Dear Capitolisters,

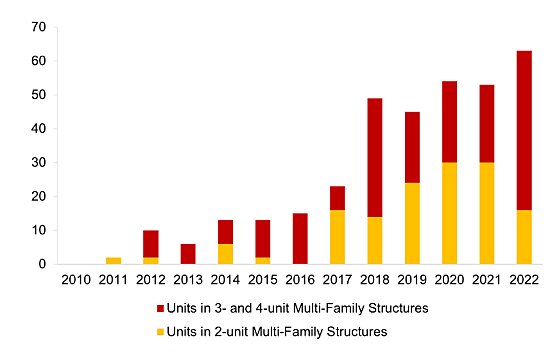

One of the more common (and frustrating) economic policy claims you’ll see in Washington is that the fundamentals don’t apply to a certain, “special” industry or market. As we’ve discussed, of course, real market failures necessitating government action can and do exist, and the real world is more complex than your basic supply-and-demand graph. Yet the failures are rare, and the fundamentals do apply to the vast majority of markets (with the usual wrinkles and details thrown in).

One of the most common of these “special” markets—maybe the most common outside health care—is housing. Activists and impartial observers join with mainly left-wing academics and self-interested locals to argue that, because the standard supply and demand models don’t work, building more housing in a certain locality won’t actually temper prices there. Thus, so the arguments go, state and local governments shouldn’t permit more/denser construction and should instead offer generous consumer subsidies or rent controls. As we’ve discussed here repeatedly, there’s a good and growing pile of history and economics literature debunking these claims: In general, allowing more housing to be built—mainly by reforming local zoning and other land-use regulations—will moderate the prices of both new and existing housing stock, while subsidies (especially when provided without the aforementioned supply-side reforms) and rent controls typically cause more problems than they superficially solve. The laws of economic gravity, in other words, still apply.

Yet claims to the contrary persist. For example, my Cato colleague Ryan Bourne reported last week that dozens of economists wrote the federal government advocating national rent control and suggesting “that the economics of rent control itself is being fundamentally rethought, with economists more likely to reject the old Econ 101 supply and demand predictions.” The letter was part of a broader campaign of academics, politicians, and environmentalists advocating more rent regulations, again premised on the notion that economic fundamentals have broken down in the housing sector. A few weeks ago, meanwhile, the thoughtful and popular blogger Scott Alexander wrote a long piece questioning whether building more housing actually makes prices lower than they’d be without new construction (and suggesting it’s actually the opposite effect). And in the real world, high inflation and skyrocketing rents and home prices have pushed many municipalities to toy once again with rent control.

Bourne does a great job dismantling the economists’ letter claim-by-claim, relying on various studies to prove his points. But there’s also a real-world experiment going on in Minnesota that reinforces the papers’ conclusions and the “Econ 101” explanation for America’s housing problems. We’ve gone over some of this in past newsletters so here’s a quick recap: In 2018 Minneapolis announced a “2040 plan,” that, starting in 2020, made the city the first in the country to abolish single-family zoning and allow three-unit “triplexes” to be built almost everywhere. The plan also eliminated other land use regulations, such as parking minimums, that hindered multifamily construction, and it “upzoned” various transit corridors to let bigger structures be built without special municipal approvals. At the same time, the other Twin City, St. Paul, hasn’t (yet) deregulated in a similar fashion and—as we briefly discussed in December—implemented strict new rent controls, thus providing us with a unique real-world experiment of both housing deregulation and rent control in neighboring cities. So, how has this natural experiment worked out?

So far, just as we’d expect.

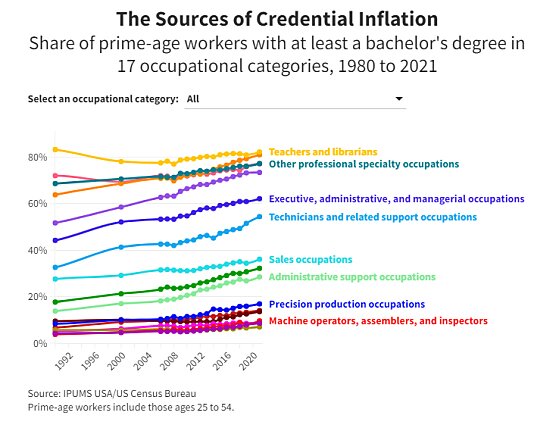

In particular, new data show that allowing private investors to build more housing does, in fact, moderate prices citywide and have large and important knock-on effects for a liberalizing community. First, economist Tim Maltman (h/t Scott Sumner) recently did a deep dive into how Minneapolis’ housing reforms have affected both the supply of new housing and area housing costs. While acknowledging that various factors—COVID-19, previous reforms, etc.—are also at play, he finds several clear indications that deregulation is working. First, the city is “leading major American Midwestern cities in housing construction per capita over the last five years,” despite having slower population growth than Columbus and Omaha.

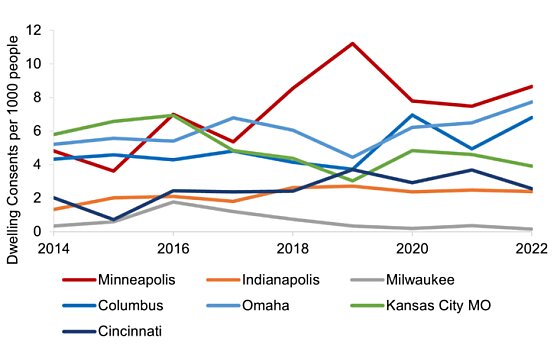

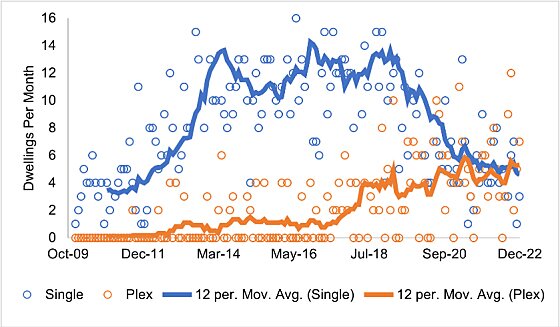

Key among this construction is smaller multifamily construction (“plexes” with just a few units), about half of which wouldn’t have been possible under the city’s previous, more regulated system:

This isn’t (yet) a huge share of total unit construction, but its growth—up 480 percent since 2015 and staying strong during the pandemic even as single-family construction has struggled—is remarkable during a time of high inflation, high interest rates, and persistent supply chain problems:

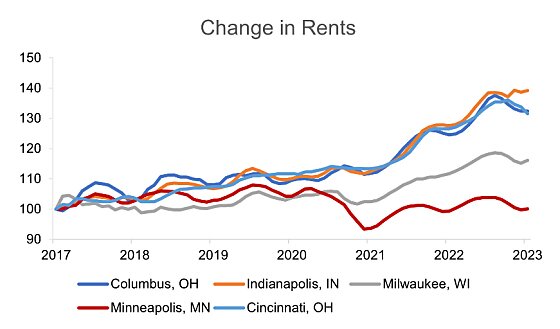

And all this construction appears to be affecting prices in Minneapolis. Remarkably, Maltman finds that citywide rents have actually declined in nominal (not inflation-adjusted) terms since before the pandemic, and that the decline just so happened to begin two years—i.e., the typical lag from start to finish of a construction project—after construction permits (“consents”) spiked. Meanwhile, most other Midwestern cities saw nominal rent increases of more than 30 percent over the same period. Even Milwaukee, which actually lost population (Minneapolis gained), saw rents increase by more than 10 percent. Other data sources, he notes, confirm these trends, as do other reputable indicators of housing affordability and data on homelessness (which typically correlates with housing affordability, though it’s obviously more complicated than that) in Minneapolis.

These data thus confirm, as Maltman put it, that “jurisdictions that facilitate more supply often see much lower housing costs and rents,” and that these reforms can generate high levels of new supply in spite of economic headwinds like the ones currently facing the U.S. housing construction industry.

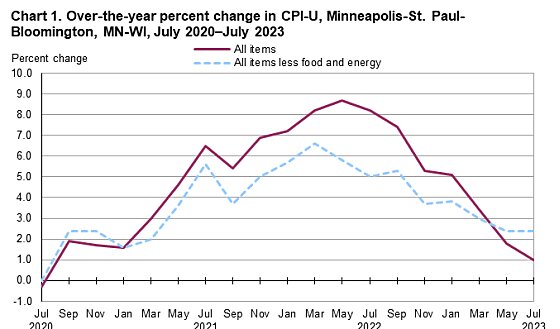

Last week, Maltman’s conclusions gained further support. As detailed in a new Bloomberg analysis, Minneapolis’ housing reforms “helped unleash a boom in construction of apartments and condos in the region that proved to be a powerful antidote against inflation, given that the cost of shelter accounts for more than a third of the overall US consumer-price index.” In May of this year, in fact, the Twin Cities was the first major metro area to have an annual inflation rate below the Federal Reserve’s 2 percent (it hit 1.8 percent), mainly because the annual increase in Minneapolis’ shelter prices were half the rate of the nation overall. The latest Consumer Price Index data show similar things in July, with annual shelter inflation in the Minneapolis area at 4 percent, versus 7.7 percent for the all major urban areas (which the Bureau of Labor Statistics says accounted for more than 90 percent of the monthly CPI increase). Thus, while annual inflation in the United States was still more than 3 percent, it was just 1 percent in Minneapolis:

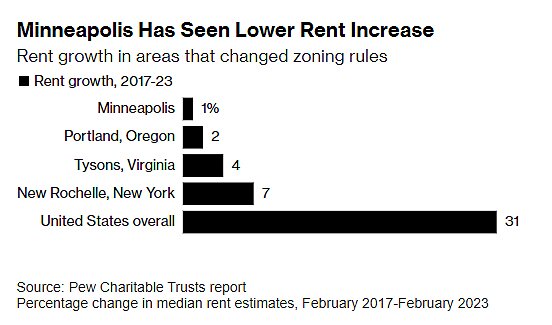

As Bloomberg details, zoning deregulation was key to the area’s housing cost moderation: Rent growth in both Minneapolis and other places that have deregulated zoning is far below rent growth in the rest of the country.

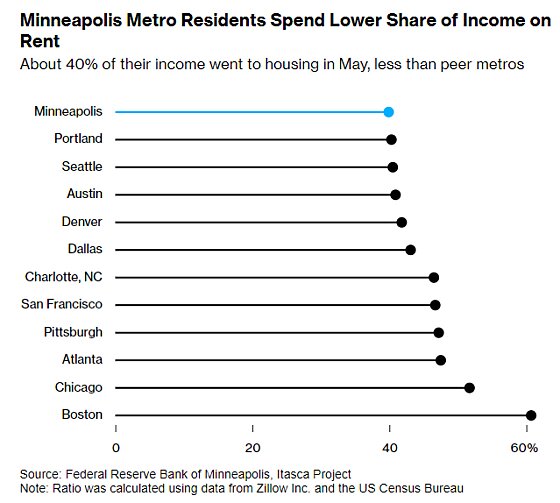

Minneapolis residents today also spend less of their incomes on rent than do residents of comparable metros around the country:

The article goes on to quote local officials, experts, and housing advocates all singing the same tune, which is right in line with the economics research: Controlling housing costs is critical to a city’s growth; the way to control costs is to boost housing supply; and critical to boosting housing supply is land use deregulation. Minneapolis Mayor Jacob Frey put it best: “I can’t tell you how many people were like, ‘Oh, look at all this supply, look at all these just brand new buildings,’ and kind of scoffing at it like this was going to lead to gentrification or rents skyrocketing. The exact opposite has happened.” Huzzah.

Amazingly enough, the results in the Twin Cities probably would’ve been even better if St. Paul, which is in the same statistical area as Minneapolis but subject to different local housing policy, would have followed Minneapolis’ lead instead of foolishly experimenting with rent control last year. As Bourne explains, rent controls that don’t bite (e.g., because they set prices above market rates or don’t apply broadly) might do minimal economic damage, but—

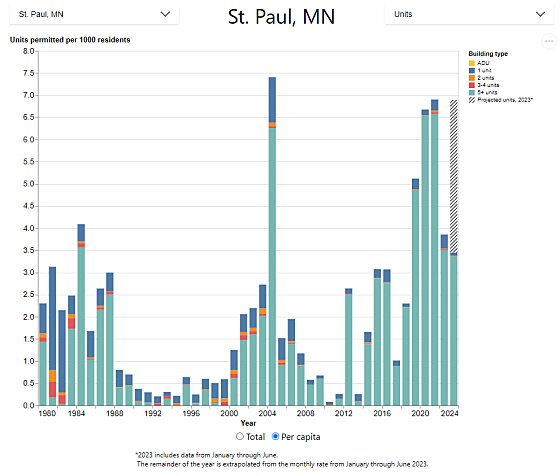

Under cruder, more pervasive rent controls, new building of rental accommodation can collapse quickly. In 2021, St. Paul, Minnesota approved a stringent rent stabilization ballot measure that capped rent increases at three percent per year, regardless of inflation. Immediately, new multi-family building permits plummeted 80 percent, while increasing almost 70 percent in neighboring Minneapolis. The city council thus rowed back on the ordinance to exempt newly-built units from controls, creating a class of rentable accommodation not subject to the regulations.

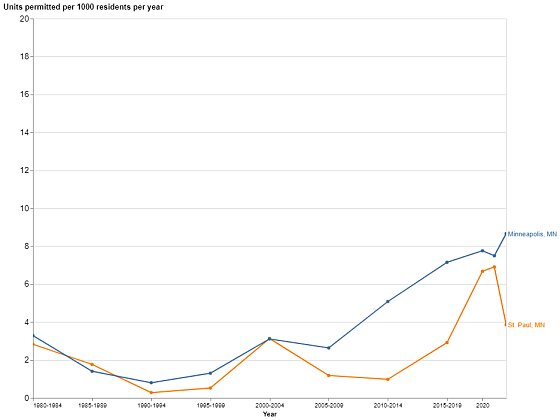

We now have more data on building permits in both the Twin Cities, and the 2022–2023 results are stark. Before last year, residential construction permitting generally followed the same trends; in 2022, however, that changed:

Now with the controls loosened in 2023, St. Paul’s multifamily construction is projected to bounce back to pre-controls levels:

The same database also shows, however, that St. Paul has been building more single-family homes and fewer multifamily buildings—especially those “plexes”—than next door Minneapolis. In 2022, for example, more than two-thirds of the buildings permitted in St. Paul were single family homes, while they were less than half of Minneapolis’ permits. The former also had almost no plexes, while the latter had several dozen.

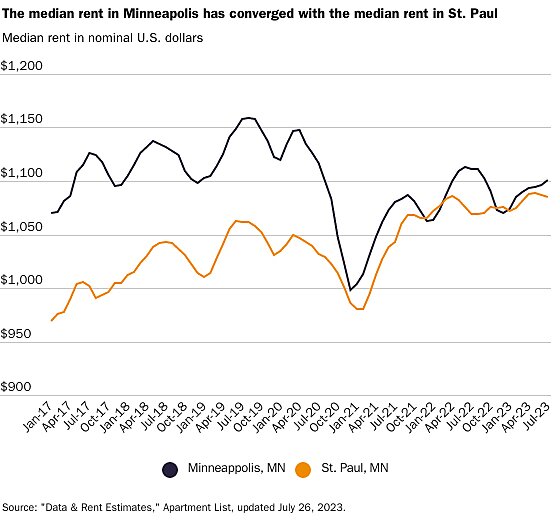

Rents in the two cities appear to reflect these building trends. In St. Paul, rents moderated a bit last year but are still well above where they were a few years ago. Because Minneapolis rents have—as noted —actually declined over the same period, what was once a big premium for living there over St. Paul has now basically disappeared:

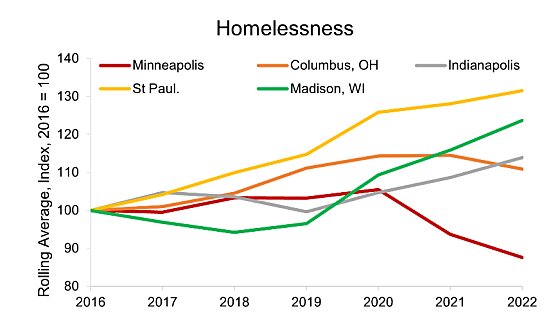

Homelessness trends, via Maltman, have also diverged:

Again, there are a lot of factors at play here—and I look forward to more rigorous analyses of these and other data in the coming months. But you don’t really need an econ PhD to realize the trends here: Allowing market-rate housing supply to meet growing housing demand will help tame prices (and maybe even lower them), and will do so without messy, counterproductive government price regulations.

Gravity, it turns out, still exists.

(In Minnesota, at least.)

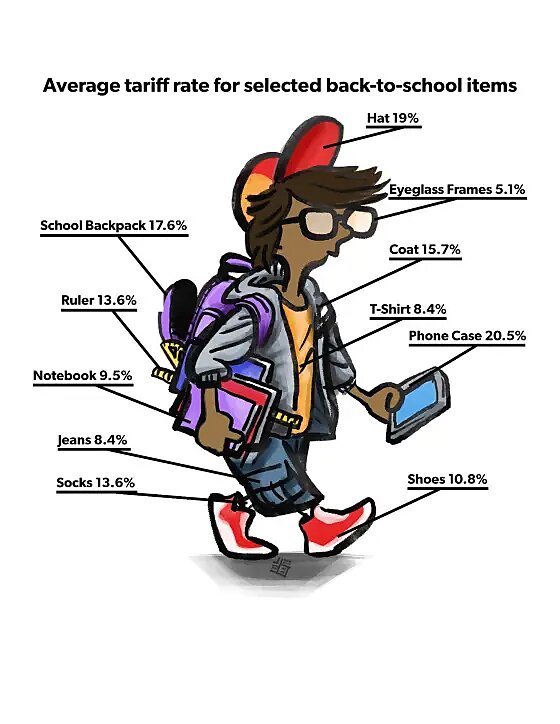

Chart of the Week