As folks around here surely know by now, I tend to be an optimist about the ability of relatively free markets and free people to produce society-wide abundance over the long term. I’ve written at length about how pervasive economic doomerism in Washington systematically ignores decades-long trends in American wages and inequality and living standards and growth and industry and so on and so on. One thing I haven’t discussed, however, is why many normal Americans—not the Beltway planners incentivized to find doom everywhere—share in this economic pessimism. And since it’s still August and a few commenters have asked about this very thing, now’s a perfect time to dig in.

Why We Worry

Surely, a lot of things—the obvious allure of quick, easy, tradeoff-free solutions to complex problems, widespread innumeracy and other educational challenges, our tendency to treat powerful-but-isolated anecdotes as national data, and quite real and often-scary disruptions to our daily lives (especially over the last two years)—contribute to pervasive American pessimism about markets and the economy. For my money, however, three others stand out:

First, market gains are typically slow, incremental, and messy—causing us to ignore or even mock new products and services when they first debut. Private companies in a competitive (mostly) global environment are always looking for tiny ways that they can improve the consumer experience and thus keep or win our business. This search leads to a ceaseless process of trial and error, with numerous failures and (less often) successes over time. Economist Diedre McCloskey notes in her new book, for example, “The stocking of US grocery stores evolves through the supplying and the demanding of 30,000 or 40,000 new packaged consumer goods every year, under one percent of which become regular items.” And we’re mostly oblivious to it all.

Successes, moreover, typically happen on the margins, as opposed to being radical and instantaneously life-changing innovations. Those tiny improvements seem insignificant in the moment, but over time they can really add up: There may be little noticeable difference between version 1.0 and version 1.1 of some product, but the difference between 1.0 and 5.0 is pretty incredible.

We consumers acknowledge these updates a bit when it comes to certain things like cars or electronics—annual iPhone or gaming system debuts often receive headlines—but they’re happening everywhere all the time, and they’re mostly ignored. Indeed, the only time people seem to notice the slow, gradual improvement in most goods and services is when we’re forced to utilize their now-seemingly-prehistoric versions 1 or 2. Suddenly, the Good Ol’ Days don’t look so good.

I had this very experience just a few weeks ago (part of the inspiration for this column), when I found myself in a hotel bathroom without my nothing-special five-blade razor and was forced to use the single-blade disposable thing that the hotel kindly gave me. It was a totally miserable experience: nicks, missed spots, irritation, you name it. Blech. My boring razor was suddenly a modern marvel—even though it once was famously and hilariously mocked by The Onion as a preposterous gimmick (because three blades had just become the new, and obviously-more-than-sufficient, normal). Today, you can get generic five-blade razors—and all sorts of other gizmos—basically anywhere (and for cheap), while six- or even seven-blade gadgets are also now a thing. The slow, unnoticed march of razor progress continues apace.

Shaving science, of course, isn’t the only feature of daily life benefiting from constant, incremental innovation. Even leaving aside our pocket supercomputers and related gizmos (or the constant free updates to our ever-growing app universe), you find similar improvements across a wide spectrum of goods and services, from the marvelous to the mundane:

JUST LOOK AT ALL THIS TECHNOLOGY AND WE NEVER TALK ABOUT IT pic.twitter.com/LzRzfLwP42

— Scott Lincicome (@scottlincicome) August 7, 2022

And, aside from too-online lunatics like me, nobody ever really notices.

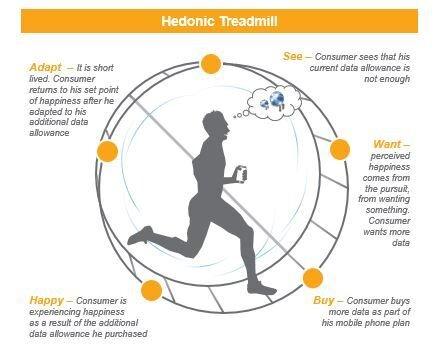

Second, humans are naturally predisposed to becoming numb to the mind-bending abundance that decades of free(ish) market capitalism have produced. Psychology calls this widely observed phenomenon “hedonic adaptation” or the “hedonic treadmill,” in which humans “quickly return to a relatively stable level of happiness despite major positive or negative events or life changes.” Thus, “as a person makes more money, expectations and desires rise in tandem, which results in no permanent gain in happiness.”

The same goes for living standards and wealth, and free marketers routinely discuss the hedonic treadmill when trying to figure out why, when everything is so historically great, so many adults always seem miserable. (Kids can be forgiven—they don’t remember what it was like to have only five TV channels, maybe six if the rabbit ears were perfectly situated.) In short, we rapidly adapt to our new, relatively amazing normal, yearn for even better thereafter, and, of course, loudly complain when a relatively minor glitch in the new normal occurs:

It's been like this for 45 mins, @hulu @hulu_support #DALvsTB pic.twitter.com/9URAuwIBfQ

— Scott Lincicome (@scottlincicome) September 10, 2021

(Yes, there’s a brilliant and hilarious comedy bit about all of this, but I’m afraid it’s been canceled or something. So don’t click that or laugh at it, or else you’re in really big trouble.)

The pandemic revealed our “hedonic treadmill biases” over and over again. Yes, of course, there were some real catastrophes out there. But a lot of the wailing and gnashing was just hedonic adaptation doing its thing: Americans accustomed to free two-day shipping from the Everything Store or store shelves always full of 97 different types of cereal called momentary lapses in those (and many other) modern luxuries a “crisis of capitalism” and other silly things—ignoring, as always, that these “necessities” didn’t even exist a few years ago (and still don’t in much of the world, even in normal times). That the hedonic treadmill doesn’t work the same for positive and negative events—we tend more to memory-hole the former and emphasize the latter—also helps to explain why almost everyone remembers (and writes about) those few weeks of empty store shelves yet basically ignores them all being full again.

People were even seriously calling 2021 the “worst year ever”—ignoring not only terrible previous eras but also the very previous year (which was obviously far worse). As the Washington Post’s Megan McArdle astutely observed last year, those and other laments were blind to the simple and obvious fact that life would’ve been worse—much, much worse—if the pandemic had occurred just two decades ago when remote work, e-commerce, and, of course, mRNA vaccines were much less developed:

Even a short time ago, more of us would have gotten sick, more of us would have lost loved ones, and, quite possibly, more of us would have lost businesses and jobs. The pandemic has been awful, and the toll too terrible for words. But it’s also true that we avoided much suffering — and just how much should stun us into silence every time we think about it.

Yet how often do we think about that, compared with how often we get angry at the people we believe are pandemic-ing wrong? For that matter, how often do we wonder at any of our chronological good fortune? Long before the pandemic, we routinely lambasted, say, our cable provider for poor customer service, and rarely congratulated them for selling us hundreds of channels worth of entertainment; we crabbed about cramped seats, long security lines and terrible food instead of thinking about how extraordinary it is that our ancestors bequeathed us the gift of flight. That’s human nature, of course: No matter how good our luck is, we get used to it, and trudge forward on the hedonic treadmill, as miserable as we ever were.

As I’ve written a few times now, things today might seem rough when you compare them to yesterday—a comparison that our age of conspicuous internet consumption surely distorts or amplifies—but they’re almost always really good when you compare them to a couple decades ago. And they’re really, insanely great when you go back even further.

But we’re just not hardwired to do that.

Finally, there’s an intense incentive among politicians, certain policy wonks, and the media to downplay progress in order to sell their products (policies, pageviews, etc.). AEI’s Scott Winship put this perfectly a few years ago when explaining why everyone thinks wages are stagnant when, as he showed, they’re really not:

There is also the reality that many parties in Washington and many outside parties interested in influencing Washington have biases in favor of analyses that convey gloomier news. Advocates and politicians on the left want to promote agendas that involve redistribution and more government intervention into markets. Politicians on the right, meanwhile, must tend to middle class anxieties (and most of these policymakers mistakenly believe, along with other Americans, that our problems are worse than they appear). Policymakers from both parties have an interest in painting a dour picture of the economy when their opponents are in power.

Meanwhile, academic and policy researchers on the left often believe that economic problems are relatively great, and so results that reinforce the view that we have calamitous problems help generate support for their preferred policies. Researchers across the ideological spectrum—and their institutions and funders—want to attract attention, which creates a bias in favor of more dramatic results. And journalists are largely left-leaning*, making them predisposed to believe gloomy economic news, eager to help people in need through their writing, and disproportionately likely to have relationships with left-leaning researchers producing work that corresponds with their priors. Even moderate and conservative journalists face pressures to find and report on dramatic results; if it bleeds it leads. Finally, the spread of overly gloomy results to policymakers, consumers of news, and citizens tend to give people the impression that things are worse than they are, reinforcing many of the dynamics that incentivize gloomy news in the first place. People are generally more pessimistic and negative in polling that asks about the economic problems of others than they are when asked about their own economic situation.

These are powerful forces working against knowledge of the state of our living standards.

Indeed, they are. (And see fellow Dispatcher Chris Stirewalt’s latest for more on the media incentives.)

And That, Naturally, Brings Us to … Eggs

Add these three factors up, and—even leaving aside those others I mentioned up front—the deck is seriously stacked against limited government, free market optimism. Doom sells, and there are a lot of eager salesmen. Never mind, as Stirewalt puts it, that “things are so much better here and now than they’ve been for most of human existence: freer, richer, safer, cleaner, and easier.” Or that we keep seeing markets recover, innovations bloom, and alternative, more regulated approaches—ahem, rapid tests and baby formula autarky—cause even bigger problems than the endless ones our political saviors promise to fix (right after the next election).

I’ve noted plenty of these examples over the last two years, but here’s one more: eggs (no, really). As you may recall from the spring, a major outbreak of bird flu in the United States resulted in the preventative culling of tens of millions of egg-laying chickens and thus threatening domestic egg supplies because we source almost all of our eggs domestically. Thus hatched (sorry) myriad scary articles warning of serious egg shortages over the summer. As I tweeted in May, however, there was reason for optimism that a worst-case situation could be avoided because we have a relatively free and open egg market that would probably adjust to prevent the persistent and wide-scale shortages we saw with baby formula:

Fortunately, we allow egg imports (eg, low tariffs) so store shelves should remain OK without any “emergency” government actions. (Unlike, say, formula.) I’m fact, the last time (2015) bird flu hit the US, imports increased a lot to fill 5he gap. Resiliency! https://t.co/pWRSMoC95N pic.twitter.com/eLBIpXksnD

— Scott Lincicome (@scottlincicome) May 25, 2022

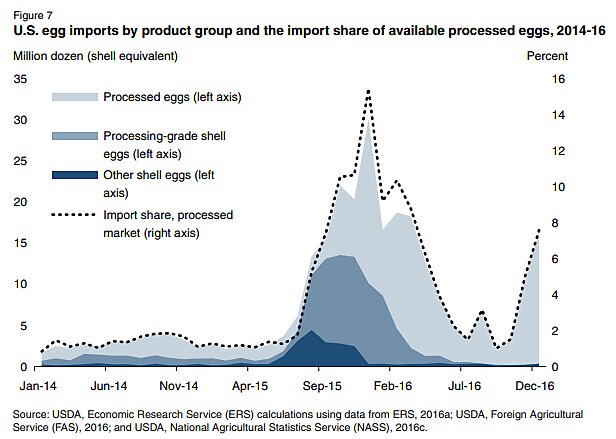

A 2017 USDA report supports my armchair analysis, documenting how private parties—relatively unencumbered by government barriers (tariffs, price controls, etc.)—prevented major problems during the last U.S. bird flu outbreak in 2015–16. In short, domestic egg supplies collapsed; egg prices rose; foreign egg producers entered the market in response (a “very large increase in imports”); and American grocers restocked their shelves. Breakfast was saved.

The same things appear to have happened this time around. Prices again increased, and imports predictably surged (albeit to an apparently smaller degree than 2015–16):

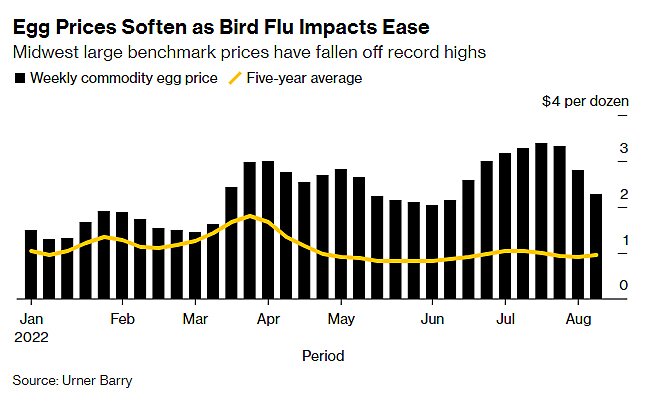

Isolated issues surely popped up over the summer, but widespread, long-lasting egg shortages—and months of empty shelves of the infant formula variety—were avoided. Now, prices are “falling fast” as bird flu cases disappear and American hens start producing again:

As happened countless times during the pandemic, the market and our much-maligned supply chains (and, of course, those evil grocery oligarchs) appear to have worked. The president didn’t need to commission C130s to fly in eggs from Germany. Congress didn’t need to pass emergency egg legislation. I didn’t need to write 17 columns about the problem. All we needed to do was go about our daily lives and stay out of the way.

No wonder nobody noticed.

Chart(s) of the Week

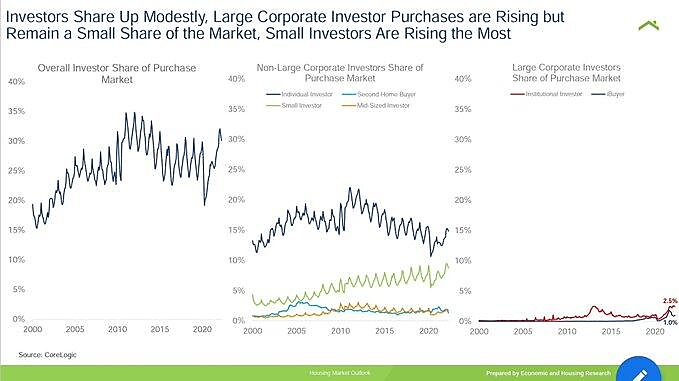

Large institutional investors are still only 2.5 percent of the U.S. housing purchase market:

Here’s a library of useful Medicaid charts, including this one:

The Links

Canceling student debt is a terrible idea

Cato’s Ryan Bourne debunks the myth of World War II price controls

“Caring for Small Children Does Not Require a College Degree”

Used car deflation coming soon?

Policies that increase the cost of necessities are anti-family.

U.S. retailers have bloated inventories

New paper: How “Buy America” laws can undermine national security

“The CHIPS Act won’t end US reliance on foreign foundries”

Some more problems with IRS funding

“Remote Work Is Sticking,” says the New York Fed

New York is so desperate for fuel that it’s using Jones Act ships

The precautionary principle—here, an EU ban on drought-resistant GMOs—claims another victim

Zillow: 780 of 911 U.S. housing markets will still see home price increases over the next year

U.S. remote workers flock to Mexico City

“California Needs More Housing. Unions Might Stand in the Way.”

Arizona expands “right to try”

Eminent domain run amok in North Carolina (to implement industrial policy, of course) (more)

J.P. Morgan’s notes on China’s “Japan-style” housing downturn

China demolishing brand new buildings?