Vice reports that 32 economists have written to the federal government advocating rent control nationwide. Signatories include well-known figures like James Galbraith (University of Texas at Austin) and Isabela Weber (University of Massachusetts Amherst), the latter famous, of course, for popularizing the idea of “greedflation.”

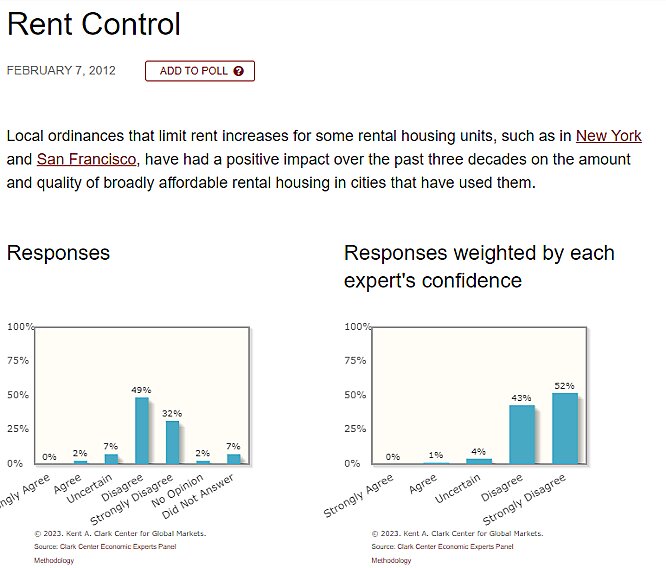

Now, this article caught my attention. Why? Well, generally, rent control doesn’t have a fan club among economists. Most surveys of academics find large majorities reject it as a desirable policy, mainly on the grounds that it tends to reduce the supply of rentable accommodation and lower its quality. When the Kent A. Clark Center for Global Markets polled 41 leading economists on rent control in 2012 (see below), just one person thought that rent control policies in San Francisco and New York had had positive effects on the amount and quality of affordable housing.

Yes, the economics of rent control depends, in large part, on the design of the specific rent regulation. Crude price controls applied to all rentable accommodation in a market, where rents can barely increase year-on-year, are likely to reduce the supply of rentable accommodation substantially. Less stringent regulation with lots of exemptions, especially for new construction, may not have as large an effect overall. But this letter implies that the economics of rent control itself is being fundamentally rethought, with economists more likely to reject the old Econ 101 supply and demand predictions. That strikes me as quite the claim.

So it’s worth examining the positive arguments these economists make for rent control’s revival.

CLAIM: Rent controls are like the minimum wage – economists are increasingly open to using them

“Among economists, the debate around the merits and drawbacks of rent regulation is in a similar situation as the minimum wage was in the late 20th Century….the past twenty years of empirical research analyzing the minimum wage have indeed found that minimum wage increases are effective at increasing living standards for low-wage workers with little to no impact on job loss…the economics 101 model that predicts rent regulations will have negative effects on the housing sector is [also] being proven wrong by empirical studies that better analyze real world dynamics.”

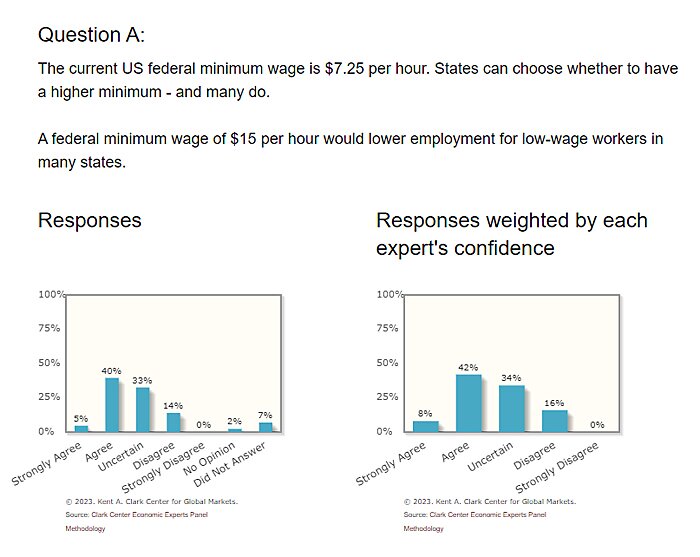

There’s definitely a heated debate among economists about the real-world impact of minimum wage laws. But this cited paragraph – suggesting that economists reject the traditional worries about trade-offs between wage floors and jobs — is a serious misrepresentation of the overall academic literature.

Take the work of David Neumark and Peter Shirley, who recently decided to dive into every study done on the impact of minimum wage increases on employment at the state and local level in the U.S. since 1992. What did they find? About 79.3 percent of studies showed a negative effect of minimum wage hikes on employment, especially for groups like teens, young adults, and less-educated workers.

Sure, there are some headline-grabbing papers out there suggesting that minimum wages don’t kill jobs, but even those findings (which often examine one industry) don’t hold up too well under changes in methodology. That’s why, in general, economists still think the level of the minimum wage matters, that raising it very aggressively is risky, and that a federal minimum wage hike will hit some low-productivity, low-wage areas hard.

In fact, a Kent A. Clark Center for Global Markets poll from February 2021 revealed that, weighted by their certainty, half of the economists polled agreed that a sharp increase in the federal minimum wage would lead to a drop in employment for low-skilled workers in many states. Only 16 percent disagreed.

I’ve seen far less published evidence still to suggest that there’s some great revision underway about the economic effects of governments capping rents.

CLAIM: Rent control lowers rents in regulated markets

“For example, empirical research on local rent control policies in San Francisco, CA and New York, NY found that rent regulations lower housing costs for households living in regulated units.”

Their first economic claim of substance is to state that rent controls tend to lower rents in regulated markets. Well, yes? If the point is to set binding ceilings on what tenants must pay, lowering the costs of renting, then provided those controls are effectively policed, people still renting the affected properties will indeed pay less than they would have done in a free-market. Nobody disputes this.

The real questions are a) do the actual real-world controls that politicians implement bind and thus keep rents below the market rate? b) when they do, does this lead to a reduction in the supply of rentable accommodation, a deterioration in the quality of rentable accommodation, or create other economic dysfunctions?

It’s true that some of the softer forms of rent control, like in New Jersey, do not seem to lower rents much below market rates, if at all. This is not that surprising, given that the laws there in many localities guarantee substantial annual rent increases, exempt new construction from the rent regulation, and allow landlords to use “hardship appeals.” That makes them less likely to bind, and thus less effective in making renting more affordable.

If the controls do hold rents below market rates, that’s when we’d expect the supply of rent-controlled homes to fall in favor of other forms of tenure. Rent-controlled properties will be cheaper than market prices, but these controls can cause overall market prices to rise.

Why? If there’s a meaningful exempted rental sector, then rent prices for these accommodations can sometimes be pushed higher as demand that hasn’t been satisfied by rent-controlled properties spills over into the non-controlled sector.

For example, one study has found that San Francisco’s 1994 rent control law caused a 5.1 percent citywide rent increase from 1995 to 2012. Perhaps counter-intuitively, by shifting more demand into the uncontrolled sector, rent controls can sometimes drive-up underlying market rents overall, then, even if they reduce rents among the controlled properties.

CLAIM: Rent controls reduce cases of economic eviction, and this is good news

“Evidence from San Francisco shows that rent control helps stem tenant displacement in a high-cost market. International research on national rent control policies like that of Denmark similarly show that rent regulation is associated with a reduction in tenant mobility… rent regulations can benefit the economy as a whole, helping people stay housed closer to their jobs and communities, and making it easier for employers to find qualified job seekers locally.”

The next claimed benefit is that rent control essentially stops tenants being displaced by sharp rent rises. Signatories chalk this up as unambiguously good news, presumably because they think it reflects tenants being less likely to have to leave a property because of rent increases when they don’t want to (a so-called economic eviction).

Yet one reason for less mobility among tenants in rent-controlled properties is that artificially low rents mean tenants want to stay in apartments due to their lower costs, even when those apartments are no longer unreflective of their needs or other people might value them more highly. That makes it more likely the accommodation itself will be too big, too small, has or lacks other features, or is in the wrong location, and so does not reflect a tenant’s true willingness-to-pay.

A 2003 paper on New York City found 21 percent of tenants in rent-controlled units had more or fewer rooms than similar tenants in a free-market. This sort of misallocation is economically destructive. The letter assumes rent control helps people stay closer to jobs, but this misallocation can create a barrier to workers living near to their best job matches or even new, more lucrative long-term opportunities.

CLAIM: Rent controls don’t limit housing supply

“There is substantial empirical evidence that rent regulation policies do not limit new construction, nor the overall supply of housing…there are studies that show that rent control laws can cause landlords to search for loopholes, such as condo conversions, that impact the supply of rental housing; however this simply highlights the need for policy design to eliminate loopholes.”

Rent control is said to have little downside, per the letter, because it doesn’t dampen new housing construction nor the overall housing supply.

Did you notice the careful wording of the latter part? No economist thinks rent control meaningfully reduces the overall supply of housing of all tenures — people need places to live, after all. So that claim attacks a straw man.

The more controversial assertion here is that rent control does not reduce new rentable housing construction. Yet my read of the evidence is that rent control only has benign effects here if the regulations specifically exempt new builds – i.e. if new builds are not rent-controlled.

Under cruder, more pervasive rent controls, new building of rental accommodation can collapse quickly. In 2021, St. Paul, Minnesota approved a stringent rent stabilization ballot measure that capped rent increases at three percent per year, regardless of inflation. Immediately, new multi-family building permits plummeted 80 percent, while increasing almost 70 percent in neighboring Minneapolis.

The city council thus rowed back on the ordinance to exempt newly-built units from controls, creating a class of rentable accommodation not subject to the regulations. Most modern rent control laws have this exemption, so it’s little surprise that many modern rent controls have less of an impact on new building today. In fact, it’s even possible that the displacement of the excess demand caused by rent regulations in the regulated market leads to more new-build construction overall (if those who can’t find accommodation are those with the highest willingness to pay).

However, the important thing to recognize is that, to the extent new construction does occur, it’s because of the absence of rent control applied to those units, not a feature of it. Rent control itself still undermines the supply of the rentable accommodation it affects. Any additional new construction merely reflects the distortions that the price control creates in one part of the sector.

Aside from the issue of new construction, what we know for certain is that rent controls incentivize people to convert their existing rental apartments to non-controlled forms of tenure. This reduces the pool of regulated rentable accommodation available. In 1994, San Francisco expanded rent control to small multi-family housing. One study shows that the supply of rental accommodation from affected landlords fell by 15 percent, as many landlords sold them as owner-occupied condos. A 2007 study of the Boston metropolitan area found the flip-side: ending rent controls increased the supply of rental housing, despite having little effect on new construction.

In Stockholm, Sweden, where strict controls have been enforced for decades, the average wait time to obtain a rent-controlled apartment in some places can now exceed 20 years. When Berlin froze rents at 2019 levels in 2020, the law led to a swift and large reduction in advertised rental units.

Changing a property to an exempted tenure type (whether a new build, a condo, a holiday home, or another repurposing) should not be thought of as landlords exploiting “loopholes” in rent control laws. It simply reflects that reducing the profit opportunities from renting out results in fewer rental units. The more stringent you make the rent control laws to avoid such effects, the more likely would-be landlords will adjust on other margins, like allowing the quality of accommodation to decline (as was seen in Boston).

CLAIM: Rent controls are good for the poor

“Rent regulations can also be a powerful tool to reduce inequality and promote economic diversity. In addition, unlike most assistance programs, rent regulations do not require significant public resources to administer. Absent rent regulations, we see rising homeless rates leading to increased public expenditures on emergency rooms, jails, prisons, and the courts system.”

The final argument made for rent controls is that they benefit low-income and minority households who would otherwise face sharply rising rents. This supposedly redistributes from wealthy landlords to poor tenants, preventing gentrification and protecting the most disadvantaged from a range of economic harms.

The extent to which rent controls are “progressive” really depends on the coverage of any rent control scheme. Few are designed such that only poor people are eligible for rent-controlled properties. As a result, there is simply no guarantee that the people who benefit from below-market rents will be poor.

In Boston, for example, one study found only 26 percent of properties were occupied by the poorest quarter of households, while 30 percent of controlled units were occupied by the richest half. An older analysis of New York and a more recent study of St Paul likewise found that the benefits of rent control were higher for rich and white tenants than for their poorer and minority counterparts.

The simple fact is that if you don’t allocate properties by price, you need some other mechanism. That might entail more extensive search by tenants, screening from landlords, higher deposits, or a willingness to live in a crumbier property in disrepair. None of these are guaranteed to be pro-poor. With rent controls imposing more risk on landlords, they may face greater incentives to search for tenants who will make their properties more attractive in other ways, which might lead to a pro-rich bias, implemented through cronyism, discrimination, or even side-payments.

To the extent that rent controls either reduce the new building of rentable accommodation or lead to conversions into condos or other exempted forms of tenure, the poor get hurt disproportionately. They are less likely to be able to afford down payments to buy a house, after all, so are then left languishing in a smaller rental market, making it more difficult for them to find properties.

This is why, in some cases, rent controls can actually accelerate gentrification, rather than quell it. In San Francisco, landlords responded to rent controls by converting rental units into upscale condos, attracting residents with incomes at least 18 percent higher. There’s therefore no a priori reason to expect rent control in general to be progressive.

Looking at the sum of the arguments, it’s hard not to conclude that this letter fundamentally misrepresents the economic theory and evidence base on rent control. It seems to be a case of policy-driven evidence selection.

So why does this matter?

Well, because these arguments are being deployed in the service of attempting to change federal policy. The basic demand is that the Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA) should implement a regulation that any landlord that has obtained borrowing from a government-backed enterprise can only raise rents by a maximum amount, say, of 3 percent per year. Given FHFA institutions back the financing of about half of multi-family rent controlled units, this would apply a crude price control to a large proportion of the U.S. housing stock.

Such a control, divorced from the supply and demand conditions of housing, would cause significant shortages in “hot” markets. It would lead a lot of landlords to shift their properties into other forms of tenure, hurting some poorer tenants who can’t afford down payments for owner occupation. Given there is no stated exemption for new build accommodations, we’d expect to see investment in new rentable multifamily housing decline sharply too, despite the signatories’ assurances to the contrary.

The federal government should reject this idea outright.