Dear Capitolisters,

Now that the midterms are (mostly) behind us, folks in Official Washington have begun the biennial ritual of confidently asserting that the election results confirm whatever the asserter has been saying all along. There are, of course, usually a few people who are either lucky or skilled enough to accurately make such assertions (here’s one), but usually this is just about good ol’ motivated reasoning: People in D.C., especially those who work daily on a specific policy niche, tend to care about that niche and thus—being human and all—have a massive, subconscious incentive to search for evidence “proving” that their issue did indeed justify any and all political results.

I work hard to avoid this trap—voters are complicated, myriad factors (big, small, rational, emotional, national, local, etc.) drive their votes, and simple stories are rarely, if ever, correct. But I admit to caving to my biases this year, as I just kinda assumed that the election results would, as usual, reflect the economic data and polls that we discussed last week. A week removed from the election, it’s safe to say that I assumed incorrectly.

Other folks, however, are sticking to their guns, despite a wave (umm, flood?) of evidence to the contrary. One such claim that I’ve seen repeatedly is the notion that the massive fiscal stimulus enacted since President Biden took office—primarily in the form of the $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan but also the infrastructure and industrial policy spending too—wasn’t just outweighed by other, non-economic issues but actually a big tailwind for the Democrats this year. Thus, apparently, 2022 was an always-spend-more lesson for the already always-spend-big party.

The main “proof” of this claim, unsurprisingly offered by people who typically advocate for more government spending, is that Obama’s Democrats got shellacked in 2010 because (supposedly) they “lowballed” their post-Great Recession stimulus package, while no such drubbing materialized this time around because (again supposedly!) Biden went big with the ARP and the rest of his cash-firehose agenda. But is that a proper comparison, and is this really the lesson we should draw from last week’s elections?

No and no.

A Good Comparison Needs a Good Comparator

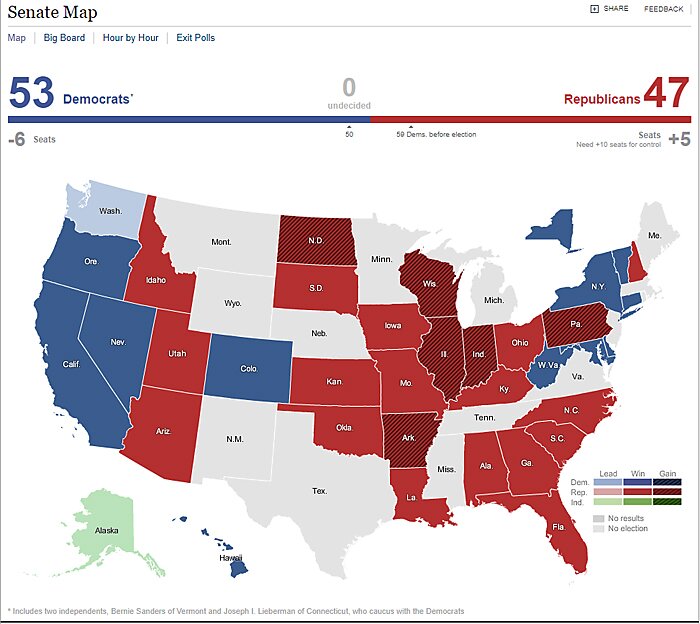

First, from both a political and economic perspective, 2010 was almost nothing like 2022. Yes, both midterm years share the same Senate map and follow a big recession, but that’s where the similarities stop. Politically, the very-plugged-in Liam Donovan reminds us that big Republican gains in 2010 consisted of a lot of low-hanging fruit: Because they got absolutely crushed in previous elections, the GOP held only 41 Senate seats and 178 House seats going into the 2010 midterms. Thus, the 2010 “wave” election got Republicans a whopping … 47 seat minority in the Senate:

In 2022, by contrast, the GOP held 50 and 212 seats, respectively—meaning that a “red wave” matching 2010’s sheer numbers (six Senate and 63 House pickups) was, thanks to the country’s longstanding partisan divides, all but impossible. The map also meant that Democrats were defending far fewer up-for-grabs seats this year than they were in 2010, so they could allocate more money to exposed incumbents (who already have built-in advantages). And, hoo boy, did they allocate.

Compounding the political trouble in 2010 was the highly controversial Obamacare, which estimates show was directly responsible for picking off several Democratic House seats (as even many Democrats later admitted). Biden’s Democrats had no such political target on their backs in 2022—especially since they responded to Americans’ big inflationary fears with the (ridiculously named, but perhaps politically effective) “Inflation Reduction Act” and, as my colleague Ryan Bourne documented last week, Americans don’t really know where inflation comes from.

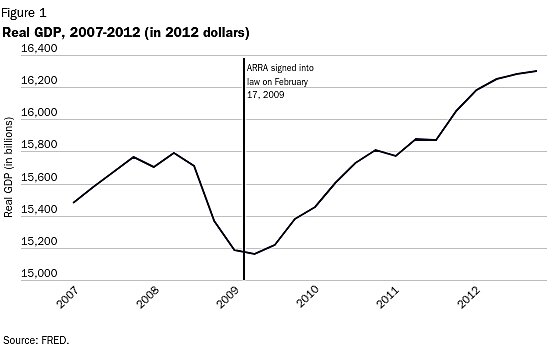

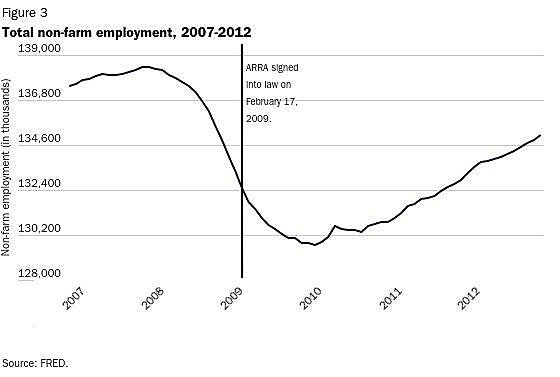

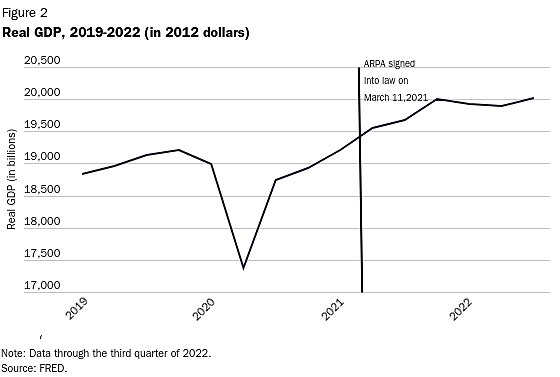

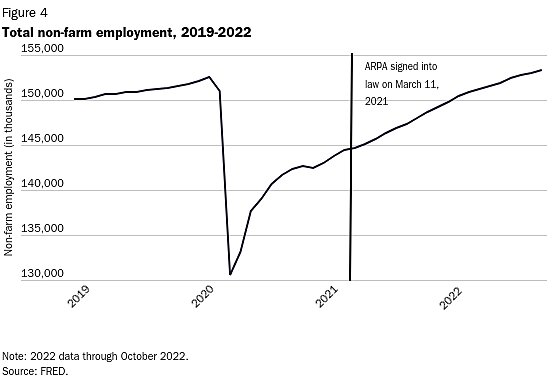

The economic gulf between 2010 and 2022 was also massive, mainly because the recessions that preceded those midterms were radically different. Scores of economic studies on past recessions show that financial crises are deep, prolonged, and costly, often producing “U shaped” recoveries in which output and employment bottom out, stay there for a while, and then only recover many months later. Pandemic recessions, by contrast, are usually “V shaped,” meaning that output and employment collapse but then quickly snap back to normal (or almost normal). As we’ll see in a second, both the Great Recession and the pandemic recession hewed pretty closely to economic type, with the former slow-burning through the U.S. economy for several years while the latter flamed up and out within several months. Other big differences include the fact that, unlike the 2008-09 financial crisis, much of the pandemic’s economic pain was self-induced (via government lockdowns, business closures, etc.) and could therefore be “flipped off” when virus conditions improved, and that the Great Recession—again owing mainly to the nature of the financial crisis—significantly eroded Americans’ wealth (in the housing and stock markets), while the pandemic era saw much the opposite.

One can plausibly argue, I think, that the U.S. policy response to the Great Recession was in retrospect too limited. Reasonable minds can differ there. But that doesn’t necessarily mean the episode provides a lot of good policy lessons for 2021. The data show, in fact, that it’s very much an apples-and-oranges situation.

Memory Holing 2021

This gets to the second issue with the spend-more thesis: the timing of Biden’s stimulus, especially versus Obama’s. Regarding the former, the Great Recession was still working its way through the economy in February 2009 when the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act became law.

By contrast, and as I documented on these pages in February 2021, the economic situation that Biden inherited was clearly and rapidly improving; Americans’ personal finances were in very good shape (thanks to both forced saving and previous government support); and the future—vaccines proliferating, localities reopening, etc.—gave us plenty of reasons for optimism (excepting certain customer-facing services and continued pandemic cloudiness). Thus:

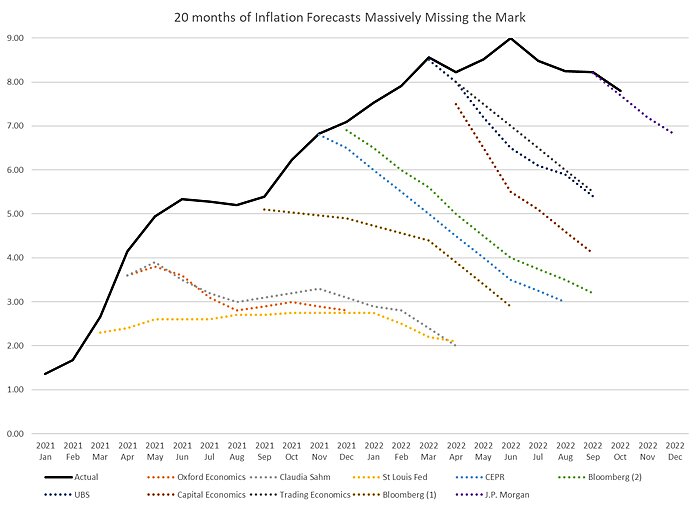

The Atlanta Fed’s GDP Now tracker, which incorporates various economic releases in real time, currently projects first quarter GDP growth to hit 9.5 percent, and the bond market is now indicating that the U.S. economy is recovering far more quickly than many experts expected only a few weeks ago. While the GDP Now figure will probably shrink when new data comes in, other forecasts for the first quarter—from Goldman Sachs (6 percent), Morgan Stanley (7.5 percent), and JP Morgan (5 percent)—are also sanguine, and Bank of America has now raised its full-year 2021 GDP projection to a blistering-hot 6.5 percent. JPMorgan further reports that the United States could “out-rebound” China in 2021 and beyond.

After looking at other data on jobs, trade, business formation, regional growth, and so on, I concluded back then that, while some hurdles and wobbles would inevitably arise in 2021, “it’s still quite clear that the nation’s economic despair is in the rearview mirror.” And it was:

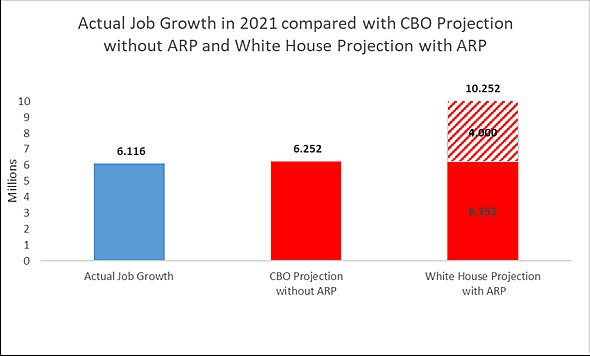

I certainly wasn’t the only one who noticed the positive economic trend, either. As AEI’s Matt Weidinger just recently documented, for example, nonpartisan experts at the Congressional Budget Office “predicted historic job creation even without any of the administration’s trillion-dollar spending plans, as the economy continued to recover from massive pandemic layoffs.”

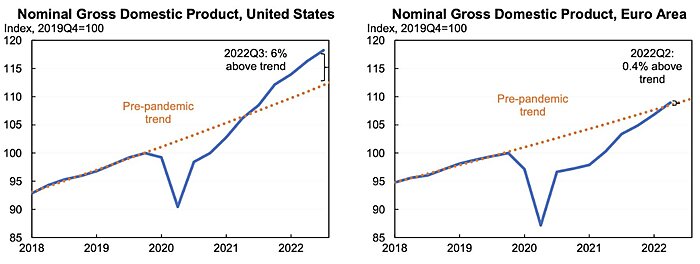

This already rosy situation, not mass unemployment at the depths of the Great Recession (or worse), provides us with the proper counterfactual for gauging the political efficacy of Democrats’ spending, which was more “bonus cash” than some sort of essential economic lifeline. Thus the proper question isn’t whether voters would’ve voted blue in the middle of a depression, but whether their motivations would’ve differed much in a U.S. economy with, per the early/mid-2021 projections, a little more unemployment but—more like pre-Ukraine Europe—a little less inflation and recession uncertainty. And even if you assume that all that stimulus spending really did juice growth and jobs (Federal Reserve policy notwithstanding), was that juice—boosting nominal GDP well above pre-pandemic trends—really worth the inflationary squeeze?

Color me skeptical.

Shovel Ready?

Third, there’s the actual timing and effect of all that spending. As Weidinger notes, for example, $1.2 trillion of the ARP’s $1.9 trillion was spent in 2021 (i.e., 11 months before the midterms), and Democrats failed to extend temporary social spending programs like the child tax credit (leading to, as always, the usual bleating about heartlessly throwing Americans back into poverty in 2022). Subsequent spending, such as on infrastructure and semiconductors, has trickled out slowly, as federal procurement (unfortunately) always does. Just a week ago, for example, Politico’s deep dive showed that “nearly a year after President Joe Biden signed the biggest infrastructure bill in decades, decisions about how to spend all that money are just getting underway. And his party is struggling to reap the electoral rewards.” Funds for semiconductors, on the other hand, won’t actually be disbursed until next year, and the ink is barely dry on the Inflation Reduction Act.

One might argue that it was the signing ceremonies, clever legislative names, and related political fanfare that psychologically motivated voters or assuaged their economic fears, but that’s pretty impossible to suss out in the numbers (people think the economy stinks!), and it’s a far different argument from saying that the actual effects of fiscal stimulus are what boosted Democrats’ political fortunes.

Yet here we are.

And Then There Are the Exit Polls

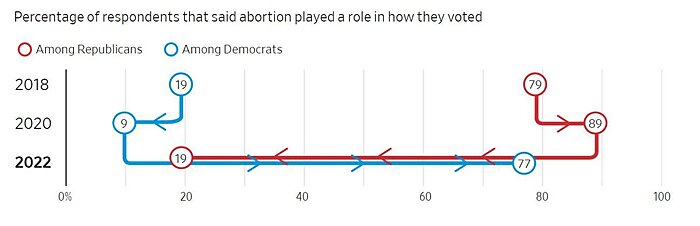

Finally, there’s the simple problem of the mountain of evidence pointing to non-economic factors driving most of the 2022 midterm results. For example, Will Saletan just looked at a massive batch of detailed exit polling data and found that the Dobbs decision that returned the abortion issue to elected officials was a major driver of not just how people voted (candidates and referenda), but also whether they turned out to vote at all. In a flip from 2018 (see chart below), the gaps in voter motivation and enthusiasm heavily favored pro-choice Democrats (by 35 points on average, and even larger in certain key states like Nevada), and the issue even appears to have pushed a small but influential batch of Republican “defectors” in Pennsylvania and Arizona to vote for Senate candidates John Fetterman and Mark Kelly, respectively.

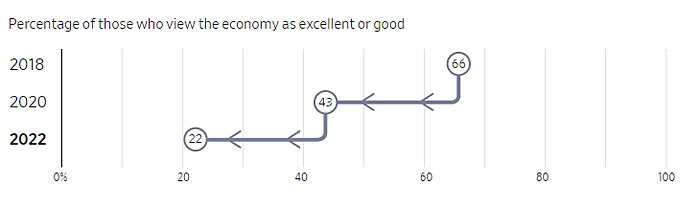

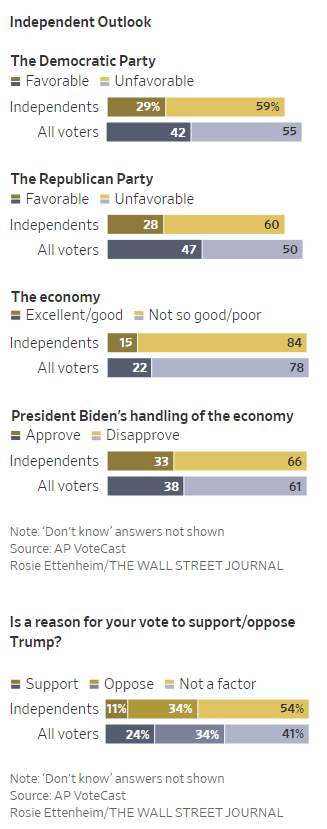

The same data, by the way, also show that only 22 percent of respondents viewed the economy as excellent or good—down almost 20 percentage points since mid-2020. They just weren’t voting on it.

The other big non-economic issues were Donald Trump and, relatedly, candidate quality. The folks at FiveThirtyEight saw the latter clearly in the widespread ticket-splitting across the country:

As Vox’s Andrew Prokop just put it, “The GOP had terrible Senate candidates and it really did sink them.”

The subsequent Arizona results, in which Republicans picked up a House seat but—thanks to Trump-backed Blake Masters and Kari Lake—lost the Senate and governorship, respectively, really drove this home (especially when compared to Republican Gov. Doug Ducey’s romp in 2018).

Semi-final numbers, accounting for uncontested races:

— Yesh Ginsburg (@yesh222) November 15, 2022

GOP Congressional candidates in Arizona: +6.3%

Kari Lake ran 7.1% behind Arizona Republicans. Blake Masters ran 11.4% behind AZ Republicans.

Kimberly Yee ran 4.9% ahead of AZ Republicans.

Yee ran 16.3% ahead of Masters.

Other analyses show similar things: Voters across the country—especially independents—appear to be increasingly repulsed by MAGA, Trump, and his gang of goofy rigged-election wannabes, and they voted for Democrats despite the economy, not because of it.

By contrast, as Decision Desk’s Derek Willis notes, many winning Republicans ignored the Trump circus altogether. National Review’s politicians guru, Jim Geraghty, summarized the situation well: “To win in once-purple, now-blue places such as Colorado, Republicans will need to shed the albatross of Trump and broaden their appeal even further. The national exit-poll numbers [on inflation and the economy] tell a story of a minority party that was poised to win big if it could just not be perceived as insane. … Yet independents—31 percent of the electorate this year—narrowly split in favor of Democrats, 49 percent to 47 percent.”

None of this screams, “See, the stimulus worked!”

Summing It All Up

As someone who tends to obsess over arcane policy issues, I totally get the urge to look at an election result and see a glorious vindication of my priors. Sometimes, that urge can even be right. But the idea that the surprising 2022 results provide a valuable lesson about the need to “go big” on fiscal stimulus to avoid a 2010-style shellacking ignores history, reality, and an ever-growing boatload of pre- and post-election polling. It even ignores all of the pre-election recriminations and behind-the-scenes reports of Biden and other Democrats regretting their big fiscal stimulus adventures, because—as we noted last week—the folks who were voting on the economy this year probably weren’t pulling the blue lever.

It turns out, however, that a substantial (and in many cases decisive) share of the electorate voted on things other than the economy. That’s the real lesson of 2022… as much as it pains this economics nerd to admit it.

Chart(s) of the Week