Does it feel like you’re walking on eggshells lately when talking about politics? You’re not alone. A new national survey of 2,000 Americans I conducted at the Cato Institute finds that 62 percent of Americans say the political climate these days prevents them from saying what they believe because others might find it offensive. This share is up from 58 percent in 2017.

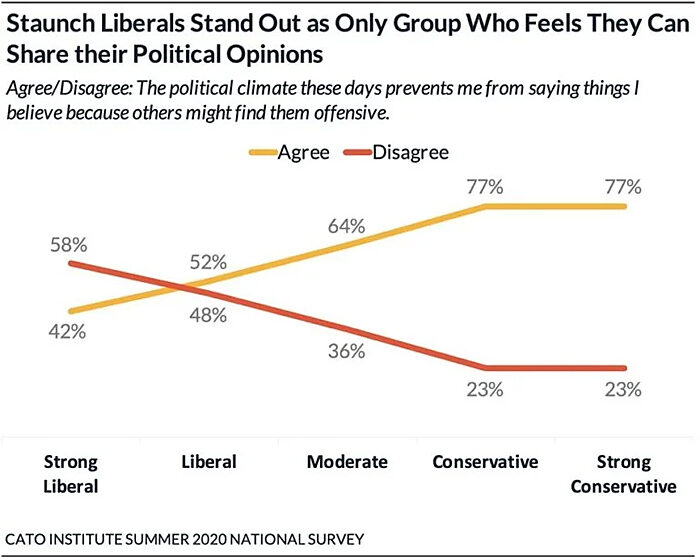

Notably, self-censorship is not a partisan issue. Majorities of Democrats (52 percent), Independents (59 percent), and Republicans (77 percent) all agree they have political views they are afraid to share.

Only Far Left Feels Free to Express Political Opinions

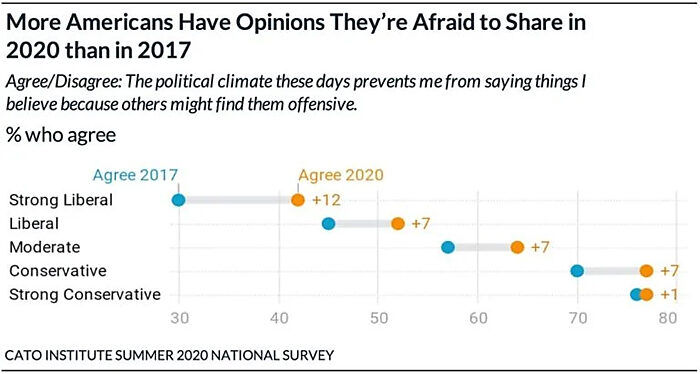

Only staunch progressives reach a majority (58 percent) who feel free to speak their minds. But centrist liberals disagree: a slim majority (52 percent) feel they cannot say what they believe in the current environment—up from 45 percent in 2017. Yet, just a few years ago, liberals felt they could openly express themselves (54 percent). In fact, nearly all political groups are self-censoring more today.

Could this simply be people self-censoring bigotry and prejudice? Perhaps for some. But the survey found that large majorities or near majorities of people across race, sex, and income all feel like they can’t say what they believe. That means this effect is not simply concentrated in one identity group, but pervasive across all.

The survey found that nearly two-thirds of Latino Americans (65 percent), Asian Americans (65 percent), white Americans (64 percent), as well as nearly half (49 percent) of African Americans, feel uneasy sharing their views. Similarly, both men (65 percent) and women (59 percent) self-censor.

Some may ask, perhaps the 62 percent are simply being polite and avoiding unnecessary offense? This is likely true for some. But the survey data offer some warnings against this interpretation.

Self-censorship is on the rise since 2017. It’s up 12 points among progressives (30–42 percent), and up 7 points among centrist liberals (45 to 52 percent), moderates (57 percent-64 percent), and centrist conservatives (70–77 percent). Only staunch conservatives haven’t changed much, perhaps because 76 percent said they were already self-censoring three years ago.

Also, consider how the question was asked. Respondents were asked if the political climate prevented them from saying things they believe because others might find their ideas offensive. It did not ask if standards of decency and politeness prevented them from being rude.

Also, centrist liberals flipped from feeling free to express themselves (54 percent) in 2017 to now feeling they no longer can (52 percent) in 2020. These data align with the largely liberal signatories of the Harper’s open letter defending political expression and criticizing cancel culture. These writers and scholars were not decrying being polite, but the spread of an illiberal zeitgeist that restricts free thought and discourse.

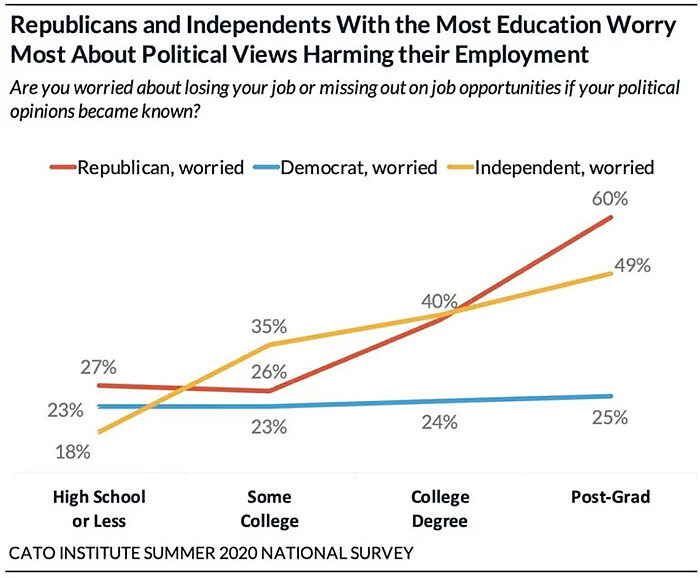

One-Third Worry about Their Views Affecting Careers

Causing offense isn’t the only thing people are worried about. Many are concerned about their livelihoods and the ability to provide for their families. Almost one-third (32 percent) of employed people say they worry they could get fired or miss out on job opportunities if their political views became known.

It’s not just one side of the political spectrum who feels this way. Similar shares of liberals (31 percent), conservatives (34 percent), and moderates (30 percent) are all worried about their jobs. These fears cut across demographics as well: 38 percent of Hispanic Americans, 31 percent of white Americans, 22 percent of African Americans, 27 percent of women, 35 percent of men, 36 percent of people earning less than $20,000 annually, and 33 percent of those earning more than $100,000 annually all fear “cancel culture.”

People with more education are more likely to worry about their politics affecting their career trajectory. But Republicans and Independents are driving the difference. Sixty percent (60 percent) of Republicans and 49 percent of Independents with post-graduate degrees fear being penalized at work if their political opinions became known, compared to 25 percent of Democrats with post-graduate degrees. Less of a gap exists between Republicans (27 percent), Democrats (23 percent), and Independents (18 percent) with high school diplomas.

It could be that the industries that employ more people with college and post-graduate degrees are lopsidedly left-of-center, leading independents and Republicans to self-censor. It could also be that independents and Republicans learn in college and especially in graduate school that their political views are penalized.

Left Especially Supports Firing Opposition Donors

Are people overreacting? Perhaps not. The survey found that nearly one-third (31 percent) of Americans would support firing a business executive who personally donated to Donald Trump’s campaign. This share rises to 50 percent among staunch progressives. It’s not just the far left willing to punish their political adversaries. Almost one-quarter (22 percent) of all Americans and 36 percent of staunch conservatives would support firing Biden donors as well.

Although most Americans overall oppose firing either Trump or Biden donors, it’s important to recognize that many industries and regions may be comprised of people with rather homogenous political views. Take, for instance, industries like academia, media, Hollywood, and tech, which overwhelmingly employ people who are left of center. Or industries like mining, oil and gas, home building, automotive, and construction that are largely right of center.

Even within industries, you can find clusters of political homogeneity. For instance, The New York Times reports that 77 percent of infectious disease specialists are registered Democrats while 67 percent of surgeons are registered Republicans. So an industry that slants left or right could reach a majority (or close to it) in favor of firing Trump or Biden donors in their midst.

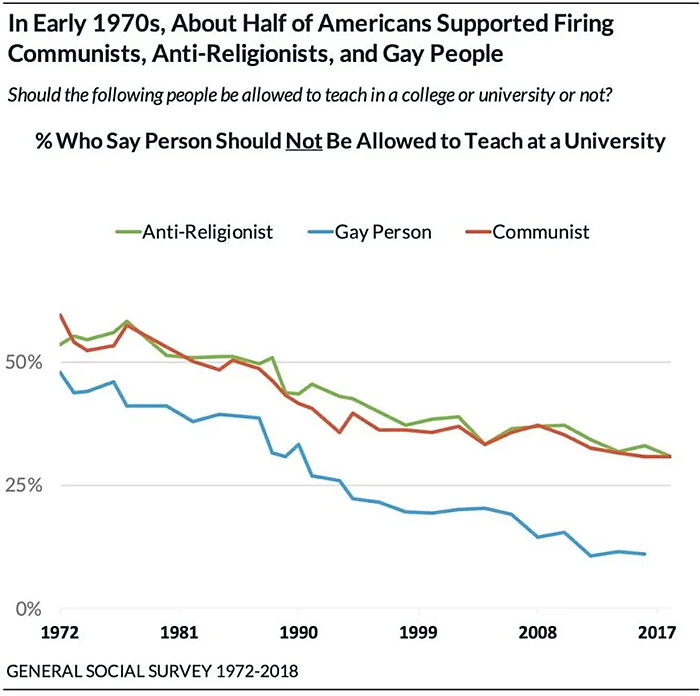

‘Cancel Culture’ Isn’t New

In his 1940 essay, “On Freedom,” Albert Einstein argued that scientific progress depends on open discourse, and that “laws alone cannot secure freedom of expression; in order that every man present his views without penalty there must be a spirit of tolerance.” This spirit of tolerance goes beyond constitutional protections from government censorship. Private censorship can also raise the cost of expression and thereby stifle open discourse.

Although the principles of free expression and tolerance are deeply engrained in American culture, many throughout American history have resisted this pluralistic approach. In other words, so-called “cancel culture” is not new. Political scientists have long documented this urge in American political life, found on both the left and right.

Dating back to the early 1970s, the General Social Survey found that 60 percent of Americans supported firing a communist college professor, 52 percent supported firing an “anti-religionist” professor, and 48 percent thought a gay professor shouldn’t be allowed to teach at a university. Notably, there wasn’t much difference between Democrats and Republicans.

For example, in 1973, 53 percent of Republicans and 52 percent of Democrats thought a gay person shouldn’t be allowed to teach at a university. Although far fewer today, substantial shares continue to support severe economic penalties for professors who are gay (11 percent), communist (31 percent), or against organized religion (31 percent).

Why Some People Want to Punish Others for Their Ideas

Why do some want to inflict severe punishment on their fellow Americans over political disagreements? This desire to silence one’s political opponents is separate from efforts to marginalize overtly bigoted speech and behavior—efforts most Americans support. But what explains the psychological motives behind cancel culture that increasingly capture innocent people and shut down political discourse?

Research in political psychology has found some personality styles are more demanding of conformity and more willing to squash dissent. In academic parlance, it’s called the “authoritarian personality.” (See here, here, and here.)

In response to World War II, academics tried to identify what personality types would be drawn to totalitarian ideologies. Much of this research inappropriately ascribed the authoritarian personality near-exclusively to the political right. However, new research is finding evidence that there is both a left-wing and right-wing variant of the authoritarian personality.

Thus, these authoritarian tendencies may manifest in different ways and in reaction to different issues, but there appear to be some core psychological tendencies shared between left-wing and right-wing “authoritarians.” Observing how both groups think alike can help pinpoint the core features of this illiberal style in American politics.

Surveys that identified left-wing and right-wing “authoritarians” found that both scored significantly higher on psychological measures of dogmatism, confirmatory thinking, moral disengagement, need for closure, affective polarization, political certainty, and tolerance of political violence, and both scored significantly lower on intellectual humility.

In other words, Americans with left-wing or right-wing authoritarian tendencies are more likely to be dogmatically rigid and eschew nuance. A key feature is a failure to recognize the possibility that some of what they assume, observe, or interpret might be wrong. They tend to believe they have all the facts.

Partly contributing to this is the tendency to discount or ignore disconfirming evidence. But it’s more than just rigid, confirmatory thinking. “Authoritarians” begin to dehumanize their political opponents, assume the worst possible of intentions, lack compassion for them, and then rationalize and even support harm against them. While each of these tendencies independently may not mean someone has authoritarian inclinations, these traits combined make one more likely to seek to squash political dissent when threatened.

Threat, particularly ideological threat, is the necessary ingredient to activate people with latent authoritarian tendencies and motivate their desire to punish others. Social media may have a catalyzing effect in activating latent authoritarianism on left and right, as it constantly barrages people with ideas, images, and videos that threaten their ideological boundaries, norms, and authorities. In short, some social media companies could be making Americans more authoritarian.

Why We Should Care

There are many reasons to resist this authoritarian urge to squash dissent. The first is that scientific progress, and by extension, the improvement of human well-being generally, requires free thought and open discourse. As Jonathan Rauch explains in his book, “Kindly Inquisitors,” the scientific method breaks down when people become reluctant to ask questions, be creative, challenge each other, and seek out and understand evidence.

Further, as Thomas Chatteron Williams explained in a New Yorker interview, the culture of canceling signals to people what the boundaries of “acceptable” ideas are or else suffer severe economic and emotional punishment. Thus many “steer far clear of the boundary,” causing a “narrowing…stifling effect on not just speech but on thought,” he explained.

Yet silencing people and stifling free thought isn’t an effective long-run strategy. It rarely changes minds. It just shuts down civil discourse and prevents people from having opportunities to modify their ideas in the face of new information. Instead, people hold onto their opinions, and just sweep them under the rug.

Political opponents’ disengagement doesn’t necessarily mean victory. Americans still vote. And their political views, silent or expressed, affect how they vote. Persuasion is necessary to change how people think and thus who and what they vote for. But persuasion is hard and requires open dialogue.

Social psychologists have found evidence that we aren’t very good at updating our opinions by ourselves. We need other people we respect to ask us to explain our views and then challenge us with new considerations. It’s typically through this back and forth process that we update our views when people we trust present us with new, compelling information.

But this only works when we feel comfortable to engage in a dialogue. Thus it is only with open dialogue that people’s opinions can be examined, understood, or reformed. Thereby, the best long-term strategy is persuasion, not silencing. And persuasion requires open debate.

I propose we take this wise advice from social psychologist Jonathan Haidt: let us first try to “give less offense” and then let us make efforts to “take less offense” ourselves.