Dear Capitolisters,

Recent events have me thinking, as one does, about U.S. sugar policy. First and most obviously, it’s the Christmas season, and my sugar intake—along with my waistline—has predictably increased. (I blame Santa.) Second, controversy erupted last week when U.S. food manufacturer (and major industrial consumer of sugar) Kellogg’s announced that—after its unionized workforce rejected the company’s latest labor contract offer—it would hire non-union workers in the meantime. This prompted a rather, ahem, unique statement from President Biden, saying he was “deeply troubled” by the move. Since both events implicate U.S. sugar policy, which significantly burdens not only American families, but also U.S. companies like Kellogg’s and their workers, there’s no better time to dig into the issue.

So go grab a(nother) frosted cookie, and let’s get down to it.

How the U.S. Sugar Program Works

As helpfully summarized in a 2018 paper by my Cato colleague Colin Grabow, U.S. government support for sugar—some form of which has been in place since 1789!—has four main pillars today:

-

Price support loans. The USDA offers government loans secured by domestic producers’ sugar as collateral, which borrowers can either repay with interest or default on if prices go below a fixed price. Because producers will simply forfeit their sugar collateral if the market price dips below this price, USDA must restrict domestic sugar supply to boost prices. Those supply restrictions are implemented through the second and third pillars, discussed next.

-

Marketing allotments. USDA annually determines an overall limit on how much sugar can be sold in the United States to avoid loan defaults and reserve 85 percent of the U.S. sugar market to domestic producers, as required by law. This quantity is divided among sugar cane and sugar beets, as well as among various states.

-

Sugar for ethanol (no, really). USDA also can buy domestic sugar to keep it off the consumer market (and thus keep prices high). The agency then sells this sugar to U.S. ethanol (of course) producers, often at a big loss (of course).

-

Import quotas. Finally, the United States imposes strict quotas, divided among 40 different sugar-producing countries, capping the amount of sugar that can be imported into the country duty-free. Any imports above those (very low) quantities are subject to a high tariff (approaching 100 percent) that effectively bars these goods from the market.

The only exception to this complex system of price, supply, and demand regulations—which you couldn’t make more economically ridiculous if you tried—was Mexico under NAFTA. However, the United States closed that “loophole” in 2015 with a good ol’ “trade remedy” investigation and subsequent U.S.-Mexico “suspension agreement” that restricts Mexican sugar imports and keeps U.S. prices high.

The Program’s High Economic Costs

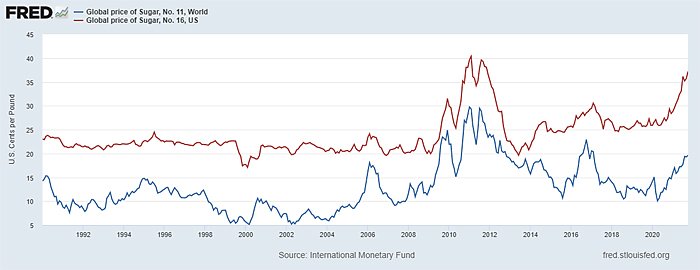

As you can probably guess, this Rube-Goldbergian system has imposed all sorts of harms—intended and unintended—for the United States and abroad. Most obviously, tight government restrictions on domestic sugar supplies have ensured that U.S. consumers pay far more—sometimes three times as much—for sugar than the rest of the world does:

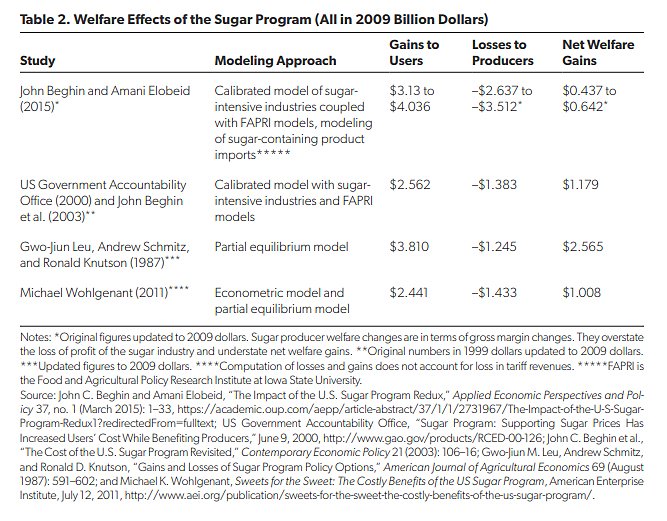

This price differential, which is today about two-fold, adds up. For example, Bryan Riley of the National Taxpayer Union Foundation did a back of the napkin calculation a few months ago and found that American consumers paid as much as $6.2 billion more for sugar during 2020–21 because we were forced to pay the U.S. price instead of the world market price. More sophisticated analyses have found much the same: As shown in the table below (from this 2017 AEI paper), for example, eliminating the sugar program would lower sugar prices and thus generate as much as $5.3 billion in annual benefits (in today’s dollars) for users:

Since sugar is a primary ingredient in all sorts of foods, these costs don’t just hurt you and me, they also harm domestic food manufacturers—such as candymakers, bakers, and (ahem) cereal producers—and their workers. The aforementioned AEI report, for example, concluded that the sugar program results in the annual loss of about 20,000 jobs in U.S. food processing industries, and Grabow details how many companies, including Kraft Foods, have just abandoned the country altogether instead of enduring a massive tax on one of their main ingredients. As one quoted executive explained, “It’s really not that much of a choice. … You move or you go out of business.”

Heckuva incentive system, huh?

According to Canada’s Globe and Mail, American sugar protectionism has been a particular boon for our northern neighbor, with Ferrero, Nestlé SA, Tootsie Roll Industries Inc., Mondelez International Inc., and Mars Inc. all setting up shop there to serve the U.S. market. According to one industry rep, “There’s no question that our ability to sell world-price sugar in a confectionery product in the U.S. has helped our ability to sell products down into the U.S.” (Hey, good for them… I guess.)

Grabow then explains that these harms aren’t just anecdotes:

A Wall Street Journal analysis of U.S. Census Bureau data found that total U.S. confectionary manufacturing employment declined by 22 percent from 1998 through 2011, while a 2006 Commerce Department study concluded that “for each sugar growing and harvesting job saved through high U.S. sugar prices, nearly three confectionery manufacturing jobs are lost”; every sugar job saved was at a cost of $826,000. A 33 percent rise in the amount of sugar contained in imported products from 2002 to 2012 is also suggestive of an overseas production shift by sugar-using companies.

You and I—and small businesses—don’t have much choice when it comes to paying the U.S. sugar tax, but large, multinational manufacturers sure do. And instead of ponying up, they’re voting with their feet—to American workers’ detriment.

So Many Other Costs

The sugar program’s economic costs, however, are just the tip of the iceberg. Other harms include—

-

Health costs from increased American consumption of good ol’ high fructose corn syrup, which many manufacturers choosing to stay in the United States, such as Coca-Cola, use instead of sugar because it’s cheaper here. (Coke also imports the Mexican version, which contains real cane sugar and tastes better.) The U.S. sugar industry also has a long history of using its subsidized wealth to downplay possible health risks—obesity, heart disease, etc.—associated with increased sugar consumption.

-

Foreign policy costs. Economic development in poorer neighboring countries—which have climates and workforces more suited for cane sugar production yet are effectively shut out of the massive U.S. market—has been stunted, thus increasing domestic instability and international migration (including through our porous southern border) and often confounding the United States’ own foreign policy objectives. One particularly egregious example: 1980s “sugar quotas … led farmers in the [Caribbean and Central American regions] to stop producing sugar and start cultivating illegal narcotics that were smuggled into the United States, starting a war with drug traffickers.” Such harms further undermine the already-ridiculous assertion of a certain Florida senator that U.S. sugar protectionism is a pillar of our “national security.” (No, he really said that!)

-

Environmental costs. As R Street’s Clark Packard explains, sugar production in the United States has been particularly bad for Florida: “A substantial majority of phosphorus that ends up in the Everglades comes from sugar cane farms. Canals that divert phosphorous away from the Everglades instead end up contributing to massive toxic algae blooms that kill wildlife and force public beaches to close.” Earlier this year, moreover, ProPublica found that fires set by Florida cane harvesters to clear their fields exposed nearby residents to dangerous levels of particulate matter (air pollution), leaving many of them struggling to breathe. A lawsuit is now ongoing.

-

Other trade costs.U.S. government intransigence on sugar policy means that our trade negotiators are frequently forced to settle for worse terms on non-sugar issues in U.S. trade deals. For example, in exchange for keeping sugar liberalization out of the U.S.-Australia free trade agreement, the United States softened its demands that Australia liberalize protected sectors like pharmaceuticals, wheat, and media services—sectors in which the United States actually has a strong comparative advantage (unlike in sugar)! Sugar also confounded past WTO/GATT talks and Trans-Pacific Partnership negotiations.

And Then There Are the Political Costs

The sugar program persists in spite of these costs for the same “public choice” reasons that the Jones Act and all sorts of other failed programs continue long after their failures have been established. For starters, sugar interests are located in electorally important areas like Florida (cane) and the Midwest (beets), and they’ve teamed up with politically powerful corn farmers (who enjoy increased consumption of HFCS) to oppose even the most modest of reforms. The sugar program is also a classic case of diffuse costs and concentrated benefits: Each of us pays maybe $20 per year for higher sugar prices (unless we’re, like, really into baking or something), while each U.S. sugar farm—according to AEI’s Vince Smith—gets an annual windfall of $290,000. The biggest players, such as Florida’s infamous Fanjul brothers, make much, much more. So it’s not worth it for each of us to spend time and money working on sugar reform, but it surely is for Big Sugar.

And boy do they work—engaging in some of the most aggressive and effective lobbying and P.R. in the country (just ask literally anyone who’s ever worked on Capitol Hill).

NTU’s Riley provides the telling numbers: “Even though sugar represents 1.36 percent of the value of all crop production, it represents roughly a 55 percent share of crop production lobbying and 9.66 percent of agribusiness lobbying money.” Smith adds that U.S. sugar producers and processors in 2020 donated more than $6 million in campaign cash to congressional members, Republicans and Democrats, from 48 different states (most of which aren’t home to beet or cane production but are home to members of the House and Senate agriculture committees).

These bipartisan dollars translate into wins: A new working paper, for example, found that a substantial (50 percent) increase in “Big Sugar” contributions to House incumbents between 2013 and 2018 “significantly raised the probability that the targeted representative would vote against reforming the sugar subsidies” and thus ensured that modest 2018 reforms were voted down by large margins. ProPublica adds that this political mobilization also occurs at the state level (emphasis mine):

In Tallahassee, the sugar industry operates one of the most formidable lobbying forces in Florida. U.S. Sugar and Florida Crystals have individually outspent every other company in the state on lobbying at the administrative and legislative levels since 2018, when the state first started its digital lobbyist pay database, a Post and ProPublica analysis found. That includes outspending corporate giants like Walt Disney Co., Florida Power & Light, and HCA Healthcare. At times, the two sugar companies combined employed more lobbyists than there are state senators.

Incredible.

Finally, Don Boudreaux of George Mason University reminds us that these activities have not only obvious political costs, but alsomore hidden economic ones:

But there’s one additional cost of this program that warrants mention—namely, the vast amount of resources used by sugar and corn producers to lobby for this program. All the time and talent of those persons employed to plead for this special privilege are time and talent that could be, but aren’t, instead used productively—to produce goods and services that would enhance our living standard. This time and talent are spent convincing politicians to plunder all Americans in order to unjustly enrich a few. The output forgone because so many scarce resources are spent, not producing, but pleading for special privileges is a huge cost on top of the higher food prices that we must pay.

All of these costs surely swamp any benefits that the sugar program might confer on domestic producers and workers. But it’s not even clear that reform would kill off the domestic industry. Research shows, for example, that both Canada and Australia (one of the largest sugar exporters in the world) have healthy industries and lack significant government subsidies or import protection. AEI’s Smith adds that the pain of eliminating the sugar program would be particularly muted for Midwestern beet farmers, who can only use each field once every four or five years because of the impact on the soil.

But, yeah, good luck convincing Congress of that. (Maybe try at the next Fanjul party. Sigh.)

Summing It All Up

I snarked on Twitter that maybe Kellogg’s could afford to pay its employees more if it weren’t paying twice as much for sugar as do food-makers abroad. That was an obvious troll (and successful play for social media attention!)—labor contracts depend on all sorts of things—but there is a nugget of truth in there. In particular, some of Kellogg’s most popular food items are heavy on sugar, and the company lists the commodity as one of a handful of “principal raw materials” used in its products. It annually spends about $9 billion on production costs, including raw materials and labor, and a 2002 Census survey of all U.S. breakfast cereal manufacturers shows that they spent about half as much on sugar (around $254 million) as they did on wages (about $549 million). Cut their sugar bill in half (or more), and there’d be more revenue available for workers.

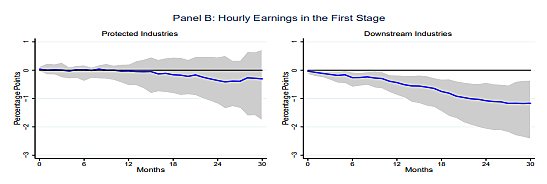

Would Kellogg’s actually do that? Who knows! But various economic studies show that downstream manufacturers facing lower imported input costs do tend to raise wages, and that those facing higher input costs—for example due to trade remedies actions—do the opposite:

Combine these general data with the fact that Kellogg’s profit margins have been steady over the last few years (and well below those of their competitors), that U.S. sugar restrictions have been repeatedly found to cost American jobs, and that Kellogg’s started importing cereal from its factories abroad to offset labor troubles in the United States, and it’s not crazy to think that at least some of the benefits of lower sugar prices would be passed on to Kellogg’s employees (instead of, say, just banked as higher profits).

Regardless, it’s all just another reminder that protectionism—especially when applied to key industrial inputs—isn’t “pro-worker” at all; it’s pro-some-workers—at the expense of many others, all American consumers, and the economy more broadly.

It’s enough to put you in a sour mood.

P.S. You can’t make this up.

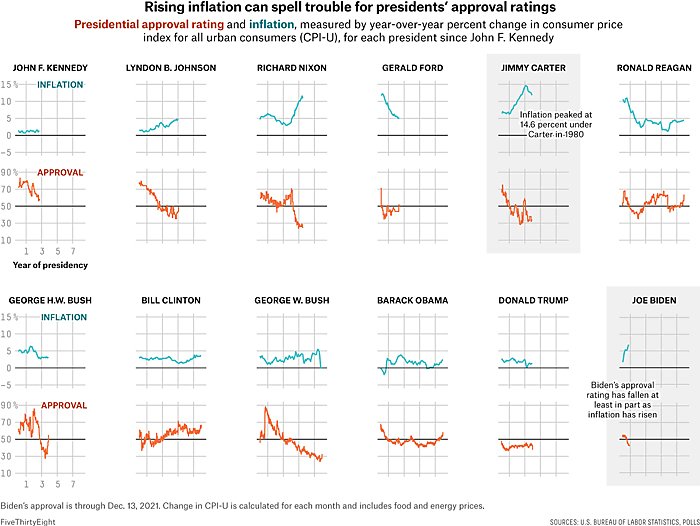

Chart of the Week

(Link.)

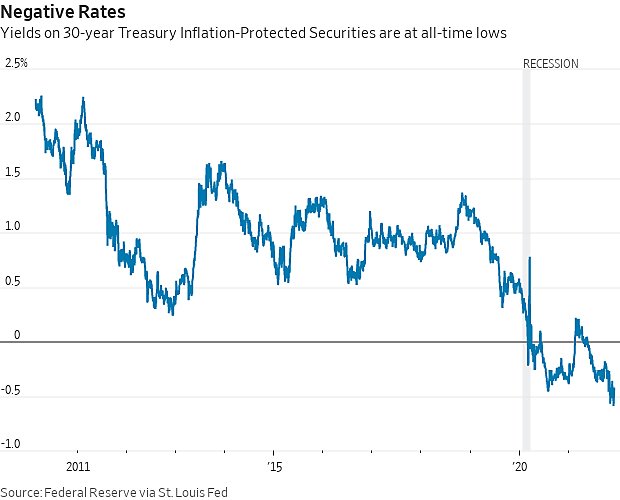

Bonus Chart of the Week

Good Wall Street Journal primer on Fed policy and “real” interest rates

The Links

Inflation hitting wages (more)

“Longstanding Anti‐Price Gouging Statutes Worsen Shortages”

“The Nasty Realities of Steel Protectionism”

American ports can’t handle increasingly large container ships (more)

That Mancur Olson, so hot right now

Good move by Biden on hearing aids

Canada’s pretty mad about proposed U.S. EV subsidies

Cars are crazy expensive right now

Open borders, vaccinated Dubai is booming

Paper: U.S. immigration restrictions stymie entrepreneurship