President Biden is pushing Congress to pass a federal rent control law. His proposal would require corporate landlords to limit rent increases on existing units to 5 percent per year or lose specific federal tax benefits, such as depreciation write-offs. This essentially means a nationwide 5 percent cap on annual rent hikes for affected units.

Biden’s team has made clear this would apply only to corporate landlords with over 50 units—about 20 million units nationwide—and would last for two years. New rental housing and properties undergoing major renovations would be exempt. The administration believes these carveouts will avoid reducing the supply of rental housing while the price ceiling itself will prevent large rent increases for tenants until new housing is developed.

The former is wishful thinking. Rent prices reflect the changing scarcity of rental housing in a market. A federal rent cap that binds will reduce the profitability of renting out existing properties in high-demand, hot areas. Empirical evidence shows that such price controls, on the margin, will encourage landlords to convert rental units into condos, cut back on maintenance, and become more selective about tenants to reduce rent default and vacancy risks.

As a result, both the quantity and quality of rental housing would decline. This especially hurts poorer renters who can’t afford down payments and often live in lower-quality housing to begin with. The time costs of finding housing will rise due to greater scarcity. And there are macroeconomic consequences too. Tenants benefiting from below-market rents will likely stay longer in housing that may no longer suit their needs, reducing geographic and job mobility, which can negatively impact the broader economy.

Biden’s team claims that exempting new builds from these controls will avoid deterring new rental housing supply. However, this isn’t necessarily true. Introducing federal rent control sets a precedent, signaling that the government is willing to cap rental prices to improve affordability. The expectation of broader controls in the future could scare off rental housing investments today, ultimately worsening the housing crunch and raising market rents.

If I wanted to make the most optimistic case that this policy is no big deal, I would argue that by pre-announcing the intention for such short-term controls, landlords in markets where rents are expected to rise quickly may just “front-load” their rent increases now. As such, the price control might not bind for as many properties over the two years.

Moreover, even landlords who don’t front-load rents can still adjust in other ways under Biden’s proposal. If market rents are set to rise by 7 percent but are capped at 5 percent, landlords could reduce services or introduce new fees—such as closing the pool, not replacing gym equipment, or charging for groundskeeping and trash. This means the quality-adjusted rent would effectively increase more than the headline rent figure suggests, reflecting the true market conditions.

However, this rose-tinted perspective ignores the politics of rent controls. These kinds of adjustments usually anger tenants and often lead to additional regulations on landlords. If federal rent control is introduced, the creation of a beneficiary class means it’s likely to extend beyond two years and come with more rules, amplifying the historic downsides of rent control detailed in Chapter 8 of The War on Prices.

It’s important to note that opposition to rent control isn’t just a libertarian viewpoint. Economists of all political persuasions overwhelmingly reject governments controlling rent prices. Jason Furman, chair of President Obama’s Council of Economic Advisers, told the Washington Post this week:

Rent control has been about as disgraced as any economic policy in the tool kit. The idea we’d be reviving and expanding it will ultimately make our housing supply problems worse, not better.

That’s the case even if future units are exempted, Furman said, because it could change how developers consider their incentives.

Of course, there are always some economists who will support any policy proposal. For instance, Justin Wolfers has argued that Biden’s proposal isn’t too draconian and that holding down rent increases might even lower measured inflation, helping out the Federal Reserve.

One of the key takeaways from The War on Prices, however, is that you can’t cure a macroeconomic inflation—caused by an imbalance between total spending and output growth—by controlling individual product prices. Suppressing one product’s price simply redirects inflationary pressures, with the excess money pushing up demand and so resulting in higher prices elsewhere in the economy. To a first approximation, this policy wouldn’t affect medium-term inflation at all.

That means we should focus on the economic inefficiencies it would create. We’d all be better off if this idea was quietly junked.

For more on rent control and the myth that individual product prices “drive” inflation, do read The War on Prices book.

Make Monetary Aggregates A Consideration Again!

Speaking of the causes of inflation, monetarists were ahead of the curve in warning about the post-pandemic take-off in prices, because they paid attention to data that showed a ballooning money supply. So it was interesting to see Harvard economist Greg Mankiw recently argue that central banks should pay more attention to monetary aggregates again (particularly, I might add, when they really surge!)

After the difficult 1980s experience of money supply targeting to control inflation, it has become trendy among economists to dismiss the essential insights of the quantity theory of money entirely. But Mankiw challenges this dismissal, arguing that the criticisms of focusing on the money supply are equally, if not more, applicable to the modern “output gap” analysis favored by modern macroeconomists:

Most arguments that people make to justify ignoring these [monetary] aggregates don’t hold much water.

Some people point out that measuring the quantity of money is hard in a complex financial system such as ours. That is true, but as I have discussed, it is also hard to gauge how much slack there is, and that hasn’t stopped people from trying to measure it to judge inflationary pressures.

Other people point out that monetary aggregates have a poor track record in forecasting inflation in recent years (at least before the pandemic surge). That’s true as well. But the Phillips curve also has a poor track record as forecasting tool (Atkeson and Ohanian 2001), and that doesn’t stop people from focusing on it.

Still other people note that central bankers these days don’t talk much about monetary aggregates in their policy announcements. That’s also true, but perhaps they should. In any event, monetary economists should not take their lead from central bankers any more than economists studying optimal taxation should feel constrained by the rhetoric of the House Ways and Means Committee.

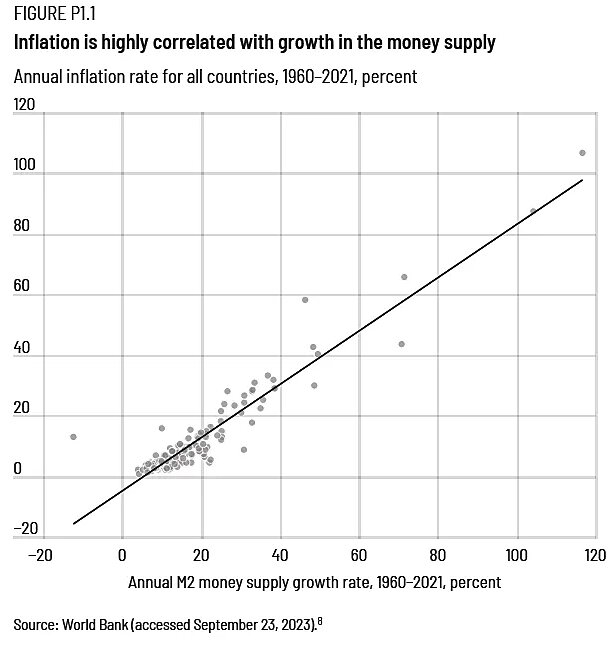

Too true. I would add that there is good evidence that the quantity theory of money holds across countries in the long-run, with a fairly tight relationship between growth in the money supply and inflation (see below). The same certainly can’t be said for the short-term output gap or slack framework that policymakers often discuss.

Yes, in the short term, the relationship between the money supply and inflation can be muddied, such that small money supply movements aren’t great for predicting inflation. This complexity is partly due to the nature of inflation targeting. As I explain in The War on Prices:

Mankiw’s essay is worth reading in full. Like David Beckworth in The War on Prices, Mankiw argues that policymakers struggled with this inflation because it was hard to distinguish between “demand shocks” and “supply shocks” affecting the price level in real-time. This uncertainty made it difficult to determine how much of the inflationary pressure was truly “transitory” and due to supply-chain issues, so delaying the Fed’s necessary decision to tighten policy.

Beckworth’s analysis revealed that the bulk of the permanent increase in the price level post-pandemic is due to excessive spending in the economy, indicating that macroeconomic policy had indeed been too loose. However, an advantage of the nominal GDP level targeting framework he favors over inflation targeting is that it doesn’t require distinguishing between supply and demand shocks in this way when formulating policy.

Biden on Corporate Greed Driving Inflation

In a press conference on July 11, President Biden stated:

I’m not anti-corporate. But corporate — corporate profits have doubled since the pandemic — doubled. It’s time things get back in order a little bit.

We got more to go. Working-class people still have — need help. Corporate greed is still at large. There are — prices — the corporate profits have doubled since the pandemic. They’re coming down.

It’s unclear which numbers Biden is referencing—possibly nonfinancial corporate business profits before or after tax (without adjusting for inventory valuation and capital consumption). Regardless, looking at nominal (or money) profits and assuming their rise has somehow caused inflation, as implied, is misguided.

First, in a healthy economy, we’d expect total dollar profits to grow as real GDP increases. This is because economic growth typically leads to higher production and sales, resulting in higher money profits for businesses.

Second, even if there were a correlation between inflation and a more robust measure of corporate profits, it doesn’t mean corporate profit-seeking is *causing* inflation. A better explanation for the simultaneous rise in corporate profits and inflation during the recent period is a third factor: rapid total spending growth on final goods and services, that pushed up retail prices faster than wages.

As we’ve documented extensively, “greedflation”—the notion that corporations suddenly used their power to raise markups and drive inflation higher—is a pernicious myth.