Dear Capitolisters,

It’s been two months since I first wrote about the U.S. infant formula mess, and a lot has happened in the meantime. The Biden administration initiated “Operation Fly Formula” to airlift foreign formula, invoked the Defense Production Act to spur more production here, and tried to relax various FDA rules to encourage foreign producers to enter the previously closed U.S. market. Numerous pieces of congressional legislation have been proposed, with Biden signing one modest one (on administration of federal food assistance) into law. And Abbott Laboratories’ Michigan plant—the one that likely turned a modest formula shortage into a serious crisis—reopened, only to close again because of flooding, and then finally reopen again earlier this month.

Yet the biggest recent formula news may very well be what hasn’t happened in the four-plus months since the shortages really cranked up: a significant improvement in domestic supplies. The Wall Street Journal has the latest:

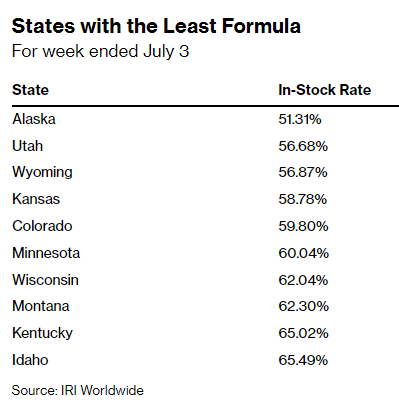

Availability of powdered formula products in U.S. stores earlier this month dropped to the lowest level so far this year, with about 30% of products out of stock for the week ended July 3, according to the market-research firm IRI. While availability improved slightly last week, out-of-stock levels remain higher than in recent months, and shortages remain acute in states including Alaska, Utah and Wyoming, IRI data showed.

At the same time, consumers are finding fewer choices of brands, sizes or formats of formula on grocery-store shelves as the variety of available products shrinks. U.S. supermarkets over the four weeks ended June 26 sold an average of 11 different formula products per store weekly, according to IRI, compared with a weekly average of 24 from 2018 to 2021.

Keith Milligan, controller of Piggly Wiggly stores in Georgia and Alabama, said his stores are carrying five of the 30 formula products they typically sell, compared with about 10 in late spring. Store shelves aren’t empty, but have many gaps, Mr. Milligan said, and customers are purchasing what is available.

“It has not improved at all,” Mr. Milligan said of Piggly Wiggly’s formula supply.

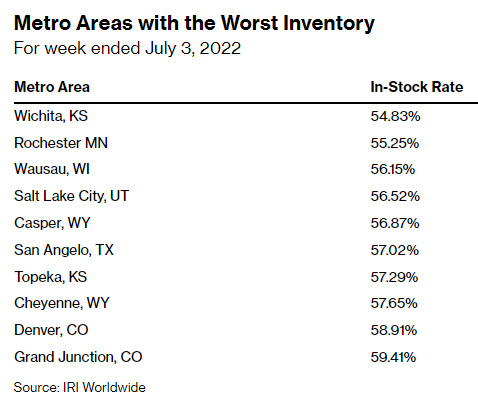

Major online retailers—as cataloged by the unfortunately-still-useful “Baby Formula Stock Tracker” website—also show many products still out of stock. Bloomberg documents where brick-and-mortar shortages have been the worst:

In short, things are a smidge better than they were at the market’s nadir, but we still remain woefully undersupplied several months after this crisis first began.

So What’s Going On?

Several factors have contributed to the continued problems in the U.S. baby formula market. For starters, there’s the simple issue of time: Abbott projects that products made at its Michigan plant will start hitting U.S. store shelves six to eight weeks after its early-July reopening (i.e., late August or early September, assuming no more glitches). There’s also the issue of hoarding, ironically exacerbated by the political drama surrounding spring shortages: The Journal reports, in fact, that “[s]ales surged 52% during a single week in mid-May when President Biden announced efforts to address the shortage but have declined in recent weeks.” (Oops.) But that same report adds that year-to-date formula sales in the United States are up only 4 percent, so hoarding is a minor player overall. Instead, this crisis remains primarily a supply-side issue.

And it’s on that supply side that we continue to see significant policy impediments:

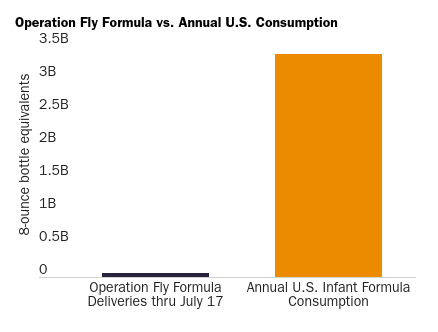

First, Operation Fly Formula has made for some good photo ops, but it’s just not big enough to make a serious dent in the U.S. market. Per the White House, the initiative will have delivered about 55 million 8-ounce bottles of foreign-made formula through July 17. That probably sounds like a lot, but it’s actually less than one week of U.S. formula consumption (65 million bottles). For the innumerate out there (no judgment!), I made a chart to put this all into perspective:

Given this reality, the heavy lifting here remains in the hands of private parties—foreign manufacturers, global shippers, U.S. retail chains, etc.

Only one problem ...

U.S. tariffs, which cover the vast majority of infant formula imports, remain in place. As I explained in my Senate testimony, these taxes average a whopping 25.1 percent, but the restriction is actually worse than that because of how the tariffs are designed, escalating once certain import volumes are reached. Because importers may be on the hook for even higher duties than the already-high base rates at issue (and because they can’t really know whether their shipments will be the ones to trigger the higher duties), U.S. players are further discouraged from importing. Last Friday, the House passed a bill to temporarily suspend these duties through the end of the year, but it’s not yet in effect and doesn’t provide retroactive relief to any imports that have already arrived. Thus, assuming Biden signs this bill or something like it into law, we wouldn’t expect additional formula supplies to arrive until a few weeks thereafter. Until then ... nada.

Finally, FDA regulations continue to be a long-term barrier to sustained import supplies. As the Financial Times reported a few weeks ago,the FDA’s procedural improvements do appear to be encouraging foreign producers to participate in Operation Fly Formula, but they have major limitations (emphasis mine):

Seven overseas suppliers have so far been granted authorisation to import formula under the Biden administration’s Operation Fly Formula, including new entrants Kendal and Bubs, an Australian company. Dozens of others, including Fonterra, the world’s biggest dairy exporter, and its New Zealand rival A2 milk have also applied for approval.

But the waivers allowing them to ship into the US are only temporary and regulators have insisted they will expire on November 14, a move that could force mothers to switch their babies back to formula provided by Abbott. Bubs and Kendal are both pressing the US Food and Drug Administration to grant full approval for their formula following application processes that have been going on for years.

The article then helpfully quotes a European formula executive on the restrictiveness of the FDA’s regulatory requirements and its effect on foreign competition and the U.S. market:

“The US market has always been structurally quite concentrated, and one of the reasons for that concentration is that there are very high barriers to entry,” said Will McMahon, Kendal’s commercial director.

New entrants are required to prove “from scratch” that their products are safe, including through an animal study and clinical study on humans to the regulator’s specific requirements, even if they are already approved for sale elsewhere, he said.

“With any new ingredients you are using, you have to show that they are generally recognised as safe,” he added. “It’s hard to believe but because we use natural milk fats instead of palm oil, the FDA needed us to prove to them that whole milk is ‘generally accepted as safe’.”

According to a June Reuters report, these barriers—even in the temporarily relaxed system—blocked several other foreign applicants from selling here. The latest news is a little more optimistic: The FDA appears to be examining how to keep approved foreign producers in the U.S. market long-term, but its plans remain vague and incomplete and appear to utilize the older, more onerous standards (just maybe helping manufacturers navigate them).

That temporary policy changes didn’t fix U.S. shortages shouldn’t be surprising. As we discussed back in May, high regulatory and tariff barriers—along with the additional distortion of the U.S. market caused by the WIC program’s preferential treatment of a handful of U.S. producers—discourage foreign formula producers from dedicating the ample resources needed to sell here on a consistent basis, even though there was significant demand for their products here. These kinds of trade/regulatory disincentives matter a lot for any product, but they matter even more for infant formula because product reputation matters so much and because the United States is a relatively low-growth market (we’re not having a lot of babies these days, unfortunately). In short, few companies are willing to make a ton of effort to establish a foothold in a stagnant market, and few parents are willing to take a flier on a product they’ve never heard of. These issues—combined with basic logistical impediments like shipping times and plane or warehouse space—mean that, when a crisis hits, the government can’t just flip a switch and suddenly solve the problem. As one U.S. retailer told the Journal, imports were a “a drop in the bucket” when Operation Fly Formula got started, because his “stores don’t have access to overseas supplies.”

Minor problem!

For these reasons, I’ve proposed permanent changes to U.S. trade and regulatory policy to make it as easy as possible for major foreign producers to sell here now and, critically, in the future: nixing tariffs, requiring the FDA to allow formula approved by a competent regulator abroad (instead of “helping” them meet a second layer of difficult rules), fixing WIC, etc. Permanent changes like these are needed to ensure that foreign multinational producers 1) invest in advance in the official sales and distribution channels that would have eased and accelerated deliveries today; and 2) establish brand recognition (especially among doctors) and loyalty to truly diversify the U.S. market and thus reduce the chance of a single, dominant producer collapsing the whole market. Only those kinds of changes will prevent a single plant closure or other domestic shock from cratering the whole market in the future. Indeed, as even the FDA seems to recognize, making it easier for foreign producers to sell here is “creating more resiliency in the U.S. infant formula supply chain and reducing the risk of reliance on too few production facilities supporting the United States.”

Congress, however, seems uninterested in such reforms—and has taken months to simply suspend the tariffs.

Lessons Abound

This congressional inaction and the continued problems in the U.S. market formula are unfortunate, but they do provide some lessons for this product and many others.

First, contrary to a lot of the supply chain rhetoric in Washington these days, the federal government just isn’t very good at predicting where the Next Big Crisis will be and planning in advance to resolve it. As I noted in May, there were signs of a problem brewing in infant formula supply chains months before the Abbott debacle, but—as President Biden himself admitted in June—the issue wasn’t on the White House’s radar until things reached crisis levels (more than two months after the initial Abbott recall). Indeed, even after the White House got involved, customs agents were still seizing “illegal” European formula at the border. These facts reflect not only an understandable lack of a crystal ball to stop crises before they begin, but also a fundamental lack of information (and information-sharing) at various agencies.

Market players, by contrast, were aware of the problems brewing in the formula market and have since been providing granular, almost real-time data on national supplies. Parents aside, most of the private parties involved here aren’t acting out of any altruism or patriotism (or whatever) but because infant formula is an important product to important customers (new families are big future bucks!), and the grocery business is a fiercely competitive, low-margin industry where detailed inventory data are absolutely essential to attracting and keeping customers (and thus turning a profit). The substantial, widely available baby formula data contrast favorably with another essential good that was also once in short supply but not primarily distributed at the private, retail level—personal protective equipment. There, various government efforts to map national inventories and manage supplies and distribution across jurisdictions never really succeeded (and problems were still popping up in 2022). It was even worse at the Veterans Administration, where—per the Government Accountability Office—“[l]ong-standing problems with its antiquated inventory management system” exacerbated PPE challenges during the pandemic.

(And don’t even get me started on how Texas grocery chain H.E.B. saw the pandemic coming months before Washington did.)

Second, even after the government does identify a crisis, it can be achingly slow to adapt policy accordingly. This stasis is exacerbated where solutions require repealing or substantially changing existing government interventions in the economy—once enacted, they are exceedingly difficult to dislodge, even in an emergency. In the case of formula, it’s now been four months since the crisis really ramped up, but Congress still hasn’t approved even temporary tariff relief, even though—If my June Senate hearing, recent House/Senate votes, and widespread media coverage are any indication—there’s broad, bipartisan support for importing more formula to ease current shortages. As the Financial Times and Reuters stories above indicate, moreover, private actors are eager and willing to ease U.S. shortages—if the federal government would only let them.

But it won’t.

Some of this congressional inaction is by constitutional design and some is because Congress has increasingly become a debate/tweeting society instead of a legislative body. However, policy inertia is also surely to blame: The current trade, regulatory, and WIC systems have been in place for decades, and both bureaucrats and private beneficiaries (e.g., protected formula makers) have a strong incentive to oppose systemic reforms. And oppose them they are: As one domestic producer hilariously told the FT, “There are no barriers to entry in the US market whatsoever ... So long as you can meet the formula requirements of the FDA and you subject your brand to the safety and quality requirements, then you can enter the US market.”

You get that?

Combine industry and regulatory opposition with the simple political aversion to getting blamed for acting (usually far more than for not acting), and what should be a relatively easy reform with wide support becomes a very tough nut to crack, even in the middle of a legitimate national crisis caused in large part by the bad government policies targeted for reform! This bodes ill for not only infant formula but plenty ofother products—such as sunscreen or monkeypox vaccines or solar panels or other tariffed goods—that are suffering from similarly nonsensical and harmful government impediments.

Both lessons argue for less government micromanagement of domestic and global supply chains, and for more efforts to eliminate existing government restrictions on companies and individuals doing what they already have tremendously powerful incentives to do and are really good at doing. Indeed, a new book from Brookings economist Clifford Winston reviews hundreds of academic studies of various government interventions to “fix” markets and finds that, in general, “an expansion of markets, not their curtailment, would better deliver on our widely shared political goals of improving material living standards, broadening opportunity, and protecting families from unforeseen hardships.” (Read the whole review for examples.) Thus, reforms should include not only repealing dumb tariffs or antiquated regulations that distort markets for essential goods and services and imperil long-term national resiliency, but also installing in the remaining laws/regulations “sunset” or similar provisions that would make it easier for policymakers to overcome the inevitable policy inertia and special interests that those economic interventions create.

Otherwise, we’ll remain burdened by policies that raise costs, reduce choices, and foment economic fragility—even after four months of empty baby formula shelves.

Capitolism will be off next week, but—if you really need a fix—I’ll surely be tweeting random stuff from the beach.

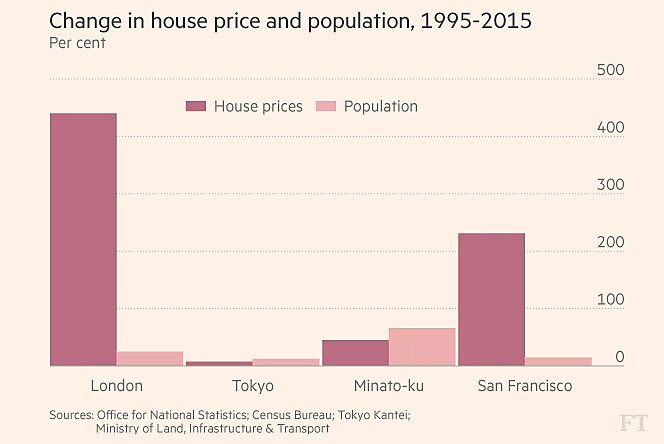

Chart(s) of the Week

The Links

Me, on the shrinking economic case for federal semiconductor subsidies

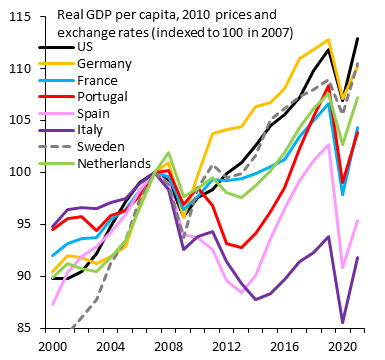

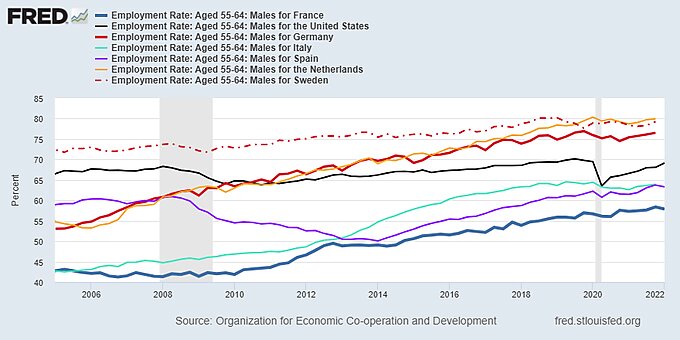

The dynamic U.S. labor market has outperformed the static European one since the pandemic hit (related)

“No, the global economy is not breaking into geopolitical blocs”

California’s AB5 is a mess for the trucking industry

Jones Act lobbyists want to “Jonesify” U.S. offshore energy facilities

Colorado licensing boards won’t penalize license applicants for out-of-state marijuana convictions

To-go alcohol probably hasn’t increased alcohol-related driving deaths

“Inflation Has Outpaced Wage Growth. Now It’s Cutting Into Spending.”

Chemical fertilizers, global farm production, and environmental protection

Sheetz and Tesla partner up for major EV charging station network (GM has similar plans)

More signs of supply chain stresses easing in the U.S.

China risks hard landing in housing

China’s recent struggles with foreign talent

On mechanization and employment

The chip boom is over, and a glut may be on the horizon (perfect time for subsidies!)

Futuristic Swiss tunnel project is 100 percent privately funded