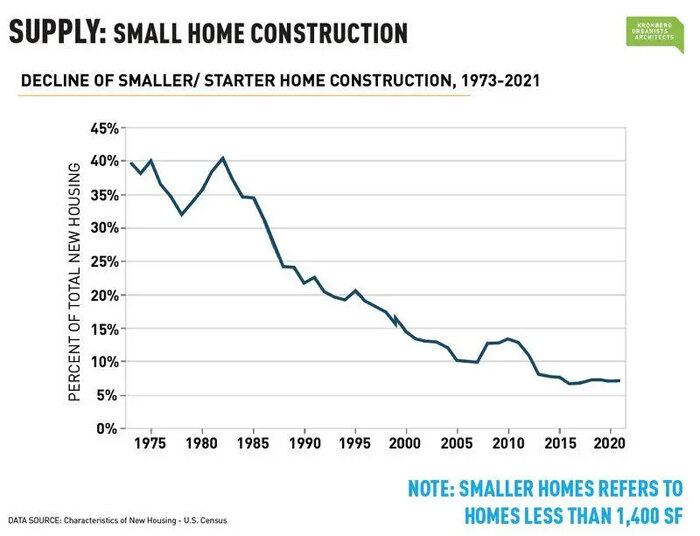

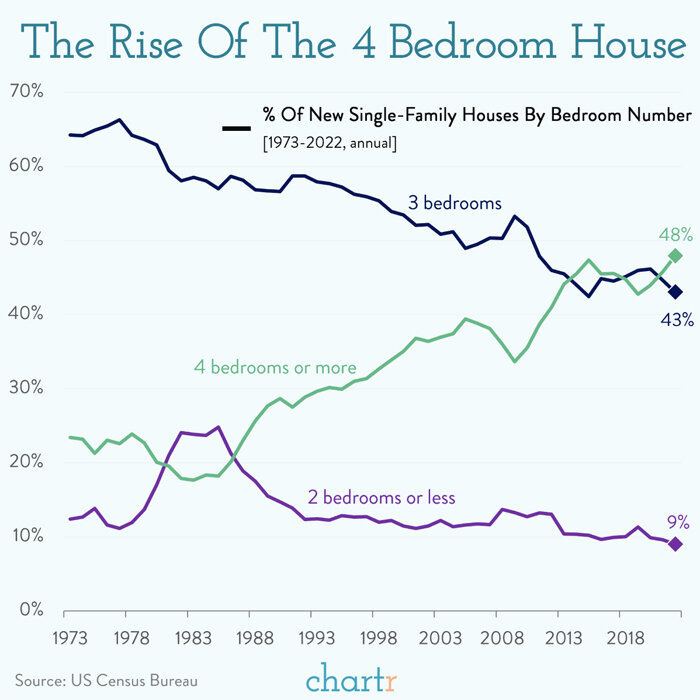

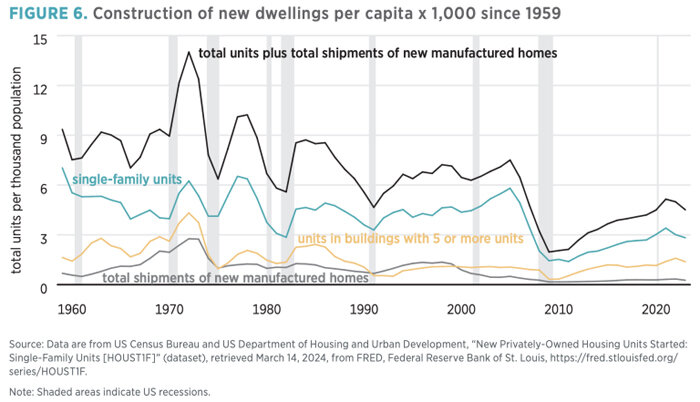

Among the most messed-up aspects of the messed-up U.S. housing market is the relative disappearance of the American starter home. Once ubiquitous in towns across the country, smaller, more affordable homes aren’t being built like they once were—a trend stretching back decades. Here are a couple charts in this regard:

Some of this trend simply reflects American consumers’ preferences for larger homes—maybe to have a guest room, home office, man cave, she shed, or whatever trendy term we’re using today to just say “extra space.” Yet several government policies are also driving builders away from starter homes, operating on both the supply and demand sides of the market.

Policies Inflating Builders’ Costs (Supply Side)

We’ve covered the supply side stuff a lot in recent years, so I’ll just briefly recap what’s going on there. As I wrote for USA Today earlier this year (and have discussed here at Capitolism repeatedly), land across the country—but especially in high-growth areas—is made artificially expensive by “local zoning and land use regulations that dictate home sizes, yard sizes, parking and more, while giving politicians and residents an effective veto over anything that might deviate from these strict terms.” These policies create, in effect, a “zoning tax” on residential land of potentially hundreds of thousands of dollars—dollars paid by companies that build new housing.

Other government policies add to their homebuilding bill (emphasis mine):

Federal tariffs on construction materials, hard caps on immigration, high local permitting and building fees, and property and other taxes increase American homebuilders’ costs and thus discourage the construction of smaller starter homes with lower profit margins. National housing subsidies and city building codes preference traditional, “stick-built” homes over less expensive manufactured housing. And the U.S. government’s ownership of large amounts of land, particularly in the West, makes it unavailable for development and acts as hard barrier to the expansion of neighboring localities

As indicated in my quote above and detailed by the New York Times in 2022, these regulatory price-increasers impede the construction of starter homes in the United States because they make it exceedingly difficult for American builders to keep their all-in costs—plus a reasonable profit—below a small home’s expected sales price in the local market at issue:

“When we started out 20 or so years ago, we could buy a lot for $10,000-$15,000, and we could build a home for under $100,000,” said Mary Lawler, the head of Avenue Community Development Corporation in Houston, a nonprofit developer. “It was a totally different world than we are in today.”

In Portland, Ore., a lot may cost $100,000. Permits add $40,000-$50,000. Removing a fir tree 36 inches in diameter costs another $16,000 in fees.

“You’ve basically regulated me out of anything remotely on the affordable side,” said Justin Wood, the owner of Fish Construction NW.

In Savannah, Ga., Jerry Konter began building three-bed, two-bath, 1,350-square-foot homes in 1977 for $36,500. But he moved upmarket as costs and design mandates pushed him there.

“It’s not that I don’t want to build entry-level homes,” said Mr. Konter, the chairman of the National Association of Home Builders. “It’s that I can’t produce one that I can make a profit on and sell to that potential purchaser.”

Other reports show the same problems. In Minnesota, for example, it’s effectively impossible for developers to build a home in the $150,000 to $250,000 price range because of not just land and construction costs but eye-popping regulatory fees: “One third of the total package price, with the land, is in the regulatory costs,” one builder noted, including “your wetland fees, your park dedication fees, your permit costs,” and more. Thus, a house in Corcoran, Minnesota, that costs $182,000 to build will have an all-in cost of $372,000, including $56,000 in administrative costs alone! Throw in a modest profit margin, and you’re well out of “starter” range in the area. The same goes for estimates from Michigan and New Jersey.

In each case, the numbers change but the math is the same: Because home prices generally track square footage and construction costs aren’t linear—i.e., the cost of adding another room to a house is relatively low because land, fees, and other fixed costs don’t change with home size—it’s safer and easier for builders to hit their profit targets by focusing on bigger, more expensive houses. Thus, for example, a Minnesota builder can hypothetically spend $372,000 on a 2,000 square foot home that might sell for $400,000 on the open market, or he can spend $450,000 on a 4,000 square foot home that sells for twice that amount (meaning much better and less risky profit margins).

I asked a local North Carolina builder to walk me through the math in a few towns outside Raleigh, and he effectively confirmed the stories above. In particular, his company tries to build “attainable homes”—defined as homes people can buy with roughly 30 percent of a county’s AMI (area median income). In many of the places he serves (with AMIs around $60,000), this means buyers in the starter-home price range will generally be able to afford a 1,400 square foot home priced at $240,000 (or $171 per square foot). However, he faces the following costs for such a home that make hitting the target price exceedingly difficult:

- A finished lot needs to be around $40,000 (or about $30/square foot), but “there are no lots in that price range because of local state and planning regulations and fees.” Most “affordable” lots in the area are more like $65,000 (or $45/square foot).

- Construction cost is “the highest it has ever been” at about $90/square foot for even the biggest builders. That translates to about $126,000 for our starter home, meaning the builder is already at $191,000 in costs for a home that he might safely price and sell for $240,000.

- Add in selling commissions, closing costs, concessions, taxes, fees, overhead, etc., and the builder might end up seeing just $9,000 in net profit on our $240,000 starter home. If the builder borrowed money to build the home, it’ll cost him another $3,000, and if the home stays on the market for a while, he could end up losing money altogether.

Thus, he concludes, these ever-increasing costs mean there’s just “not enough money in starter homes to warrant the risk” of taking a loss, especially with interest rates where they are today. And supply-side policies deserve much of the blame.

Policies Crimping Eligible Homebuyers (Demand Side)

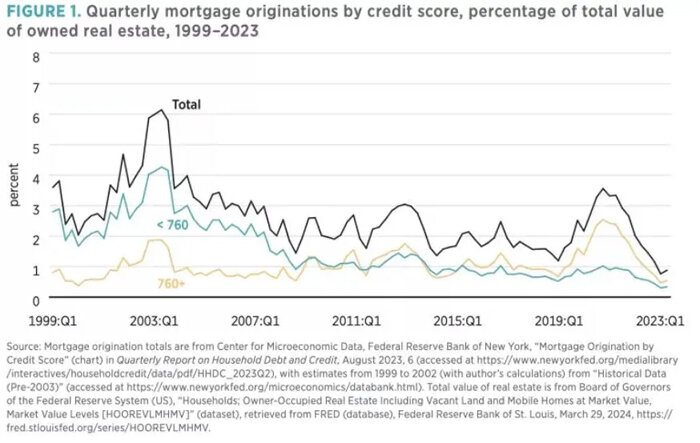

The other, lesser-discussed policies stunting the U.S. starter home market come from the demand (consumer) side. First, the Mercatus Center’s Kevin Erdmann shows that onerous government regulation of private mortgage markets severely limited the number of lower-income Americans who could qualify. In particular, “federal officials both informally and formally turned the screws on Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac so that conventional lending to homebuyers which had been served by Fannie and Freddie for decades, since well before the subprime boom, was cut off.” Thus, he shows that “the average credit score on approved mortgages jumped by 40 points between late 2007 and late 2009,” and “more than half of the mortgage market below credit scores of 760 was cut off”:

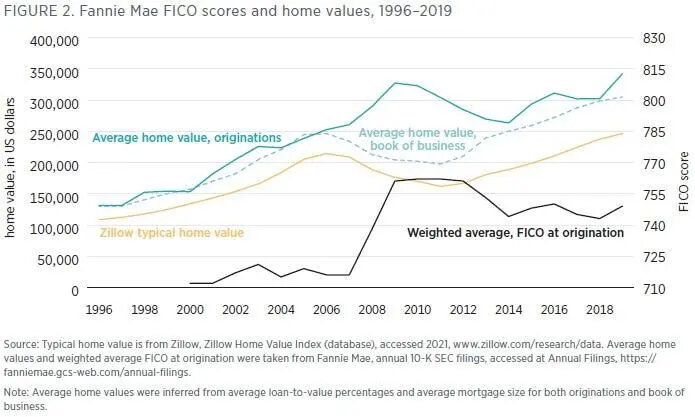

At the same time, the average price of homes that received a new Fannie Mae mortgage went from around $250,000 before 2009 to about $327,000 that year:

Elsewhere, Erdmann elaborates on how the tightening of FHA lending terms crippled the U.S. starter home market (emphasis mine):

When mortgage access dried up for families seeking to find affordable homes, the prices of those homes collapsed. Builders couldn’t profitably sell new homes because existing homes were cheaper than new homes….

Figure 6 shows the number of manufactured homes, apartments, and single-family homes produced each year since 1959. The half million affordable units whose potential owners no longer were able to borrow has permanently been removed from our housing production capacity.

Before the Great Recession, about five single-family homes and one apartment were produced for every 1,000 Americans each year. But construction of apartments has been limited by onerous restrictions, and construction of new single-family, owner-occupied homes has been limited by demand (sales to families that can get mortgages are maxed out). Since it is limited to families that can get a mortgage, new single-family home sales now top out at two to three units per 1,000 Americans. …

Builders haven’t been producing affordable homes below $200,000 because the prices of existing homes have been too low. The drop in prices was due to suppressed mortgage activity, not because of a decline in the demand for housing. For this reason, rents in affordable neighborhoods didn’t fall after 2008—only home prices did.

Now the North Carolina builder’s “risk” comment makes more sense: There are lots of starter home customers in theory, but—thanks to onerous mortgage regulation after the Great Recession—there are far fewer of them in practice today. Without strong and consistent real-world demand for starter homes, building them is just too big a risk for many builders in many places, especially in places with higher land, construction, and administrative costs. The numbers just don’t pencil out.

Whether Fannie and Freddie should exist at all is an open, but separate, question. (They shouldn’t.) But as long as these entities do exist, this is a problem that should be fixed.

The other demand side problem is with the banks offering home loans. As Winston-Salem State University economics professor Craig J. Richardson recently explained, the 2010 Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act (aka “Dodd-Frank”) did two big things to hurt the market for starter home mortgages. First, it raised banks’ overhead costs and pushed small banks— i.e., the ones most likely to provide starter home mortgages—out of the market (emphasis mine):

Dodd–Frank imposed more overhead costs on each specific loan. An extensive and intensive income-verification process was now a requirement, adding to the expense of processing a loan. This made smaller loans even less profitable relative to larger loans because the verification process ate up more of the bank’s profit. In addition, lenders were forced to provide special training to all loan officers at their branches, following specific Dodd–Frank rules, further squeezing overall profits.

Community banks were hit particularly hard by these rising fixed costs because they issued a larger share of small-dollar mortgages and had less financial capital to absorb these blows. A 2020 Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation community bank study indicates that the increased regulatory burden from Dodd–Frank was an important factor in the record number of community bank closures. …

The rise in overhead costs from meeting new regulatory changes also accelerated the trend toward consolidation in the banking industry. Between 2006 and 2021, the number of commercial banks fell by 43 percent, from 7,402 to 4,236, while the share of total banking assets held by small banks (defined as having less than $10 billion in assets) fell from 27.5 percent in 2000 to 18.0 percent in 2014. The small community banks that were most likely to issue small mortgages and smaller home equity lines are finding it difficult, if not impossible, to be profitable.[block]

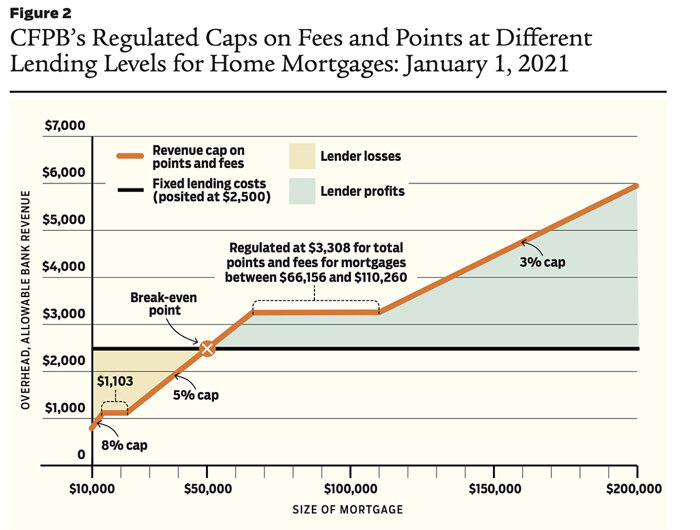

Second, the law capped the amount of money banks could make on certain home mortgages:

Dodd–Frank’s new rules clamped down on the revenue that banks could earn for originating loans. Ostensibly, Dodd–Frank sought to address the hidden closing costs and other fees that often caught consumers by surprise in the run-up to the financial crisis. The Qualified Mortgage Rule, implemented by the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB), capped the fees and points that lenders can charge for processing a loan on a sliding scale based on the size of a loan. The caps were meant to prevent “exploitative behavior” by banks charging “unfair” or “greedy” prices for executing loans. However, these price caps created problems that are familiar to anyone who has taken a freshman economics class: they caused an inevitable shortage of mortgage credit.

As a result of these two things, banks’ higher overhead costs now routinely exceeded their break-even points for smaller, cheaper homes. In other words, Dodd-Frank has made issuing small mortgages unprofitable for most commercial banks. This problem is shown in Figure 2 below: The horizontal line at $2,500 represents a hypothetical bank’s fixed, internal overhead costs to process a loan of any size, and the red line represents the revenue the bank can legally make on a mortgage. At point X, the revenue line meets the overhead cost line, meaning that anything to the left of the X generates revenues below the bank’s overhead cost and thus “represents losses for the bank.” In a free market, Richardson adds, a bank would increase its closing costs to cover the fixed overhead costs of processing a loan, but since the bank legally can’t do that, it just doesn’t issue the loan at all.

Thus, Dodd-Frank has “obstructed access to home ownership for many at the bottom of the economic ladder,” and this, in turn, has a similar effect on the supply of new starter homes to the one Erdmann described above: “[W]hen Dodd–Frank banking regulations were imposed on banks, this led to an evaporation of potential buyers who previously could have used mortgage and home improvement credit, leading to a drop in demand for these homes.” With less starter home demand, you have lower prices of existing homes and tighter margins (and more risk of losses) for potential builders, pushing them away from the starter home market and toward bigger, safer, and more profitable houses.

Summing It All Up

Local, state, and federal policies increase homebuilders’ costs above a point at which they can reasonably expect even a modest return on the construction of smaller, cheaper homes in many parts of the country. And federal mortgage and banking regulations have significantly reduced the number of potential American homebuyers in the same segment of the market. Put them together, and it’s easy to see that the dearth of starter homes in America today isn’t some sort of damning failure of the free market (or whatever) but multiple failures of multiple governments across the country.

Charts of the Week