So, one of the things I’ve been tracking closely of late is the U.S. Congress’s war on “Big Tech.” The most recent salvo in the Senate, led by the neo-trustbuster Senator Amy Klobuchar, is a revised bill that could make Google and Meta pay news websites to “access the content” of digital journalism providers.

This version of the Journalism Competition and Preservation Act (JCPA) works by carving-out antitrust (competition law) exemptions for news sites, such that they can band together, or cartelize, to collectively demand payments from major digital platforms for using links to, or snippets of, their publications.

This “link tax,” as similar laws in Australia and several EU countries have been known, is predicated on the idea that Google and Meta are destroying local newspapers and independent journalism, and that these journalism providers should be granted a share of the Big Tech spoils in recompense for their content.

The bill’s sponsors sell it very much as a lifeline for “small, local, independent and conservative news publications,” given the law would not apply to network broadcasters or big digital news companies with more than 1,500 employees, such as the New York Times or Washington Post.

And, on that, they are unintentionally revealing. The closer you look at the bill, the less it seems like a neutral mechanism for a genuine negotiation in value exchange, and the more it looks like a hidden tax and subsidy policy — an industrial policy for smaller news outlets, as it were. That, though, raises the question: why even pretend this is anything to do with antitrust or ensuring open competition? This is about politicians taking money from businesses they don’t like and giving it to companies they consider virtuous. The method they use just keeps this redistribution off the government’s books.

What the bill does

The JCPA, in effect, creates something like a property right for eligible news websites’ content. It develops a process framework that allows news sites and non-network broadcasters to demand a negotiation of “terms and conditions” with Google and Meta for, one assumes, linking to or previewing their content.

Eligible content — i.e. what we’d just call journalism — is defined quite broadly, so we can expect a lot of legal uncertainty here. But the point is, the bill develops a route for digital journalism providers to, in principle, form joint negotiating entities to demand cash from platforms like Google and Meta for linking to their work. The digital platforms are expected to participate in these negotiations, and if the news outlets aren’t satisfied with the outcome or offers from such talks after 6 months, they can demand a final and binding arbitration of the dispute.

A freer market?

Now, given I’m skeptical about antitrust laws per se, my first reaction to this was ambivalence. In a completely free market, it might be natural for news outlets to collectively bargain as a defensive strategy. Google, Meta, or other covered platforms might well be willing to stump up if they think these sites’ contents help draw people to their platform network by improving their search or user experience. So, one might assume that chipping away at antitrust laws through an exemption actually takes us closer to free negotiations. Hence, I suspect, why the bill has won the support of the libertarian Senator Rand Paul.

But in a genuinely free market, news outlets taking such action would also face the risk that the digital platforms would just say “oh well, we’ll just stop listing your content.” That countervailing power, though, is curtailed under this legislation.

Indeed, this bill is not neutral on how the parties negotiate these value exchange tensions. Both must put forward their proposed “terms and conditions” estimating a “fair market value” for the digital platform accessing news content, for example, considering any advertising or promotional revenues that links or preview content of news sites helps Google or Meta to obtain.

Yet the bill explicitly compels both negotiators and even arbitrators to ignore any value conferred to digital journalism providers from being aggregated or distributed by the tech giants. In other words, the advantages to Google from hosting previews to The Columbus Dispatchshould be considered in working out how much is owed to the latter, but any value to The Columbus Dispatch of being listed or previewed on Google News or Facebook must be ignored.

If a media company demands payment for accessing their output, in fact, platforms like Google and Meta are specifically barred from retaliating against the former’s content. These clauses were no doubt formulated by lawmakers cognizant of Australia’s experience, where a similar law saw Meta block news articles being shared for a few days to try to avoid its effects. Google likewise shut down its Google News service in Spain for eight years to avoid paying a link tax.

Fearful of similar treatment being meted out to individual digital journalism providers as part of the negotiations, this bill would therefore disable digital platforms from “refusing to index content,” or from “changing the ranking, identification, modification, branding, or placement” of the news websites’ content.

Given the sensitivities of search engines and algorithms, such actions would no doubt be difficult to prove in court, especially for smaller outlets. [This, by the way, is one reason why the legislation will unavoidably benefit the biggest firms that are eligible]. But the legal risks of retaliation makes this process something much closer to a forced negotiation for Google and Meta.

It’s really an industrial policy

So, no, this legislation doesn’t liberalize negotiations from the shackles of antitrust. It instead delivers a special, one-sided carve out from current law to the financial benefit of a specific industry. For not only are Google and Meta given few routes out if news sites come asking for cash, but the option of seeking that cash is only available to digital journalism providers, not other content producers.

As Benedict Evans asked last year: What is the justification for separating news outlets from other websites for the purposes of being paid for links or previews? If Google and Meta linked or previewed the Cato Institute’s output, then why can’t we negotiate an appropriate payment? The answer to the first cannot be that there’s some fundamental power imbalance between digital platforms and digital journalism. If that were the reason, many other types of output would have a much better claim against Google and Meta in regard to “access” of their content than newspaper websites.

No, the fact that the legislators single out news publishers is because they think there’s something inherently valuable about digital journalism and they want to be seen to punish Google and Meta for their role in disrupting the traditional newspaper sector. They want to give online journalism more money — by forcing Google and Meta to pay for it. What this really amounts to, then, is a tax on certain companies deemed to have hurt local newspapers to, in effect, subsidize the new digital variants of those traditional papers and non-network broadcasters.

It isn’t a policy aimed at levelling the playing field for competition or solving a market failure. It’s politicians telling us what they think is good for society and transferring resources to their preferred sector.

The wrong boogeyman?

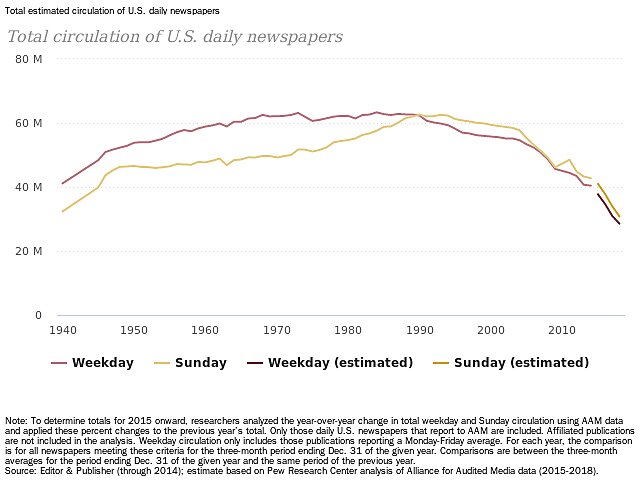

In reality, of course, it wasn’t inherently Google and Meta that squeezed local papers. It was the internet. As the figure below shows, newspaper circulation has been falling since the 1990s, coinciding with the world wide web’s advent. Local newspapers, in particular, used to roll-up local news, sports, investigative journalism, company adverts, dating adverts, and opinion pieces together. The internet, by allowing each of these to be produced separately to large, targeted audiences, stripped away readers *and* paying advertisers, so unravelling money-spinning content from stuff that was cross-subsidized.

Yes, it’s true, Google and Meta’s more targeted advertising business stripped the newspapers of their major revenue source, and this occurred from the late 2000s when social media platforms really honed better targeting. But that’s just an example of the broader phenomenon of the unbundling that the internet technology facilitated.

Tinder, Hinge, and Match.com would eventually have usurped newspaper dating ads. Specialist sports websites, message boards, and individual club websites allow people to keep track of their local teams. Substack provides edgy opinion pieces. Even in terms of hyperlocal human interest stories, Facebook groups allow people to organize events, warn others of crimes, return lost pets, and form communities of shared interests, while Nextdoor is available for up to 1‑in‑3 U.S. households’ neighborhoods for people to discuss and gossip about what is going on in their area.

Given this content revolution, it’s difficult to see that even guaranteed transfers from Google and Meta would fund output that will get enough eyeballs to run a successful all-singing, all-dancing traditional local newspaper online.

But that’s what the legislation is trying to achieve. Industrial policy is back in Washington. And just as other politicians are keen to revive the heyday of 1960s manufacturing, these co-sponsoring Senators want to try to keep alive the local news outlets of yesteryear with a hidden tax and subsidy regime.

Other things

-

My Times column got a lot of blowback in the comments this week. It was a critique of UK Labour’s proposal to change the Low Pay Commission’s mandate such that living costs were “also” considered when setting the minimum wage. The LPC used to have independence to recommend setting the wage floor at a level that didn’t produce job losses. George Osborne overhauled this, setting a target of 60 percent of median hourly earnings, whatever the effect on jobs. This has since increased to 66 percent. And now Labour seemingly want to double-lock the wage floor for periods where inflation exceeds median earnings growth. The context here is key: the energy price spike means people in the UK are poorer and businesses less productive. It would be crazy to introduce a new provision for the LPC implying that businesses should be forced to set pay according to fuel, rent, and food costs that they do not control, and which policy often worsens, rather than paying workers for their actual jobs.

-

I’ve not really written anything about Joe Biden’s student loan debt forgiveness plan. Just to say here that I’ve been impressed with how some left-wing academic economists have developed imaginative justifications for a policy that, if the same outcomes were delivered through tax cuts, they’d dismiss as fairly regressive. This thread from Arin Dube is my personal favorite. It’s an art, really.

-

EconTalk host Russ Roberts’ new book Wild Problems: A Guide to the Decisions That Define Us is thoughtful on the limitations of cost-benefit analysis in helping one navigate life’s major decisions.

-

My fortnightly UK ConservativeHome column was on fertility and government policy. I happen to think that most of the decline we are seeing across the West in fertility rates stems from free choices. But there remains a UK gap between people’s stated preferences for family size and actual family size, and there’s a bunch of bad policies — on tax, housing, childcare, and regulation — that could conceivably explain at least part of this. Let’s undo those and see where we stand before panicking about population decline?