Welcome, all you “greedflation deniers.” That’s the label Odd Lots host Tracy Alloway uses to describe those of us who doubt that corporations’ profit-seeking meaningfully drove the recent high inflation.

Alloway caricatures our view as “greedflation couldn’t have caused high prices because companies didn’t suddenly get more greedy in 2021, or 2022, or whenever.” But, she argues, the “greedflationist” case is not that simple. Drawing on Isabella Weber’s research, “greedflationists” instead claim that rising costs due to the pandemic or Ukraine war-related supply shocks created an environment where price hikes became easier for businesses to “coordinate.” Essentially, in a world of rising costs, businesses are more inclined to raise prices, expecting that their competitors will follow suit and that their consumers are expecting prices to rise.

Of course, a standard macroeconomic model of aggregate demand and aggregate supply would predict that a negative supply-shock would raise prices across firms as real output falls. Without prices rising to reflect that reality, we’d see shortages of products, more layoffs, and deteriorations in product quality. But greedflationists see something more nefarious at play. They point to the concurrent boost in profits we saw for many firms as evidence that something is amiss — that this is really about firms somehow exercising market power.

In The War on Prices and here I’ve gone out of my way to accurately represent this greedflation “theory.” Recently, even Weber acknowledged my “pretty accurate summary” of her thinking. So while it’s legitimate to acknowledge that there’s no inherent reason why corporate greed or market power should have suddenly spiked in 2021–2022, my critiques have gone far beyond pointing this out. Fundamentally, I think the economic theory of Weber’s analysis is faulty.

Which brings us to her latest paper with co-authors Evan Wasner, Markus Lang, Benjamin Braun, and Jens van ’t Klooster. They use large language model sentiment analysis on company earnings calls from 2007 to 2022 to supposedly test if companies expressed more optimism about profits when costs were rising across the economy.

Their hypothesis is straightforward enough: if firms found it easier to coordinate price hikes when broad input price shocks occurred then we’d expect companies to sound bullish when all firms’ costs were going up, because they’d be able to take advantage and raise prices. In contrast, if only their own costs were going up in isolation, they’d sound negative, because this cost increase would be squeezing their profits. They say their results show exactly that.

Now, I’ve long critiqued the underlying theory behind this hypothesis, arguing that Weber doesn’t take competition or consumer behavior seriously enough.

First, in any market with modest competition, if some firms hike prices for profit, other companies or new entrants have strong incentives to undercut those prices. This makes broad “coordination” or even tacit collusion highly unlikely—unless, of course, something in the economic landscape has fundamentally changed.

Weber must then explicitly assume that “incumbent firms in concentrated markets tend not to lower prices, since this risks launching a price war and a destructive form of competition that drives down market-wide profitability, which firms with substantial market shares try to avoid.” This assumption, though, defies both logic and experience, because firms clearly often engage in such competition in concentrated sectors. For instance, despite the high concentration of a few large airlines (and high start-up costs combined with characteristically low profit margins discouraging entry), the industry today often sees competitive price cuts (at least, it has since airline pricing was deregulated).

Second, and more damningly for Weber’s theory, firms can only go as far in raising prices as consumers’ ability and willingness to pay them. If many firms across sectors suddenly raised prices aggressively at once, consumers of even “essential” goods would have less money left over and so cut spending elsewhere, reducing demand and so prices in other sectors. To a first approximation, there’d be no reason to expect an overall uplift in inflation. No, a broad, persistent inflation requires consumers to have more money to spend overall—at which point it’s surely more accurate to say that the macroeconomic stimulus allowing this is the real driver of inflation.

Let’s put theory aside, though, and look at Weber’s new analysis. The results are summarized as: “The sentiment firm executives express when discussing increases in their own input costs is more positive in the presence of large, economy-wide cost shocks and supply disruptions than in their absence.”

These results come from a regression analysis. The dependent variable is the “Cost Increase Sentiment Index,” which reflects the sentiment of executives regarding cost increases as derived from earnings call transcripts. A positive index value indicates a favorable view of cost increases, implying confidence in protecting or expanding profits.

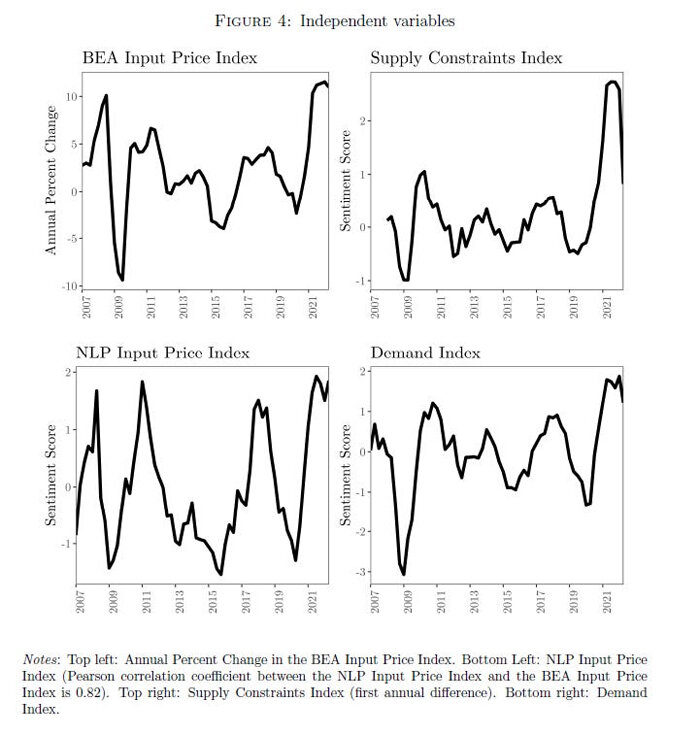

The main independent variables are the BEA Input Price Index, which measures changes in input prices across the economy and which the authors interpret as a proxy for cost shocks; a Supply Constraints Index, capturing sentiment related to supply shortages expressed in the same earnings calls; and a Demand Index, which reflects expressed sentiment related to demand conditions. The regression results suggest that rising costs and supply constraints correlate with more positive sentiment among firms. The authors interpret this as evidence that cost shocks and supply constraints create a kind of implicit coordination mechanism, making it easier for firms to raise prices without fear of losing competitive ground. That, they think, is a key explanation for the inflation of 2021 onwards.

There are huge inherent problems in regressing business cost sentiment on other sentiment variables from the very same earnings calls. I have other doubts about the broader methodology too. But there’s a bigger economic problem here: this whole analytical framework amounts to “reasoning from a price change.” What do we mean? Well, input costs are prices, too! Sure, they can indeed rise due to supply shocks—like a gas price surge from the Ukraine war. But they can also go up due to surging demand fueled by excessive macroeconomic stimulus, which pushes up demand for all inputs, including oil and everything else.

Yet the regression’s input cost variable doesn’t distinguish between these causes and certainly cannot be interpreted as just “cost shocks”. This is important for understanding the results: any positive correlation with sentiment is being interpreted by the authors as evidence of firms “liking” cost shocks, when, in reality, both improving sentiment and rising input costs might reflect a third factor: rising demand, driven by macroeconomic stimulus.

In fact, rising input costs due to surging spending are exactly what most inflations—including much of the recent one—look like: too much money in circulation pushes up prices across the board. By treating the “input costs” variable as if it solely reflects supply-side cost shocks, the analysis thus ignores an obvious possibility—that firms’ positive sentiment, correlated with rising inputs costs, reflects them being bullish about an underlying surge in demand.

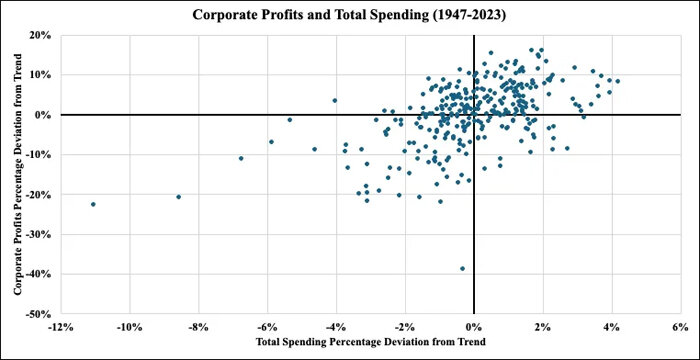

As my own previous analysis with Bryan Cutstinger has shown, historically above-trend spending levels driven by expansionary macroeconomic policy juicing demand tends to be good for short-term profits. One reason might be that retail prices usually go up more quickly than stickier wage costs (even if other input costs rise). And in this recent inflation, nominal GDP — synonymous with total spending on final goods and services — surged far higher than its pre-pandemic trend. Weber’s interpretation of her regression, though, dismisses the possibility that this is behind any positive sentiment. To reiterate: her results could just as easily reflect firms’ positivity due to rising demand and this spending improving firms’ immediate prospects for profits, even as input prices broadly rise because of the exact same forces.

The same issue of conflating supply and demand pressures plagues the “supply constraints” sentiment variable. Executives might refer to “supply constraints” when there’s an unexpected shortage of inputs, but they may also use the same term when demand surges push production close to the company’s capacity limits. This mix-up, again, means the regressions lack clear identification of the underlying forces at play. Yes, Weber might try to “control” for demand with its own sentiment index, but there’s no inherent reason to expect that earnings calls will accurately delineate between supply and demand factors here.

For further suggestive evidence of the problem, look at her charts on page 30. It’s striking how the “demand,” “supply constraints,” and cost indexes all rise together during the recent inflation—a warning signal that a broader force, like macroeconomic stimulus, may well be influencing them all.

To put it simply: this analysis tells us little to nothing about the true, underlying macroeconomic causes of the recent inflation. If you think inflation is determined by imbalances between total money spending (demand) and total real output (supply), as most greedflation critics do, then it’s obvious using standard macroeconomic models why either large aggregate supply-shocks or excessive stimulus make it necessary for many firms to raise prices at the same time.

There’s also, though, a perfectly plausible explanation for why firm sentiment about costs can be positively correlated with rising input prices and perceived supply constraints. No, it’s not because rising input prices always reflect negative supply-shocks that suddenly enable firms to coordinate or collude in the pursuit of profits. It’s that an excessive macroeconomic stimulus driving up nominal GDP can drive up both many input prices and juice firms’ short-term profitability at the same time.

Source: Bourne and Cutsinger (2024)

If this research were just an intellectual curiosity, then that would be one thing. But Weber is using her analysis to push damaging policy change. The paper says: “If, by contrast, firms’ pricing behavior and cost shocks played an important role in stoking inflation, the global economy will be vulnerable to inflation from similar shocks resulting from climate change, trade wars, and mounting geopolitical tensions. Theories and models must be updated and policies put in place to prevent such future price hikes.” The sorts of price controls she advocates are, of course, a recipe for product shortages, deteriorations in quality, and black markets.