After an Alaska Airlines flight experienced a harrowing—but thankfully not fatal—midair door blowout earlier this month, the U.S. aircraft manufacturing behemoth Boeing has faced renewed scrutiny over the safety of its 737 MAX plane. As the Wall Street Journal reported, the episode was “the latest in a string of quality problems at Boeing,” which include two fatal crashes of Boeing’s smaller 737 MAX jets back in 2018 (in Indonesia) and 2019 (Ethiopia). Other reports have swirled about how this latest incident raises big questions about not only the 737 MAX, but also Boeing’s entire business model and the main U.S. regulatory body (the Federal Aviation Administration) responsible for the planes’ safety.

It’s far too early to say if this is a full-blown scandal at Boeing or the FAA (though the latest news doesn’t seem great!). And I won’t for a second claim to know what exactly led to Boeing’s 737 MAX problems, or whether any malfeasance or crimes (by either executives or federal regulators) took place. But if a scandal does materialize in the coming days, it wouldn’t exactly be a huge surprise—and not just because of Boeing’s recent history of technical problems.

Indeed, if you know anything about Boeing—and the deep history of corruption involving government-backed companies (especially “national champions”) around the world—the only real surprise here is that the whole shebang didn’t come crashing down even sooner.

The Long, Sordid Relationship Between Big Government and Big Business

On one hand, it’s just common sense that cronyism and corruption concerns might arise at a giant company making a heavily regulated product and benefiting from massive amounts of government support (subsidies, contracts, etc.). Regardless of the merits of that regulation and support, the sheer amount of taxpayer and corporate money involved, as well as the political and bureaucratic processes required to obtain it, make some amount of cronyism all but inevitable. (Incentives matter!) And, as we’ve discussed with Big Steel, Big Ship, Big Sugar, and their corporatist friends, it’s often simply cheaper and easier to hire lobbyists and use the political process to pad your bottom line than it is to compete and innovate in a relatively free market.

But the corrupting effects of government on corporate behavior aren’t just common sense—they’re backed by decades of scholarship in the United States and abroad. In a 1997 paper, for example, economists Alberto Ades and Rafael Di Tella examined 32 countries and found that ones with “active industrial policies” (e.g., government procurement preferences and subsidies to Japanese and South Korean “national champions” during the latter half of the 20th century) were more likely to suffer from corruption, which in turn undermined the efficacy of the industrial policies at issue. More recent work found that EU development subsidies and procurement contracts substantially increased corruption risks in Eastern Europe in the 2000s, and that public procurement (and the sectors, such as transportation and construction, closely tied thereto) is disproportionately vulnerable to corporate corruption problems.

Similar findings hold for tariffs and other kinds of protectionism. In a 2009 paper, Pushan Dutt and colleagues examined numerous trade and industrial policies during the 1990s and found “strong evidence that corruption is significantly higher in countries with protectionist trade policies”—a problem amplified when bureaucrats are granted wide discretion in implementing the interventionist policy at issue. Elsewhere, Aneesh Raghunandan found that U.S. companies receiving state-level subsidies, especially tax breaks, are more likely to engage in financial fraud than are nonrecipient firms—a result likely driven by “lenient” enforcement in subsidy-providing states.

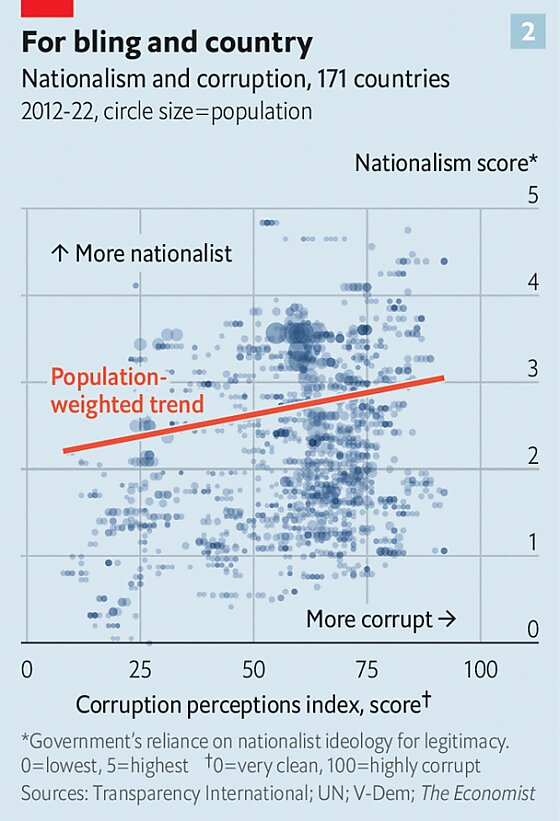

More broadly, The Economist found last year a statistically significant relationship between a country’s level of nationalism and both its perceived and actual level of corruption:

(Though they are of course right to note that “more nationalist government does not automatically mean a more corrupt one.”)

Regulation can corrupt, too. Randall Holcombe and Chris Boudreaux’s look at Scandinavian countries, which had big welfare states but lower regulation and lower corruption, discovered a “strong relationship between the amount of government regulation in a nation and the level of corruption in that nation.” By contrast, academics have found that freer-market policies seem to have the opposite effect. Analyzing data from the mid-to-late 1990s, for example, economists John Gerring and Strom Thacker found that “open trade and investment policies and low, effective regulatory burdens do correlate with lower levels of political corruption.” Dutt (above) found much the same. Others have too.

Of course, one needn’t dig through piles of studies to notice that government-preferred corporations and their regulators can be prone to scandal. As Tad DeHaven and Adam Thierer recount, for example, the U.S. military “procurement and contracting for everything from big-ticket weapons programs to foreign nation-building has been littered with rent-seeking, cost overruns and sometimes outright corruption.” Non-defense companies enjoying government support often run into similar problems at the federal and state level, as do the government actors doing all that supporting.

Import-protected companies colluding (allegedly) against American consumers and taxpayers? Well I never. https://t.co/TfDhMaQnVw pic.twitter.com/JiAfHDSo4v

— Scott Lincicome (@scottlincicome) May 24, 2023

Examples abound outside the U.S. too. As the Mercatus Center’s Veronique de Rugy reported last year, the heavily subsidized European planemaker Airbus “got hit with a $3.9 billion fine in 2020 for using hundreds of intermediaries to bribe public officials in numerous countries—including Japan, Russia, China, Libya, and Nepal—to buy its planes and satellites,” and “also faced an American inquiry over possible violations of export controls.” Corruption at the company—which is Europe’s “national champion” and Boeing’s biggest rival, by the way—was in the words of a U.K. regulator, “endemic,” and the decades-long bribery scandal has since become a “case study” in corporate fraud. At the time of the announcement, the Guardian reported, the Airbus anti-corruption settlement had become the U.K.’s biggest ever, topping the previous No.1: British national champion Rolls-Royce, which enjoyed broad U.K. government support and then succumbed to its own government contracting scandal.

In Korea, subsidized national champions—family conglomerates called “chaebols” (Samsung, LG, Hyundai, etc.)—have long been embroiled in corruption scandals which have dragged down not only their financial performance but also the Korean economy and political stability. Corruption and cronyism have also plagued another 20th century Asian industrial policy champion: “Japan, Inc.” As one paper put it, the “close government-business nexus” in Japan “creates corruption, especially at a high level of administration.” Economist Marcus Noland further found that Japanese government subsidies went predominantly to politically organized sectors and politically important areas, and that “corruption was encouraged by the policy-instigated creation and distribution of rents.” Scandals have continued in the following decades.

Taiwan’s past industrial support has also raised cronyism concerns (albeit to a lesser extent than in Korea, it seems). And just yesterday, Bloomberg reminded us that Brazil’s industrial policy experiment in the 2000s ended with “corruption scandals” involving then-president Luiz Inácio “Lula” da Silva and his successor, Dilma Rousseff. (Now back in office, Lula is trying industrial policy again. I’m sure it’ll all go swimmingly.)

When all’s said and done, however, there may be no better example of industrial policy’s corruption problem than China. There, both state intervention in the economy and corruption are widespread—and, as detailed in a 2022 documentary, undoubtedly related: “The Chinese government has a lot of say in the economy because it owns almost all the land, natural resources and banks. Officials, in turn, have enormous power to pick winners and losers at their whim, leaving a lot of room for corruption.”

One of the biggest—and certainly most notable—scandals in this regard recently took place in China’s semiconductor industry, where numerous government and corporate officials “disappeared” following an investigation into China’s “Big Fund”—a web of government and state-owned corporations dedicated to delivering tens of billions of dollars to local chip companies to achieve both bleeding-edge technology and national self-sufficiency. Instead, the fund delivered mainly waste and graft, forcing China’s Xi Jinping to demand an overhaul of Chinese industrial policy policy:

Xi’s calls for innovation co-ordination at higher levels of government came after a string of disastrous venture capital-style investments in regional chipmakers by local governments and allegations of corruption at the National Integrated Circuit Industry Investment Fund, a key player in China’s semiconductor strategy.

The NICIIF had generally sought to balance policy goals with investment returns, reinvesting profits across the industry. But it had come under criticism for frequently funding low-cost and profitable chip design companies while failing to help higher-end Chinese chip manufacturers catch up with Korean, Taiwanese and other foreign rivals.

China’s industrial corruption problems certainly aren’t limited to chips. They also plague Chinese sectors like housing, tobacco, banking, and infrastructure, where state actors dominate. This includes, as we discussed just a few weeks ago, military procurement, where “corruption inside China’s Rocket Force and throughout the nation’s defense industrial base is so extensive that US officials now believe Xi is less likely to contemplate major military action in the coming years than would otherwise have been the case.” One recent paper used Chinese housing records to estimate the full extent of Chinese corruption last decade, and the results were jaw-dropping: About 13 percent of Chinese government officials had “unofficial income” (hint, hint) that was on average almost as much as their official income (83 percent). Just as damning, this unofficial income increased in line with the official’s rank and power of his government bureau.

China is, to its very partial credit, trying to clean this all up. But, as the Financial Times noted back when the Big Fund scandal first broke, tamping out corruption will be difficult, if not impossible, as long as the state is heavily involved in the economy:

Yuen Yuen Ang, author of China’s Gilded Age, believes that the “root cause” of corruption in China stems from the state’s enormous influence over the economy.

Particularly susceptible, Ang said, were the 1,800-plus government guidance funds that act like the Big Fund.

The combination of “mega transactions, complex financial instruments and the lack of transparency and accountability may present fertile soil”, Ang said.

Good luck weeding that garden, comrades.

And That Brings Us Back to Boeing

So what does this all have to do with Boeing? Well, contrary to what you might read on the internet (lol), Boeing is not some “free market” creation and instead has a long and well-documented history of being supported by and intertwined with the U.S. government. In fact, free marketeers have long seen the company as a poster child for federal corporatism and crony capitalism, particularly as it relates to the Export-Import Bank, which provides subsidized financing for U.S. exports. De Rugy provided some of the gory details last year:

- According to Executive Gov, “in 2021, 49% of [Boeing’s] revenue” — $23 billion worth — “came from the federal government.”

- Boeing receives loads of tax breaks and infrastructure support from state and local governments.

- For decades, Boeing was the biggest beneficiary of the Export-Import Bank, so much so that much of Ex-Im’s Covid response was designed with Boeing specifically in mind.

- Boeing’s commercial sales are often brokered by the U.S. government. For example, Air India’s recent order of over 200 Boeing jets was announced by President Biden. President Trump announced Qatar’s purchase of five Boeing 777 freighters in 2019. President Obama was present when Vietjet Airlines signed a deal to purchase 100 Boeing 737 MAX airplanes, and he even once quipped that he deserves a gold watch for selling so many Boeing planes.

- Boeing moved its headquarters to the Washington, D.C., area when existing tax subsidies in Chicago ran out. Also no doubt contributing to this move was Boeing’s recognition that its future depends mightily on government appropriations and the favor of regulators.

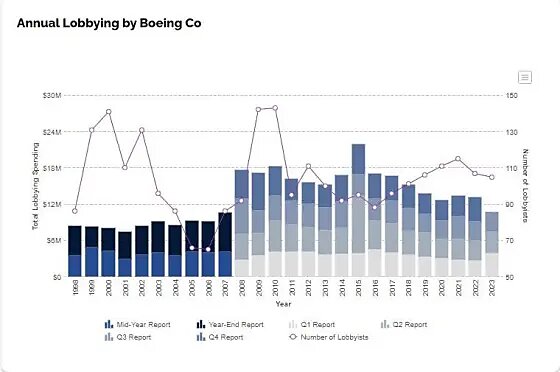

Boeing’s lobbying operation, meanwhile, is as massive as you’d expect, with more than 100 lobbyists on payroll and a budget of more than $10 million per year:

The influence peddling also extends to the company’s subcontractors, including the one—Wichita-based Spirit Aerosystems—at the center of the latest 737 MAX controversy. That company is now run by Patrick Shanahan, who was Donald Trump’s acting defense secretary and faced “an ethics probe into allegations of favoritism toward the aerospace giant.” Trump literally once referred to him as “the Boeing guy” in public.

All this cronyism, it should be noted, is a rare bit of left-right agreement among D.C. policy wonks (though of course everyone disagrees about whether this issue demands more or less government involvement). Writing in The American Prospect, a progressive publication, Alexander Sammon in 2019 called Boeing “an adjunct of the state”—one that received more federal money than all but one U.S. corporation (Lockheed Martin) and even many government agencies, including the Environmental Protection Agency and the Department of the Interior. He’s certainly not alone on that side of the aisle.

Sammon, de Rugy, and others also seem to agree that Boeing’s connections to and support from the government may be to blame (at least in part) for the 737 MAX’s continued problems. As de Rugy documented last year, “Boeing got Congress to change the law and reduce the safety standards applied to the as-yet-uncertified newer variants of the 737 MAX. The company’s cozy relationship with its regulators has also played a role in the 737 MAX’s catastrophic crashes.” Sammon, meanwhile, says that all this corporatism fomented a “weakened regulatory environment” that certified the jets and kept production lines humming even as internal problems mounted. Others have similarly warned of federal regulators being “captured” by Boeing due to their close working relationship across various agencies. Here’s how Bloomberg investigative reporter Peter Robison, the author of Flying Blind: The 737 MAX Tragedy and the Fall of Boeing, described it to Bloomberg podcaster Tracy Alloway:

Tracy: What about the FAA, the Federal Aviation Administration? So I don’t think we can have this conversation about the incentives and the structure of the system that created this bad outcome without talking about the relationship between Boeing and the FAA.

Peter: Yes, because that turned out to be a bad relationship. The FAA, especially the FAA management, began to see its role as helping Boeing in its goal of delivering airplanes. And the incentives for managers became almost to see the aircraft industry as the customer rather than as the regulated entity. You know, I wrote about many cases in my book where the FAA manager in charge of monitoring Boeing would then go on to get a job at Boeing or at the industry lobbying group. So that problem with the revolving door is there.

Even NPR recently came to this same conclusion, noting that Ex-Im subsidies and other government support for Boeing undergirded the “cozy ties” between the company and U.S. regulators—ties that, per various experts they interviewed, may be partly to blame for the 737 MAX’s continued problems.

Summing It All Up

None of this is to argue that Boeing management and corporate policy don’t deserve some of the blame for the company’s longstanding problems. Nor is this an argument against any and all government involvement per se.

But the well-documented experience of the United States’ aircraft “national champion”—and of the government agencies supposed to keep it in check—does raise another, lesser-discussed concern about all the tariffs, local content mandates, procurement preferences, and trillions in taxpayer subsidies that the United States government is today doling out to boost the competitiveness of certain strategic industries and the U.S. economy more broadly. As PIIE’s Adam Posen wrote last year, citing Boeing and Airbus as his prime examples, “history shows that rather than converging on best practices, or at least putting useful competitive pressure on domestic industries, subsidy races lead to a perpetuation of corruption” that “stifles innovation” and generates other economic harms that undermine the subsidies’ main objectives.

Thus, Ades and Di Tella find in their 1997 paper that industrial policies’ corrupting effects can reduce their investment-boosting potential by around half. A contemporaneous review of cronyism in Korea and Taiwan suggested much the same, cautioning that, without “more effective safeguards against policy capture” than found in even those famously competent governments, any indirect benefits (“positive externalities”) arising from industrial policy “will need to be very large indeed to repay the cost of infant-industry support.” Or, as World Bank economists warned in 2020 regarding these and other costs, “industrial policy can do more harm than good to markets and overall welfare.”

Yet, more often than not, industrial policy advocates and their fancy calculations of economic gain consider few, if any, of these risks—until it’s too late.

As I explained a couple years ago, we tend to tolerate these risks for national defense because we don’t really have a choice: The government is the sole consumer of military goods and has unique knowledge thereof. Furthermore, the public legitimacy and importance of the government’s overall mission isn’t really in doubt, thus reducing potential politicization and short-termism. Of course, corruption and other U.S. military procurement problems still arise and reforms are still necessary. But the inevitable messes and costs that materialize in the defense space are in many ways the price we have to pay for having battleships, fighter jets, tanks, and other cool/deadly stuff our armed forces need (or, at least, say they need). So, maybe some of the problems facing a huge military contractor like Boeing and related federal regulators are unavoidable.

But for the company’s commercial products, as well as all the other subsidized and protected products with few if any defense-related applications, there’s no such excuse.

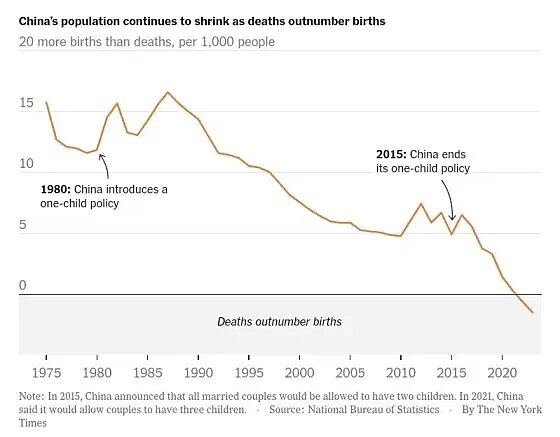

Chart(s) of the Week