Dear Capitolisters,

How U.S. Air Travel Can Get (a Little Of) Its Groove Back

The causes of our travel woes are many and varied, but U.S. policy is making things worse.

I’ve been traveling a lot this year—a lot. And it hasn’t exactly been a fun experience (though I’m of course happy to trade the relative tranquility of 2021 air travel for a more open, but chaotic, 2022). Indeed, judging from the news and my own personal experiences, it’s as if everyone in the United States rescheduled their 2020–2021 personal and professional events for a 12-week period in 2022. Seriously, folks, it’s kinda nuts out there right now.

Anyway, a lot of the chaos we’re seeing seems to be the usual pandemic story: Most airlines shut down routes and furloughed workers when the pandemic first hit, and they’re all now struggling to resume more normal operations now that everyone’s traveling again, more quickly than the airlines anticipated. This struggle appears particularly rough on the labor side, with industry folks complaining about a lack of pilots, mechanics, air traffic controllers, and so on—and it’s been exacerbated by the usual spring/summer weather disruptions and pandemic problems in supply chains and support services.

Put it all together, and you have a recipe for a bunch of discrete flight cancellations and overbooked replacements (which are bad enough), and broader, more systemic challenges facing the future of U.S. air travel: fewer flights, fewer routes, higher fares, etc. But, like so many problems we’ve experienced during the pandemic, the ones facing American air travel aren’t solely pandemic-related. Instead, once again, there’s U.S. policy—in this case, air “cabotage” restrictions—likely making everything worse.

You may recall that we’ve already discussed maritime cabotage laws—namely, the Jones Act, the Foreign Dredge Act, and the Passenger Vehicle Services Act—and the harms that these protectionist laws inflict on the U.S. economy. Well, unfortunately, we have similar restrictions for air passenger and cargo service, and—surprise!—they’re causing similar problems.

The (Partial) Success of Airline Deregulation

Before we get to that, however, it’s important first to note the unmitigated successes of past U.S. airline deregulation in the 1970s—eliminating federal control over fares, routes, and market entry for both passengers and cargo—and in the process debunk the all-too-common myth of a “Golden Age” of mid-20th century air travel. A 2014 paper from George Mason University’s Kenneth Button provides a great summary of deregulation’s substantial gains for U.S. consumers and the market more broadly:

The deregulations of the U.S. air cargo market in 1977 and of scheduled passenger services in 1978 delivered considerable, almost immediate, net benefits to the American economy. The gains came in various forms, including lower real fares, more fare choices, more services, and more route options, with the result that the number of air travelers rose from 250 million in 1978 to 815 million in 2012, 736 million of them domestic. As for the effect at the micro level, a study by the American Air Transport Association in 1983 found that air fares in the new, deregulated environment had fallen by 67 percent compared to the levels the old regulated regime would have imposed. Looked at another way, over a full business cycle, the inflation-adjusted 1982 constant dollar–yield for airlines fell from 12.3 cents in 1978 to 7.9 cents in 1997, making airline ticket prices almost 40 percent lower over the cycle. Even those living in small communities that had been the subject of forced cross-subsidization under the pre-1978 regulatory regime benefitted. While the number of small community flights was cut by over 25 percent between 1970 and 1975, the flexibility and innovation stimulated by a freer market led to more such communities receiving non-stop air services in 1983 than in 1978. Added to this, the labor force enjoyed more job opportunities; the number of workers in the industry grew by 30,000 within two years of deregulation.

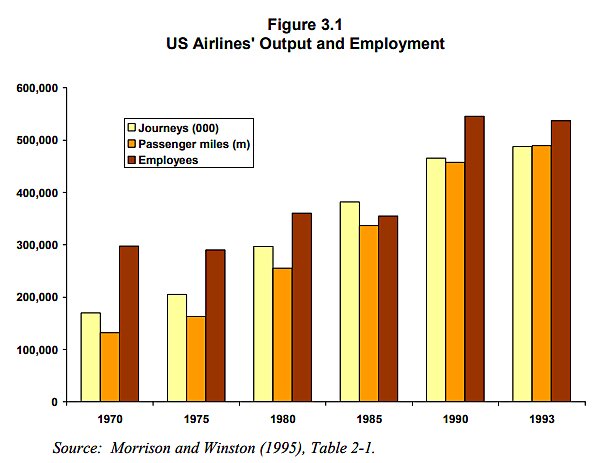

A summary of the literature by NERA economic consulting confirms deregulation’s economic benefits, namely: new market entrants, lower fares, higher productivity, more jobs, expanded services, and more passenger miles flown:

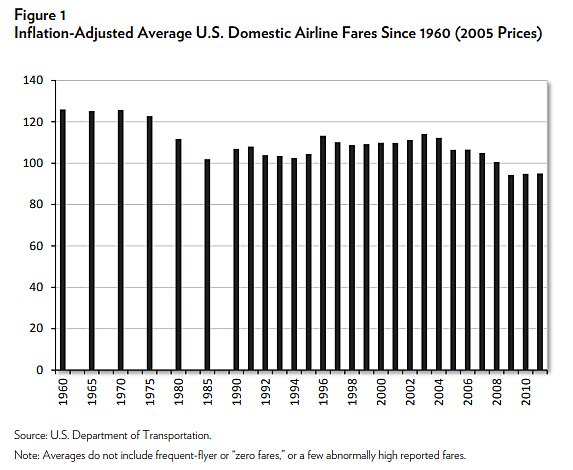

Deregulation’s effect on domestic airfares is probably the biggest benefit of them all, and Button’s companion paper provides the (obviously necessary) chart:

Contrary to popular belief, moreover, these fare benefits have continued over the last decade. According to the Wall Street Journal’s Scott McCartney, for example, the average domestic airline ticket cost $482 (adjusted for inflation) in 1996 but only $260 last year, and “for the 26 years [the U.S. Department of Transportation] has been keeping track based on a 10% sampling of tickets, tickets have been in a pretty narrow band of $300 to $400, not adjusted for inflation.” He also explains that add-on fees for baggage and other things, while significant for airlines’ bottom lines and surely adding a few bucks to passengers’ all-in price, haven’t changed domestic fares’ overall (downward) trajectory—in part because a lot of people don’t pay them. Other analyses, such as economist Jeremy Horpdahl’s examination of non-stop flights from New York to Los Angeles over time, show even bigger price reductions, and—as he notes—it’s all much, much safer today. He thus concludes:

For the typical travel, a middle class person just looking to get from point A to point B without dying, flying is significantly cheaper than it was in the past. For the rich, those who must have the first class experience, there hasn’t been much improvement in terms of prices! The market serves the masses. And the masses have really taken to flying: the number of people flying in the US (2019, pre-pandemic) was about 10 times greater than the mid-1960s. But the US population hasn’t even doubled since (up about 70%). More flights, more passengers, lower prices, and safer travel. That’s the history of flight in the US since the so-called “golden age of flight.” I would argue that the true Golden Age is right now.

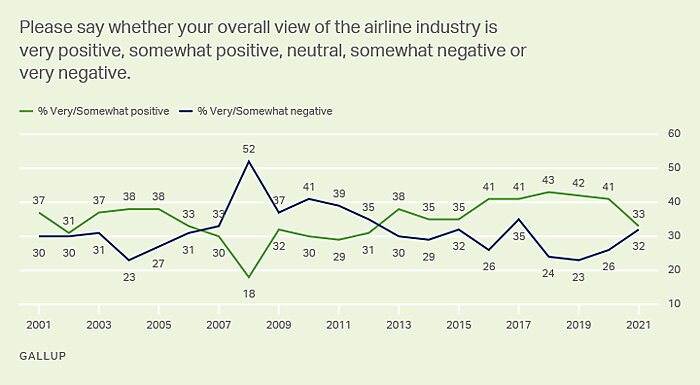

We were all much happier with airline service last year, but that’s almost certainly because flights were emptier and the airlines suspended all those annoying fees and rules to deal with pandemic-uncertainty and to pry Americans from our homes and Zoom calls. But if the news and my recent experiences are any indication, I’d expect Americans’ opinions of airlines to fall back to earth (no gruesome pun intended!) in 2022.

As Button explained, moreover, there’s been a relatively recent reversal of deregulation’s multidecade increase in route availability and, via consolidated “hub-and-spoke” systems, total U.S. destinations:

The largest 29 airports in the United States lost 8.8 percent of their scheduled flights between 2007 and 2012, but medium-sized airports lost 26 percent and small airports lost 21.3 percent. The number of seats available has fallen faster than the seat-miles available, while the average return flight distance has risen from 2,279 miles in 2007 to 2,319 miles in 2010, and to 2,356 miles in 2013. This latter feature is largely a manifestation of the major carriers reacting to higher fuel prices, which have greater proportional effect on short-haul costs.

As the Journal noted a couple weeks ago, trends in route consolidation have been exacerbated by the pandemic and related issues like high fuel prices (which can make less-traveled “niche” routes cost-prohibitive). As they note, “Thirty airports in the continental U.S. have lost at least half the departures they had in 2019”; major airlines like United have pulled out of numerous small markets; and regional carriers have been canceling flights because they can’t find workers. This has forced smaller airports to pay airlines to maintain service or to pursue discount carriers and startups to replace the airlines that left. The Transportation Department, meanwhile, is forcing carriers to service certain small communities and subsidizing them and replacements via the Essential Air Service program, which was “established after the deregulation of the airline industry in 1978 to ensure commercial carriers wouldn’t abandon small communities.” Per this and similar reports, these systemic problems are expected to continue through next year (at least).

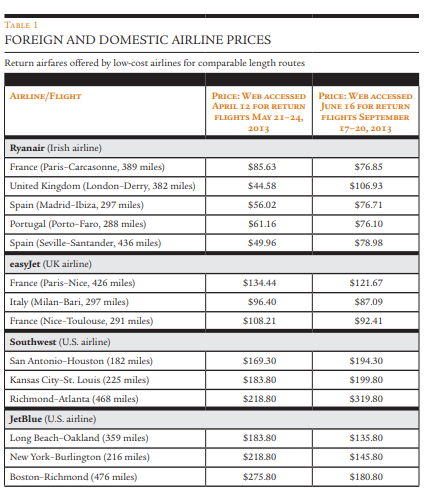

Finally, while domestic airfares may remain low by historical standards, they’ve increased a lot this year (less supply, more demand, etc. etc.) and are high by international standards. For example, a midweek, roundtrip/nonstop September flight from Paris to Berlin runs as little as $75, while the cheapest similar flight going about the same distance in the United States—say, Atlanta to D.C.—is about $50 more. Travel site Kayak’s average fares show a similar difference ($155 versus $203, so about 25 percent less in Europe than the U.S.). Button’s comparison from a few years ago does the same:

Cabotaged, Again

And this is where “cabotage” comes in. In particular, U.S. law (49 U.S.C. § 41703) prohibits the commercial transportation of persons, property, or mail between any two points in the United States in any aircraft that’s not owned and operated by a U.S. individual or corporation. This is essentially a “Jones Act” for commercial airlines and air freight, except that the planes can be made abroad (allowing for Airbus, Embaer, and other planes) and crewed by non‑U.S. citizens (though obviously our dumb immigration restrictions apply there, unfortunately). Federal law also—tellingly—has made exceptions to these rules for Alaska and, until recently, Puerto Rico to ensure that these remote U.S. destinations still have air service. (The former exception has made Ted Stevens Anchorage International Airport the fourth-largest airport in the world, in terms of cargo handled, and second-largest in the United States. Hooray, trade.)

A lot of countries have air cabotage restrictions, which are generally allowed under World Trade Organization rules, but that doesn’t mean they’re a good idea. As Button explains, “incumbent U.S. carriers are being protected from the full force of competition in the same way that U.S. manufacturing firms were in the 1970s, when their costs drifted higher than international competitors and their products became inferior.” Put another way, we have today a mediocre “Big Four” airline oligopoly today (American, Delta, Southwest, and United) much like we had a dominant “Big 3” in the 1980s U.S. car market—blech. Button adds that other markets, particularly the EU, have overtaken the United States in terms of both air service (e.g., hub-and-spoke versus “the radial networks of Ryanair in Europe”) and cost savings. But, unfortunately, those innovative carriers aren’t allowed here.

Eliminating cabotage restrictions would, of course, change that—with all the benefits that competition usually provides. The price comparisons above show the cost-savings potential (which is great), but the bigger deal here might very well be the type of service offered by new international competitors, as it’s precisely what the U.S. market needs right now:

[T]he types of service that Ryanair and some other foreign carriers specialize in match the types that have largely been reduced in the United States. The average Ryanair return passenger trip, for example, is slightly over 1,000 miles. Despite the natural “gap-filling” role they could serve, the European carriers are not, however, permitted to offer their brands of service on this side of the Atlantic. Of course, travelers may not accept them (but many said that about Southwest 35 years ago), or domestic carriers may be stimulated to retaliate and offer comparable services, but either way customers would have a choice if cabotage were permitted.

Button adds that, unlike some failed U.S. low-cost carriers like Independence Air, many discount foreign carriers have “deep pockets,” as well as large, modern, and fuel-efficient fleets. They’d thus be more formidable and long-lasting competitors in the U.S. market.

Recent experience and academic research support these general conclusions about the benefits of eliminating U.S. air cabotage restrictions. Most obviously, Europe in the 1980s and 1990s eliminated national monopolies and all commercial cabotage restrictions for European airlines operating within other EU countries, and then extended this access to non-EU countries Norway, Iceland, Switzerland, and potentially others in the region. The result, as Button noted, was not merely new airlines and lower fares (which subsequent academic research confirms), but also “a 120 percent increase in intra-EU routes between 1992 and 2008 (with an associated increase of 320 percent in the number of routes with more than two competitors),” as well as “moves to commercialize and improve the efficiency of both airports and air traffic control systems through privatization and corporatization—measures that have been pursued less enthusiastically in the United States.”

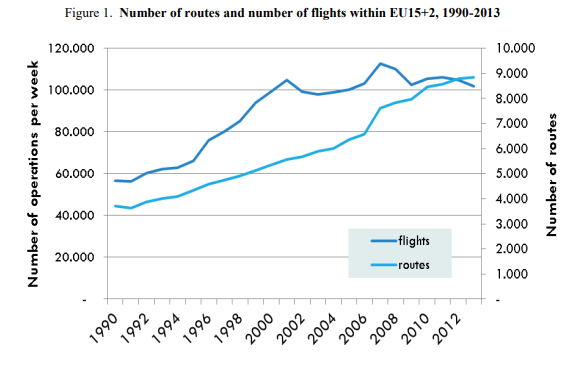

A subsequent OECD Discussion Paper provides some great charts showing this increase in pan-European service, in terms of both the number of flights and routes…

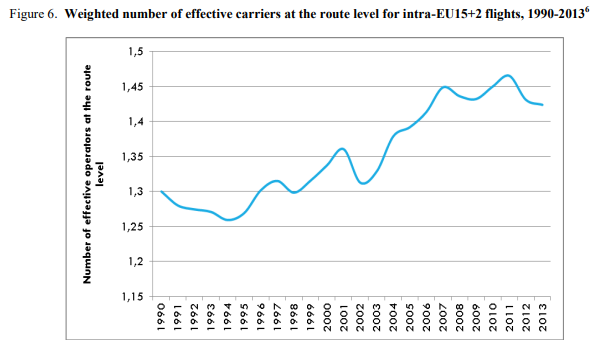

…and the number of carriers per route:

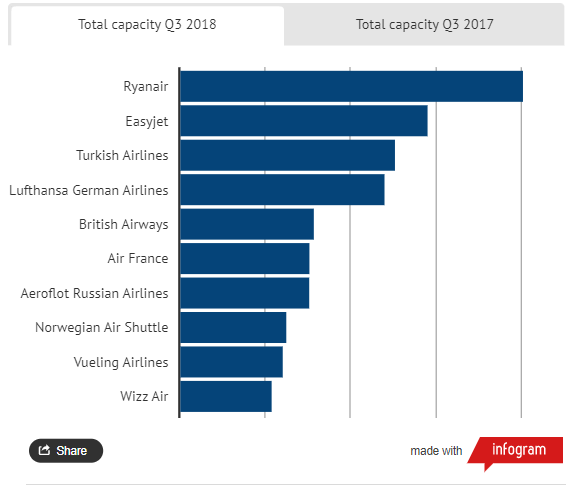

Today, the European market features not only big legacy carriers like Air France and Lufthansa, but also many innovative low-cost and “ultra-low-cost” carriers, such as Ryanair, EasyJet, Norwegian Air Shuttle, WOW Air, and Wizz Air. These airlines have low prices, lots of fans, and (unsurprisingly) tons of capacity:

The United States’ own experience with international air travel provides further support for nixing U.S. air cabotage rules. In particular, various U.S. “open skies” agreements—which allow signatories’ airlines to provide cross-border services to each country—have been found to “have generated at least $4 billion in annual gains to travelers and that travelers would gain an additional $4 billion if the US negotiated agreements with other countries that have a significant amount of international passenger traffic.” Just imagine the gains if we did the same for our domestic market, which handled more than three times the passenger volume in 2019.

Based on these experiences, several papers have estimated the effects of air cabotage liberalization in the United States and have found substantial benefits for American travelers. For example, a 2020 paper calculated that a single European carrier’s entry into the U.S. market would boost American travelers’ welfare by $1.6 billion per year, and that these initial quantitative gains would “expand greatly under a more comprehensive cabotage policy that allows entry by other foreign carriers” (as opposed to just one European company). They also note that new competition would generate the qualitative benefit of increasing service to underserved markets—again, just what the U.S. needs right now. A separate 2019 paper found that U.S. cabotage restrictions have put upward pressure on prices here and have contributed to the current “oligopoly” (the “Big Four” have around 80 percent of the market). It speculates that additional foreign competition in the U.S. air travel market could lower prices by as much as 21 percent. Finally, the aforementioned NERA paper estimates that partial cabotage liberalization would generate not only substantial fare reductions, but also more jobs in the sector (i.e., “a net increase in total aviation industry employment, as the jobs created in order to meet the demand generated by lower fares outweigh the job losses as a result of productivity improvements”).

Lower fares, more routes/capacity, more jobs—and no federal subsidies or brute force needed. Huzzah!

Summing it All Up

Relaxing U.S. air cabotage restrictions wouldn’t solve every problem dogging the U.S. airline industry and imperiling your summer travel plans. Labor issues and related regulations, for example, still loom large—especially for legacy carriers. But Europe’s deregulatory experiences—and our own—show that nixing cabotage restrictions would not only put additional downward pressure on fares but also likely improve route coverage and maybe even customer service. (Hey, don’t laugh: The legacy carriers’ moves to improve service during the pandemic show that they do respond when the bottom line is threatened.)

As for reasons to reject liberalization, they sound a lot like the Jones Act excuses and are similarly weak: The national security stuff is mostly bogus; as noted already, liberalization would most likely increase employment in the industry, and changes to immigration policy and unnecessary federal licensing requirements could help address any new labor demand; and U.S. airlines receive plenty of subsidies themselves, rendering hollow various concerns about “unfair” foreign competition (and foreign subsidies would, of course, be quite good for American consumers, regardless!). Instead, as Matt Yglesias explained in Slate years ago, cabotage restrictions are really just another case of good ol’ fashioned protectionism: “More competition would be bad for the established U.S. airlines and their employees” (plus, as he notes, the politically powerful union that represents them). That opposition helped kill a useful U.S.-EU trade agreement negotiated during the Obama years, and it’s making our lives worse today.

Given all the challenges facing American air travel and travelers in our post-covid world, it’s far past time we told those political impediments to… take off.

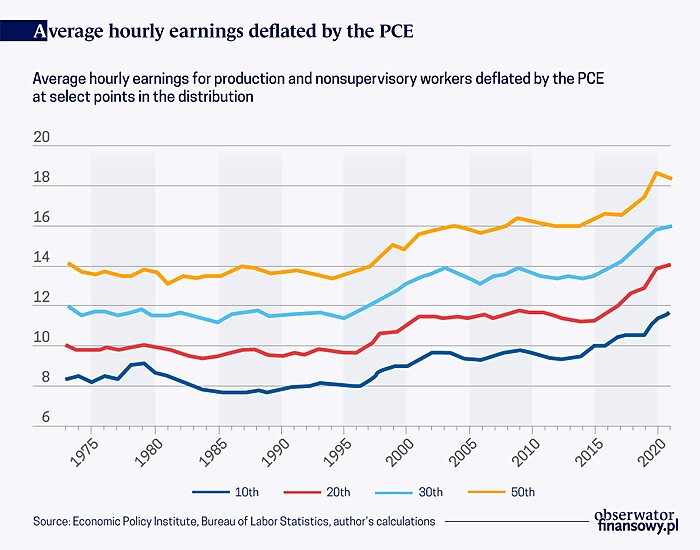

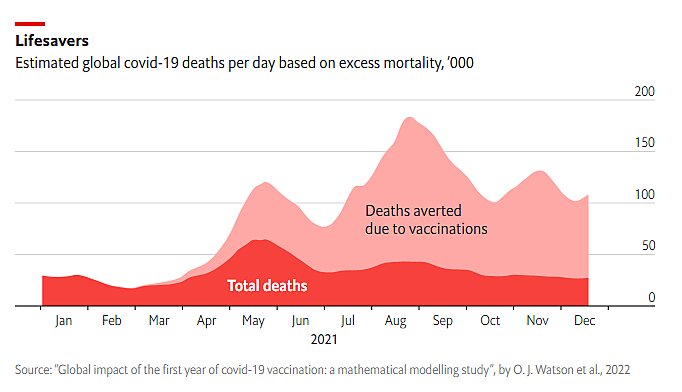

Chart of the Week

The Links

Protectionism undermines economic resilience

What might actually lower gas prices

A labor shortage silver lining

Research: windfall profits tax decreased US crude oil production

Nominal GDP overheating in US, not EU

A big win for school choice in Arizona

Dems cool to Biden’s gas tax holiday push

U.S. faces shortage of oil pipe (which is—of course!—heavily tariffed)

Populist brainworms destroy possible Dem-Business alliance

Ethanol prices skyrocket following Biden expansion

”Banned unless expressly approved by multiple layers of government,” Raleigh edition