Venezuela is in the throes of an unprecedented economic collapse. Oil, Venezuela’s lifeblood, is being mismanaged by Petróleos de Venezuela (PDVSA), the country’s state-owned oil company. Faced with dwindling revenue from PDVSA, the government has relied on its central bank to finance public expenditures. To satisfy these demands, the Banco Central de Venezuela has turned on the printing presses, and, as night follows day, hyperinflation has reared its ugly head again.

In total, there have only been 62 episodes of hyperinflation in history. Venezuela, along with Lebanon, is one of only two countries currently experiencing hyperinflation. Today, Venezuela’s annual inflation rate is 2,275 percent per year, the highest in the world.

How could this be? After all, Venezuela has the largest proven crude-oil reserves in the world. At 303.81 billion barrels, they are larger even than Saudi Arabia’s, which stand at 258.6 billion barrels. Considering the extent of the country’s resources, it might strike most people as surprising that Venezuela’s hyperinflation is linked to the mismanagement of PDVSA, a state-owned enterprise (SOE). But PDVSA dominates the Venezuelan economy and accounts for 99 percent of Venezuela’s foreign-exchange earnings. In a sense, PDVSA is the Venezuelan economy, and even by SOE standards, the company is grossly mismanaged.

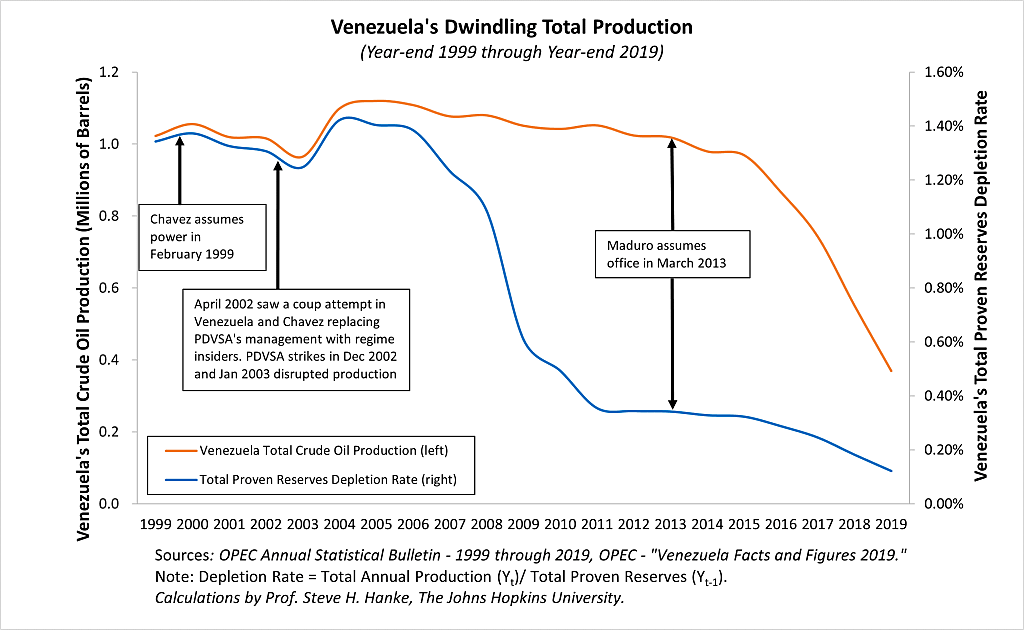

Under the direction of Luis Giusti in the 1994–98 period, PDVSA’s production soared. This trend changed in 1999, when Hugo Chavez became Venezuela’s president and introduced Chavismo as the country’s guiding economic doctrine. Venezuela’s oil output began to stagnate, a situation that worsened further after the coup attempt of April 2002. Chavez responded with mass purges of PDVSA’s employees, replacing them with “reliable” hands — those loyal to Chavez’s socialist regime.

After the 2002-03 output plunge, Venezuela’s oil production temporarily recovered. However, with the death of Chavez and Nicolas Maduro’s assumption of the presidency in March 2013, another output plunge began. This trend has left Venezuela’s output drastically lower than when Chavez took power in 1999 (see the chart below).

In addition to the reduction in PDVSA’s crude oil output, its physical capital has been consumed at an unsustainably rapid rate, with capital expenditures far below the value of equipment that is being consumed each year by depreciation and amortization.

There has also been a drop in the stock and quality of PDVSA’s human capital. In 2017, President Nicolas Maduro named a National Guard general, Manuel Quevedo, the leader of PDVSA, despite his having no industry experience. Quevedo was soon ousted by Asdrubal Chavez, a cousin of Hugo Chavez, in late April 2020 despite the new leader’s international reputation as a drug lord.

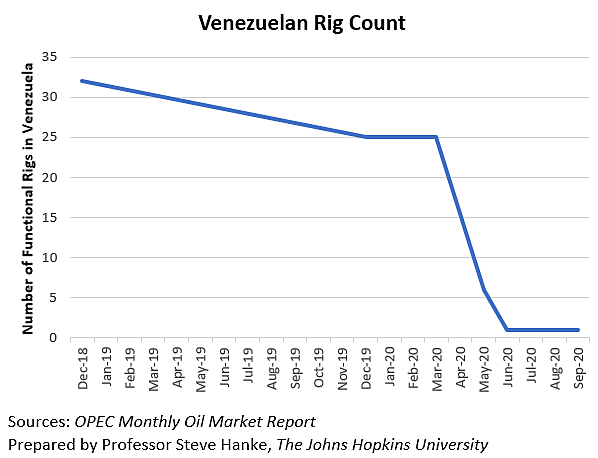

Unsurprisingly, PDVSA’s chronic mismanagement has been accompanied by a recent collapse in the number of operational oil-drilling rigs in the field (see the chart below). Indeed, it has been reported that, as of August 2020, PDVSA has no operational oil rigs.

If all that isn’t bad enough, equipment breakdowns and increased accident rates have contributed further to long downtimes and output declines. As of October 1, 2020, PDVSA had reported 42 accidents and incidents since 2003, costing the SOE approximately 580 days of production. Because many of PDVSA’s blunders go unreported, and many of the mismanagement incidents (such as the sinking of the natural gas exploration rig “Aban Pearl”) cannot be quantified in terms of days lost, the true number of days in which PDVSA’s production has been hampered due to mismanagement is undoubtedly much higher than reported figures.

PDVSA’s decreased output is not due to dwindling oil reserves, but instead due to a reduction in its depletion rate. The depletion rate — the rate at which oil companies are depleting their proven reserves — provides the key to understanding the economics of an oil company and the value of its reserves.

Venezuela’s depletion rate has been falling rapidly since 2007 (see the first chart). In 2019, it sat at 0.121 percent per year, indicating that it would take 569.41 years for PDVSA to tap half of its reserves.

This has noteworthy economic implications. Because of positive time preference and discounting, the value of a barrel of oil produced today is higher than the value of a barrel of oil produced in the future, provided the price of oil remains the same. Given Venezuela’s incredibly low depletion rate, its reserves are essentially worthless because they are left in the ground for too long.

To put Venezuela’s depletion rate into perspective, consider Exxon, one of the world’s largest oil companies. At the end of 2019, Exxon’s depletion rate was 6.53 percent per year —comparable to that realized by most major oil companies. That rate implies that it would take 10.25 years for Exxon’s oil reserves to be halfway depleted. That is 559.16 years earlier than when PDVSA would deplete half of its reserves. If we discount at 10 percent, the median value of Exxon’s reserves is worth 37.65 percent of their wellhead value (the value that the producer would receive if the oil was sold at the wellhead and not distributed further downstream) — not zero, as is the case for PDVSA.

Thanks to Venezuela’s embrace of socialism and Chavismo, PDVSA has probably destroyed more economic value than any institution in world history. This brings back memories of President George W. Bush’s infamous remark that “this sucker could go down.” It’s no surprise that the clergy are preparing to administer PDVSA’s last rites.