CBS News aired an interview with Federal Trade Commission chair Lina Khan recently.

It got off to a bad start and then got worse.

Host Lesley Stahl began, “Everywhere you go people are complaining about inflation: voters say it’s their number one issue.”

That much is true.

She then said “Enter trustbuster Lina Khan,” implying that the FTC and its chair could meaningfully affect inflation — which, remember, is a macroeconomic phenomenon driven by too much money growth relative to the growth in output in the economy.

That was the unsound foundation for the rest of the interview: the idea that *inflation* — not just high prices for certain goods — could somehow result from “corporate concentration” or “greedflation” or numerous firms suddenly taking advantage of customers.

This, unfortunately, is the premise behind lots of the bad policy ideas we’ve heard advocated since inflation took off. For if inflation was caused by the exercise of corporate market power, then doesn’t it stand to reason that antitrust enforcement or even price controls will be most effective to get it under control?

Corporate Concentration Can’t Logically Explain Recent Inflation

As Brian Albrecht explains in The War on Prices, it makes little logical sense to hold up U.S. corporate concentration as causing the recent inflation.

First of all, overall measures of corporate concentration didn’t obviously increase before or during the period when inflation took off (in fact, we don’t even have all the data yet). And economists have known for decades, in any case, that industry-level concentration measures are terrible proxies for what might affect the price level: broad trends in market power. [Not least because high concentration can reflect a small number of firms providing products perceived to be far better than their rivals.]

But let’s suppose that high corporate concentration was synonymous with market power and that this had somehow increased across much of the economy at the same time. How would changing market power drive economy-wide inflation? Well, firms with monopoly power can charge higher prices by restricting their output. A pervasive growth in market power could therefore theoretically drive up the price level and so, temporarily, inflation, by slowing the growth of real output as a whole. Assuming a constant growth in the money supply and a steady growth in money velocity, a slower growth in real output would mean money in circulation chasing fewer goods, leading to a burst of inflation as product prices increased.

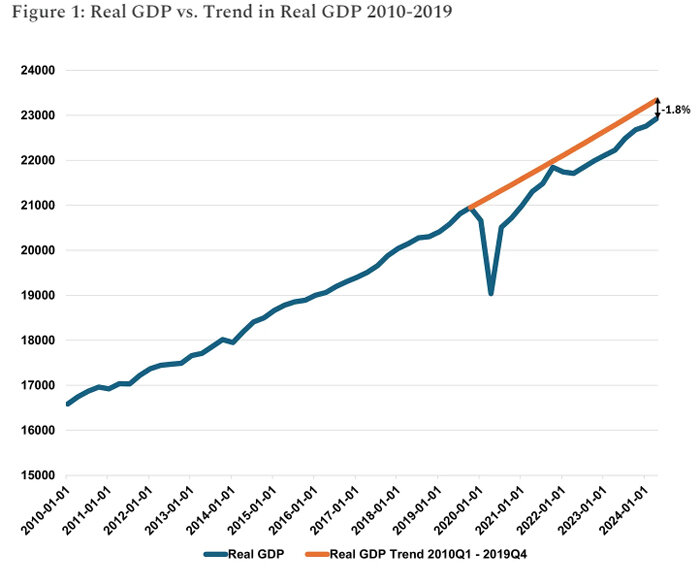

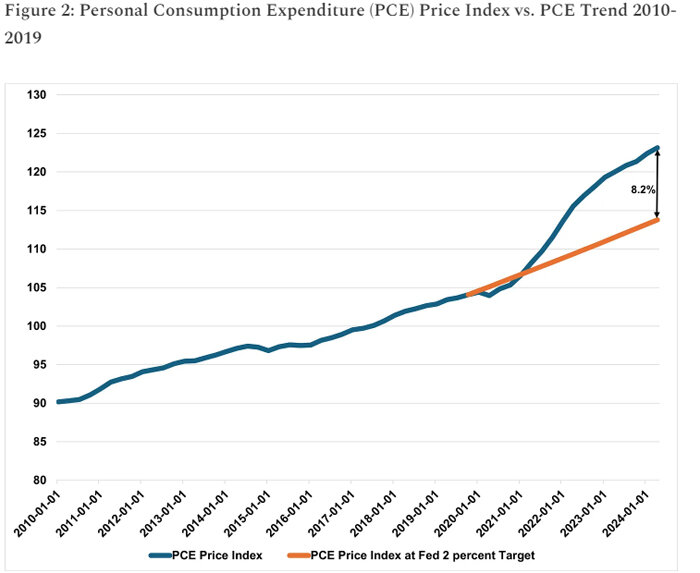

Is this story consistent with the trends in real output and prices we’ve seen since 2020? Not really. Real output growth across the whole U.S. economy hasn’t really been that weak compared with the trend of the previous decade — with the level of output currently standing about 1.8 percent below where we might have expected it to be if it had continued at its 2010–2019 trend (see Figure 1). In contrast, the price level the Fed targets, the Personal Consumption Expenditure index, is today 8.2 percent above the price level we’d have seen if inflation had been continually at target (see Figure 2).

In other words: Even if most or all this relative weakness in real output could be explained by a change in, or the exercise of, market power (something, remember, for which we have no to scant evidence), then this would still only account for a modest portion of the above-target inflation we’ve seen over the past four years.

Demand Matters Most In Explaining Inflation

So, what explains the recent inflation?

Stahl put to Khan that, rather than monopolies, “most economists say that it’s because of supply chains caused by Covid and the Ukraine war,” i.e. that these supply-shocks, by driving up firms’ costs, drove up the price level. And it’s true that, during 2022, say, the rise in oil prices did drive up the price level and so inflation. Yet, as Scott Sumner explained again last week, temporary negative supply-shocks can’t explain the permanently higher prices we’ve seen, which is what is driving public angst today.

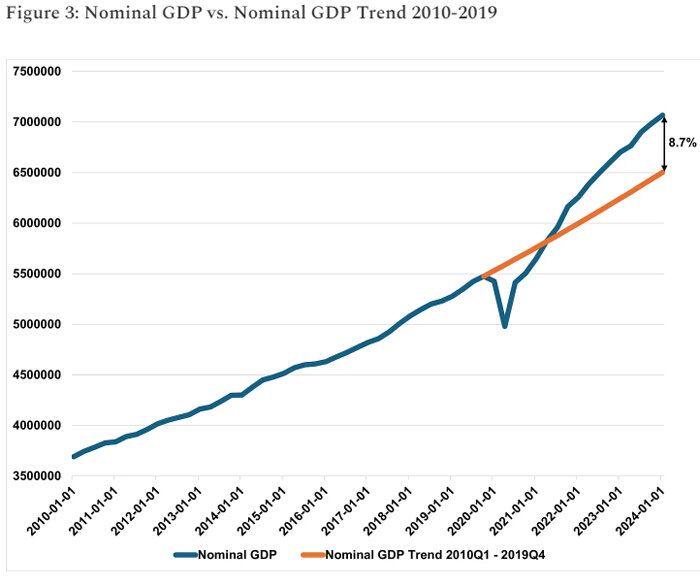

When supply-shocks unwind, they effectively deliver positive supply-shocks, and so periods of faster output growth relative to the growth in the money supply and velocity. That lowers price growth and so inflation again. Almost all of the COVID-19 supply shocks have now unwound and most of the Ukraine war supply-shocks too. Yet the price level is still 8.2 percent above where we’d be if inflation had remained at target throughout. This is not mainly a function of corporate concentration *or* supply-shocks, but the fact that the level of total spending on final goods and services (nominal GDP) has surged way above its pre-crisis trend and is now at a permanently higher level above trend (see Figure 3 below).

This is what the various “greedflation” theories always neglect to mention. Consumers were able to pay higher prices because macroeconomic policy was such that their money holdings had risen dramatically. Firms were charging higher prices precisely because the marginal willingness to pay for most goods had increased. In other words, many companies were charging higher prices because customers’ willingness and ability to spend meant the firms “could.” And that in itself is evidence of excessive macroeconomic stimulus.

Earnings Calls In Which Firms Celebrate Temporary Profits Are Irrelevant

When asked by Stahl directly whether she this believed “greedflation” to be true, Khan said “some executives boast on earnings calls about how inflation is great for their bottom line.”

This is a talking point we’ve explored before here: some greedflationists imply that because some firms enjoyed temporarily higher profits alongside increasing prices, this in itself is proof that profit-seeking, or greed, or whatever else you want to call it, *caused* inflation.

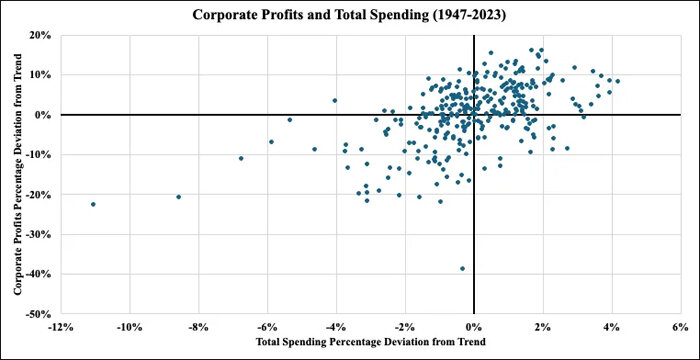

But, as my colleague George Selgin has noted, “Benefiting from inflation ain’t the same as causing it.” As I explained with Bryan Cutsinger, higher profits for many firms is exactly what we might expect if there was a large, unexpected increase in total spending across the economy, caused by a sharp growth in the money supply:

Such an environment can lead to higher short-term profits too because, in a range of sectors, retail prices tend to increase more quickly in response to rising spending than firms’ wages and input costs. The latter are often governed by contracts that are negotiated infrequently, meaning that when output prices rise, real (i.e., inflation-adjusted) wages and other input prices will fall. As a result, corporate profits can increase, at least until wages and input prices adjust.

People’s expectations about inflation play a crucial role in how wages and other input prices are set. In early 2021, few workers and input suppliers were expecting high inflation. They negotiated wage and other input price contracts on that basis. With spending rising and pushing up product prices, alongside stickier wages and input costs, many firms’ profits thus rose temporarily. In fact, as it became clear that the general price level was rising, some corporations no doubt raised their output prices in anticipation of their input and wage costs then going up, contributing further to a temporary profit spike.

The key point is that this wasn’t a function of greed, market power, or profit-puffing. The ultimate cause was a macroeconomic policy that had led spending to explode, forcing up all prices in the medium-term. And there is historical evidence for this short-term relationship between spending and profits too. One implication of this theory is that when total spending deviates positively from trend, corporate profits are likely to as well. Indeed, this positive correlation is precisely what we see in the post-war data for the U.S. (see Figure 2). Even relatively small deviations from trend in total spending are associated with large deviations in corporate profits.

In sum, “greedflationists” like Khan constantly confuse effect for cause in blaming profit-seeking for inflation. All that we’ve seen across the four years as a whole is consistent with monetary policy having been too loose, so driving the lion’s share of the above-normal increase in the price level.

People like the producers and CBS News and Khan constantly present us with a false dichotomy: that inflation was driven supply-shocks or corporate power. They point to facts to “prove” it. When input costs increase first and then retail prices, this is seen as “cost-driven” or “supply-chain” inflation. When retail prices rise first and costs second, it’s profit-led inflation or “greed.”

In reality, spending running wild can cause both of these outcomes, in the short-term, depending on where bottlenecks are first hit and which prices are most flexible. It’s just politically inconvenient to acknowledge that most of the blame lies with macroeconomic policymakers here in Washington DC.

If this were just blame deflection that would be one thing. But faulty theories lead to misguided policy. At best, FTC action against anticompetitive conduct might be able to reduce a good’s price in an individual market. Lina Khan, though, has no power over inflation, which is a macroeconomic phenomenon.