That shock, of course, materialized when an Abbott Labs factory in Michigan was shut down for possible contamination issues, leading to extended periods of empty store shelves, panicked American parents, and frantic efforts by the federal government to alleviate the crisis.

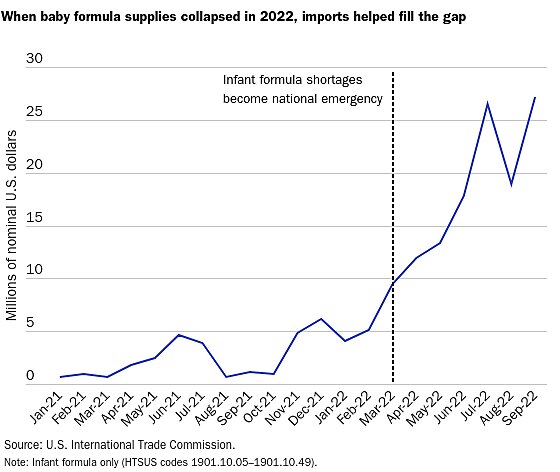

Imports Helped Save the Day

As we discussed in July, imports were a big focus of the feds’ efforts. Via “Operation Fly Formula,” President Joe Biden commissioned military planes to fly in formula from Europe—more a photo op than a real improvement in the domestic supply situation but still a very visible acknowledgement of imports’ value (and protectionism’s problems, especially when a crisis hits). More important, Biden instructed the FDA to exercise its “enforcement discretion” to fast-track temporary approvals of certain foreign formula brands, so they could sell here without the well-supported fear of having their shipments seized at the border. The FDA ended up issuing temporary authorizations to a handful of foreign producers (mainly in Europe, the U.K., Australia, and New Zealand)—“creating,” in its own words, “more resiliency in the U.S. infant formula supply chain and reducing the risk of reliance on too few production facilities supporting the United States.”

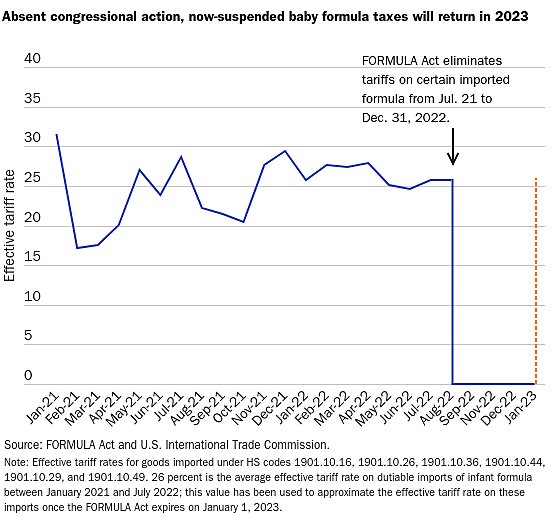

After much delay, Congress also acted, with the near-unanimous July passage of the hilariously named FORMULA Act (look it up!), which temporarily suspended all tariffs on infant formula through the end of 2022. Finally, the FDA in September recognized the need to keep these players in the U.S. market to ensure U.S. inventories remain stocked, so the agency extended the authorizations through October 2025.

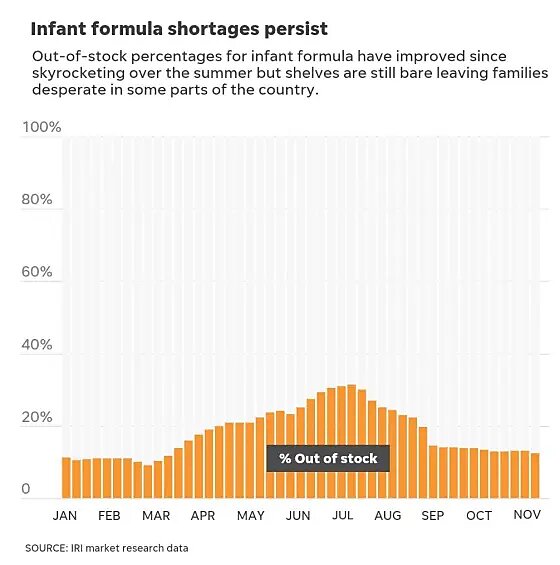

As I’ve noted repeatedly, this is not ideal policymaking—deeper and more durable reforms of both international and domestic policy are needed—but it was at least something. And it was a clear recognition by the executive and legislative branches that freer trade could help stabilize the U.S. baby formula market and, more importantly, keep American babies healthy and fed. And the chart below shows that the government’s efforts did indeed boost imports—something the White House also acknowledges. (Per Reuters last week, “[n]ew brands have increased formula supply this year, with multiple foreign brands available on shelves and online, including Danone’s Aptamil and Bellamy’s Organic, a White House official said.”)