossed my desk:

The risk (and reality) is truly omnipresent.

The “Political Process” Fallacy

Some of the New Right’s advocates acknowledge the problem of politics infecting industrial policy and other interventionism but often counter that free market policies face the very same problems because they’re the product of the very same process. That’s the second fallacy they’re prone to, and their rebuttal fails for again-obvious reasons.

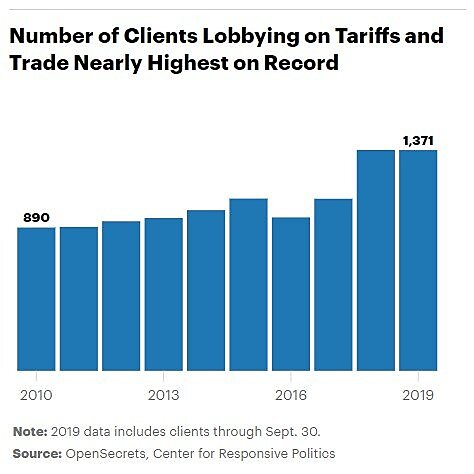

For starters, new economic interventions—tariffs, subsidies, mandates, whatever—maintain a clear role for the government to act in the market at issue and for private parties to lobby the government instead of focusing on their actual businesses. New subsidies appropriated by Congress aren’t just tossed out some Capitol window (though that would be kinda cool). Instead, they’re delivered by a newly empowered bureaucracy, which must determine firm eligibility, priority, and other things—things that potential subsidy recipients will suddenly become quite eager to demonstrate. For example, both the IRA and CHIPS Act were accompanied by not only a lot of new hires in the relevant government offices, but also a lobbying “bonanza” (or “frenzy” if you prefer) as corporations worked to get their hands on the cash:

Several of Washington’s top lobbying firms reported record-breaking earnings in the third quarter of 2022, according to figures shared with The Hill, defying expectations that lobbying revenue peaked earlier this year.

Hired guns worked overtime to influence the Inflation Reduction Act and the CHIPS and Science Act, both of which became law in August. They’re now turning their attention to government agencies that control the flow of billions of dollars in lucrative new grants authorized by the bills.

Oftentimes, this entails entirely new corporate players in the lobbying game, players that can become Washington mainstays who fight like hell to keep the rents they’ve won. “The Biden administration’s climate change agenda has spurred a lobbying boom driven by mineral and battery companies seeking a share of billions in federal incentives,” E&E News reported in April. “More than 30 of those companies retained lobbying firms for the first time since President Joe Biden took office.” None of that happens if there are no subsidies to obtain.

New taxes and regulations, meanwhile, are inevitably accompanied by attempts from the affected private parties to change or avoid the policy, minimizing financial costs or maximizing benefits via political channels. Most commonly, this comes from ad hoc exceptions to the general rules of the road because of the costs they impose on certain groups (who, of course, will complain loudly to their representatives). Ethanol mandates have carveouts for small refiners; CAFE regulations have exceptions for light trucks; shippers seek Jones Act waivers during emergencies; and those metals tariffs had a famous (infamous) system for U.S. manufacturers to win an “exclusion” for their imports. Similar to the subsidy panhandling, these desired exceptions require parties to petition the government via a process that inevitably involves more politics, especially where companies or interest groups opposed to the exception also get to weigh in. When those steel tariff exclusions were implemented, for example, lobbying activity among both the steel industry and steel consumers skyrocketed—a boon for K Street lobbyists but rough sledding for people who can’t afford them.

In one especially ridiculous case, a single tariff exclusion request for a certain Pennsylvania manufacturer ended up involving 24 members of Congress (14 for, 10 against). The editors at the Wall Street Journal rightly described the ordeal as “a sorry example of how tariffs have become another opportunity for government intervention based on political power, not business necessity.” Indeed.

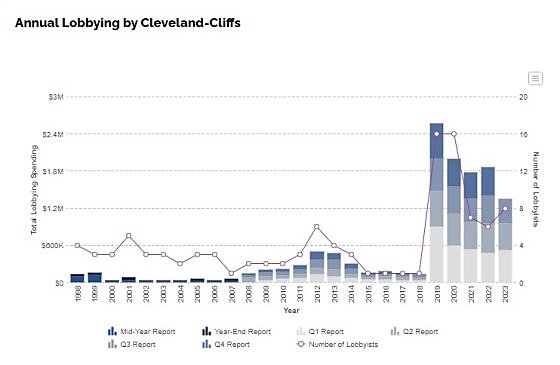

As with those subsidies, many firms that would have never thought of petitioning Washington for anything—especially small- and medium-sized businesses—got into the lobbying game. In my 17 years of practicing law, in fact, the only time my primary legal advice to a client was to “get a lobbyist” was when the Trump tariffs came along. (Yes, it was very depressing.) Perhaps the starkest example comes from Ohio-based steelmaker Cleveland Cliffs, which was a relatively small player in D.C. until the steel tariffs were implemented:

Similar processes to modify existing laws or regulations—usually via a pre-set periodic review to account for market changes—produce similar government and lobbying efforts, as anyone remotely familiar with the EPA’s periodic adjustment of U.S. biofuel blending mandates knows all too well. (This year, it produced a “lobbying crush” from producers, consumers, and middlemen.) No biofuel industrial policy, no process, no private sector “crush.”

And, as we discussed with respect to proposals to extend tariffs to small-dollar imports, mere compliance with and enforcement of these laws also requires extensive state and private sector involvement that policies removing government from a market or transaction simply don’t have. Even things that seem easy often aren’t, as this timely thread from economist Jeremy Horpdahl shows:

Finally, interventionist policies have a way of reverberating throughout an economy that free market policies typically don’t. When the government taxes one group to help another, it signals to the former that it might be able to win similar treatment. For example, when Trump’s steel tariffs raised U.S. steel nail producers’ costs—making them globally uncompetitive—they won their own “national security” tariffs, as well as new antidumping duties, to block imports. As Bloomberg reported shortly after the tariffs were implemented, the nail guys certainly weren’t alone:

Makers of steel wheels, safes and other products want the U.S. to impose tariffs on goods by their Chinese competitors, which aren’t among the products targeted so far. They say the duties the U.S. imposed on steel and aluminum imports raised their costs but didn’t affect finished goods made in China and sold here—setting up a potentially damaging Catch-22.

Subsidies and other types of government support can also snowball, as unsubsidized companies seek equal footing with their subsidized competitors—or as subsidies to one industry give an unrelated industry the green light to push for their own government support. When the government announces that it’ll pick winners based on “national security” or whatever, every company is suddenly going to start telling the feds it’s essential to national security or that its overseas competitors threaten it. And peer firms will too. (This is a longstanding joke in Washington.)

Indeed, a new study in the journal Public Choice examined lobbying expenditures between 1999 and 2020 and found that U.S. firms increased their own lobbying expenditures in response to increases in competitor companies’ lobbying efforts. The paper further found that this relationship is stronger in industries with more government regulation, and that “non-lobbying firms are also more likely to start lobbying when their peers increase their lobbying.” In short, the more government regulation, the more likely companies are to enter a lobbying race.

Not all of this snowballing, however, is the result of lobbying at the newly-opened government trough. Instead, policymakers often pursue new government interventions in response to ones they already have in place but—typically for political reasons—they’re loath to remove. Beyond bailouts and other life-support for dying state-sponsored projects, we get new subsidies for carbon-capture technology at dirty corn ethanol plants, or to build expensive, low-tech ships at uncompetitive (thanks to the Jones Act) shipyards. Or we get billions in farm subsidies to buy off American farmers harmed by Trump’s trade wars, or regulations to cap high rents caused by local zoning restrictions. I could go on. Some industrial policy fans even went so far last year as to propose “fixing” the baby formula crisis—so obviously caused by bad government policies—by creating a new, $20 billion “national economic development council.” Now, with recent wind and EV industry struggles, some are already wondering if more subsidies or bailouts are on the way.

Free market policies can, of course, create their own issues—usually, like tax reforms or U.S. trade agreements, because of the messy political process needed to implement them (and the vestiges of taxation, regulation, or protectionism it maintains). But their end result after legislation passes is less government involvement in the market and less private sector attention to that same government. Subsidies, tariffs, regulations and other interventions, by contrast, generate more of this involvement, meaning more opportunities for elected officials, bureaucrats, corporations, unions, and their lobbyists to use these laws, however well-intentioned they might be, for political and financial gain.

Summing It All Up

There was a time when almost everyone on the right got these points and committed to a relatively simple, humble, and transparent tax and regulatory system that would—with some hotly-debated exceptions—minimize the government’s involvement in our daily economic lives. Sometimes I really do feel like I’m taking crazy pills for feeling the need to devote 2,500-plus words to the obvious and very old political realities with which interventionist economic policies inevitably collide. But the “New Right” seems to have forgotten it all, choosing instead to believe that they’ll either be in power forever or that their “conservative” policies really will be implemented by Munger’s “magical unicorn”—one impervious to political short-termism and all the other baggage that inevitably accompanies a bigger, more powerful government.

I’d hope that after witnessing more than a year of a Democrat implement industrial policy, “green” or otherwise, in ways they decidedly don’t like, Vance, Hawley, and their cadre of online supporters might reconsider their plans to hand the government (and, eventually, “the Left”) more control over the U.S. economy. So far at least, it seems that this reality hasn’t done enough mugging just yet.